Rod Serling

American screenwriter (1924–1975) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rodman Edward Serling (December 25, 1924 – June 28, 1975) was an American screenwriter and television producer best known for his live television dramas of the 1950s and his anthology television series The Twilight Zone. Serling was active in politics, both on and off the screen, and helped form television industry standards. He was known as the "angry young man" of Hollywood, clashing with television executives and sponsors over a wide range of issues, including censorship, racism, and war.

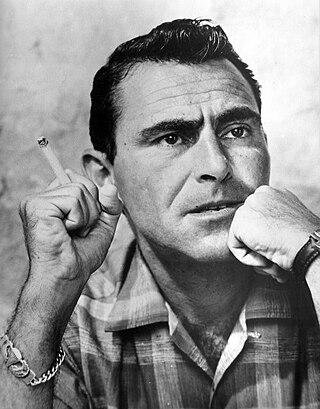

Rod Serling | |

|---|---|

Serling in 1959 | |

| Born | Rodman Edward Serling December 25, 1924 Syracuse, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 1975 (aged 50) Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Antioch College (B.A.) |

| Genre | |

| Years active | 1946–1975 |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse |

Carolyn Louise Kramer

(m. 1948) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Robert J. Serling (brother) |

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Serling was born on December 25, 1924, in Syracuse, New York, to a Jewish family.[2] He was the second of two sons born to Esther (née Cooper, 1893–1958), a homemaker, and Samuel Lawrence Serling (1892–1945).[3] Serling's father had worked as a secretary and amateur inventor before his children were born but took on his father-in-law's profession as a grocer to earn a steady income.[2]: 15 Sam Serling later became a butcher after the Great Depression forced the store to close. Rod had an older brother, novelist and aviation writer Robert J. Serling.[2]: 23 [4]

Serling spent most of his youth 70 mi (110 km) south of Syracuse in Binghamton, New York, after his family moved there in 1926.[3] His parents encouraged his talents as a performer. Sam Serling built a small stage in the basement, where Rod often put on plays (with or without neighborhood children).[2]: 17–18 His older brother, writer Robert, recalled that, at the age of six or seven, Rod entertained himself for hours by acting out dialogue from pulp magazines or movies he had seen. Rod would often ask questions without waiting for their answers. On an hour trip from Binghamton to Syracuse, the rest of the family remained silent to see if Rod would notice their lack of participation. He did not, and he talked nonstop through the entire car ride.[3]

In elementary school, Serling was seen as the class clown and dismissed by many of his teachers as a lost cause.[2]: 19–20 His seventh-grade English teacher, Helen Foley, encouraged him to enter the school's public speaking extracurriculars.[2]: 19 He joined the debate team and was a speaker at his high school graduation. He began writing for the school newspaper, in which, according to the journalist Gordon Sander, he "established a reputation as a social activist".[2]: 19

Serling was interested in sports, and excelled at tennis and table tennis. When he attempted to join the varsity football team, he was told he was too small at 5 ft 4 in (163 cm) tall.[2]: 18–22

Serling was interested in radio and writing at an early age. He was an avid radio listener, especially interested in thrillers, fantasy, and horror shows. Arch Oboler and Norman Corwin were two of his favorite writers.[5] He also "did some staff work at a Binghamton radio station ... tried to write ... but never had anything published."[5] He was accepted into college during his senior year of high school. However, the United States was involved in World War II at the time, and Serling decided to enlist rather than start college immediately after he graduated from Binghamton Central High School in 1943.[4][6]

As editor of his high school newspaper, Serling encouraged his fellow students to support the war effort. He wanted to leave school before graduation to join the fight, but his civics teacher talked him into waiting for graduation. "War is a temporary thing," Gus Youngstrom told him. "It ends. Education doesn't. Without your degree, where will you be after the war?"[2]: 36

American military service

Summarize

Perspective

Serling enlisted in the U.S. Army the morning after high school graduation, following his brother Robert.[2]: 34, 37

Serling began his military career in 1943 at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, under General Joseph May Swing and Colonel Orin D. Haugen[2]: 36–37 and served in the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 11th Airborne Division.[4] He eventually reached the rank of Technician Fourth Grade (T/4).[7]

Over the next year of paratrooper training, Serling and others began boxing to vent aggression. He competed as a flyweight and had 17 bouts, rising to the second round of the division finals before being knocked out.[2]: 40 He was remembered for his Berserker style, and for "getting his nose broken in his first bout and again in the last bout".[8] He tried his hand at the Golden Gloves, with little success.[5]

On April 25, 1944, Serling received his orders and saw that he was being sent west to California. He knew that he would be fighting against the Empire of Japan rather than Nazi Germany. This disappointed him because he had hoped to help fight against Adolf Hitler.[2]: 40–41 In May, he was assigned to the Pacific Theater in New Guinea and the Philippine islands.[9]

In November 1944, his division first saw combat, landing in the Philippines. The 11th Airborne Division was not used as paratroopers, however, but as light infantry during the Battle of Leyte. The division helped secure the area after the five divisions that had gone ashore earlier.[2]: 43

For a variety of reasons, Serling was transferred to the 511th's demolition platoon, nicknamed "The Death Squad" for its high casualty rate. According to Sergeant Frank Lewis, leader of the demolitions squad, "He screwed up somewhere along the line. Apparently he got on someone's nerves."[2]: 45 Lewis also judged that Serling was not suited to be a field soldier: "he didn't have the wits or aggressiveness required for combat."[2]: 45 At one point, Lewis, Serling, and others were in a firefight, trapped in a foxhole. As they waited for darkness, Lewis noticed that Serling had not reloaded any of his extra magazines. Serling sometimes went exploring on his own, against orders, and got lost.[2]: 45

Serling's time in Leyte shaped his writing and political views for the rest of his life. He saw death every day while in the Philippines, at the hands of his enemies and his allies, and through freak accidents such as that which killed another Jewish private, Melvin Levy. Levy was delivering a comic monologue for the platoon as they rested under a palm tree when a food crate was dropped from a plane above, decapitating him. Serling led the funeral services for Levy and placed a Star of David over his grave.[2]: 45 Serling later set several of his scripts in the Philippines and used the unpredictability of death as a theme in much of his writing.[2]: 46 In the 1960 Twilight Zone episode "The Purple Testament", a prologue written by Serling stated, "Infantry platoon, U.S. Army, Philippine Islands, 1945. These are the faces of the young men who fight, as if some omniscient painter had mixed a tube of oils that were at one time earth brown, dust gray, blood red, beard black, and fear—yellow white, and these men were the models. For this is the province of combat, and these are the faces of war."

Serling returned from the successful mission in Leyte with two wounds, including one to his kneecap,[2]: 47 but neither kept him from combat when General Douglas MacArthur deployed the paratroopers for their usual purpose on February 3, 1945. Colonel Haugen led the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment as it landed on Tagaytay Ridge, met the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment and marched into Manila. It met minimal resistance until it reached the city, where Vice Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi had arranged his 17,000 troops behind a maze of traps and guns and ordered them to fight to the death.[2]: 47–49 During the next month, Serling's unit battled block by block for control of Manila.

When portions of the city were taken from Japanese control, local civilians sometimes showed their gratitude by throwing parties and hosting banquets. During one of these parties, Serling and his comrades were fired upon, resulting in many soldier and civilian deaths. Serling, still a private after three years, caught the attention of Sergeant Lewis when he ran into the line of fire to rescue a performer who had been on stage when the artillery started firing.[2]: 49

As it moved in on Iwabuchi's stronghold, Serling's regiment had a 50% casualty rate, with over 400 men killed or wounded. Serling was wounded and three comrades were killed by shrapnel from rounds fired at his roving demolition team by an antiaircraft gun.[2]: 50 He was sent to New Guinea to recover but soon returned to Manila to finish "cleaning up".

Serling's final assignment was as part of the occupation force in Japan.[2]: 51 During his military service, Private Serling was awarded the Purple Heart, the Bronze Star,[10] and the Philippine Liberation Medal.[4][11]

Serling's combat experience affected him deeply and influenced much of his writing. It left him with nightmares and flashbacks for the rest of his life.[4] He said, "I was bitter about everything and at loose ends when I got out of the service. I think I turned to writing to get it off my chest."[3]

Awards

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Postwar life, education, and family

Summarize

Perspective

After being discharged from the Army in 1946, Serling worked at a rehabilitation hospital while recovering from his wounds. His knee troubled him for years. Later, his wife, Carol, became accustomed to the sound of him falling on the stairs when his knee would buckle.[6]

When he was fit enough, he used the federal G.I. bill's educational benefits[8] and disability payments[6] to enroll in the physical education program at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. He had been accepted to Antioch (his brother's alma mater) while in high school.[2]: 53 His interests led him to the theater department and then to broadcasting.[6] He changed his major to Literature and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1950.[3] "I was kind of mixed up and restless, and I kind of liked their work-for-a-term, go-to-school-for-a-term set-up," he recounted.[2]: 53

As part of his studies, Serling became active in the campus radio station, an experience that proved useful in his future career. He wrote, directed, and acted in many radio programs on campus, then around the state, as part of his work study.[12] Here he met Carolyn Louise "Carol" Kramer,[13] a fellow student, who later became his wife. At first, she refused to date him because of his promiscuous campus reputation, but she eventually changed her mind.[3] He joined the Unitarian church in college,[4] which allowed him to marry Kramer on July 31, 1948.[3] They had two daughters, Jodi (born 1952) and Anne (born 1955).[3][14][15]

Carol Serling's maternal grandmother, Louise Taft Orton Caldwell,[2]: 60 had a summer home on Cayuga Lake in Interlaken, New York, which was the honeymoon destination for the newlyweds. The Serling family continued to use this house annually throughout Rod's life, missing only two summers in the years when his daughters were born.[6]

For extra money in his college years, Serling worked part-time testing parachutes for the United States Army Air Forces. According to his radio station coworkers, he received $50 for each successful jump and had once been paid $500 (half before and half if he survived) for a hazardous test.[2]: 58 His last test jump was a few weeks before his wedding. In one instance, he earned $1,000 for testing a jet ejection seat that had killed the previous three testers.[16][2]: 61

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Radio

Serling volunteered at WNYC in New York as an actor and writer in the summer of 1946.[5] The next year, he worked at that station as a paid intern in his Antioch work-study program.[2]: 57 He then took odd jobs in other radio stations in New York and Ohio.[17] "I learned 'time', writing for a medium that is measured in seconds," Serling later said of his early experiences.[5]

While attending college, Serling worked at the Antioch Broadcasting System's radio workshop and was managing the station within a couple of years. He then took charge of full-scale radio productions at Antioch which were broadcast on WJEM, in Springfield. He wrote and directed the programs and acted in them when needed. He created the entire output for the 1948–1949 school year. With one exception (an adaptation), all the writing that year was his original work.[5]

While in college, Serling won his first accolade as a writer. The radio program, Dr. Christian, had started an annual scriptwriting contest eight years earlier. Thousands of scripts were sent in annually, but very few could be produced.[5] Serling won a trip to New York City and $500 for his radio script "To Live a Dream".[18] He and his new wife, Carol, attended the awards broadcast on May 18, 1949, where he and the other winners were interviewed by the star of Dr. Christian, Jean Hersholt. One of the other winners that day was Earl Hamner, Jr., who had also earned prizes in previous years. Serling's first job out of college was with WLW radio as copy writer. The position had just been vacated by Hamner who left to concentrate on his writing. Hamner later wrote scripts for Serling's The Twilight Zone.[5]

In addition to earning $45 to $50 a week at the college radio station, Serling attempted to make a living selling freelance scripts of radio programs, but the industry at that time was involved in many lawsuits, which affected willingness to take on new writers (some whose scripts were rejected would often hear a similar plot produced, claim their work had been stolen, and sue for recompense).[5] Serling was rejected for reasons such as "heavy competition", "this script lacks professional quality", and "not what our audience prefers to listen to".[5]

In the autumn of 1949, Martin Horrell of Grand Central Station (a radio program known for romances and light dramas) rejected one of Serling's scripts about boxing, because his mostly female listeners "have told us in no uncertain terms that prize fight stories aren't what they like most". Horrell advised that "the script would be far better for sight than for sound only, because in any radio presentation, the fights are not seen. Perhaps this is a baby you should try on some of the producers of television shows."[5]

Realizing the boxing story was not right for Grand Central Station, Serling submitted a lighter piece called Hop Off the Express and Grab a Local, which became his first nationally broadcast piece on September 10, 1949.[5] His Dr. Christian script aired on November 30 of that year.

Serling began his professional writing career in 1950, when he earned $75 a week as a network continuity writer for WLW radio in Cincinnati, Ohio.[5][6] While at WLW, he continued to freelance. He sold several radio and television scripts to WLW's parent company, Crosley Broadcasting Corporation. After selling the scripts, Serling had no further involvement with them. They were sold by Crosley to local stations across the United States.[5]

Serling submitted an idea for a weekly radio show in which the ghosts of a young boy and girl killed in World War II would look through train windows and comment on day-to-day human life as it moved around the country. This idea was changed significantly but was produced from October 1950 to February 1951 as Adventure Express, a drama about a girl and boy who travel by train with their uncle. Each week they found adventure in a new town and got involved with the local residents.[5]

Other radio programs for which Serling wrote scripts include Leave It to Kathy, Our America, and Builders of Destiny. During the production of these, he became acquainted with a voice actor, Jay Overholts, who later became a regular on The Twilight Zone.[5]

Serling said of his time as a staff writer for radio:

From a writing point of view, radio ate up ideas that might have put food on the table for weeks at a future freelancing date. The minute you tie yourself down to a radio or TV station, you write around the clock. You rip out ideas, many of them irreplaceable. They go on and consequently can never go on again. And you've sold them for $50 a week. You can't afford to give away ideas—they're too damn hard to come by. If I had it to do over, I wouldn't staff-write at all. I'd find some other way to support myself while getting a start as a writer.[5]

Serling believed radio was not living up to its potential, later saying, "Radio, in terms of ... drama, dug its own grave. It had aimed downward, had become cheap and unbelievable, and had willingly settled for second best."[2]: 69 He opined that there were very few radio writers who would be remembered for their literary contributions.[2]: 69

Television

I think Rod would have been one of the first to say he hit the new industry, television, at exactly the right time. The first job he got out of school was as a continuity writer at (radio station) WLW in Cincinnati. He worked there for over a year before he could free-lance. At that point, he was really working on television scripts. [I]n 1951 and 1952, the new industry was grabbing up a lot of material and needed it. It was a very propitious time to be graduating from school and getting ready to find a profession.

—Carol Serling, Los Angeles Times, 1990 interview[12]

Serling moved from radio to television, as a writer for WKRC-TV in Cincinnati. His duties included writing testimonial advertisements for dubious medical remedies and scripts for a comedy duo.[3] He continued at WKRC after graduation and, amidst the mostly dreary day-to-day work, also created a series of scripts for a live television program, The Storm, as well as for other anthology dramas (a format which was in demand by networks based in New York).[4] Following a full day of classes (or, in later years, work), he spent evenings on his own, writing. He sent manuscripts to publishers and received forty rejection slips during these early years.[3]

In 1950, Serling hired Blanche Gaines as an agent. His radio scripts received more rejections, so he began rewriting them for television. Whenever a script was rejected by one program, he would resubmit it to another, eventually finding a home for many in either radio or television.[5]

As Serling's college years ended, his scripts began to sell. He continued to write for television[8] and eventually left WKRC to become a full-time freelance writer. He recalled, "Writing is a demanding profession and a selfish one. And because it is selfish and demanding, because it is compulsive and exacting, I didn't embrace it. I succumbed to it."[3]

According to his wife, Serling "just up and quit one day, during the winter of 1952, about six months before our first daughter Jody was born—though he was also doing some freelancing and working on a weekly dramatic show for another Cincinnati station."[6] He and his family moved to Connecticut in early 1953. Here he made a living by writing for the live dramatic anthology shows that were prevalent at the time, including Kraft Television Theatre, Appointment with Adventure and Hallmark Hall of Fame.[3] By the end of 1954, his agent convinced him he needed to move to New York, "where the action is."[6]

The writer Marc Scott Zicree, who spent years researching his book The Twilight Zone Companion, noted, "Sometimes the situations were clichéd, the characters two-dimensional, but always there was at least some search for an emotional truth, some attempt to make a statement on the human condition."[3]

Gaining fame

In 1955, the nationwide Kraft Television Theatre televised a program based on Serling's 72nd script. To Serling, it was just another script, and he missed the first live broadcast. He and his wife hired a babysitter for the night and told her, "no one would call because we had just moved to town. And the phone just started ringing and didn't stop for years!"[6] The title of this episode was "Patterns", and it soon changed his life.

"Patterns" dramatized the power struggle between a veteran corporate boss running out of ideas and energy and the bright, young executive being groomed to take his place. Instead of firing the loyal employee and risk tarnishing his own reputation, the boss enlists him into a campaign to push aside his competition.[19] Serling modeled the character of the boss on his former commander, Colonel Orin Haugen.[2]: 37

The New York Times critic Jack Gould called the show "one of the high points in the TV medium's evolution" and said, "[f]or sheer power of narrative, forcefulness of characterization and brilliant climax, Mr. Serling's work is a creative triumph."[19] Robert Lewis Shayon stated in Saturday Review, "in the years I have been watching television I do not recall being so engaged by a drama, nor so stimulated to challenge the haunting conclusions of an hour's entertainment."[3] The episode was a hit with the audience as well, and a second live show was staged by popular demand one month later.[20] During the time between the two shows, Kraft executives negotiated with people from Hollywood over the rights to "Patterns". Kraft said they were considering rebroadcasting "Patterns", unless the play or motion picture rights were sold first.[21]

Immediately following the original broadcast of "Patterns", Serling was inundated with offers of permanent jobs, congratulations, and requests for novels, plays, and television or radio scripts.[20] He quickly sold many of his earlier, lower-quality works and watched in dismay as they were published. Critics expressed concern that he was not living up to his promise and began to doubt he was able to recreate the quality of writing that "Patterns" had shown.[3]

Serling then wrote "Requiem for a Heavyweight" for the television series Playhouse 90 in 1956, again gaining praise from critics.[22]

In the autumn of 1957, the Serling family moved to California. When television was new, shows aired live from New York, but as studios began to tape their shows, the business moved from the East Coast to the West Coast.[6] The Serlings would live in California for much of his life, but they kept property in Binghamton and Cayuga Lake as retreats for when he needed time alone.[6]

Corporate censorship

The early years of television often saw sponsors working as editors and censors. Serling was often forced to change his scripts after corporate sponsors read them and found something they felt was too controversial. They were wary of anything they thought might make them look bad to consumers, so references to many contemporary social issues were omitted, as were references to anything that might compete commercially with a sponsor. For instance, the line "Got a match?" was deleted because one of the sponsors of "Requiem for a Heavyweight" was Ronson lighters.[3]

The initial story-line of his teleplay Noon on Doomsday (aired April 25, 1956) was set in the Southern United States about the lynching of a Jewish pawnbroker. However, when Serling mentioned in a radio interview that it was inspired by the events and racism that led to the murder of Emmett Till, censorship by advertisers and the TV network resulted in significant changes. The program as shown was set in New England and concerned the killing of an unknown foreigner.[23] He subsequently returned to the Till events when writing A Town Has Turned to Dust for 'Playhouse 90' but had to set it a century in the past and remove any inter-racial dynamics before it would be produced by CBS TV.[23]

Gould, The New York Times reviewer, added this editorial note at the end of a glowing review for A Town Has Turned to Dust, a show about racism and bigotry in a small Southwestern town: "'Playhouse 90' and Mr. Serling had to fight executive interference ... before getting their play on the air last night. The theater people of Hollywood have reason to be proud of their stand in the viewers' behalf."[24]

Frustrated by seeing his scripts divested of political statements and ethnic identities (and having a reference to the Chrysler Building removed from a script sponsored by Ford), Serling decided the only way to avoid such artistic interference was to create his own show. In an interview with Mike Wallace, he said, "I don't want to fight anymore. I don't want to have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don't want to have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best. I don't want to have to compromise all the time, which in essence is what a television writer does if he wants to put on controversial themes."[3]

Serling submitted "The Time Element" to CBS, intending it to be a pilot for his new weekly show, The Twilight Zone. Instead, CBS used the science fiction script for a new show produced by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, in 1958. The story concerns a man who has vivid nightmares of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The man goes to a psychiatrist and, after the session, the twist ending (a device which Serling became known for) reveals the "patient" had died at Pearl Harbor, and the psychiatrist was the one actually having the vivid dreams.[3] The episode received so much positive fan response that CBS agreed to let Serling go ahead with his pilot for The Twilight Zone.[3]

The Storm

Before The Twilight Zone, Serling created a local television show in Cincinnati on WKRC-TV, The Storm, in the early 1950s. Several of these scripts were rewritten for later use on national network TV.[25] A copy of an episode is located in the Cincinnati Museum Center Historical Cincinnati Library on videotape.[26]

The Twilight Zone

In early 1959,[27] Serling formed his own film production company, Cayuga Productions, and in July 1959 signed an exclusive three-year contract with CBS, stipulating that he would continue delivering telescripts for Playhouse 90, as well as create, write, and produce new properties for the network (one of which became the new series, The Twilight Zone).[28][29][30][31] On October 2, 1959, the Twilight Zone series, premiered on CBS.[4]

For this series, Serling fought hard to get and maintain creative control. He hired scriptwriters he respected, such as Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont. In an interview, Serling said the show's science fiction format would not be controversial[32] with sponsors, network executives, or the general public and would escape censorship, unlike the earlier script for Playhouse 90.

Serling drew on his own experience for many episodes, frequently about boxing, military life, and airplane pilots. The Twilight Zone incorporated his social views on racial relations, somewhat veiled in the science fiction and fantasy elements of the shows. Occasionally, the point was quite blunt, such as in the episode "I Am the Night—Color Me Black", in which hatred caused a dark cloud to form in a small town in the American Midwest and spread across the world. Many Twilight Zone stories reflected his views on gender roles, featuring quick-thinking, resilient women as well as shrewish, nagging wives.

The Twilight Zone aired for five seasons (the first three presented half-hour episodes, the fourth had hour-long episodes, and the fifth returned to the half-hour format). It won many television and drama awards and drew critical acclaim for Serling and his co-workers. Although it had loyal fans, The Twilight Zone had only moderate ratings and was twice canceled and revived. After five years and 156 episodes (92 written by Serling), he grew weary of the series. In 1964, he decided not to oppose its third and final cancellation.

Serling sold the rights to The Twilight Zone to CBS. His wife later claimed he did this partly because he believed that his own production company, Cayuga Productions, would never recoup the production costs of the programs, which frequently went over budget.

The Twilight Zone eventually resurfaced in the form of a 1983 film by Warner Bros. Former Twilight Zone actor Burgess Meredith was cast as the film's narrator, but does not appear on screen. There have been three attempts to revive the television series with mostly new scripts. In 1985, CBS used Charles Aidman (and later Robin Ward) as the narrator. In 2002, UPN featured Forest Whitaker in the role of narrator.[33] In 2019, CBS made a third attempt at a successful revival, with Jordan Peele taking on producing duties as well as being host and narrator.[34]

A Carol for Another Christmas

A Carol for Another Christmas was a 1964 American television movie, scripted by Rod Serling as a modernization of Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol and a plea for global cooperation between nations. It was telecast only once, on December 28, 1964.[35] The only television movie directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, this was the film in which Peter Sellers gave his first performance after a series of near-fatal heart attacks in the wake of his marriage to Britt Ekland. Sellers portrayed a demagogue in an apocalyptic Christmas.

Other television

Many of The Twilight Zone episodes were made as planned pilots for their own television series. One such was "Mr. Bevis," planned as a fantasy-comedy series in late 1959 though Cayuga Productions, but the pilot was later aired as an episode of Twilight Zone.[36][37][38] In November 1963, Serling made frequent Twilight Zone writer and co-producer William Froug a partner in Cayuga Productions.[39] The pair developed a new hour-long series titled Jeopardy Run (of no relation to Jeopardy!), about the "hazardous adventures of an undercover man who, provocatively, takes on dangerous tasks for various government agencies to continually prove his patriotism in the face of disloyalty accusations."[40] The pilot was filmed Hong Kong in December 1963, starring Steve Forrest.[40] Another thriller one-hour program was to be titled The Chase for CBS.[41] Another property the pair developed was titled Agnes, set to star Wally Cox, who gets heckled by a talking computer, for which "From Agnes—With Love" was filmed as a pilot but later aired as a Twilight Zone episode).[39][40]

In March 1964, it was reported that ABC had optioned a television series based on Serling's book Witches, Warlocks and Werewolves, to be written and produced through Cayuga Productions.[42] Serling originally planed for a 60-minute western television series called The Loner to start airing in the 1960 season, as a Cayuga Productions for CBS.[38] However, he told reporters that CBS had shelved the series because he was not able to dedicate enough time to writing original scripts for that series with his commitment to Twilight Zone.[38] Years later, the series was finally picked up and ran from the fall of 1965 to April 1966. CBS asked Serling to have more action and less character interaction. He refused to comply, even though the show had received poor reviews and low ratings.[4] In 1966, Serling formed a new film production company, Finger Lakes Productions.[43][44]

Night Gallery

In 1969, NBC aired a television film pilot for a new series, Night Gallery, written by Serling. Set in a dimly lit museum after hours, the pilot film featured Serling (as on-camera host) playing the curator, who introduced three tales of the macabre, unveiling canvases that would appear in the subsequent story segments. Its brief first season (consisting of only six episodes) was rotated with three other shows airing in the same time slot; this wheel show was entitled Four in One. The series generally focused more on horror and suspense than The Twilight Zone did. On the insistence of the producer Jack Laird, Night Gallery also began including brief comedic "blackout" sketches during its second season, which Serling greatly disdained.[45] He stated "I thought they [the blackout sketches] distorted the thread of what we were trying to do on Night Gallery. I don't think one can show Edgar Allan Poe and then come back with Flip Wilson for 34 seconds. I just don't think they fit."[46]

No longer wanting the burden of an executive position, Serling sidestepped an offer to retain creative control of content, a decision he would come to regret.[45] Although discontented with some of the scripts and creative choices of Jack Laird, Serling continued to submit his work and ultimately wrote over a third of the series' scripts. By season three, however, many of his contributions were being rejected or heavily altered.[citation needed] Night Gallery was cancelled in 1973. NBC later combined episodes of the short-lived paranormal series The Sixth Sense with Night Gallery, in order to increase the number of episodes available in syndication. Serling was reportedly paid $100,000 to film introductions for these repackaged episodes.[47][48]

Other television

In a stylistic departure from his earlier work, Serling briefly hosted the first version of the game show Liar's Club in 1969.[49]

In the 1970s, Serling appeared in television commercials for Ford, Radio Shack, Ziebart[50] and the Japanese automaker Mazda. He also made occasional acting appearances, all in material he didn't write. Serling appears as a version of himself (but named "Mr. Zone") in a comedic bit on The Jack Benny Program; he appears in a 1962 episode of the short-lived sitcom Ichabod and Me in the role of reclusive counterculture novelist Eugene Hollinfield; and in a 1972 episode of the crime drama Ironside entitled "Bubble, Bubble, Toil, and Murder" (which also featured a young Jodie Foster), in which he plays a small role as the proprietor of an occult magic shop.

Other radio

The Zero Hour

Serling returned to radio late in his career with The Zero Hour (also known as Hollywood Radio Theater) in 1973. The drama anthology series featured tales of mystery, adventure, and suspense, airing in stereo for two seasons. Serling hosted the program but did not write any of the scripts. The series ended on July 26, 1974.

Fantasy Park

Serling's final radio performance was even more unusual: Fantasy Park was a 48-hour-long rock concert aired by nearly 200 stations in 1974 and 1975. The program, written and produced by McLendon National Productions Director Steve Blackson, featured performances by dozens of rock stars of the day, and even reunited the Beatles. It was also completely imaginary—as KNUS Program Director Beau Weaver put it, a "theatre-of-the-mind for the '70s". The concert used record albums, many recorded live in concert, plus crowd noise, interviews, schedule updates by host Fred Kennedy, and other sound effects. (Stations that aired the special were reportedly inundated by callers demanding to know how to get to the nonexistent concert.) KNUS general manager Bart McLendon recruited Serling to record the host segments, bumpers, custom promos, and television spots.

Serling wrote the disclaimers, which aired each hour: "Hello, this is Rod Serling and welcome back to Fantasy Park—the crowds here today are unreal." "This is Fantasy Park—the greatest live concert—never held."

Teaching

Serling kept his schedule full. When he was not writing, promoting, or producing his work, he often spoke on college campuses around the country.[6] He taught week-long seminars in which students would watch and critique films. In the political climate of the 1960s, he often felt a stronger connection to the older students in his evening classes.[6] Serling's critique of high school student writing was a pivotal experience for writer J. Michael Straczynski.[51]

By the fourth season of Twilight Zone, Serling was exhausted and turned much of the writing over to a trusted stable of screenwriters, authoring only seven episodes. Desiring to take a break and clear his mind, he took a one-year teaching job as writer in residence at Antioch College, Ohio. He taught classes in the 1962–63 school year on writing and drama and a survey course covering the "social and historical implications of the media."[3][4] He used this time to teach as well as work on a new screenplay, Seven Days in May, which he also co-produced through Cayuga Productions.[4][52]

Later he taught at Ithaca College, from the late 1960s until his death in 1975.[3][53] He was one of the first guest teachers at the Sherwood Oaks Experimental College in Hollywood, California. Audio recordings of his lectures there are included as bonus features on some Twilight Zone home video editions.

Themes

Summarize

Perspective

No one could know Serling, or view or read his work, without recognizing his deep affection for humanity ... and his determination to enlarge our horizons by giving us a better understanding of ourselves.

According to his wife, Carol, Serling often said that "the ultimate obscenity is not caring, not doing something about what you feel, not feeling! Just drawing back and drawing in, becoming narcissistic."[6] This philosophy can be seen in his writing. Some themes appear again and again in his writing, many of which are concerned with war and politics. Another common theme is equality among all people.

Antiwar activism

Serling's experiences as a soldier left him with strong opinions about the use of military force. He was an outspoken antiwar activist, especially during the Vietnam War.[4] He supported antiwar politicians, notably U.S. senator Eugene McCarthy in his presidential campaign in 1968.[4]

"The Rack" is an example of Serling's use of television to speak his mind on political issues. This script for The United States Steel Hour tells the story of an army captain charged with collaborating with the North Koreans. The New York Times reviewer J. P. Shanley called it "controversial and compelling".[54] Serling tackled a question that was much in the media at the time: should veterans be charged with a crime if they cooperated with the enemy while under duress? In this courtroom drama, the accused is put on trial for helping the enemy by urging fellow prisoners of war to cooperate with their captors. Serling offers many valid arguments on behalf of both the defense and the prosecution. Each has a strong case, but in the end, the captain is found guilty. There is no Serling narration to conclude the drama, as he had become famous for in The Twilight Zone—instead, the audience is left to make their own conclusions after the verdict has been rendered.[54]

"No Christmas This Year" was a script written early in Serling's career, around 1950, but was never produced. It told of a place that no longer celebrated Christmas, although none of the residents know why it has been canceled. Meanwhile, at the North Pole, the audience sees Santa Claus dealing with striking elves. Rather than creating toys and candy, the North Pole manufactures a diversity of bombs and offensive gases. Santa has been shot at on his route, and an elf was hit by shrapnel.[5]

"24 Men to a Plane" recounts Serling's first combat jump into the area around Manila in 1945. The combat jump became a fiasco after the jumpmaster in the first plane dropped his men too early, causing every subsequent plane to drop in synchronization with the mistake.[2]: 48

Racial equality

A Town Has Turned to Dust received a positive review from the critic Jack Gould, who was known for being straightforward to the point of being harsh in his reviews. He called A Town Has Turned to Dust "a raw, tough and at the same time deeply moving outcry against prejudice."[24] Set in a Southwestern town in a deep drought, it sees poverty and despair turn racial tensions deadly when the ineffectual sheriff is unable to stand against the town. A young Mexican boy is lynched, and the town as a whole is to blame. A second lynching is in the works after a series of events leads again to the town turning against the Mexicans. This time, the sheriff stands strong, and the first boy's brother is saved, even as the town is not. "Mr. Serling incorporated his protest against prejudice in vivid dialogue and sound situations. He made his point that hate for a fellow being leads only to the ultimate destruction of the bigoted."[24]

Serling took his 1972 screenplay for the film The Man from the Irving Wallace novel of the same title. The black senator from New Hampshire and president pro tempore of the Senate, played by James Earl Jones, assumes the U.S. presidency by succession.

Death

Serling was said to smoke three to four packs of cigarettes a day.[55] On May 3, 1975, he had a heart attack and was hospitalized. He spent two weeks at Tompkins County Community Hospital before being released.[2]: 217 A second heart attack two weeks later forced doctors to agree that open-heart surgery, although considered risky at the time, was required.[2]: 218 [56] The ten-hour-long procedure was performed on June 26, but Serling had a third heart attack on the operating table and died two days later at Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester, New York.[57] He was 50 years old.[53]

His funeral and burial took place on July 2 at Lake View Cemetery, Interlaken, (Seneca County), New York. A memorial was held at Cornell University's Sage Chapel on July 7, 1975.[53] Speakers at the memorial included his daughter Anne and the Reverend John F. Hayward.[2]: 218

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Television

Serling began his career when television was a new medium. The first public viewing of an all-electronic television was presented by inventor Philo Farnsworth at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia on August 25, 1934, when Serling was nine years old. Commercial television officially started on July 1, 1941. At the time, there were fewer than seven thousand television sets in the United States, and very few of those were in private homes.[58]: 21 Only five months later, the U.S. entered World War II, and the television business was put on hold until the war's end,[58]: 22 as many of the unsold sets were obtained by the government and repurposed to train air-raid wardens.[2]: 57 After World War II ended, money began flowing toward the new medium of television, coinciding with the beginning of Serling's writing career. Early programming consisted of newsreels, sporting events and what would be called public-access television today. It was not until 1948 that filmed dramas were first shown, beginning with a show called Public Prosecutor.[58]: 25 Serling began having serious dramas produced in 1950 and is given credit as one of the first to write scripts specifically for television. As such, he is said to have helped legitimize television drama.[2]: 28

Serling worried that television was on the verge of suffering the same decline as radio. He encouraged sponsors to see television as a platform for the kind of dramatic entertainment that could address important social matters through subtle meanings, instead of being "an animated billboard".[59]

The format of writing for television was changing rapidly in the early years, but eventually, it settled into a pattern of commercial breaks on each quarter-hour. Writers were forced to work these breaks into their scripts. Serling's response to this convention was, "How can you put out a meaningful drama when every fifteen minutes proceedings are interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits with toilet paper? No dramatic art form should be dictated and controlled by men whose training and instincts are cut of an entirely different cloth. The fact remains that these gentlemen sell consumer goods, not an art form."[32] Throughout his career, Serling helped to mold the future of television.

Writing for multiple media

As early as 1955, Jack Gould, of the New York Times, commented on the close ties that were then being created between television and movies. Serling was among the first to use both forms, turning his early television successes, "Patterns" and "The Rack", into full-length movies.[60] Up to that time, many established writers were unwilling to write for television because the programs were viewed only once and then stored in a vault, never to be seen again.[61]

Beginning of the rerun

After the first showing of "Patterns", the studio received such positive feedback that it produced a repeat performance, the first time a television program had been replayed at the request of the audience. Although successful shows had sometimes been recreated after two years or more, this was the first time a show was recreated exactly—with the same cast and crew—as it had been originally broadcast.[62] The second live performance, only a month later, was equally successful and inspired New York Times critic Jack Gould to write an essay on the use of replays on television. He stated that "Patterns" was a prime example of a drama that should be seen more than once, whereas a single broadcast was the norm for television shows of the day. Sponsors believed that creating new shows every week would assure them the largest possible audience, so they purchased a new script for each night. Gould suggested that as new networks were opened and the viewers were given more choices, the percentage of viewers would spread among the offerings. "Patterns" was proof that a second showing could gain more viewers because those who missed the first showing could see the second, thus increasing the audience for sponsors.[61]

After the first showing of "Patterns", the studio received such positive feedback that it produced a repeat performance, the first time a television program had been replayed at the request of the audience. Although successful shows had sometimes been recreated after two years or more, this was the first time a show was recreated exactly—with the same cast and crew—as it had been originally broadcast.[62] The second live performance, only a month later, was equally successful and inspired New York Times critic Jack Gould to write an essay on the use of replays on television. He stated that "Patterns" was a prime example of a drama that should be seen more than once, whereas a single broadcast was the norm for television shows of the day. Sponsors believed that creating new shows every week would assure them the largest possible audience, so they purchased a new script for each night. Gould suggested that as new networks were opened and the viewers were given more choices, the percentage of viewers would spread among the offerings. "Patterns" was proof that a second showing could gain more viewers because those who missed the first showing could see the second, thus increasing the audience for sponsors.[61]

Effects on popular culture

Summarize

Perspective

During his lifetime

In December 1966, the made-for-television movie The Doomsday Flight aired. The fictional plot concerned an airplane with a bomb aboard. If the plane landed without the ransom money being paid, the aircraft would explode. The bomb was set with an altitude trigger that would detonate it if the plane dropped below four thousand feet. The show was one of the highest-rated of the television season, but both Serling and his brother Robert, a technical advisor on the project (a specialist in aviation), regretted making the film. After the film was aired, a rash of copycats telephoned in ransom demands to most of the largest airlines. Serling was truly devastated by what his script had encouraged. He told reporters who flocked to interview him, "I wish to Christ that I had written a stagecoach drama starring John Wayne instead."[63]

In the 1962 Perry Mason episode "The Case of the Promoter's Pillbox", the titular promoter falsely claims that a teleplay for a TV pilot, "Mr. Nobody", is being rewritten by Serling as a personal favor to him. Later, Mason, who does know Serling, shows the original teleplay to him, saying that Serling wants to help the young man who wrote the teleplay to get a start in his writing career. The man's mother then expresses to Serling her desire to tell her stories from years of running a drug store.[64][better source needed]

Legacy

You're traveling through another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind ... a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination—your next stop, the Twilight Zone.

—Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone, introduction

Serling is indelibly woven into modern popular culture because of the enduring popularity of The Twilight Zone.[65] Serling's widow, Carol, maintained that the cult status that surrounded both her husband and his shows continues to be a surprise, "as I'm sure it would have been to him."[12] "It won't go away. It keeps bobbing up. ... Each year, I think, well, that's it—and then something else turns up."[12] She survived him to the age of 90, dying on January 9, 2020,[66] and participated in the continuing interest in Rod's work, sometimes preparing them for a new format and editing a publication about Rod that she founded, The Twilight Zone Magazine, as well as many activities to promote his legacy.

The Twilight Zone has been rerun, re-created and re-imagined since going off the air in 1964. It has been released in comic book form,[67] as a magazine, a film, and three additional television series from 1985 to 1989, from 2002 to 2003, and from 2019 to 2020. In 1988, J. Michael Straczynski scripted Serling's outline "Our Selena Is Dying" for the 1980s Twilight Zone series.

Some of Serling's works are now available in graphic novels. Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone is a series of adaptations by Mark Kneece and Rich Ellis based on original scripts written by Serling.[68] Several episodes were adapted into novel form for pulp fiction books by Serling himself.

The Twilight Zone is not the only Serling work to reappear. In 1994, Rod Serling's Lost Classics released two never-before-seen works that Carol Serling found in her garage. The first was an outline called, "The Theatre", which Richard Matheson expanded. The second was a complete script written by Serling, "Where the Dead Are".

Serling and his work on The Twilight Zone inspired the Disney theme park attraction The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, which debuted at Disney's Hollywood Studios at the Walt Disney World Resort in Florida in 1994. Serling appears in the attraction through the use of repurposed archival footage, and voice actor Mark Silverman provides the dubbing of Serling's dialogue for the attraction at both Hollywood Studios and the defunct version at Disney California Adventure in Anaheim.[69] The ride takes place in the once-elegant Hollywood Tower Hotel that was struck by lightning, which caused the mysterious disappearance of five guests. Riders enter an abandoned elevator shaft as they become part of a "lost episode" of The Twilight Zone, with the attraction taking guests up 13 stories and dropping them multiple times.

More than 30 years after his death, Serling was digitally resurrected for an episode of the television series Medium that aired on November 21, 2005. Filmed partially in 3-D, it opened with Serling's introducing the episode and instructing viewers when to put on their 3-D glasses. This was accomplished using footage from The Twilight Zone episode "The Midnight Sun" and digitally manipulating Serling's mouth to match new dialogue spoken by voice actor Mark Silverman. The plot involved paintings coming to life, a nod to both The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery.

On August 11, 2009, the United States Postal Service released its Early TV Memories commemorative stamp collection honoring notable television programs. One of the 20 stamps honored The Twilight Zone and featured a portrait of Serling.[70]

Through a mix of computer animation, a simulated version of Serling appeared at the end of the "Blurryman" episode of the 2019 revival of The Twilight Zone. This was done with a facial performance by Ryan Hesp, motion-capture by Jefferson Black, and a voice reprisal by Mark Silverman.

There are several memorials to Serling in his hometown of Binghamton, New York. Annually since 1995, Binghamton High School, Serling's alma mater, primarily in partnership with WSKG-TV,[71] hosts the Rod Serling Video Festival for students in kindergarten through grade 12. The festival encourages young people to engage in filmmaking.[72][73] Likewise, the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation hosts Serlingfest - a celebration of The Twilight Zone and Serling’s work - in Binghamton annually. A New York State Historic Marker for Serling stands outside Binghamton High School.[74] On September 15, 2024, a statue of Serling was unveiled in Recreation Park following state grants[75] and online crowdfunding for the memorial,[76] the base of which contains a quote from Serling: “Everybody has a hometown/Binghamton’s mine.”

Filmography

As creator

- 1959–64: The Twilight Zone

- 1965–66: The Loner

- 1970–73: Night Gallery

As narrator

- 1968–75: The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

- 1969–70: Liar's Club (host)

- 1973–75: In Search of...

- 1973: Encounter with the Unknown

- 1974: Monsters! Mysteries or Myths?

- 1974: UFOs: Past, Present, and Future

- 1974: Phantom of the Paradise

As writer (film)

- 1956: Patterns

- 1956: The Rack

- 1958: Saddle the Wind

- 1962: Incident in an Alley

- 1962: Requiem for a Heavyweight

- 1963: The Yellow Canary

- 1964: Seven Days in May

- 1964: A Carol for Another Christmas (TV film)

- 1966: Assault on a Queen

- 1966: The Doomsday Flight (TV film)

- 1968: Planet of the Apes (co-written with Michael Wilson)

- 1969: Night Gallery

- 1972: The Man

- 1976: Time Travelers (TV film)

- 1981: The Salamander (1976 screenplay)

- 1994: Rod Serling's Lost Classics (TV film, 1968 screenplay)

- 1997: In the Presence of Mine Enemies (TV film, 1960 screenplay)

- 2000: A Storm in Summer (TV film, 1970 screenplay)

As writer (television)

- 1953: A Long Time Till Dawn (Kraft Television Theatre)

- 1953: Old MacDonald Had a Curve (Kraft Television Theatre)

- 1955: Patterns (Kraft Television Theatre)

- 1955: The Director (The Jane Wyman Show)

- 1955: The Rack (The U.S. Steel Hour)

- 1956: The Arena (Studio One)

- 1956: The Champion (Climax!)

- 1956: Forbidden Area (Playhouse 90)

- 1956: Requiem for a Heavyweight (Playhouse 90)

- 1957: The Comedian (Playhouse 90)

- 1957: The Dark Side of the Earth (Playhouse 90)

- 1957: Panic Button (Playhouse 90)

- 1958: Nightmare at Ground Zero (Playhouse 90)

- 1958: Bomber's Moon (Playhouse 90)

- 1958: A Town Has Turned to Dust (Playhouse 90)

- 1958: The Velvet Alley (Playhouse 90)

- 1958: The Time Element (Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse)

- 1959: The Rank and File (Playhouse 90)

- 1960: In the Presence of Mine Enemies (Playhouse 90)

- 1963: It's Mental Work (Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre)

- 1969: Pilot (The New People)

- 1976: The Sad and Lonely Sundays (posthumously released)

Books

- Patterns: Four Television Plays, Bantam, 1957 (also includes scripts for The Rack, Old MacDonald Had a Curve, and Requiem for a Heavyweight)

- Stories from the Twilight Zone, Bantam (New York City), 1960

- More Stories from the Twilight Zone, Bantam, 1961

- New Stories from the Twilight Zone, Bantam, 1962

- From the Twilight Zone, Doubleday (Garden City, NJ), 1962

- Requiem for a Heavyweight: A Reading Version of the Dramatic Script, Bantam, 1962

- Rod Serling's Triple W: Witches, Warlocks and Werewolves; A Collection,(Editor) Bantam, 1963

- The Season to Be Wary (3 novellas, "Escape Route", "Color Scheme", and "Eyes"), Little, Brown (Boston, MA), 1967

- Devils and Demons: A Collection, Bantam, 1967 (Editor and author of introduction)

- Night Gallery, Bantam, 1971

- Night Gallery 2, Bantam, 1972

- Rod Serling's Other Worlds,(Editor) Bantam, 1978

Accolades

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

| Year | Association | Category | Work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Best Original Teleplay Writing | "Patterns" (Kraft Television Theatre) | Won |

| Best Television Adaptation | "The Champion" (Climax!) | Nominated | ||

| 1956 | Best Teleplay Writing | "Requiem for a Heavyweight" (Playhouse 90) | Won | |

| Peabody Awards | Personal Recognition for Writing | Won | ||

| 1958 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Best Teleplay Writing | "The Comedian" (Playhouse 90) | Won |

| 1959 | Best Writing of a Single Dramatic Program One Hour or Longer | "A Town Has Turned to Dust" (Playhouse 90) | Nominated | |

| 1960 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Writing Achievement in Drama | The Twilight Zone | Won |

| 1961 | Outstanding Writing Achievement in Drama | Won | ||

| 1962 | Outstanding Writing Achievement in Drama | Nominated | ||

| 1962 | Golden Globe Awards | Best TV Producer/Director | Won | |

| 1963 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Writing Achievement in Drama – Adaptation | "It's Mental Work" (Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre) | Won |

Posthumous honors

- 1985: Inducted into the Television Hall of Fame[77]

- 1985: A star honoring Serling can be found at 6840 Hollywood Blvd. on the Hollywood Walk of Fame[78]

- 2001: Nominated for a Daytime Emmy Award and Winner of a Writer Guild Award for the reusing of his script for the re-make of "A Storm in Century".

- 2007: Ranked No. 1 on TV Guide's "25 Greatest Sci-Fi Legends" list (the only non-fictitious person on the list)[79]

- 2008: Inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame[80]

Notes

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.