Loading AI tools

Ojibwe writer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Richard Wagamese (October 14, 1955 – March 10, 2017) was an Ojibwe Canadian author and journalist from the Wabaseemoong Independent Nations in Northwestern Ontario.[3] He was best known for his novel Indian Horse (2012), which won the Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature in 2013, and was a competing title in the 2013 edition of Canada Reads.[4]

Richard Wagamese | |

|---|---|

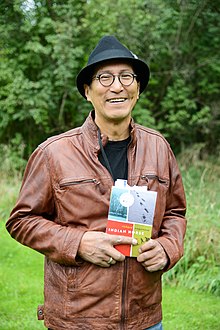

Wagamese at the Eden Mills Writers' Festival in 2013 | |

| Native name | Mushkotay Beezheekee Anakwat (Buffalo Cloud) |

| Born | October 14, 1955 Minaki, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | March 10, 2017 (aged 61)[1] Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada |

| Occupation | novelist, poet, television writer |

| Language | Ojibway; English |

| Genre | First Nations literature[2] |

| Notable works | Indian Horse |

| Notable awards | Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature (2013) |

It was adapted into a feature-length film, Indian Horse (2017), directed by Stephen Campanelli and released after Wagamese's death.[5]

In the essay "The Path to Healing", Wagamese described his first home as a tent hung from a spruce bough.[2] His family fished, hunted, and trapped. At the age of two, he and his three siblings were abandoned by adults on a binge drinking trip in Kenora. The children left their bush camp when they ran out of food and firewood, and sheltered at a railway depot, where they were found by a policeman.[6]

Wagamese later described his family by saying "each of the adults had suffered in an institution that tried to scrape the Indian out of their insides, and they came back to the bush raw, sore and aching."[2] His parents, Marjorie Wagamese and Stanley Raven, had been among the many native children who, under Canadian law, were removed from their families and forced to attend government-run residential schools, the primary purpose of which was to assimilate them to European-Canadian culture.[7]

After being taken from his family by the Children's Aid Society, Wagamese was raised in foster homes in northwestern Ontario before being adopted, at age nine, by a Presbyterian family in St. Catharines. They refused to allow him to maintain contact with his First Nations heritage and identity.[8][2] The beatings and abuse he endured in foster care and his adoptive home led him to leave at 16,[6] seeking to reconnect with Indigenous culture.[9] For a time he lived on the street, abusing drugs and alcohol, and was imprisoned several times.[10][11] During this time he also began frequenting public libraries, at first for shelter and later to read.[11]

Wagamese did not reunite with his family until age 23. After he recounted his experiences to them, an elder gave him the name Mushkotay Beezheekee Anakwat – Buffalo Cloud – and told him that his role was to tell stories.[2]

In his later life, Wagamese lived near Kamloops, British Columbia.[1] In 2010 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the city's Thompson Rivers University.[12]

He was married and divorced three times, and had two sons named Jason and Joshua, one of whom was estranged.[2] On March 10, 2017, two days after Embers: One Ojibway's Meditations was nominated for a BC Book Award, Wagamese died at his home of natural causes. He was engaged at the time of his death.[11] The film adaptation of his best-known novel, Indian Horse, was released later that year.

I did not speak my first Ojibwa word or set foot on my traditional territory until I was twenty-six. I did not know that I had a family, a history, a culture, a source for spirituality, a cosmology, or a traditional way of living. I had no awareness that I belonged somewhere.

Richard Wagamese, [6]

In 1979 Wagamese began his first job as a writer, working at New Breed, a First Nations publication.[11] With the encouragement of Lorna Crozier among others, he later worked as a journalist for the Calgary Herald.[12] Wagamese spent much of his time as a journalist interviewing residential school survivors.[13] He won a National Newspaper Award for writing in 1991.[14] His journalism also won the Native American Press Association Award twice and the National Aboriginal Communications Society award. His newspaper columns can be found in his anthology The Terrible Summer.[10] Wagamese stopped working full-time in journalism in 1993 but continued to write as a freelance journalist for publications such as The Globe and Mail.[11]

His debut novel Keeper 'n Me was published in 1994.[15] The book was co-winner with Roberta Rees's Beneath the Faceless Mountain of the Georges Bugnet Award for Novel at the 1995 Writers' Guild of Alberta's Alberta Literary Awards gala.[16]

He published five other novels, a book of poetry, two children's books, and five non-fiction books, including two memoirs.[1] He also wrote for the television series North of 60.[6] Throughout his writing life, Wagamese was renowned for his riveting live readings, consisting of passages from his works, traditional stories, anecdotes, and even stand-up comedy.[11] Wagamese is known as one of Canada's most prolific Indigenous authors.[17]

In 2012 he was given an Indspire Award as a representative of media and communications.[18] In 2012 he served as the Harvey Stevenson Southam Guest Lecturer in journalism at the University of Victoria. In 2013, he won the Canada Council for the Arts Molson Prize and the inaugural Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature for his novel Indian Horse.[10] Other awards included the Kouhi Award for outstanding contributions to the literature of Northwestern Ontario and the 2015 Writers' Trust of Canada's Matt Cohen Award for his body of work.[19]

In the same year, Canada's Super Channel announced that it was funding a film adaptation of Indian Horse, to be directed by Stephen Campanelli and written by Dennis Foon.[20] Clint Eastwood is one of the executive producers who contributed to the making of the film. Following Super Channel's filing for creditor protection, the film Indian Horse premiered theatrically at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival.[5]

His final novel, Starlight, was published posthumously in 2018.[21] A collection of stories and non-fiction writings, One Drum, was published posthumously in 2019.[22]

In 2022, Sea to Sky Entertainment and Grinding Halt Films announced that Foon, Campanelli and Jules Arita Koostachin were working on a film adaptation of Wagamese's 2009 novel Ragged Company.[23]

| Book | Awards & Honours |

|---|---|

| Keeper'n Me. Anchor Canada. 1994. ISBN 978-0-385-66283-3. | |

| The Terrible Summer. Warwick Publishing. 1996 ISBN 978-1895629637 | |

| A Quality of Light. Doubleday Canada. 1997. ISBN 978-0-385-25606-3. | |

| For Joshua: An Ojibway Father Teaches His Son. Anchor Canada. 2003. ISBN 978-0-385-65953-6. | |

| Dream Wheels. Anchor Canada. 2007. ISBN 978-0-385-66200-0. | 2007 Canadian Authors Association MOSAID Technologies Inc. Award for Fiction[24] |

| One Native Life. Douglas & McIntyre. 2008. ISBN 978-1-55365-364-6. | Included in The Globe and Mail's 2008 Top 100 Books of the Year |

| Ragged Company. Anchor Canada. 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-37263-5. | |

| One Story, One Song. Douglas & McIntyre. 2011. ISBN 978-1-55365-506-0. | 2011 George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature[3] |

| The Next Sure Thing. Raven Books. 2011. ISBN 9781554699001. | |

| Runaway Dreams. Ronsdale Press. 2011. ISBN 9781553801290. | |

| Indian Horse. Douglas & McIntyre. 2012. ISBN 978-1-55365-402-5. | 2013 Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature;[25] Shortlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award[10] |

| Him Standing. Orca Book Publishers LTD. 2013. ISBN 9781459801769. | |

| Medicine Walk. McClelland & Stewart. 2014. ISBN 978-0-7710-8918-3. | 2015 Banff Mountain Book Festival Grand Award[26] |

| Embers: One Ojibway's Meditations. Douglas & McIntyre. 2016. ISBN 978-1-77162-133-5. | 2017 Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award;[27] finalist for the BC Book Award[28] |

| Starlight. McClelland & Stewart. 2018. ISBN 978-0771070846. | |

| One Drum. Douglas & McIntyre. 2019. ISBN 978-1771622295. |

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.