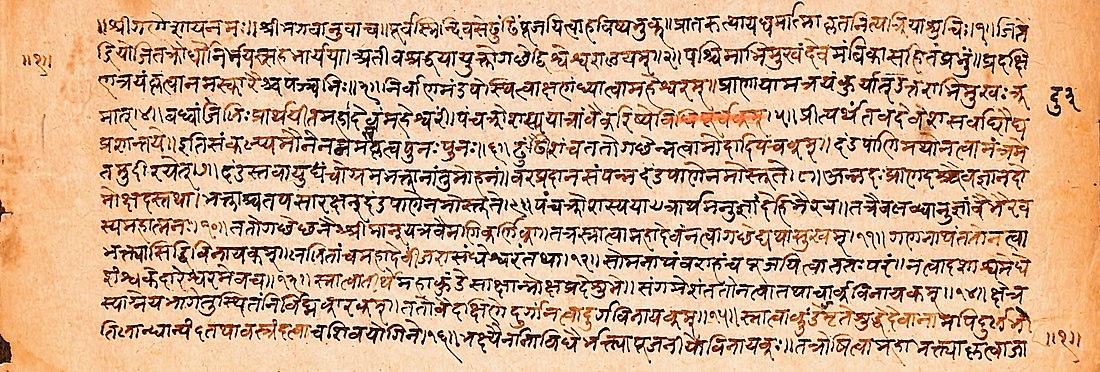

Agni Purana

Sanskrit Hindu text, one of the eighteen major Puranas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Agni Purana, (Sanskrit: अग्नि पुराण, Agni Purāṇa) is a Sanskrit text and one of the eighteen major Puranas of Hinduism.[1] The text is variously classified as a Purana related to Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism, but also considered as a text that covers them all impartially without leaning towards a particular theology.[1][2]

The text exists in numerous versions, some very different from others.[3] The published manuscripts are divided into 382 or 383 chapters, containing between 12,000 and 15,000 verses.[3][4] The chapters of the text were likely composed in different centuries, with earliest version probably after the 7th-century,[5][6] but before the 11th century because the early 11th-century Persian scholar Al-Biruni acknowledged its existence in his memoir on India.[7] The youngest layer of the text in the Agni Purana may be from the 17th century.[7]

The Agni Purana is a medieval era encyclopedia that covers a diverse range of topics, and its "382 or 383 chapters actually deal with anything and everything", remark scholars such as Moriz Winternitz and Ludo Rocher.[8][9] Its encyclopedic secular style led some 19th-century Indologists such as Horace Hayman Wilson to question if it even qualifies as what is assumed to be a Purana.[10][11] The range of topics covered by this text include cosmology, mythology, genealogy, politics, education system, iconography, taxation theories, organization of army, theories on proper causes for war, martial arts,[5] diplomacy, local laws, building public projects, water distribution methods, trees and plants, medicine,[12] design and architecture,[13][14] gemology, grammar, metrics, poetry, food and agriculture,[15] rituals, geography and travel guide to Mithila (Bihar and neighboring states), cultural history, and numerous other topics.[4]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Charity

The man who gratuitously teaches another,

a craft or a trade or settles upon him a property,

whereby he earns a livelihood,

acquires infinite merit.

—Agni Purana 211.63, Translator: MN Dutt[16]

Tradition has it that its title is named after Agni because it was originally recited by Agni to the sage Vasishta when the latter wanted to learn about the Brahman, and Vasishta later recited it to Vyasa – the sage who compiled all the Vedas, Puranas and many other historic texts.[3][17] Vyasa recited it to Suta, who then recited to the rishis in Naimisharanya.[18] The Skanda Purana and Matsya Purana assert that the Agni Purana describes Isana-kalpa as described by god Agni, but the surviving manuscripts make no mention of Isana-kalpa.[19] Similarly, medieval Hindu texts cite verses that they claim are from Agni Purana, but these verses do not exist in current editions of the text.[19] These inconsistencies, considered together, have led scholars such as Rajendra Hazra to conclude that the extant manuscripts are different from the text Skanda and Matsya Puranas are referring to.[19]

The earliest core of the text is likely a post 7th-century composition, and a version existed by the 11th century.[7][20][21] The chapters that discuss grammar and lexicography may be an addition in the 12th century, while the chapters on metrics likely predate 950 CE because Pingala-sutras text by the 10th-century scholar Halayudha cites this text.[22] The section on poetics is likely a post-900 CE composition,[23] while its summary on Tantra is likely to be a composition between 800 and 1100 CE.[24]

The Agni Purana exists in many versions and it exemplifies the complex chronology of the Puranic genre of Indian literature that has survived into modern times. The number of chapters, number of verses and the specific content vary across Agni Purana manuscripts.[3][4] Dimmitt and van Buitenen state that each of the Puranas is encyclopedic in style, and it is difficult to ascertain when, where, why and by whom these were written:[25]

As they exist today, the Puranas are a stratified literature. Each titled work consists of material that has grown by numerous accretions in successive historical eras. Thus, no Puran has a single date of composition. (...) it is as if they were libraries to which new volumes have been continuously added, not necessarily at the end of the shelf, but randomly.

— Cornelia Dimmitt and J.A.B. van Buitenen, Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas[25]

Structure

The published manuscripts are divided into 382 or 383 chapters, and ranging between 12,000 and 15,000 verses.[3][4] Many subjects it covers are in specific chapters, but states Rocher, these "succeed one another without the slightest connection or transition".[26] In other cases, such as its discussion of iconography, the verses are found in many sections of the Agni Purana.[9]

Editions and translations

The first printed edition of the text was edited by Rajendralal Mitra in the 1870s (Calcutta : Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1870–1879, 3 volumes; Bibliotheca Indica, 65, 1–3). The entire text extends to slightly below one million characters.[citation needed]

An English translation was published in two volumes by Manmatha Nath Dutt in 1903–04. There are several versions published by different companies.[citation needed]

Contents

Summarize

Perspective

The extant manuscripts are encyclopedic. The first chapter of the text declares its scope to be such.[27] Some subjects covered by the text include:[28]

| Subject | Chapters | Illustrative content | Reference |

| Book summary | 21-70 | Pancaratra texts, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Pingala-Sutras, Amarakosha, etc. | [26][27] |

| Regional geography | 114-116 | Mithila (now Bihar), rivers, forests, towns, culture | [26][27] |

| Medicine | 279-286, 370 | Ayurveda, herbs, nutrition | [26][29] |

| Buddhist incantations | 123-149 | Summary of the Buddhist text Yuddhajayarnava, mantras of Trailokyavijaya | [26][30][31] |

| Politics | 218-231 | Structure of a state, education and duties of a king and key ministers, organization of army, theory of just war, ambassadors to other kingdoms, system of administration, civil and criminal law, taxation, local administration and court system | [26][32][33] |

| Agriculture, planning | 239, 247, 282, 292 | Fortification, trees and parks, water reservoirs | [26][34][35] |

| Martial arts, weapons | 249-252 | 32 types of martial arts, making and maintaining weapons | [36] |

| Cow | 310 | Holiness of cow, breeding and taking care of cows | [37] |

| Hindu temple, monastery | 25, 39-45, 55-67, 99-101 | Design, layout, construction, architecture | [38] |

| Metrics, poetics, art of writing | 328-347 | Summary of different schools on poetics, music, art of poetry, Alamkara, Chandas, Rasa, Riti, language, rhetoric | [24][39][40] |

| Yoga, moksha | 372-381 | Eight limbs of yoga, ethics, meditation, samadhi, soul, non-dualism (Advaita), summary of Bhagavad Gita | [22][41][42][43] |

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.