2020 Nobel Prize in Literature

Award From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

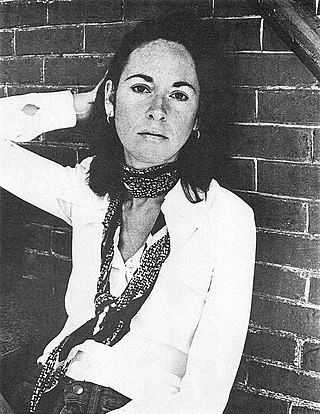

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the American poet Louise Glück (1943–2023) who the Swedish Academy members praised "for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal." The winner was announced on October 8, 2020, by Mats Malm, permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy.[1] She is the 13th Nobel laureate in Literature from the United States after 2016 laureate Bob Dylan and 1993 laureate Toni Morrison.[2]

| 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature | |

|---|---|

| Louise Glück | |

"for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal." | |

| Date |

|

| Location | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Presented by | Swedish Academy |

| First award | 1901 |

| Website | Official website |

Laureate

Louise Glück was an American poet and essayist known for her autobiographical poems of intense emotions and drawing mythological and natural imageries in understanding personal life and experiences. Among the recurring themes in her collections are about childhood, family life, relationships and death. In addition to classical mythology, the rich English-language poetry tradition is her primary literary source of inspiration. Her language is characterized by clarity and precision and is free of poetic formalities. A United States Poet Laureate, she has garnered numerous literary prizes such as the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and the Bollingen Prize. Among her celebrated poem collections are The Triumph of Achilles (1985), The Wild Iris (1992), Averno (2006), and Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014).[3]

Reactions

Summarize

Perspective

The Red Poppy

The great thing

is not having

a mind. Feelings:

oh, I have those; they

govern me. I have

a lord in heaven

called the sun, and open

for him, showing him

the fire of my own heart, fire

like his presence.

What could such glory be

if not a heart? Oh my brothers and sisters,

were you like me once, long ago,

before you were human? Did you

permit yourselves

to open once, who would never

open again? Because in truth

I am speaking now

the way you do. I speak

because I am shattered.

The Wild Iris, 1992

Personal reactions

In a short interview conducted by Adam Smith, Chief Scientific Officer of Nobel Media, in the early hours of Thursday morning, Glück was asked what the award would mean to her. She responded saying:

"I have no idea. My first thought was 'I won’t have any friends' because most of my friends are writers. But then I thought 'no, that won't happen'. It's too new, you know … I don't know really what it means. And I don't know whether... I mean it's a great honour, and then of course there are recipients I don't admire, but then I think of the ones that I do, and some very recent. I think, practically, I wanted to buy another house, a house in Vermont – I have a condo in Cambridge – and I thought 'well, I can buy a house now'. But mostly I am concerned for the preservation of daily life with people I love."[3]

Following the announcement, Glück found herself in an uncomfortable, "nightmarish" situation due to the endless phone calls that "hadn't stopped ringing since 7:00 am" and where journalists lining up outside her residence in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[4] Asked by New York Times as to how did she feel once she absorbed that her win was real, she said:

"Completely flabbergasted that they would choose a white American lyric poet. It doesn't make sense. Now my street is covered with journalists. People keep telling me how humble I am. I'm not humble. But I thought, I come from a country that is not thought fondly of now, and I'm white, and we’ve had all the prizes. So it seemed to be extremely unlikely that I would ever have this particular event to deal with in my life.[4]

International reactions

Favourites to win the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature included Canadian poet Anne Carson, Antigua-American writer Jamaica Kincaid, Chinese novelist Yan Lianke, Russian writer Lyudmila Ulitskaya and Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.[3]

The chair of the Nobel prize committee, Anders Olsson hailed Glück's "candid and uncompromising" voice, which is full of humour and biting wit. Her 12 collections of poetry, including her most recent Faithful and Virtuous Night, the Pulitzer-winning The Wild Iris, and the Averno, are characterised by a striving for clarity", he added, comparing her to Emily Dickinson with "her severity and unwillingness to accept simple tenets of faith".[3][5]

Fellow poet Claudia Rankine told The Guardian that she was so pleased that it was conferred to her. "Something good had to happen!" Rankine said. "She is a tremendous poet, a great mentor, and a wonderful friend. I couldn't be happier. We are in a bleak moment in this country, and as we poets continue to imagine our way forward, Louise has spent a lifetime showing us how to make language both mean something and hold everything."[3][5] Deccan Herald described her "an underwhelming choice for the Nobel Prize" because of the confronting reality that there were other writers who deserved it more. Furthermore, they expressed: "Though Glück is a much-admired poet, she is not very well-known."[6]

Jonathan Galassi, president of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, told Reuters he was certain the Nobel prize would bring Gluck "to many, many new reader." He described her as "one of the rare contemporary poets whose work has the gift of speaking directly to readers through her great and subtle art."[7] Yale president Peter Salovey congratulated, saying: "Yale celebrates a poet of the interior life, whose unsparing explorations of the self and its place in the world in volume after volume have created poems of beauty and revelation. We also honor a galvanizing teacher who has given herself unstintingly to students, who revere her."[8]

Nobel lecture

Summarize

Perspective

In her Nobel lecture, which was delivered in writing, she highlighted her early engagement with poetry by William Blake, Stephen Foster and Emily Dickinson in discussing the relationship between poets, readers, and the wider public, also minimally citing T. S. Eliot and William Shakespeare.[9] She concluded her lecture, saying:

"I believe that in awarding me this prize, the Swedish Academy is choosing to honor the intimate, private voice, which public utterance can sometimes augment or extend, but never replace."[9]

'Minstrel Show' controversy

Immediately after her lecture was made available, numerous literary critics and fellow poets described it as "disastrously bad" and "refines racism."[10][11][12] Her invocation of Blake's "The Little Black Boy" (written by a white abolitionist in the voice of a Black boy who was enslaved) and Stephen Foster's "Swanee River" (a song by a writer whose work was a staple of minstrel shows) was questioned by many on Twitter.[12] Many noted that Glück, even if she meant to make a timely point about racism, might have used the words of an actual person of color, and not the caricature of a Black person as imagined by a white man.[11][12]

Matt Sandler, author of The Black Romantic Revolution: Abolitionist Poets at the End of Slavery, commented on the Nobel lecture, saying:

"Glück's undelivered Nobel Prize lecture stirred up a controversy so familiar as to seem rote, almost generic. An accomplished white artist proffers the refinement of their racism as craft, then awaits their due in attention, attack, defense, and more laurels... However carefully constructed her interior castle may be, Glück could hardly have failed to notice the resurgence of abolitionism over the past decade, especially in this past summer’s massive protests of police violence... Glück’s anecdote rang way off key, even for white readers who might in other moments have welcomed her indulgence. To mix her terms with those of the radical present, the racially maldistributed character of contemporary privacy is simply too obvious."[11]

American poet Mary Karr for whom Glück served as a thesis adviser expressed disappointment, saying: "At this point in history, Louise Glück – my grad thesis advisor [and] a poet I deeply admire – wrote a minstrel show Nobel speech. In 1789, Blake's 'Black Boy' might have passed as 'abolitionist', but it came out of a shoe-polished white face. Wake TF up."[12] Poet Li Yin Alvarado reacted in Twitter, saying: "elevating a poem — however abolitionist in intent — that is rooted in upholding white supremacy, understandably, I think, turns off readers for whom fighting against said supremacy is a not some literary or intellectual exercise, but an actual matter of survival."[12]

Activist and author Faylita Hicks expressed: "There was no reason to speak about the "little Black boy" conjured up by the mind of Blake. Any other poem could have stood in. It is violence when one chooses, still, to recommend and elevate a white man's caricature over any other Black man or women's genius."[12] American writer Alissa Quart compared Glück with the controversial 2019 Nobel laureate Peter Handke through a Twitter post: "Louise Gluck follows Peter Handke as really wrong Nobel prize winners in literature. Why not Susan Howe, Anne Carson, Erica Hunt, Nathaniel Mackey, [or] Jorie Graham? Gluck and the vacuity of apolitical poetry of status quo leads directly to minstrelsy. No coincidence."[12]

Award ceremony

Summarize

Perspective

Prize presentation

During the award ceremony held on December 10, 2020, Prof. Anders Olsson delivered the following statement about Glück:[13]

"Louise Glück's poems are written in retrospect. Childhood and taut relationships with parents and siblings are motifs that have never loosened their grip. Glück has produced twelve collections of poetry and a couple of volumes of essays on poetry, all marked by a drive for clarity. Nobody is more adamant than she against self-illusions. The autobiographical material is crucial, but Glück is scarcely a confessional poet. The "truth" to be revealed detours through imagination and vicarious voices, like the painter's. In several of her books, Glück speaks through mythical figures such as Dido, Persephone or Eurydice."

"[She] is a writer not only of contradictions and austere reflection. She is also a poet of renewal, with few coequals. Even if her poetry is written in retrospect, and seems bound to the apple tree as it was seen once in childhood, one of her keywords is change. She teaches us that the moment of renewal is also the arrival of words. Her inner driving force is a spiritual hunger and an exceptional reverence for the possibilities of poetry. The leap of renewal can employ the seemingly plain diction of thoughtful parables, but also comedy and biting wit. And when Louise Glück in her later work confronts the inevitable end, there is a remarkable grace and lightness in her touch. It is a note that lingers and can carry us readers forward as well."

Due to the restrictions by the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual Nobel banquet was postponed, however, Glück still received her medal, diploma and monetary prize from the Swedish Academy at her residence in New York City.[14]

Nobel Committee

The Swedish Academy's Nobel Committee for the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature were the following members:

| Committee Members | |||||

| Seat No. | Picture | Name | Elected | Position | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 |  |

Anders Olsson (b. 1949) |

2008 | committee chair | literary critic, literary historian |

| 11 |  |

Mats Malm (b. 1964) |

2018 | associate member permanent secretary |

translator, literary historian, editor |

| 8 |  |

Jesper Svenbro (b. 1944) |

2006 | member | poet, classical philologist |

| 12 |  |

Per Wästberg (b. 1933) |

1997 | member | novelist, journalist, poet, essayist |

| External Members | |||||

|

Mikaela Blomqvist (b. 1987) |

2018 | member | literary critic, theatre critic | |

| Rebecka Kärde (b. 1991) |

member | literary critic, translator | |||

| Henrik Peterson (b. 1973) |

member | translator, literary critic, publisher | |||

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.