Planning fallacy

Cognitive bias of underestimating time needed From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The planning fallacy is a phenomenon in which predictions about how much time will be needed to complete a future task display an optimism bias and underestimate the time needed. This phenomenon sometimes occurs regardless of the individual's knowledge that past tasks of a similar nature have taken longer to complete than generally planned.[1][2][3] The bias affects predictions only about one's own tasks. On the other hand, when outside observers predict task completion times, they tend to exhibit a pessimistic bias, overestimating the time needed.[4][5] The planning fallacy involves estimates of task completion times more optimistic than those encountered in similar projects in the past.

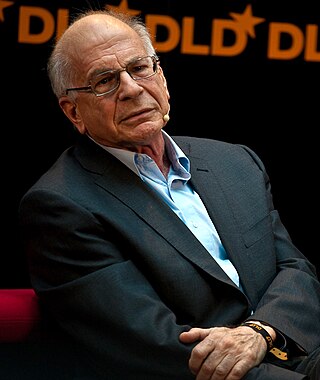

The planning fallacy was first proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979.[6][7] In 2003, Lovallo and Kahneman proposed an expanded definition as the tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions and at the same time overestimate the benefits of the same actions. According to this definition, the planning fallacy results in not only time overruns, but also cost overruns and benefit shortfalls.[8]

Empirical evidence

Summarize

Perspective

For individual tasks

In a 1994 study, 37 psychology students were asked to estimate how long it would take to finish their senior theses. The average estimate was 33.9 days. They also estimated how long it would take "if everything went as well as it possibly could" (averaging 27.4 days) and "if everything went as poorly as it possibly could" (averaging 48.6 days). The average actual completion time was 55.5 days, with about 30% of the students completing their thesis in the amount of time they predicted.[1]

Another study asked students to estimate when they would complete their personal academic projects. Specifically, the researchers asked for estimated times by which the students thought it was 50%, 75%, and 99% probable their personal projects would be done.[5]

- 13% of subjects finished their project by the time they had assigned a 50% probability level;

- 19% finished by the time assigned a 75% probability level;

- 45% finished by the time of their 99% probability level.

A survey of Canadian tax payers, published in 1997, found that they mailed in their tax forms about a week later than they predicted. They had no misconceptions about their past record of getting forms mailed in, but expected that they would get it done more quickly next time.[9] This illustrates a defining feature of the planning fallacy: that people recognize that their past predictions have been over-optimistic, while insisting that their current predictions are realistic.[4]

For group tasks

Carter and colleagues conducted three studies in 2005 that demonstrate empirical support that the planning fallacy also affects predictions concerning group tasks. This research emphasizes the importance of how temporal frames and thoughts of successful completion contribute to the planning fallacy.[10]

Proposed explanations

- Kahneman and Tversky originally explained the fallacy by envisaging that planners focus on the most optimistic scenario for the task, rather than using their full experience of how much time similar tasks require.[4]

- Roger Buehler and colleagues account for the fallacy by examining wishful thinking; in other words, people think tasks will be finished quickly and easily because that is what they want to be the case.[6]

- In a different paper, Buehler and colleagues suggest an explanation in terms of the self-serving bias in how people interpret their past performance. By taking credit for tasks that went well but blaming delays on outside influences, people can discount past evidence of how long a task should take.[6] One experiment found that when people made their predictions anonymously, they do not show the optimistic bias. This suggests that the people make optimistic estimates so as to create a favorable impression with others,[11] which is similar to the concepts outlined in impression management theory.

- Another explanation proposed by Roy and colleagues is that people do not correctly recall the amount of time that similar tasks in the past had taken to complete; instead people systematically underestimate the duration of those past events. Thus, a prediction about future event duration is biased because memory of past event duration is also biased. Roy and colleagues note that this memory bias does not rule out other mechanisms of the planning fallacy.[12]

- Sanna and colleagues examined temporal framing and thinking about success as a contributor to the planning fallacy. They found that when people were induced to think about a deadline as distant (i.e., much time remaining) vs. rapidly approaching (i.e., little time remaining), they made more optimistic predictions and had more thoughts of success. In their final study, they found that the ease of generating thoughts also caused more optimistic predictions.[10]

- One explanation, focalism, proposes that people fall victim to the planning fallacy because they only focus on the future task and do not consider similar tasks of the past that took longer to complete than expected.[13]

- As described by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month, adding new personnel to an already-late project incurs a variety of risks and overhead costs that tend to make it even later; this is known as Brooks's law.

- The "authorization imperative" offers another possible explanation: much of project planning takes place in a context which requires financial approval to proceed with the project, and the planner often has a stake in getting the project approved. This dynamic may lead to a tendency on the part of the planner to deliberately underestimate the project effort required. It is easier to get forgiveness (for overruns) than permission (to commence the project if a realistic effort estimate were provided). Such deliberate underestimation has been named by Jones and Euske "strategic misrepresentation".[14]

- Apart from psychological explanations, the phenomenon of the planning fallacy has also been explained by Taleb as resulting from natural asymmetry and from scaling issues. The asymmetry results from random events giving negative results of delay or cost, not evenly balanced between positive and negative results. The scaling difficulties relate to the observation that consequences of disruptions are not linear, that as size of effort increases the error increases much more as a natural effect of inefficiencies of larger efforts' ability to react, particularly efforts that are not divisible in increments. Additionally this is contrasted with earlier efforts being more commonly on-time (e.g. the Empire State Building, The Crystal Palace, the Golden Gate Bridge) to conclude it indicates inherent flaws in more modern planning systems and modern efforts having hidden fragility. (For example, that modern efforts – being computerized and less localized invisibly – have less insight and control, and more dependencies on transportation.)[15]

- Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner write that planning on government-funded projects is often rushed so that construction can begin as soon as possible to avoid later administrations undoing or cancelling the project. They say a longer planning period tends to result in faster and cheaper construction.[16]

Methods for counteracting

Summarize

Perspective

Segmentation effect

The segmentation effect is defined as the time allocated for a task being significantly smaller than the sum of the time allocated to individual smaller sub-tasks of that task. In a study performed by Forsyth in 2008, this effect was tested to determine if it could be used to reduce the planning fallacy. In three experiments, the segmentation effect was shown to be influential. However, the segmentation effect demands a great deal of cognitive resources and is not very feasible to use in everyday situations.[17]

Implementation intentions

Implementation intentions are concrete plans that accurately show how, when, and where one will act. It has been shown through various experiments that implementation intentions help people become more aware of the overall task and see all possible outcomes. Initially, this actually causes predictions to become even more optimistic. However, it is believed that forming implementation intentions "explicitly recruits willpower" by having the person commit themselves to the completion of the task. Those that had formed implementation intentions during the experiments began work on the task sooner, experienced fewer interruptions, and later predictions had reduced optimistic bias than those who had not. It was also found that the reduction in optimistic bias was mediated by the reduction in interruptions.[3]

Reference class forecasting

Reference class forecasting predicts the outcome of a planned action based on actual outcomes in a reference class of similar actions to that being forecast.

Real-world examples

Summarize

Perspective

The Sydney Opera House was expected to be completed in 1963. A scaled-down version opened in 1973, a decade later. The original cost was estimated at $7 million, but its delayed completion led to a cost of $102 million.[10]

The Eurofighter Typhoon defense project took six years longer than expected, with an overrun cost of 8 billion euros.[10]

The Big Dig which undergrounded the Boston Central Artery was completed seven years later than planned,[18] for $8.08 billion on a budget of $2.8 billion (in 1988 dollars).[19]

The Denver International Airport opened sixteen months later than scheduled, with a total cost of $4.8 billion, over $2 billion more than expected.[20]

The Berlin Brandenburg Airport is another case. After 15 years of planning, construction began in 2006, with the opening planned for October 2011. There were numerous delays. It was finally opened on October 31, 2020. The original budget was €2.83 billion; current projections are close to €10.0 billion.

Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant Unit 3 faced severe delay and a cost overrun. The construction started in 2005 and was expected to be completed by 2009, but completed only in 2023.[21][22] Initially, the estimated cost of the project was around 3 billion euros, but the cost has escalated to approximately 10 billion euros.[23]

California High-Speed Rail is still under construction, with tens of billions of dollars in overruns expected, and connections to major cities postponed until after completion of the rural segment.

The James Webb Space Telescope went over budget by approximately 9 billion dollars, and was sent into orbit 14 years later than its originally planned launch date.

See also

- Downside risk – Risk of the actual return being below the expected return

- Hiding hand principle – How ignorance intersects with rational choice to undertake a project

- Hofstadter's law – Adage referring to time estimates

- Parkinson's law – Adage that work expands to fill its available time

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.