Loading AI tools

American comic artist (1926–2018) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

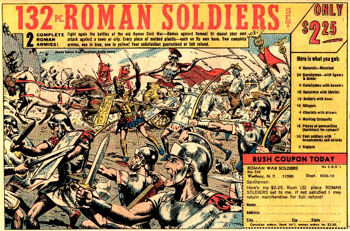

Russell Heath Jr.[1] (September 29, 1926 – August 23, 2018)[2] was an American artist best known for his comic book work, particularly his DC Comics war stories and his 1960s art for Playboy magazine's "Little Annie Fanny" feature. He also produced commercial art, two pieces of which, depicting Roman and Revolutionary War battle scenes for toy soldier sets, became familiar pieces of Americana after gracing the back covers of countless comic books from the early 1960s to early 1970s.

| Russ Heath | |

|---|---|

Heath at the November 2008 Big Apple Comic Con | |

| Born | Russell Heath Jr. September 29, 1926 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | August 23, 2018 (aged 91) Long Beach, California, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Penciller |

Notable works | "Little Annie Fanny", All-American Men of War |

| Awards | 1997 Inkpot Award 2009 Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame 2018 Inkwell Awards Stacy Aragon Special Recognition Award |

A number of Heath's drawings of fighter jets and pilots in DC Comics' All-American Men of War were the uncredited and uncompensated basis for pop artist Roy Lichtenstein's oil paintings Blam, Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!, and Brattata.[3][4][5]

Heath was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2009.

Raised in New Jersey as an only child, Russ Heath at an early age became interested in drawing. "My father used to be a cowboy, so as a little kid I was influenced by Western artists of the time. Will James was one, an artist-writer—I had most of his books. Charlie Russell was my favorite because his work was absolutely authentic, because he drew what he lived ..."[6] Largely self-taught, Heath began freelancing for comics during summers while he was in high school, and both penciled and inked at least two installments of the naval feature "Hammerhead Hawley" in Holyoke Publishing's Captain Aero Comics vol. 2, #2 (Sept. 1942) and vol. 3, #12 (April 1944).[7]

Heath was in Montclair, New Jersey's Montclair High School class of 1945.[8] It is unclear if Heath, anxious to fight in World War II, graduated; in a 2004 interview, he recalls going "into the Air Force in my senior year of high school, in 1945," after having been "put in an accelerated class so I could get through with high school. I almost made it, but then the Air Force called me and in I went."[9] He served stateside for nine months, drawing cartoons for his camp newspaper, but due to a clerical error, he said,[9] he was on neither the military payroll nor any official duty roster for a significant portion of his time. A 2011 article in his hometown newspaper said that, "After a short stint in the military, Heath came back to Montclair, graduated from high school, got married and started a family."[8]

While spending several weeks arranging appointments with artists for an assistant's job, Heath was hired as an office "gofer" for the large Manhattan advertising agency Benton & Bowles, earning $35 weekly. He continued looking for work as an artist on his lunch hour, and in 1947, landed a $75-a-week staff position at Timely Comics, the 1940s predecessor of Marvel Comics. Initially working in the Timely offices, Heath, like some of the other staffers, soon found it more efficient to work at home. He and his new wife had been living at his parents' home and continued to do so for two more years, while saving money for their own house. By the mid-1960s, however, they had children and were divorced.[10]

The artist said in 2004 he believed his first work for Timely was a Western story featuring the Two-Gun Kid.[10] Historians have tentatively identified his first work as either a Kid Colt story in the omnibus series Wild Western #4 (Nov. 1948); the second Two-Gun Kid story in Two-Gun Kid #5 (Dec. 1948), "Guns Blast in Thunder Pass;" and the Two-Gun Kid story in Wild Western #5 (Dec. 1948), while confirming Heath art on the Kid Colt story that same issue. Heath's first superhero story is tentatively identified as the seven-page Witness story, "Fate Fixed a Fight," in Captain America Comics #71 (March 1949).[7]

Heath drew several Western stories for such Timely comics as Wild Western, All Western Winners, Arizona Kid, Black Rider, Western Outlaws, and Reno Browne, Hollywood's Greatest Cowgirl. As Timely evolved into Marvel's 1950s iteration, known as Atlas Comics, Heath expanded into other genres. He drew the December 1950 premiere of the two-issue superhero series Marvel Boy, as well as scattered science fiction anthology stories (in Venus, Journey into Unknown Worlds, and Men's Adventures); crime drama (Justice); horror stories and covers (Adventures into Terror, Marvel Tales, Menace, Mystic, Spellbound, Strange Tales, Uncanny Tales, the cover of Journey into Mystery #1), satiric humor (Wild, Mad), and war stories.[7]

Heath produced combat stories both for the wide line of Timely war titles and the first issue (Aug. 1951) of EC Comics' celebrated Frontline Combat. He contributed to Mad #14, illustrating Harvey Kurtzman's parody of Plastic Man. Heath later did the first of many decades' worth of war work for DC Comics, with Our Army at War #23 and Star Spangled War Stories #22, both cover-dated June 1954.[7]

Other 1950s work includes an issue of 3-D Comics from St. John Publications and "The Return of the Human Torch" (minus the opening page, drawn by character-creator Carl Burgos) in Young Men #24 (Dec. 1953),[7][11] the flagship of Atlas' ill-fated effort to revive superheroes, which had fallen out of fashion in the post-war U.S.

Heath co-created with writer-editor Robert Kanigher the feature "The Haunted Tank" in G.I. Combat #87 (May 1961).[12] Heath stated in a 1999 interview that "I didn't like "The Haunted Tank" [in G.I. Combat] as much ... I liked less because there was always the same four characters – J.E.B. Stuart plus his three buddies – virtually the same story every issue: He'd be talking to this ghost, over and over again. I couldn't believe kids kept wanting to look at it."[13] Also with Kanigher, Heath co-created and drew the first issues of DC's Sea Devils, about a team of scuba-diving adventurers.[7][14] DC Comics writer and executive Paul Levitz described Heath in 2010 as "[A] master of texture and lighting and meticulous levels of detail. Given the chance he'd draw every barnacle on a sunken pirate ship."[15] Several of Kanigher's characters were combined into a single feature titled "The Losers". Their first appearance as a group was with the Haunted Tank crew in G.I. Combat #138 (Oct.–Nov. 1969) drawn by Heath.[16]

Various Heath drawings of fighter jets in DC Comics' All-American Men of War were the uncredited and uncompensated basis for pop artist Roy Lichtenstein's oil paintings Whaam!, Blam, Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!, and Brattata.[3][4][5][17][18][19][20][21]

Heath became known for the authenticity of his military comics. The artist would buy uniforms, helmets and radios at Army surplus stores to use as reference, which peer Joe Kubert said

... set him apart. He could illustrate mechanical things like rifles and tanks in a realistic way that few other artists could. He would build models of the things he would draw prior to drawing them and his stuff would come out right on the button. Other artists used to keep what they called a swipe file – pictures of things they may have to draw someday that they could use for reference. Russ' work was so good, other artists used it as reference.[8]

Sometime in the 1960s, Heath drew two pieces of commercial art that became familiar bits of Americana after gracing the back covers of countless comic books through the early 1970s: advertisements for toy soldier sets, depicting Roman and Revolutionary War battle scenes.[1] As Heath described in a 2000s interview,

I got fifty bucks for those two separate pages. ... A lot of people didn't know I did them because [the client] didn't want them signed. I did have a small "RH" on the lower left-hand corner of the Revolutionary soldiers and I don't remember about the Roman soldiers. Then [customers] would blame me [when the actual toys were not as depicted]; I'd never seen the damned things, because they're like a bas relief or whatever they call it. They're not fully formed, not three dimensional. It would be flat things that were shaped a little and the kids felt gypped and they figured that it was my fault.[22]

Heath was one of the artists who sometimes assisted Kurtzman and Will Elder on their regular Playboy strip "Little Annie Fanny".[23] Writer Mark Evanier described Heath making the most of one such assignment:

One time when deadlines were nearing meltdown, Harvey Kurtzman called Heath in to assist in a marathon work session at the Playboy Mansion in Chicago. Russ flew in and was given a room there, and spent many days aiding Kurtzman and artist Will Elder in getting one installment done of the strip. When it was completed, Kurtzman and Elder left ... but Heath just stayed. And stayed. And stayed some more. He had a free room as well as free meals whenever he wanted them from Hef's 24-hour kitchen. He also had access to whatever young ladies were lounging about ... so he thought, 'Why leave?' He decided to live there until someone told him to get out ... and for months, no one did. Everyone just kind of assumed he belonged there. It took quite a while before someone realized he didn't and threw him and his drawing table out.[23]

Heath recalled in 2001 that as an adult he lived "seven years in Manhattan, seven years in Chicago and seven years in Connecticut", in the town of Westport, before moving to California in 1978.[24] There he worked as an animator for Saturday-morning TV cartoons and later did commissioned art for comics fans. A rare example of Heath working on super-hero material was his inking Michael Golden's penciled artwork on Mister Miracle #24 and 25.[25] Heath and writer Cary Bates launched The Lone Ranger comic strip on September 13, 1981.[26] His last comic-book story was penciling and inking the four-page flashback sequence of the 22-page story "The Mortal Iron Fist, Conclusion", in Marvel Comics' The Immortal Iron Fist #20 (Jan. 2009)[7][27] He went on to provide cover art for publisher Aardvark-Vanaheim's satiric comic book glamourpuss #11–13 (Jan.–May 2010), with his last known published comics work the one-page illustration "That Russ Heath Girl #4", appearing in issue #19 (May 2011).[28] He lived in Van Nuys, California, where in his 80s he had knee surgery after The Hero Initiative and the Comic Art Professional Society of Los Angeles raised money to help pay for an operation.[8][27]

Heath received an Inkpot Award in 1997[29] and was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2009.[30] Heath received the Sergio Award from the Comic Art Professional Society in 2010[23] and the National Cartoonists Society's Milton Caniff Award in 2014.[31] In 2018, Heath was awarded the Inkwell Awards Stacy Aragon Special Recognition Award for his lifetime achievement as comic book inker.[32]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.