Loading AI tools

Croatian politician and sociologist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

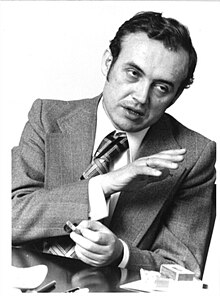

Stipe Šuvar (17 February 1936 – 29 June 2004) was a Croatian politician and sociologist who was regarded to have been one of the most influential communist politicians in the League of Communists of Croatia (SKH) in SR Croatia in the 1980s during Yugoslavia.

Stipe Šuvar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vice-President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia | |

| In office 15 May 1990 – 24 August 1990 | |

| President | Borisav Jović |

| Prime Minister | Ante Marković |

| Preceded by | Borisav Jović |

| Succeeded by | Stjepan Mesić |

| Member of the Presidency of Yugoslavia for the Socialist Republic of Croatia | |

| In office 15 May 1989 – 24 August 1990 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Josip Vrhovec |

| Succeeded by | Stjepan Mesić |

| President of the Presidency of the LCY Central Committee | |

| In office 30 June 1988 – 17 May 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Boško Krunić |

| Succeeded by | Milan Pančevski |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 February 1936 Zagvozd, Yugoslavia (now Croatia) |

| Died | 29 June 2004 (aged 68) Zagreb, Croatia |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Mira Šuvar |

He entered top politics in 1972 being co-opted to the Central Committee of SKH. Two years later he became SR Croatia's minister of education and performed a controversial educational reform in Croatia. In 1980s he was a member of the Presidency of SKH central committee, then a member and President of the Presidency of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ).

In 1989 Croatian Parliament appointed Šuvar to represent SR Croatia in the eight-member Presidency of Yugoslavia but dismissed him one year later when, after the first multi-party elections in Croatia, it was already dominated by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) of Franjo Tuđman.

After the collapse of communism and the breakup of Yugoslavia, Šuvar founded the now defunct magazine Hrvatska ljevica (1994–2005) and a minor leftist party, the Socialist Labour Party of Croatia (SRP). Šuvar was known as a lifelong Marxist ideologue and opponent of nationalism.

Šuvar was born in 1936 in the Dalmatian village of Zagvozd. At the age of 19, he joined the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ). He studied at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Law, where he received a sociology doctorate in 1965. From 1960 until the 1980s he taught sociology at the University of Zagreb and at other universities in Yugoslavia, and published a number of books on both sociological and political topics.[1]

From 1963 to 1972 he was editor-in-chief of the Zagreb monthly Naše teme. In 1969, Šuvar in a polemic with Matica hrvatska official Šime Đodan denied the claims by Maspok ideologists that Croatia was being exploited by other Yugoslav republics. During time Šuvar was also active in several other periodicals, lastly in SKJ-run "Socijalizam" (Socialism) in the 1980s.[2]

In 1972, after the Maspok had been defeated and the leadership led by Mika Tripalo purged from the top of SKH, Šuvar was co-opted to the SKH central committee. Two years later he became Croatian secretary (minister) for culture and education and remained in that office until 1982.[3][4]

From 1982 to 1986, Šuvar was a member of the Presidium of SKH. From 1983 onwards, he was responsible for the ideological section of the party and, holding this office, in 1984 he organized a discussion about the "ideological struggle on the cultural front." Participants of the meeting were handed materials containing quotations from texts of 186 (mostly Serbian and Slovenian) authors which had been published in the Yugoslav media between 1982 and 1984. These texts were labeled as unacceptable, anti-socialist and more or less "openly nationalist." The document, nicknamed the White Book (B(ij)ela knjiga) or "Flowers of Evil" (Cv(ij)eće zla), was condemned especially by the Serbian intelligentsia as a Stalinist attack on freedom of thought.[5]

In 1986, Šuvar was elected to the SKJ Presidium as a representative of the Croatian SKH along with Ivica Račan. In June 1988, when the Presidium was about to choose a new chairman between Šuvar and Račan, Šuvar prevailed. At the vote he was backed up, among others, by the Serbian members of the Presidium including Slobodan Milošević. However, only one month later controversies between Šuvar and Milošević emerged because of Šuvar's opposition to the anti-bureaucratic revolution organized by the Serbian leader.[6] In October 1988, when a dispute between Šuvar and Milošević at one Presidium session went public, a campaign for Šuvar's dismissal took place in Serbia.[7]

In early October 1988, rallies in Novi Sad supported by Milošević forced out the local Vojvodina party leadership, while Montenegrin establishment, with the support of the SKJ Presidium and of the federal Presidency, resisted rallies in Titograd. On 17 October, in the heated political atmosphere, the SKJ Central Committee met at its 17th plenary session in Belgrade to discuss "general political situation" in Yugoslavia.

Yugoslav media expected the session to be crucial for country’s future and also more than 200 foreign journalists were about to attend the plenum.[8] In his address, Šuvar called for economic and political reforms "within the frameworks of socialism" and for combating nationalism in the entire country. He expressed the conviction that nationalism wouldn’t succeed neither in destroying Yugoslavia nor in turning it into a centralized country.[9] Most of the Yugoslav communist officials’ speeches agreed about the need for reforms and unity, and the plenum was therefore seen as successful by most Yugoslav media. However, mutual attacks of the republics’ leaders started again after the session, and the political situation kept worsening.[10][11]

In January 1989, after the Montenegrin leadership was brought down during new rallies in Titograd, and a few days before the 20th session of the SKJ Central Committee was to take place, a conference of the Vojvodinian communists (SKV) attacked Šuvar and asked the SKJ Presidium to dismiss him, which was supported by the Serbian leadership, and was followed by a new mudslinging campaign in the Serbian media and Party organizations against Šuvar. The Yugoslav Federal Presidency, afraid of the overthrow of the SKJ leadership in the same way as it had happened with local party leaderships in Vojvodina and Montenegro, put the country's police forces in the state of alert and warned the Serbian leadership of a state of emergency being possibly declared if more demonstrations took place in Belgrade during the session.

The session itself was uneventful, but didn't bring any positive results.[12] Before the session Šuvar had promised that he would "call things their right names" meaning, supposedly, directly condemn Milošević's policy - but at the end he withdrew a harsh version of his report and instead presented a less explicit version.[13][14] The proposal to dismiss Šuvar from the position of SKJ leader was rejected by the party Presidium in March 1989. Out of the 20 Presidium members, in favour of the dismissal were only six, including Milošević and other Serbian representatives.[15]

At the same time, Šuvar was continuously opposing separatist tendencies in his own SR Croatia and in SR Slovenia. He frequently warned against the rise of Croat nationalism which, in his view, was at that time most visible in discussions about language policy.[16] Šuvar also opposed demands of Slovenians for a broader autonomy of their republic, and criticized public attacks on the Yugoslav People's Army in the Slovenian media. In June 1988 at the SKJ Presidium session discussing the case of Janez Janša, Šuvar said:

According to Šuvar himself, in June 1988 the three Slovenian members of the Presidium voted for Račan to become Presidium chairman.[14] In February 1989, Šuvar negotiated with the miners in the 1989 Kosovo miners' strike as a representative of SKJ.[18]

In the spring of 1989, the Croatian Parliament appointed Šuvar to represent SR Croatia in the Yugoslav Presidency, the collective body serving as head of state of Yugoslavia. In April 1990 multi-party parliamentary elections took place in Croatia, in which Franjo Tuđman's recently formed HDZ won on an independence platform. Tuđman asked Šuvar to resign, but he refused; on 24 August 1990 Croatian Parliament dismissed Šuvar from the Yugoslav Presidency, choosing Stipe Mesić of HDZ in his place.

On that occasion in the Parliament, Šuvar held his last speech while holding a political office. He warned against hostilities and possible ethnic conflicts in Yugoslavia and in Croatia, called for a new agreement on Yugoslavia or for its peaceful dissolution, and for respecting rights of ethnic Serbs living in Croatia. He expressed the hope for a new rise of the left in its struggle for socialism, and ironically congratulated HDZ for completing the Serbian-driven anti-bureaucratic revolution by eliminating him from politics. The speech was twice interrupted by an uproar of the HDZ deputies and followed by sharply critical replies of several of them, while nobody of Šuvar’s own SKH party spoke in his defence.[14][19][20]

On 1 November 1990, he left SKH just two days before the party convention in which they were reformed as a social democratic party. He stated his reasons in a letter saying that the new SDP-SKH was no longer "a left-wing or a revolutionary party" but an "ordinary civil party" just like the rest of the political spectrum.[21]

After he had left politics, Šuvar returned to Zagreb University as a professor of sociology. In 1994 he founded the magazine Hrvatska ljevica (The Croatian Left) and in 1997, he returned to politics by creating the Socialist Labour Party of Croatia (SRP). Šuvar succeeded in bringing some respectable personalities into the fold, but SRP never managed to win more than 1% of the votes in parliamentary elections. He was the chairman of SRP until 2004, when, shortly before his death, he resigned.

Šuvar was a vocal critic of nationalist policies of the regime of Franjo Tuđman in the 1990s which targeted Serbs of Croatia, especially after the 1995 Operation Storm.[22] After 1990, Šuvar also continued publishing books, and gave a number of interviews in which he reflected on both his role in politics of former Yugoslavia and events after the country's break-up. Šuvar, unlike many of his former communist colleagues, did not abandon socialist ideals even after the collapse of communism, and stayed staunchly critical towards all kinds of nationalism, including the one of his own nation.[23]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.