Loading AI tools

Moroccan former War on Terror detainee From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

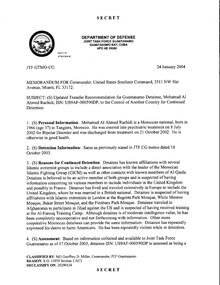

Ahmed Rashidi (also known as Ahmed Errachidi) is a citizen of Morocco who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba.[2] Rashidi's Guantanamo ISN was 590. The Department of Defense reports that he was born on March 17, 1966, in Tangier, Morocco.

| Ahmed Errachidi | |

|---|---|

Mohamad Al Ahmed Rachidi's Guantanamo detainee assessment | |

| Born | March 16, 1966[1] Tangier, Morocco |

| Arrested | 2002 Bannu, Pakistan |

| Released | 2007 Morocco |

| Citizenship | Morocco |

| Detained at | Guantanamo |

| ISN | 590 |

| Charge(s) | no charge (extrajudicial detention) |

| Status | repatriated |

| Occupation | chef |

Rashidi's lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith, wrote an article in The Guardian on June 14, 2006, commenting on the American reaction to the three Guantanamo detainees who committed suicide on June 10, 2006.[3] Smith comments focused on what he characterized as the camp authority's leaders plans to prevent future suicides by increasing their brutality. In particular he commented on Colonel Michael Bumgarner's announcement that he would send a five-man riot squad in to conduct a Forcible Cell Entry to forcibly strip Rashidi of his brown coveralls.[4] Smith said that Rashidi had already had mental and emotional problems prior to being sent to the camp.

Rashidi did not attend his Combatant Status Review Tribunal.

Rashidi had a habeas corpus petition submitted on his behalf. As a consequence a dossier of documents from his CSR Tribunal was published. Rashishi's dossier was 19 pages long.

His status was reviewed by Tribunal panel 13, on October 7, 2004.

His Personal Representative notes from the meeting where the Summary of Evidence memo was read to Rashidi stated:

Detainee was extremely verbally belligerent towards both myself and translator. Detainee was making accusations of the US Government throughout the interview. During the time, when the Unclassified Summary of Evidence was read to him, he became extremely agitated and verbally belligerent. He started physicalIy, moving in his chair and making movements towards the table between him and myself/translator. I terminated the interview at that time.

Detainees whose Combatant Status Review Tribunal labeled them "enemy combatants" were scheduled for annual Administrative Review Board hearings. These hearings were designed to assess the threat a detainee might pose if released or transferred, and whether there were other factors that warranted his continued detention.[5]

Documents from Rashidi's CSR Tribunal indicated he had been confirmed as an "enemy combatant", and was going to start having annual Administrative Review Board hearings. However, records the Department of Defense published in September 2007 showed that no annual reviews were convened for him. There is no record any Summary of Evidence memos were prepared for annual review boards.[6][7][8] Prior to his repatriation Rashidi was described as a captive who had been cleared for release.[9] But there is no record that an Administrative Review Board drafted a decision memos recommending his release or transfer.[10][11]

On July 14, 2006 The Boston Globe reported on investigations they made to test the credibility of the allegations against Guantanamo detainees.[12] Rashidi was one of the detainees who they profiled.[13]

The Globe reported that Rashidi was alleged to have been attended the al Farouq training camp in Afghanistan.[13] According to the Globe:

the US military has accused Ahmed Errachidi... of 'receiving training at the Al Farooq training camp in July 2001, to include weapons training, war tactics, and bomb making.' according to a summary of evidence for his initial hearing provided to the Globe by his lawyers at Reprieve, a British legal-services organization.

But Chris Chang, an investigator for Reprieve, uncovered pay stubs showing that Errachidi had been a chef in two London restaurants, the Westbury and the Archduke, in July 2001. Chang's office provided copies of the pay stubs to the Globe.

On August 7, 2008 The Washington Post'' reported that the Guantanamo guards defied their orders to discontinue the illegal practice of arbitrarily moving captives multiples times a day to deprive them of sleep.[14] The report stated that Ahmed Rashidi was routinely having six-hour interrogations in the middle of the night, followed by a series of cell relocations. Guards called this practice the "frequent flyer program".

Lieutenant-Colonel David Cooper, of the Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants, wrote Rashidi's lawyers on February 22, 2007.[9] He wrote that Rashidi and another man, Ahmed Belbacha, had: "...been approved to leave Guantanamo, after diplomatic arrangements for their departure had been made."

British officials continued to decline to make efforts on behalf of the Guantanamo captives who were British residents, but not British citizens.[9]

A close friend back in the United Kingdom, Abderrazzak Sakim, and Clive Stafford Smith, told the Islington Gazette, his local paper, that they were concerned that if he were repatriated to Morocco, he would be promptly subjected to abusive detention in a Moroccan prison.[15] The paper reports that Rashidi spent three years in solitary confinement, and has been subjected to beatings and pepper spraying.

The paper quotes Emily Thornberry, his local Member of Parliament:[15]

Guantanamo Bay is an affront to international law. While Ahmed Errachidi has been in Guantanamo he has been subject to appalling abuse and has suffered at least one severe mental breakdown. He should never have been in Guantanamo Bay and he certainly shouldn't be there for a moment longer.

It's completely unacceptable that Ahmed should be left in limbo like this, while the international community wrings its hands about the detainees the US no longer wants.

Surely he has more than sufficient compassionate grounds to be allowed to come back to Britain. Ahmed must be released immediately and I have written to George Bush to tell him so.

The Department of Defense reported, on April 26, 2007, that two further captives had been repatriated, one to Morocco, one to Afghanistan.[16][17] Initially the DoD declined to release the two men's names. But it soon became known that Ahmed Rashidi was the Moroccan man, that he hadn't been released to a third country.[18]

Rashidi was not charged, but he was detained by Moroccan authorities, when he was repatriated.[18][19]

Rashidi was released on Thursday, May 3, 2007.[20] Reuters reports that Rashidi had traveled to Pakistan, where he was captured in late 2001, to try to raise funds for a heart operation for his young son.[21] Reuters reports that Rashidi described hearing his Pakistani captors negotiate, with US officials, the size of the bounty they would receive for turning him over.

In March 2009 Rashidi was interviewed, by email from his home in Tangiers, by Toronto Star reporter Michelle Shephard, the author of Guantanamo's Child, a book about Guantanamo captive Omar Khadr, who was a minor when he was captured and sent to Guantanamo.[22] According to Shephard, Rashidi said their fellow captives felt particularly sorry for Khadr, because he was so young, and because they could tell when it was his turn to be subjected to brutal interrogation techniques.

I felt so desperate every time I saw him. I wanted to say, "Sorry I can't help you." It was well known if some detainee is going through torture courses and I remember there was a time when everyone was talking about Omar having his turn.

In early 2013 Errachidi published a memoir, "The General: The ordinary man who challenged Guantanamo".[23] According to Marco Giannangeli, who reviewed the book for the Daily Express, Errachidi believed that he continued to be targeted for aggressive interrogation, years after his total innocence had been established, because the US military used Guantanamo as a school to train new interrogators. Giannangeli reported that Errachidi described how the Guantanamo guards were taken to "ground zero"—the site of the ruins of the World Trade Center, so that they were "already consumed by hatred with the conviction we were the worst of the worst". Giannangeli reported how Errachidi found being one of the limited number of captives who spoke English singled him out for special attention from the guards and interrogators, and forced him to serve as an unofficial leader within the captive community. Guards nicknamed Errachidi "The General".

The book was co-written by Gillian Slovo, the South African writer and filmmaker.[24] Paddy McGuffin, writing in The Morning Star Online, called the book a "damning indictment of the policy of extra-judicial detention as well as a fascinating account of an innocent man's fight to prevent himself being buried alive under the full weight of US officialdom."

In May, at the height of the 2013 hunger strike Rachedi was interviewed by the New American Media.[25] Rachidi said he had engaged in many hunger strikes, and described what being on a hunger strike is like. He disputed the assertions from US officials that the hunger strike was simply intended to win the captives a return to less harsh conditions. Rather, Rachidi asserted the hunger strike was ultimately the captives way of fighting for justice. Rachidi said that, since the captives were older and more frail than they were during previous hunger strikes, he feared captives would die during this strike.

Rachidi said that he has not been allowed to get a new passport, even for attending the launch of his memoir.[25]

On January 29, 2021, the New York Review of Books published an open letter from Rachidi, and six other individuals who were formerly held in Guantanamo, to newly inaugurated President Biden, appealing to him to close the detention camp.[26]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.