374th Strategic Missile Squadron

Military unit of the United States Air Force From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

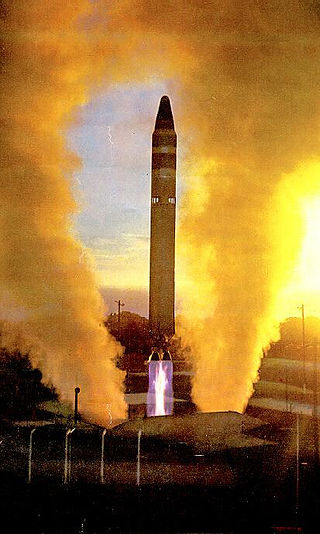

The 374th Strategic Missile Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit, last assigned to the 308th Strategic Missile Wing at Little Rock Air Force Base, Arkansas. The squadron was equipped with the LGM-25C Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), with a mission of nuclear deterrence. It was inactivated as part of the phaseout of the Titan II ICBM on 15 August 1986. The squadron was responsible for Launch Complex 374–7, site of the 1980 explosion of a Titan II ICBM in Damascus, Arkansas.

| 374th Strategic Missile Squadron | |

|---|---|

LGM-25C Titan II Test Launch at Vandenberg AFB, California | |

| Active | 1942–1946; 1947–1951; 1951–1961; 1962–1986 |

| Country | |

| Branch | United States Air Force |

| Type | Squadron |

| Role | Intercontinental ballistic missile |

| Engagements | China Burma India Theater[1] |

| Decorations | Distinguished Unit Citation (3x) Air Force Outstanding Unit Award[1] |

| Insignia | |

| 374th Strategic Missile Squadron emblem[a] |  |

| Patch with 374th Bombardment Squadron emblem[b][1] |  |

The squadron was first activated in April 1942 as the 374th Bombardment Squadron. After training in the United States, the squadron deployed to China in early 1943. It engaged in combat, primarily in China and Southeast Asia until June 1945, when it assumed a mainly transport role. It was awarded two Distinguished Unit Citations for its operations in China and its attacks on Japanese shipping. At the end of 1945 it returned to the United States for inactivation.

The squadron was redesignated the 374th Reconnaissance Squadron and activated in California in 1947. It was inactivated in 1949. It returned to its bombardment designation in 1951 and operated Boeing B-47 Stratojets for Strategic Air Command. In 1959 it moved as part of a test of a "super wing" concept, but was not operational until in inactivated in 1961.

History

Summarize

Perspective

World War II

Initial organization and training

The squadron was activated at Gowen Field, Idaho on 15 April 1942 as the 374th Bombardment Squadron, one of the four original squadrons of the 308th Bombardment Group.[2][3] As the squadron was forming and beginning its training in Consolidated B-24 Liberators, at Alamogordo Army Air Field, New Mexico in August 1942, almost all its personnel were transferred to the 330th Bombardment Group.[4]

The following month, a fresh cadre taken from the 39th Bombardment Group joined the group. In addition to its own training activities, at the beginning of October, the unit was briefly designated as an Operational Training Unit[4] The squadron began its movement to the China Burma India Theater in January 1943.[1] The air echelon ferried its Liberators across the Atlantic and Africa, leaving from Morrison Field, while the ground echelon moved by ship across the Pacific.[3][4]

Combat operations

In late March 1943, the squadron arrived at Chengkung Airfield, China. In order to prepare for and sustain combat operations in China, the squadron had to conduct numerous flights over the Hump transporting gasoline, lubricants, ordnance, spare parts and the other items it needed. The 374th supported Chinese ground forces and attacked airfields, coal yards, docks, oil refineries and fuel dumps in French Indochina. It attacked shipping, mined rivers and ports and bombed maintenance shops and docks at Rangoon, Burma and attacked Japanese shipping in the East China Sea, Formosa Straits, South China Sea and Gulf of Tonkin. On 21 August 1943, the squadron conducted an unescorted bombing attack on docks and warehouses at Hankow, China, pressing its attack despite heavy flak and fighter opposition. For this mission it was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC). Its operations interdicting Japanese shipping in 1944 and 1945 earned it a second (DUC).[3]

On 26 October 1944, Major Horace S. Carswell, the squadron's operations officer, attacked a Japanese convoy in the South China Sea, meeting with heavy antiaircraft fire, badly damaging his plane. Because of the damage, once he was over land, he ordered the crew to bail out. One crewmember could not bail out because his parachute had been shredded by the enemy fire. Major Carswell remained at the controls to attempt a crash landing, but his Liberator struck a mountain and crashed in the attempt. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.[3] Carswell Air Force Base, Texas was named in his honor.[5]

The squadron moved to Rupsi Airfield, Assam, India in June 1945. Its mission again was primarily air transport as it ferried gasoline and supplies from there back into China. The unit sailed for the United States in October 1945, and it was inactivated at the Port of Embarkation on 6 January 1946.[1][3]

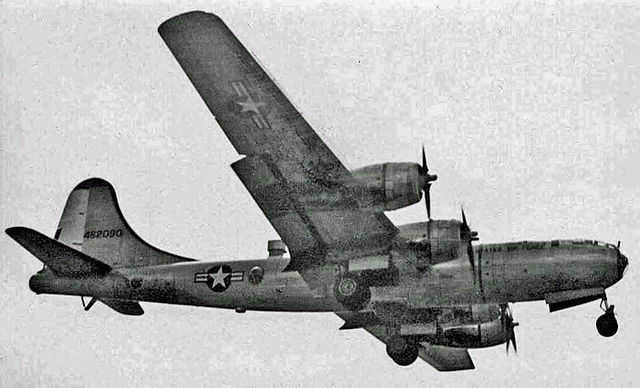

Weather reconnaissance

The squadron was reactivated at Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Field, California on 15 October 1947 as the 374th Reconnaissance Squadron, an Air Weather Service weather reconnaissance squadron,[1] assuming the personnel and Boeing B-29 Superfortresses of the 55th Reconnaissance Squadron, which was simultaneously inactivated.[6] The squadron performed weather reconnaissance, deploying elements to England and Saudi Arabia. In October 1949, the squadron moved to McClellan Air Force Base, California, where it was inactivated in February 1951[1] and its personnel and equipment transferred to the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron.[6]

Strategic Air Command

Bomber operations

It was reactivated a few months later in October with new B-47E Stratojet swept-wing medium bombers, which were capable of flying at high subsonic speeds and primarily designed for penetrating the airspace of the Soviet Union.

By the late 1950s, the B-47 was considered to be reaching obsolescence, and was being phased out of SAC's strategic arsenal. B-47s began the transition to AMARC (also known as the boneyard) at Davis-Monthan in July 1959 and the squadron became non-operational. It was inactivated on 25 June 1961.

Intercontinental ballistic missile squadron

The squadron was reactivated and redesignated as the 374th Strategic Missile Squadron, a SAC LGM-25C Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile missile squadron in 1962. It operated nine Titan II underground silos, construction of which began in 1960; the first (374–9), being operationally ready on 28 Oct 1963. The nine missile silos controlled by the 374th Strategic Missile Squadron remained on alert for over 20 years during the Cold War. The 1980 Damascus Titan missile explosion is a 'Broken Arrow' incident occurred at site 374–7 on 19 September 1980 which killed one airman and injured twenty-one personnel in the immediate vicinity (see below).

In October 1981, President Ronald Reagan announced that as part of the strategic modernization program, the Titan II systems were to be retired by 1 October 1987. Inactivation of the sites began on 17 March 1985 with 374-8 being the first; the last was on 15 Aug 1986 involving 374–1, 374–4 and 374–2. The squadron was inactivated the same day.

After removal from service, the silos had reusable equipment removed by Air Force personnel, and contractors retrieved salvageable metals before destroying the silos with explosives and filling them in. Access to the vacated control centers was blocked off. Missile sites were later sold off to private ownership after demilitarization. Today the remains of the sites are still visible through aerial imagery, in various states of use or dereliction.

Launch Complex 374-7 incident

On 18 September 1980 at Titan II Launch Complex 374–7, a 308th Missile Maintenance Squadron airman was adding pressure to the second stage oxidizer tank. During an incorrect application of a 9-pound socket wrench to the pressure cap, the airman accidentally dropped the socket, which fell down the silo, glanced off the thrust mount and punctured the pressurized first stage fuel tank containing aerozine 50.

Aerozine 50 is hypergolic with the Titan II's oxidizer, nitrogen tetroxide; i.e., they spontaneously ignite on contact with each other. Eventually, the crew evacuated the launch control center as military and civilian response teams arrived to tackle the hazardous situation. Early in the morning of 19 September, a two-man investigation team entered the silo. Because their vapor detectors indicated an explosive atmosphere, the two were ordered to evacuate.

At about 0300 hours, a tremendous explosion rocked the area. One possible trigger for the explosion was the collapse of the now-empty first stage fuel tank, allowing the rest of the missile (including the full oxidizer tank of the first stage) to fall and rupture, allowing the oxidizer to contact the fuel already in the silo. The initial explosion catapulted the 740-ton silo door away from the silo and ejected the second stage and warhead. Once clear of the silo, the second stage exploded. The warhead safety devices performed as designed and it did not explode. Twenty-one personnel in the immediate vicinity of the blast were injured. One member of the two-man silo reconnaissance team who had just emerged from the portal sustained fatal injuries.

At daybreak, the Air Force retrieved the warhead and took it to Little Rock AFB. During the recovery, the Missile Wing Commander received strong support from other military units as well as Federal, state, and local officials. Arkansas's governor, Bill Clinton, played an important role in overseeing the proper deployment of state emergency resources.

The wing received some of its greatest accolades in the wake of the disaster. Perhaps realizing the public confidence had suffered a blow, wing personnel made a stronger effort to reach out to local communities. This effort won Air Force recognition in 1983, when the wing became the first missile wing ever to win the General Bruce K. Holloway humanitarian service trophy for the year 1982. The unit also earned the Omaha trophy for 1982, recognizing it as the best in SAC.

Lineage

Summarize

Perspective

- Constituted as the 374th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy) on 28 January 1942

- Activated on 15 April 1942.

- Redesignated 374th Bombardment Squadron, Heavy on 20 August 1943

- Inactivated on 6 January 1946

- Redesignated 374th Reconnaissance Squadron (Very Long Range, Weather) on 16 September 1947.

- Activated on 15 October 1947

- Inactivated on 21 February 1951

- Redesignated 374th Bombardment Squadron, Medium on 4 October 1951

- Activated on 10 October 1951.

- Discontinued and inactivated on 25 June 1961

- Redesignated 374th Strategic Missile Squadron (ICBM-Titan) and activated 1 Sep 1962[7]

- Inactivated on 15 Aug 1986

Assignments

- 308th Bombardment Group, 15 April 1942 – 6 January 1946

- 7th Weather Group (later 2107th Air Weather Group), 15 October 1947 – 21 February 1951

- 308th Bombardment Group, 10 October 1951 (attached to 21st Air Division until 17 April 1952)

- 308th Bombardment Wing, 16 June 1952 – 25 June 1961 (not operational after 15 July 1959)

- 308th Strategic Missile Wing, 1 September 1962 – 15 August 1986[7]

Stations

|

|

Aircraft and missiles

- Douglas B-18 Bolo, 1942

- Consolidated B-24 Liberator, 1942–1945

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress, 1947–1951, 1951–1952

- Boeing WB-29 Superfortress, 1947–1951

- Boeing RB-29 Superfortress, 1947–1951

- Douglas C-47 Skytrain, 1947–1951

- Boeing B-47 Stratojet, 1953–1959

- LGM-25C Titan II, 1962–1986[7]

- The squadron operated nine missile sites:

- 374-1 (23 Dec 1963 – 15 Aug 1985), 1.1 mi ENE of Blackwell, Arkansas 35°13′36″N 092°49′18″W

- 374-2 (19 Dec 1963 – 15 Aug 1986), 2.0 mi NNE of Plummerville, AR 35°11′19″N 092°37′50″W

- 374-3 (19 Dec 1963 – 5 Aug 1986), 3.9 mi ENE of Hattieville, AR 35°18′41″N 092°43′25″W

- 374-4 (28 Dec 1963 – 15 Aug 1986), 1.4 mi NNE of Springfield, AR 35°17′15″N 092°32′50″W

- 374-5 (26 Dec 1963 – 19 May 1986), 3.3 mi ESE of Wooster, AR 35°10′04″N 092°23′33″W

- 374-6 (18 Dec 1963 – 25 Jun 1986), 3.8 mi SW of Guy, AR 35°17′30″N 092°23′12″W

- 374-7 (18 Dec 1963 – 21 Sep 1980)*, 3.3 mi NNE of Damascus, AR 35°24′50″N 092°23′50″W

- 374-8 (20 Dec 1963 – 17 Mar 1985), 4.3 mi SSW of Quitman, AR 35°19′45″N 092°14′59″W

- 374-9 (28 Oct 1963 – 3 Oct 1985), 2.5 mi SSW of Pearson, AR 35°24′34″N 092°08′58″W

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.