Loading AI tools

Old English alliterative poem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

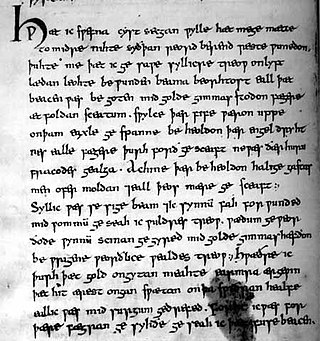

The Dream of the Rood is one of the Christian poems in the corpus of Old English literature and an example of the genre of dream poetry. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative verse. The word Rood is derived from the Old English word rōd 'pole', or more specifically 'crucifix'. Preserved in the tenth-century Vercelli Book, the poem may be as old as the eighth-century Ruthwell Cross, and is considered one of the oldest extant works of Old English literature.

The framing device is the narrator having a dream. In this dream or vision he is speaking to the Cross on which Jesus was crucified. The poem itself is divided up into three separate sections: the first part (lines 1–27), the second part (lines 28–121) and the third part (lines 122–156).[1] In section one, the narrator has a vision of the Cross. Initially when the dreamer sees the Cross, he notes how it is covered with gems. He is aware of how wretched he is compared to how glorious the tree is. However, he comes to see that amidst the beautiful stones it is stained with blood.[2] In section two, the Cross shares its account of Jesus' death. The Crucifixion story is told from the perspective of the Cross. It begins with the enemy coming to cut the tree down and carrying it away. The tree learns that it is not to be the bearer of a criminal, but instead Christ crucified. The Lord and the Cross become one, and they stand together as victors, refusing to fall, taking on insurmountable pain for the sake of mankind. It is not just Christ, but the Cross as well that is pierced with nails. Adelhied L. J. Thieme remarks, "The cross itself is portrayed as his lord's retainer whose most outstanding characteristic is that of unwavering loyalty".[3] The Rood and Christ are one in the portrayal of the Passion—they are both pierced with nails, mocked and tortured. Then, just as with Christ, the Cross is resurrected, and adorned with gold and silver.[4] It is honoured above all trees just as Jesus is honoured above all men. The Cross then charges the visionary to share all that he has seen with others. In section three, the author gives his reflections about this vision. The vision ends, and the man is left with his thoughts. He gives praise to God for what he has seen and is filled with hope for eternal life and his desire to once again be near the glorious Cross.[5]

There are various, alternative readings of the structure of the poem, given the many components of the poem and the lack of clear divisions. Scholars including Faith H. Patten divide the poem into three parts, based on who is speaking: Introductory Section (lines 1–26), Speech of the Cross (lines 28–121), and Closing Section (lines 122–156).[6] Though the most obvious way to divide the poem, this does not take into account thematic unity or differences in tone.[7] Constance B. Hieatt distinguishes between portions of the Cross's speech based on speaker, subject, and verbal parallels, resulting in: Prologue (lines 1–27), Vision I (lines 28–77): history of the Rood, Vision II (lines 78–94): explanation of the Rood's glory, Vision III (lines 95–121): the Rood's message to mankind, and Epilogue (lines 122–156).[8] M. I. Del Mastro suggests the image of concentric circles, similar to a chiasmus, repetitive and reflective of the increased importance in the center: the narrator-dreamer's circle (lines 1–27), the rood's circle (lines 28–38), Christ's circle (lines 39-73a), the rood's circle (lines 73b-121), and the narrator-dreamer's circle (lines 122–156).[9]

The Dream of the Rood survives in the Vercelli Book, so called because the manuscript is now in the Italian city of Vercelli. The Vercelli Book, which is dated to the tenth century, includes twenty-three homilies interspersed with six religious poems: The Dream of the Rood, Andreas, The Fates of the Apostles, Soul and Body, Elene and a poetic, homiletic fragment.

A part of The Dream of the Rood can be found on the eighth-century Ruthwell Cross, which is an 18 feet (5.5 m), free-standing Anglo-Saxon cross that was perhaps intended as a 'conversion tool'.[10] At each side of the vine-tracery are carved runes. There is an excerpt on the cross that was written in runes along with scenes from the Gospels, lives of saints, images of Jesus healing the blind, the Annunciation, and the story of Egypt, as well as Latin antiphons and decorative scroll-work. Although it was torn down after the Scottish Reformation, it was possible to mostly reconstruct it in the nineteenth century.[11] Recent scholarly thinking about the cross tends to see the runes as a later addition to an existing monument with images.

A similar representation of the Cross is also present in Riddle 9 by the eighth-century Anglo-Saxon writer Tatwine. Tatwine's riddle reads:[12]

Now I appear iridescent; my form is shining now. Once, because of the law, I was a spectral terror to all slaves; but now the whole earth joyfully worships and adorns me. Whoever enjoys my fruit will immediately be well, for I was given the power to bring health to the unhealthy. Thus a wise man chooses to keep me on his forehead.

The author of The Dream of the Rood is unknown. Moreover, it is possible that the poem as it stands is the work of multiple authors. The approximate eighth-century date of the Ruthwell Cross indicates the earliest likely date and Northern circulation of some version of The Dream of the Rood.

Nineteenth-century scholars tried to attribute the poem to the few named Old English poets. Daniel H. Haigh argued that the inscription of the Ruthwell Cross must be fragments of a lost poem by Cædmon, portrayed in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People as the first Christian English poet,[13] stating "On this monument, erected about A.D. 665, we have fragments of a religious poem of very high character, and that there was but one man living in England at that time worthy to be named as a religious poet, and that was Caedmon".[14] Likewise, George Stephens contended that the language and structure of The Dream of the Rood indicated a seventh-century date.[15] Supposing that the only Christian poet before Bede was Cædmon, Stephens argued that Cædmon must have composed The Dream of the Rood. Furthermore, he claimed that the Ruthwell Cross includes a runic inscription that can be interpreted as saying "Caedmon made me".[16] These ideas are no longer accepted by scholars.

Likewise, some scholars have tried to attribute The Dream of the Rood to Cynewulf, a named Old English poet who lived around the ninth century.[17] Two of Cynewulf's signed poems are found in the Vercelli Book, the manuscript that contains The Dream of the Rood, among them Elene, which is about Saint Helena's supposed discovery of the cross on which Jesus was crucified.[18] Thus Franz Dietrich argued that the similarities between Cynewulf's Elene and The Dream of the Rood reveal that the two must have been authored by the same individual.[19] Again, however, this attribution is not widely accepted.

In a series of papers, Leonard Neidorf has adduced metrical, lexical, and syntactical evidence in support of a theory of composite authorship for The Dream of the Rood. He maintains that the poem contains contributions from at least two different poets, who had distinct compositional styles.[20][21][22][23]

Like many poems of the Anglo-Saxon period, The Dream of the Rood exhibits many Christian and pre-Christian images, but, in the final analysis, is a Christian piece.[24] Examining the poem as a pre-Christian (or pagan) text is difficult, as the scribes who wrote it down were Christian monks who lived in a time when Christianity was firmly established (at least among the literate and aristocratic population) in early medieval England.[25] The style and form of Old English literary practices can be identified in the poem's use of a complex, echoing structure, allusions, repetition, verbal parallels, ambiguity and wordplay (as in the Riddles), and the language of heroic poetry and elegy.[26]

Some scholars have argued that there is a prevalence of pagan elements within the poem, claiming that the idea of a talking tree is animistic. The belief in the spiritual nature of natural objects, it has been argued, recognises the tree as an object of worship. In Heathen Gods in Old English Literature, Richard North stresses the importance of the sacrifice of the tree in accordance with pagan virtues. He states that "the image of Christ's death was constructed in this poem with reference to an Anglian ideology on the world tree".[27] North suggests that the author of The Dream of the Rood "uses the language of this myth of Ingui in order to present the Passion to his newly Christianized countrymen as a story from their native tradition".[27] Furthermore, the tree's triumph over death is celebrated by adorning the cross with gold and jewels. Work of the period is notable for its synthetic employment of 'Pagan' and 'Christian' imagery as can be seen on the Franks Casket or the Kirkby Stephen cross shaft which appears to conflate the image of Christ crucified with that of Woden/Odin bound upon the Tree of Life.[28] Others have read the poem's blend of Christian themes with the heroic conventions as an Anglo-Saxon embrace and re-imagining, rather than conquest, of Christianity.[29]

The poem may be viewed as both Christian and pre-Christian. Bruce Mitchell notes that The Dream of the Rood is "the central literary document for understanding [the] resolution of competing cultures which was the presiding concern of the Christian Anglo-Saxons".[24] Within the single culture of the Anglo-Saxons is the conflicting Germanic heroic tradition and the Christian doctrine of forgiveness and self-sacrifice, the influences of which are readily seen in the poetry of the period. Thus, for instance, in The Dream of the Rood, Christ is presented as a "heroic warrior, eagerly leaping on the Cross to do battle with death; the Cross is a loyal retainer who is painfully and paradoxically forced to participate in his Lord's execution".[30] Christ can also be seen as "an Anglo-Saxon warrior lord, who is served by his thanes, especially on the cross and who rewards them at the feast of glory in Heaven".[31] Thus, the crucifixion of Christ is a victory, because Christ could have fought His enemies, but chose to die. John Canuteson believes that the poem "show[s] Christ's willingness, indeed His eagerness, to embrace His fate, [and] it also reveals the physical details of what happens to a man, rather than a god, on the Cross".[32] This image of Christ as a 'heroic lord' or a 'heroic warrior' is seen frequently in Anglo-Saxon (and Germanic) literature and follows in line with the theme of understanding Christianity through pre-Christian Germanic tradition. In this way, "the poem resolves not only the pagan-Christian tensions within Anglo-Saxon culture but also current doctrinal discussions concerning the nature of Christ, who was both God and man, both human and divine".[33]

J. A. Burrow notes an interesting paradox within the poem in how the Cross is set up to be the way to Salvation: the Cross states that it cannot fall and it must stay strong to fulfill the will of God. However, to fulfill this grace of God, the Cross has to be a critical component in Jesus' death.[34] This puts a whole new light on the actions of Jesus during the Crucifixion. Neither Jesus nor the Cross is given the role of the helpless victim in the poem, but instead both stand firm. The Cross says, Jesus is depicted as the strong conqueror and is made to appear a "heroic German lord, one who dies to save his troops".[35] Instead of accepting crucifixion, he 'embraces' the Cross and takes on all the sins of mankind.

Mary Dockray-Miller argues that the sexual imagery identified by Faith Patten, discussed below, functions to 'feminize' the Cross in order for it to mirror the heightened masculinity of the warrior Christ in the poem.[31]

Faith Patten identified 'sexual imagery' in the poem between the Cross and the Christ figure, noting in particular lines 39–42, when Christ embraces the Cross after having 'unclothed himself' and leapt onto it.[6] This interpretation was expanded upon by John Canuteson, who argued that this embrace is a 'logical extension of the implications of the marriage of Christ and the Church', and that it becomes 'a kind of marriage consummation' in the poem.[32]

Rebecca Hinton identifies the resemblance of the poem to early medieval Irish sacramental penance, with the parallels between the concept of sin, the object of confession, and the role of the confessor. She traces the establishment of the practice of penance in England from Theodore of Tarsus, archbishop of Canterbury from 668 to 690, deriving from the Irish confession philosophy. Within the poem, Hinton reads the dream as a confession of sorts, ending with the narrator invigorated, his "spirit longing to start."[36]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.