Loading AI tools

Official compilation of U.S. federal statutes From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The United States Code (formally the Code of Laws of the United States of America)[1] is the official codification of the general and permanent federal statutes of the United States.[2] It contains 53 titles, which are organized into numbered sections.[3][4]

Obverse of the Great Seal | |

| Editor | Office of the Law Revision Counsel |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Government Publishing Office |

| OCLC | 2368380 |

| Text | Code of Laws of the United States of America at Wikisource |

The U.S. Code is published by the U.S. House of Representatives' Office of the Law Revision Counsel. New editions are published every six years, with cumulative supplements issued each year.[2][5][6] The official version of these laws appears in the United States Statutes at Large, a chronological, uncodified compilation.

The official text of an Act of Congress is that of the "enrolled bill" (traditionally printed on parchment) presented to the President for his signature or disapproval. Upon enactment of a law, the original bill is delivered to the Office of the Federal Register (OFR) within the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).[7] After authorization from the OFR,[8] copies are distributed as "slip laws" (as unbound, individually paginated pamphlets) by the Government Publishing Office (GPO).[9] The OFR assembles annual volumes of the enacted laws and publishes them as the United States Statutes at Large. By law, the text of the Statutes at Large is "legal evidence" of the laws enacted by Congress.[10] Slip laws are also competent evidence.[11]

The Statutes at Large, however, is not a convenient tool for legal research. It is arranged strictly in chronological order; statutes addressing related topics may be scattered across many volumes, and are not consolidated with later amendments.[12] Statutes often repeal or amend earlier laws, and extensive cross-referencing is required to determine what laws are in force at any given time.[2]

The United States Code is the result of an effort to make finding relevant and effective statutes simpler by reorganizing them by subject matter, and eliminating expired and amended sections. The Code is maintained by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel (LRC) of the U.S. House of Representatives.[2] The LRC determines which statutes in the United States Statutes at Large should be codified, and which existing statutes are affected by amendments or repeals, or have simply expired by their own terms. The LRC updates the Code accordingly.

Because of this codification approach, a single named statute (like the Taft–Hartley Act or the Embargo Act) may or may not appear in a single place in the Code. Often, complex legislation bundles a series of provisions together as a means of addressing a social or governmental problem; those provisions often fall in different logical areas of the Code. For example, an Act providing relief for family farms might affect items in Title 7 (Agriculture), Title 26 (Tax), and Title 43 (Public Lands). When the Act is codified, its various provisions might well be placed in different parts of those various Titles. Traces of this process are generally found in the Notes accompanying the "lead section" associated with the popular name, and in cross-reference tables that identify Code sections corresponding to particular Acts of Congress.

Usually, the individual sections of a statute are incorporated into the Code exactly as enacted; however, sometimes editorial changes are made by the LRC (for instance, the phrase "the date of enactment of this Act" is replaced by the actual date). Though authorized by statute, these changes do not constitute positive law.[13]

The authority for the material in the United States Code comes from its enactment through the legislative process and not from its presentation in the Code. For example, the United States Code omitted 12 U.S.C. § 92 for decades, apparently because it was thought to have been repealed. In its 1993 ruling in U.S. National Bank of Oregon v. Independent Insurance Agents of America, the Supreme Court ruled that § 92 was still valid law.[14]

A positive law title is a title that is itself a federal statute, that is to say that it is one that has been enacted and codified into law by the United States Congress. The title itself has been enacted. By contrast, a non-positive law title is a title that has not been codified into federal law, and is instead merely an editorial compilation of individually enacted federal statutes. [15]

By law, those titles of the United States Code that have not been enacted into positive law are "prima facie evidence"[16] of the law in effect. The United States Statutes at Large remains the ultimate authority. If a dispute arises as to the accuracy or completeness of the codification of an unenacted title, the courts will turn to the language in the United States Statutes at Large. In case of a conflict between the text of the Statutes at Large and the text of a provision of the United States Code that has not been enacted as positive law, the text of the Statutes at Large takes precedence.

In contrast, if Congress enacts a particular title (or other component) of the Code into positive law, the enactment repeals all of the previous Acts of Congress from which that title of the Code derives; in their place, Congress gives the title of the Code itself the force of law. This process makes that title of the United States Code "legal evidence"[17] of the law in force. Where a title has been enacted into positive law, a court may neither permit nor require proof of the underlying original Acts of Congress.[18]

The distinction between enacted and unenacted titles is largely academic because the Code is nearly always accurate. The United States Code is routinely cited by the Supreme Court and other federal courts without mentioning this theoretical caveat. On a day-to-day basis, very few lawyers cross-reference the Code to the Statutes at Large. Attempting to capitalize on the possibility that the text of the United States Code can differ from the United States Statutes at Large, Bancroft-Whitney for many years published a series of volumes known as United States Code Service (USCS), which used the actual text of the United States Statutes at Large; the series is now published by the Michie Company after Bancroft-Whitney parent Thomson Corporation divested the title as a condition of acquiring West.

Only "general and permanent" laws are codified in the United States Code; the Code does not usually include provisions that apply only to a limited number of people (a private law) or for a limited time, such as most appropriation acts or budget laws, which apply only for a single fiscal year. If these limited provisions are significant, however, they may be printed as "notes" underneath related sections of the Code. The codification is based on the content of the laws, however, not the vehicle by which they are adopted; so, for instance, if an appropriations act contains substantive, permanent provisions (as is sometimes the case), these provisions will be incorporated into the Code even though they were adopted as part of a non-permanent enactment.[19]

Early efforts at codifying the Acts of Congress were undertaken by private publishers; these were useful shortcuts for research purposes, but had no official status. Congress undertook an official codification called the Revised Statutes of the United States approved June 22, 1874, for the laws in effect as of December 1, 1873. Congress re-enacted a corrected version in 1878. The 1874 version of the Revised Statutes were enacted as positive law, but the 1878 version was not and subsequent enactments of Congress were not incorporated into the official code, so that over time researchers once again had to delve through many volumes of the Statutes at Large.

According to the preface to the Code, "From 1897 to 1907 a commission was engaged in an effort to codify the great mass of accumulating legislation. The work of the commission involved an expenditure of over $300,000, but was never carried to completion." Only the Criminal Code of 1909 and the Judicial Code of 1911 were enacted. In the absence of a comprehensive official code, private publishers once again collected the more recent statutes into unofficial codes. The first edition of the United States Code (published as Statutes at Large Volume 44, Part 1) includes cross-reference tables between the USC and two of these unofficial codes, United States Compiled Statutes Annotated by West Publishing Co. and Federal Statutes Annotated by Edward Thompson Co.

During the 1920s, some members of Congress revived the codification project, resulting in the approval of the United States Code by Congress in 1926.[20]

The official version of the Code is published by the LRC (Office of the Law Revision Counsel) as a series of paper volumes. The first edition of the Code was contained in a single bound volume; today, it spans several large volumes. Normally, a new edition of the Code is issued every six years, with annual cumulative supplements identifying the changes made by Congress since the last "main edition" was published.[6]

The official code was last printed in 2018.

Both the LRC and the GPO offer electronic versions of the Code to the public. The LRC electronic version used to be as much as 18 months behind current legislation, but as of 2014 it is one of the most current versions available online. The United States Code is available from the LRC at uscode.house.gov in both HTML and XML bulk formats.[21][22] The "United States Legislative Markup" (USLM) schema of the XML was designed to be consistent with the Akoma Ntoso project (from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs) XML schema,[23] and the OASIS LegalDocML technical committee standard will be based upon Akoma Ntoso.[24]

A number of other online versions are freely available, such as Cornell's Legal Information Institute.

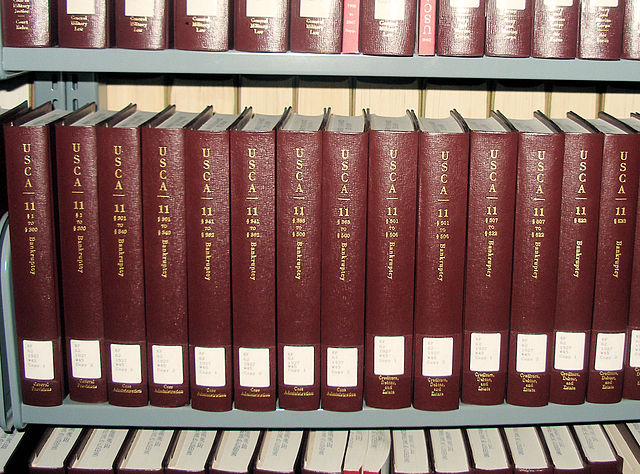

Practicing lawyers who can afford them almost always use an annotated version of the Code from a private company. The two leading annotated versions are the United States Code Annotated, abbreviated as USCA, and the United States Code Service, abbreviated as USCS.[25] The USCA is published by West (part of Thomson Reuters), and USCS is published by LexisNexis (part of Reed Elsevier), which purchased the publication from the Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Co. in 1997 as a result of an antitrust settlement when the parent of Lawyers Co-operative Publishing acquired West.[26] These annotated versions contain notes following each section of the law, which organize and summarize court decisions, law review articles, and other authorities that pertain to the code section, and may also include uncodified provisions that are part of the Public Laws.[25] The publishers of these versions frequently issue supplements (in hard copy format as pocket parts) that contain newly enacted laws, which may not yet have appeared in an official published version of the Code, as well as updated secondary materials such as new court decisions on the subject.[25] When an attorney is viewing an annotated code on an online service, such as Westlaw or LexisNexis, all the citations in the annotations are hyperlinked to the referenced court opinions and other documents.

The Code is divided into 53 titles (listed below), which deal with broad, logically organized areas of legislation. Titles may optionally be divided into subtitles, parts, subparts, chapters, and subchapters. All titles have sections (represented by a §) as their basic coherent units, and sections are numbered sequentially across the entire title without regard to the previously-mentioned divisions of titles. Sections are often divided into (from largest to smallest) subsections, paragraphs, subparagraphs, clauses, subclauses, items, and subitems.[27][28] Congress, by convention, names a particular subdivision of a section according to its largest element. For example, "subsection (c)(3)(B)(iv)" is not a subsection but a clause, namely clause (iv) of subparagraph (B) of paragraph (3) of subsection (c); if the identity of the subsection and paragraph were clear from the context, one would refer to the clause as "subparagraph (B)(iv)".[29]

Not all titles use the same series of subdivisions above the section level, and they may arrange them in different order. For example, in Title 26 (the tax code), the order of subdivision runs: Title – Subtitle – Chapter – Subchapter – Part – Subpart – Section – Subsection – Paragraph – Subparagraph – Clause – Subclause – Item – Subitem.

The "Section" division is the core organizational component of the Code, and the "Title" division is always the largest division of the Code. Which intermediate levels between Title and Section appear, if any, varies from Title to Title. For example, in Title 38 (Veteran's Benefits), the order runs Title – Part – Chapter – Subchapter – Section.

The word "title" in this context is roughly akin to a printed "volume", although many of the larger titles span multiple volumes. Similarly, no particular size or length is associated with other subdivisions; a section might run several pages in print, or just a sentence or two. Some subdivisions within particular titles acquire meaning of their own; for example, it is common for lawyers to refer to a "Chapter 11 bankruptcy" or a "Subchapter S corporation" (often shortened to "S corporation").

In the context of federal statutes, the word "title" has two slightly different meanings. It can refer to the highest subdivision of the Code itself, but it can also refer to the highest subdivision of an Act of Congress which subsequently becomes part of an existing title of the Code.[2] For example, when Americans refer to Title VII, they are usually referring to the seventh title of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[2] That Act is actually codified in Title 42 of the United States Code, not Title 7.[2]

The intermediate subdivisions between title and section are helpful for reading the Code (since Congress uses them to group together related sections), but they are not needed to cite a section in the Code. To cite any particular section, it is enough to know its title and section numbers.[2] According to one legal style manual,[30] a sample citation would be "Privacy Act of 1974, 5 U.S.C. § 552a (2006)", read aloud as "Title five, United States Code, section five fifty-two A" or simply "five USC five fifty-two A".

Some section numbers consist of awkward-sounding combinations of letters, hyphens, and numerals.[31] They are especially prevalent in Title 42.[31] A typical example is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), which is codified in Chapter 21B of Title 42 at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-4.[31] In the case of RFRA, Congress was trying to squeeze a new act into Title 42 between Chapter 21A (ending at 42 U.S.C. § 2000aa-12) and Chapter 22 (beginning at 42 U.S.C. § 2001).[31] The underlying problem is that the original drafters of the Code in 1926 failed to foresee the explosive growth of federal legislation directed to "The Public Health and Welfare" (as Title 42 is literally titled) and did not fashion statutory classifications and section numbering schemes that could readily accommodate such expansion.[31] Title 42 grew in size from 6 chapters and 106 sections in 1926 to over 160 chapters and 7,000 sections as of 1999.[31]

Titles that have been enacted into positive law[32] are indicated by blue shading below with the year of last enactment.

The Office of Law Revision Counsel (LRC) has produced draft text for three additional titles of federal law. The subject matter of these proposed titles exists today in one or several existing titles.

| Title 53[lower-alpha 1] | Small Business[39] |

| Title 55 | Environment |

| Title 56 | Wildlife |

The LRC announced an "editorial reclassification" of the federal laws governing voting and elections that went into effect on September 1, 2014. This reclassification involved moving various laws previously classified in Titles 2 and 42 into a new Title 52, which has not been enacted into positive law.[6]

When sections are repealed, their text is deleted and replaced by a note summarizing what used to be there. This is so that lawyers reading old cases can understand what the cases are talking about. As a result, some portions of the Code consist entirely of empty chapters full of historical notes. For example, Title 8, Chapter 7 is labeled "Exclusion of Chinese".[40] This contains historical notes relating to the Chinese Exclusion Act, which is no longer in effect.

There are conflicting opinions on the number of federal crimes,[41][42] but many have argued that there has been explosive growth and it has become overwhelming.[43][44][45] In 1982, the U.S. Department of Justice could not come up with a number, but estimated 3,000 crimes in the United States Code.[41][42][46] In 1998, the American Bar Association said that it was likely much higher than 3,000, but did not give a specific estimate.[41][42] In 2008, the Heritage Foundation published a report that put the number at a minimum of 4,450.[42] When staff for a task force of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee asked the Congressional Research Service (CRS) to update its 2008 calculation of criminal offenses in the USC in 2013, the CRS responded that they lack the manpower and resources to accomplish the task.[47]

The Code generally contains only those Acts of Congress, or statutes, designated as public laws. The Code itself does not include Executive Orders or other executive-branch documents related to the statutes, or rules promulgated by the courts. However, such related material is sometimes contained in notes to relevant statutory sections or in appendices. The Code does not include statutes designated at enactment as private laws, nor statutes that are considered temporary in nature, such as appropriations. These laws are included in the Statutes at Large for the year of enactment.

Regulations promulgated by executive agencies through the rulemaking process set out in the Administrative Procedure Act are published chronologically in the Federal Register and then codified in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Similarly, state statutes and regulations are often codified into state-specific codes.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.