Loading AI tools

American painter From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rolf Armstrong (April 21, 1889 – February 22, 1960) was an American commercial artist specializing in glamorous depictions of female subjects. He is best known for his magazine covers and calendar art. In 1960 the New York Times dubbed him the “creator of the calendar girl.”[5] His commercial career extended from 1912 to 1960, the great majority of his original work being done in pastel.

Rolf Armstrong | |

|---|---|

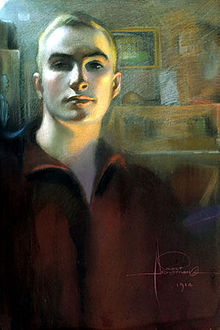

Self portrait, 1914, pastel on board | |

| Born | John Scott Armstrong[1] April 21, 1889[2] Bay City, Michigan,[2] United States |

| Died | February 22, 1960 (aged 70)[3] |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Institute of Chicago[4] |

| Known for | Pin-up art, Illustrator, Glamour Art |

Rolf Armstrong was born John Scott Armstrong in Bay City, Michigan.[6] His parents were Richard and Harriet (Scott) Armstrong. His father owned the Boy-Line and Fire Boat Company, comprising fire boats and passenger ships on the Great Lakes, including one that served the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. Due to increasingly financial difficulties, the family left Bay City in 1899 and moved to Detroit, Michigan.

Rolf had two brothers and a sister, all at least twenty years older than himself. After his father's death in 1903, Rolf lived for about three years with his eldest brother, William, in Seattle, Washington. There he became close to William's son, Robert Armstrong, who later achieved fame as a film and television actor best known for his role in King Kong (1933). Rolf's brother, Paul, also had a brief but successful career as a New York playwright (1907-1915).[6]

After studying in Chicago and living and working in New York for several years, Rolf married Claire Louise Frisbie, a free-lance writer, in 1919.[6] They had no children. Around 1930 they moved to Bayside, Queens, where Rolf had recently designed and built a house on an inlet of Little Neck Bay. Rolf had learned to sail as a child and kept as many as eight sailboats at this property. Among these was Mannequin, a decked sailing canoe he designed and raced, twice winning the American Canoe Association Elliott Trophy (1932, 1934). About 1935 Rolf and Louise left Bayside for Southern California in an apparent attempt to benefit from the movie industry. In 1939 they obtained a divorce, after which Louise immediately married Robert Armstrong.

In 1939 Armstrong moved back to Manhattan, taking up residence for the next twenty years in the Hotel des Artistes. In the 1950s he traveled extensively, visiting Europe, Tahiti, and Hawaii. After several trips to the latter, he retired there permanently in late 1959. Shortly after this move, he suffered a mild heart attack, followed by a fatal attack on February 22, 1960.[6] In accordance with his wishes, his ashes were scattered from an overlook on Nuʻuanu Pali. In 1997, surviving friends and admirers arranged for placement of a grave marker at the Armstrong family plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Detroit, Michigan.

Rolf enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1907 under the name Jack Armstrong.[6] One of his four original roommates was Thomas Hart Benton, the noted painter and muralist. Armstrong moved to New York City immediately upon graduation in 1911 and lived for a time in the Lincoln Arcade where he attended classes held by Robert Henri at the Henri School of Art. It was around this time that he changed his name to Rolf.

Armstrong traveled to Paris in 1919 to study at the Académie Julian, and in 1921 he went to Minneapolis to study calendar production at Brown & Bigelow.[citation needed]

Armstrong's first known published work is the cover of Judge magazine from January 27, 1912, also known as “A Live Wire.”[6] Throughout this decade he built a reputation as a cover artist, producing over sixty covers for a variety of magazines including Metropolitan, Puck, Every Week, American Magazine, and The Stewart Lever.

During the 1920s Armstrong achieved considerable commercial success creating a total of 65 portraits of silent screen actors (all but one female) for the covers of Photoplay, Screenland and other movie fan magazines. Among his better known subjects were Mary Pickford, Bebe Daniels, and Greta Garbo. As his popularity grew, he was the subject of featurettes in Photoplay and Screenland. Armstrong's work for the Pictorial Review was largely responsible for that magazine achieving a circulation of more than two million by 1926.[citation needed] Other published works in the twenties include a cover for Collier's (1926) and two covers for the Saturday Evening Post (1923). In 1925 Armstrong contracted with the newly launched College Humor, a monthly magazine aimed at male college students, producing 68 covers over the following decade.

As color photography came into its own, demand for original cover art waned in the 1930s. Armstrong's last known cover image is College Humor, March 1936. The great majority of Armstrong's magazine covers show the head only, and the originals that are known are relatively small works (less than 24” in greatest dimension). Approximately 200 total magazine images are known.

The earliest known calendar featuring an Armstrong image is from 1915. During the twenties and early thirties Armstrong's work appeared with increasing frequency as calendar art. These were often reused or reworked magazine cover images. One of the most popular of such images was Hello Everybody, originally the March 1929 cover of College Humor. This was the first College Humor cover showing the entire figure, as opposed to the head only.

During this period Armstrong also produced works specifically for the calendar industry. Notable exceptions to the small pastels typically done by Armstrong in this period were five life-size oil paintings of the female figure entitled Cleopatra, The Enchantress, Arabian Nights, Carmen, and Song of India. All were published as calendar art, and having never appeared as magazine covers, were almost certainly created for this purpose.

Calendar images became a larger part of Armstrong's work in the early thirties and his chief source of income within a few years. In 1927 Armstrong was the best-selling calendar artist at Brown & Bigelow[citation needed] and in 1933 the Thomas D. Murphy Calendar Company signed him to produce a series of paintings for their line.[citation needed] Around 1939 he landed a lucrative contract to produce exclusively for Brown & Bigelow, the largest calendar publisher at that time. Under this contract, which was renewed throughout the forties and fifties, he produced approximately six original pieces per year (fewer in later years).

Most of Armstrong's later works produced for the calendar industry depict the entire figure, were done in pastel, and were of intermediate size (about 36” in greatest dimension). Approximately 180 calendar images are known, not including reworked cover images.

Many if not most of Armstrong's covers and early calendar images were reused for sheet music, postcards, and all manner of advertising items. In addition, Armstrong produced at least another 60 original images for magazine or other ads, including a series for RCA around 1930. About the same number of unpublished sketches, student works, and portraits are known.

Along with Howard Chandler Christy, Norman Rockwell, and numerous other artists, Armstrong lived and worked during what is called the “Golden Age of American Illustration.”[7] This age began with the development of four-color printing in the late 19th century, was fueled by the advent of magazines supported by advertising, and declined after the introduction of color photography in the 1930s.

In a career of almost 50 years, Rolf Armstrong produced over 500 works. He prided himself on the fact that he worked almost exclusively from live models, as opposed to photographic references.[6] Armstrong eschewed the term “illustrator,” referring to himself as a “portrayer of feminine beauty.” The term “glamour” has been applied to his work retrospectively in an effort to distinguish his style from that of artists who may depict female subjects, but not in a glamorizing way. For the same reason, while the term “pin-up” is often applied to his work, its use is controversial among Armstrong enthusiasts.[6]

In Pin Up Dreams: The Glamour Art of Rolf Armstrong, the authors present glamour art generally, and the work of Rolf Armstrong specifically, as characteristic of the early 20th century, especially the years 1920-1950 “after World War I had freed women of their excessive modesty, but before World War II had made certain subtleties seem outdated.” The glamour girl as depicted by Armstrong is described as “beautiful of face and form...always vivacious and often mysterious, exuding romance and subtle sexuality.”[6]

In addition to societal attitudes toward women, Armstrong's work illustrates other many other aspects of American life in the early 20th century. These include trends in hairstyles and fashion, popular color schemes, changing concepts of ideal beauty, and cultural trends such as Egyptology (1920s), female participation in sports (1930s), patriotism (1940s), and Hawaiian and western themes (1950s).

Armstrong's better-known images include Naomi aka Portrait of Martha Mansfield (1920), The Dream Girl (1924), The Bride Pompeiian Beauty Panel (1927), It (1927), Dreamy Eyes (1927), The Enchantress (1927), Queen of the Ball (1928), Hello Everybody (1929), Thinking of You (1930), Golden Girl (1933), How Am I Doing? (1940), On the Beam (1943), and Toast of the Town (1945).

In March 1940, Jewel Flowers, a girl from Lumberton, North Carolina, sent a picture of herself to Armstrong in response to an advert he had placed in the New York Times. Armstrong, 50 at the time, had been based at the Hotel des Artistes on West 67th Street in Manhattan since 1939, and was seeking new models. He invited Flowers for an interview. On March 25, 1940, Flowers began modeling for Armstrong. Their professional collaboration and friendship lasted two decades. The first painting, titled "How am I doing?", reportedly because Flowers, new to modeling, repeatedly asked Armstrong "How am I doing?" during the session, was first published after World War II began. It was Brown & Bigelow's best selling calendar for 1942 at a time when the company sold millions of calendars in America. It became one of Armstrong's most reproduced pictures. Flowers was popular with American servicemen during World War II, some of whom sent her letters proposing marriage. Armstrong's calendars and silhouettes of Flowers were copied onto bombers and other planes as nose art and painted on tank turrets. She became so well known during the war, although more as a famous face than by name, that a serviceman's letter addressed simply as "Jewel Flowers, New York City" was delivered correctly. For many American servicemen abroad, she represented the "Why We Fight" spirit. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's government enlisted her to help promote war bonds. The January 1, 1945 edition of TIME magazine included Armstrong's "Toast of the Town" painting of Flowers in an article about Calendar Art. The article noted that calendars with "girl paintings" were "bought heavily by foundries, machine shops, auto-supply dealers."

Flowers married in 1946. She and her husband resided in several locations while he attempted several business ventures, including Laguna Beach, California, Greenville, South Carolina and Reno, Nevada, where she reportedly worked as a card dealer, and New York City. According to Michael Wooldridge, coauthor of Pin up Dreams: The Glamour Art of Rolf Armstrong, Armstrong called her several times while she was following her husband's quest, attempting to persuade her to return to New York and model for him.

Her modeling career ended with Armstrong's death in 1960. He left a large proportion of his personal wealth to Flowers. Armstrong created approximately 50 to 60 works using Flowers as the model.

In the January 1930 issue of Screenland, Rolf Armstrong chose sixteen actresses to symbolize different colors. Here are the original captions and portraits in the order which they appeared in the magazine.[8]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.