Alan Seeger

American war poet and soldier (1888–1916) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

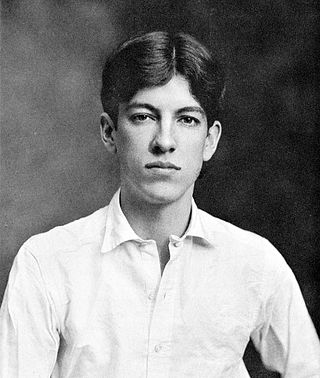

Alan Seeger (22 June 1888 – 4 July 1916) was an American war poet who fought and died in World War I during the Battle of the Somme, serving in the French Foreign Legion. Seeger was the brother of Elizabeth Seeger, a children's author and educator, and Charles Seeger, a noted American pacifist and musicologist; he was also the uncle of folk musicians Pete Seeger, Peggy Seeger, and Mike Seeger. He is lauded for the poem "I Have a Rendezvous with Death", a favorite of President John F. Kennedy.[1] A statue representing him is on the monument in the Place des États-Unis, Paris, honoring those American citizens who volunteered to fight for the Third French Republic while their country was still neutral and lost their lives during the war. Seeger is sometimes called the "American Rupert Brooke".[2]

Alan Seeger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 June 1888 New York City, New York |

| Died | 4 July 1916 (aged 28) Belloy-en-Santerre, France |

| Cause of death | Died of wounds |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | France |

| Service | French Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1916 |

| Battles / wars | First World War |

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Seeger was born on June 22, 1888, in New York City.[3] According to Alan's nephew, folk singer Pete Seeger, the Seeger family was "enormously Christian, in the Puritan, Calvinist New England tradition."[4] In practice, though, Alan's immediate family lived within the precepts of the evolution of Calvinism into Unitarianism. His parents were married in the Unitarian Church,[5] and Alan and his brother, Charles, were educated in schools based in Unitarianism: the Horace Mann School in Manhattan, the Hackley School in Tarrytown and Harvard College. The family traced their American heritage to the 18th century. A paternal ancestor, Karl Ludwig Seeger, a doctor from Württemberg, Germany, emigrated to America after the American Revolution and married into the old New England family of Parsons in the 1780s.[6]

Alan's father, Charles Seeger, Sr., was influential in the late 19th century development of Mexico and its relationship with the United States through publishing, infrastructure development, and sugar refining. Alan's first years included a brief time spent in Mexico City before the family returned to live on Staten Island, where his sister Elizabeth (Elsie) was born. Elizabeth became an author and New York City educator. Alan's older brother Charles Seeger, Jr. became a noted musicologist, and the father of the American folk singers Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger, and Peggy Seeger.

Seeger's family was well-to-do, and Charles, Sr. was a figure in international commerce throughout his life. In 1898, the family moved from Staten Island to an apartment near Central Park. In 1900, Charles' business interests took the family back to Mexico City where he took a role in the development of the city's transportation infrastructure and become a merchant of electric automobiles.

Young Alan's short time in Mexico provides material for his later, and longest, poem, "The Deserted Garden".[7] In 1902, Seeger left Mexico City with his brother to attend Hackley School in Tarrytown, New York, after which he attended Harvard University.[3] His Harvard class of 1910 included the poet T. S. Eliot.[8] During Seeger's first few years at Harvard, he was primarily fixated on intellectual pursuits and did not have a significant social life. However, as an upperclassman and editor at The Harvard Monthly, he found a group of friends that shared his aesthete sensibilities, including Walter Lippmann and John Reed.[9] With Lippmann, he founded a Socialist club at Harvard to protest anti-labor policies at the university.[8]

Upon graduation from Harvard, Seeger returned to Manhattan to live primarily in a boardinghouse at 61 Washington Square South that came to be known variously as The Alan Seeger House or House of Genius. Run by the Swiss émigré Catherine Branchard, its residents at one time or another included Theodore Dreiser, Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, Robert Moses, Sydney Porter (O. Henry), John Reed, and other figures of American literature.[5] While in Greenwich Village, he attended soirées at the Petitpas Restaurant, where the artist and sage John Butler Yeats, father of the poet William Butler Yeats, held court.[10] After two years, Seeger left Greenwich Village to move to Paris, where he lived in the Latin Quarter and continued to pursue a bohemian lifestyle.[3]

Military service and writing

Seeger was living on Rue du Sommerard in Paris in 1914, when war was declared between France and Germany. He quickly volunteered to fight as a member of the Foreign Legion in the French Army, stating that he was motivated by his love for France and his belief in the Allies.[11] For Seeger, fighting for the Allies was a moral imperative; in his poem "A Message to America," he spoke out against what he saw as America's moral failure to join the war.[8]

During the two years he fought in the French Foreign Legion, Seeger wrote regular dispatches to the New York Sun, and the essay "As A Soldier Thinks of War" for Walter Lippman's fledgling magazine, The New Republic posited that though war was lamentable and the cause of death, this one was inevitable and necessary. For the most part, his poetry of that time was not well known and would not become so until after his death.[5] His work was heavily influenced by the Romantic school, and by the precepts of chivalry and medieval ethos of the knight. As the war progressed, the theme of death grew stronger in his poetry, culminating in what became his most famous poem, "I Have a Rendezvous with Death."[12]

Death and aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

In the winter of 1915, he developed bronchitis and spent several months recovering before he returned to the battlefront.[13] He was killed in action in 1916, during a French attack against the Imperial German Army at Belloy-en-Santerre, during the Battle of the Somme.[14] His fellow legionnaire, Rif Baer, later described his last moments: "His tall silhouette stood out on the green of the cornfield. He was the tallest man in his section. His head erect, and pride in his eye, I saw him running forward, with bayonet fixed. Soon he disappeared and that was the last time I saw my friend."[9][13] After being mortally wounded in no man's land, Seeger cheered on the passing soldiers of the Legion before he finally died from his injuries.[15] According to one account, knowing he was mortally wounded, he killed himself with a gunshot to the head.[16]

Seeger had been falsely reported dead after the Battle of Champagne in October 1915, in which he had fought.[9] The news of his actual death was met with public mourning in both America and France.[17] After the USA entered World War I, Poems, a posthumously published collection of Seeger's war poetry, sold out six editions in a year.[12] The poet Edwin Arlington Robinson, who had described Seeger as "the Hedonist" after meeting him in 1911, suggested that it might be best that he had died in the war, "for I don’t believe that he would ever have come anywhere near to fitting himself into this interesting but sometimes unfittable world."[18]

It is assumed, and officially stated, that Seeger's bones rest with other dead of the Belloy-en-Santerre battle in ossuary No. 1 of the French National Cemetery in Lihons.[19] After his death, Seeger's parents donated a bell to a local church and planted trees in his honor. Both of their contributions to Belloy-en-Santerre were destroyed during World War II,[17] though the remains of the bell were combined with other metals into a new church bell, and one of the apple trees was believed to be still alive behind the village hall at Belloy en Santerre as of 2016.

Poetry

Summarize

Perspective

Seeger's poetry was published by Charles Scribner's Sons in December 1916 with a 46-page introduction by William Archer. Poems, a collection of his works, was relatively unsuccessful, due, according to Eric Homberger, to its lofty idealism and language, qualities out of fashion in the early decades of the 20th century.[20]

Poems was reviewed in The Egoist, where T.S. Eliot stated:

Seeger was serious about his work and spent pains over it. The work is well done, and so much out of date as to be almost a positive quality. It is high-flown, heavily decorated and solemn, but its solemnity is thorough going, not a mere literary formality. Alan Seeger, as one who knew him can attest, lived his whole life on this plane, with impeccable poetic dignity; everything about him was in keeping.[21][20]

His most famous poem, "I Have a Rendezvous with Death", is believed to have been completed during a winter 1916 bivouac at Crevecoeur,[5] and was published posthumously.[14][22] It begins,

- I have a rendezvous with Death

- At some disputed barricade,

- When Spring comes back with rustling shade

- And apple-blossoms fill the air—

- I have a rendezvous with Death

- When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

A recurrent theme in both his poetic works and his personal writings was his desire for his life to end gloriously at an early age.

According to the New York Times, "President Kennedy had loved the poem so much that his wife Jacqueline memorized it at his request."[1] The poem continues to resonate today and was quoted by the President of France, Emmanuel Macron, in a speech to the U.S. Congress in April 2018.[23]

Memorials and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

In 1919, Seeger's father Charles, while living in Paris, determined to devote royalties received for Poems and for a subsequent Letters and Diary, published in 1917, to the founding of what became the American Library in Paris. Charles became its first board chairman.

On 4 July 1923, the President of the French Council of State, Raymond Poincaré, dedicated a monument in the Place des États-Unis to the Americans who had volunteered to fight in World War I in the service of France. The monument, in the form of a bronze statue on a plinth, executed by Jean Boucher, had been financed through a public subscription.[24]

Boucher had used a photograph of Seeger as his inspiration, and Seeger's name can be found, among those of 23 others who had fallen in the ranks of the Foreign Legion in the French Army on the back of the plinth. Also, on either side of the base of the statue, are two excerpts from Seeger's "Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers Fallen for France", a poem written shortly before his death on 4 July 1916. Seeger intended that his words should be read in Paris on 30 May of that year, at an observance of the American holiday, Decoration Day (later known as Memorial Day):

They did not pursue worldly rewards; they wanted nothing more than to live without regret, brothers pledged to the honor implicit in living one's own life and dying one's own death. Hail, brothers! Goodbye to you, the exalted dead! To you, we owe two debts of gratitude forever: the glory of having died for France, and the homage due to you in our memories.

On July 3 and 4, 2016, the centennial of Seeger's death was memorialized in two separate ceremonies at the monument at Place Des États-Unis, and at Belloy-en-Santerre, where 500 people from the US, France, Germany and Spain gathered to commemorate his role in the liberation of the village, as well as those of German poet Reinhard Sorge and Catalan poet Camil Campanya, also associated with the battle.

In 1921, Alan Seeger Natural Area, in central Pennsylvania, was named by the folklorist and conservationist Colonel Henry Shoemaker in honor of Seeger. In the same year, the "Alan Seeger Tree" was planted and dedicated in Washington Square Park before the Branchard boarding house in an event led by poet/historian Walter Adolphe Roberts. The tree disappeared at some point probably in the mid-century.[5] The liberty ship SS Alan Seeger, a tanker, was launched by the California Shipbuilding Corp 5 October 1943, during World War II.[25]

Author Chris Dickon wrote what is widely considered the definitive biography of Seeger in 2017, A Rendezvous with Death: Alan Seeger in Poetry, at War. Dickon spoke about Seeger and his work at the American Library, Paris, shortly after the publication of his book.[26]

Also in 2017, the oratorio Alan Seeger: Instrument of Destiny by American composer Patrick Zimmerli was premiered at the Cathédrale Saint Louis des Invalides in Paris, followed by an American premier at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York in 2019.On 9 November 2018, an opinion commentary by Aaron Schnoor in The Wall Street Journal honored the poetry of World War I, including Seeger's poem "I Have a Rendezvous With Death".[27]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.