Loading AI tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

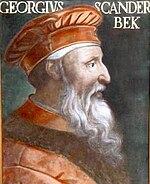

The Myth of Skanderbeg is one of the main constitutive myths of Albanian nationalism.[1][2][3] In the late nineteenth century during the Albanian struggle and the Albanian National Awakening, Skanderbeg became a symbol for the Albanians and he was turned into a national Albanian hero and myth.[4][5][6]

After the death of Skanderbeg, the Arbëresh (Albanians) migrated from the Balkans to southern Italy. There his memory and exploits survived and were maintained among them in their musical repertoire.[7] Skanderbeg was transformed into a nation building myth by Albanian nationalist writers and thus his deeds were transformed into a mixture of facts, half truths and folklore.[8] The Myth of Skanderbeg is the only myth of Albanian nationalism that is based on a person; the others are based on ideas, abstract concepts, and collectivism.[9] The myth of Skanderbeg was not created by Albanian intellectuals but was already part of the Arbereshe folklore and collective memory.[10] According to Oliver Jens Schmitt, "there are two different Skanderbegs today: the historic Skanderbeg, and a mythic national hero as presented in Albanian schools and nationalist intellectuals in Tirana and Pristina."[11]

Skanderbeg is built in part of the antemurale myth complex which portrays Albanians united by Skanderbeg as protectors of the nation and Christendom against "invading Turks".[12] In the 16th century, the "Defence against the Turks" had become a central topic in East Central and South East Europe. It was put in functional use and served as a propaganda tool and to mobilize religious feelings of the population.[13] People who participated in campaigns against the Ottoman Empire were referred to as “antemurale Christianitatis” (the protective wall of Christianity).[14] The Pope Calixtus III gave Skanderbeg the title Athleta Christi, or Champion of Christ.[15] Furthermore, according to Louise Marshall, during the 18th century the Myth of Skanderbeg was moulded and transformed to suit the taste and the anxieties of the British readers.[16]

Under the influence of the Myth of Skanderbeg and antemurale myth, the Albanian Catholic clergy seems to understand the figure of Mother Teresa as Skanderbeg's ideological heir who completes his task of guarding the boundaries of Catholicism and Albanianism, introducing a new era after the end of glorious era that culminated with Skanderbeg.[17][18] In contrast to the Skanderbeg myths of Albanian Christians, the Myth of Skanderbeg of Albania's Muslim community had a positive outcome because the glory of the Illyrian era did not end with Skanderbeg, but continued into the Ottoman era.[19]

Serbian historians, often contradictorily, used Skanderbeg as a symbol of joint Serbian-Albanian progress (1866).[20] On the other hand, forty years later, in a different political environment.[21] Spiridon Gopčević, a proponent of Serbian expansionism in the Ottoman Balkans, claimed that northern Albanians are actually Serbs and Skanderbeg's main motivation was his feelings of Serb national injury.[22]

In Montenegro, a country which had tribal structures similar to the ones in northern Albania and also had a similar mentality, Skanderbeg was celebrated as a hero, a concept which was incorporated into the movement to justify an expansion of Montenegro into northern Albania.[23] By the end of the 19th century, one could find a wide dissemination of brochures with Skanderbeg being presented as a hero along the Montenegro-Albania border.[24] The myth is particularly popular in Kuči tribe.

In Serbian historiography it has been supported that Skanderbeg's great-grandfather, was a nobleman who was granted possession of Kaninë after taking part in Emperor Stefan Dušan's conquests. This reading is based on a mistaken translation by Karl Hopf in the 19th century and has been discredited ever since.[25] It became popular in Serbian propaganda circles again in the 1980s, right before the crisis in Kosovo, where Serb ultra nationalists again celebrated Skanderbeg as "the son of Ivan, Đorđ Kastrioti, the Serbian horseman of Albania."[26] During the 2000s Skanderbeg's origins was a topic on internet chat rooms and that the figure was over time increasingly included into Serbian national narratives, yet still without enough proofs to claim he was Serbian.[27]

The ”featured article” about Skanderbeg in the Serbian-language version of Wikipedia portray Skanderbeg as a Serb.

The wars between the Ottomans and Skanderbeg along with his death resulted in the migration of Albanians to southern Italy and creation of the Arbëresh community (Italo-Albanians).[7] The memory of Skanderbeg and his exploits was maintained and survived among the Arbëresh through songs, in the form of a Skanderbeg cycle.[7] Skanderbeg's fame survived in Christian Europe for centuries, while in largely Islamized Albania it largely faded,[28][29] though his memory was still alive in oral tradition.[30] It was only in the 19th century, in the period of the Albanian National Revival, that Skanderbeg was rediscovered and raised to the level of national mythm for all Albanians.[5][6] During the late nineteenth century the symbolism of Skanderbeg increased in an era of Albania national struggles that turned the medieval figure into a national Albanian hero.[4] The Arbereshe passed their traditions concerning Skanderbeg to Albanian elites outside Italy.[10] Thus, the myth of Skanderbeg was not fabricated by Albanian intellectuals but it was part of the Arbereshe folklore and collective memory.[10] Although Skanderbeg had already been used in the construction of the Albanian national code, especially in communities of Arbėresh, it was only in the final years of the 19th century with the publication of the work of Naim Frashëri "Istori'e Skenderbeut" in 1898 that his figure assumed a new dimension.[31] Naim Frasheri was the biggest inspiration and guide for most Albanian poets and intellectuals.[32]

Albanian nationalists needed an episode from medieval history for the centre of the Albanian nationalistic mythology and they chose Skanderbeg, in the absence of the medieval kingdom or empire.[33] The figure of Skanderbeg was subjected to Albanisation, and he was presented as a national hero.[34] Later books and periodicals continued this theme,[35] and nationalist writers transformed history into myth.[36] The religious aspect of Skanderbeg's struggle against Muslims was minimized by Albanian nationalists because it could divide Albanians and undermine their unity as Albanians are both Muslims and Christians.[37][38] In the late Ottoman period Albanian intellectuals claimed that Skanderbeg had overcome self interest and religious loyalty through service and loyalty toward an Albanian nation, itself absent in the fifteenth century.[39] There was significant effort of the Albanian historiography to adapt the facts about Skanderbeg to meet the requests of the contemporary ideology.[40] Although the Myth of Skanderbeg had little to do with the reality it was incorporated in works about history of Albania.[41] At the height of the Rilindja movement, in 1912, Skanderbeg's flag was raised in Vlorë.[30]

Skanderbeg was a figure featured in 19th century Greek literature.[42] Papadopoulo Vretto published a biography on Skanderbeg and presented him as a defender of Christianity against the Muslim Ottomans and a 'proud Epirotan' descendant of king Pyrrhus of ancient Epirus.[42] The book itself did not claim Skanderbeg as Greek, yet the text became influential in shaping a long tradition within Greek literature that appropriated him as a Greek national hero and patriot.[42] Greek revolutionaries read the book and commemorated his Skanderbeg actions as ones of Greek and Christian pride.[42] At the time as the idea of an Albanian nation consolidated Papadopoulo's book spread to the Arbereshë (Albanian) diaspora of southern Italy and it influenced Italo-Albanian intellectuals who sought to elevate figures such as Skanderbeg as an Albanian hero and differentiate themselves from Greeks.[42]

From the early 2000s, the figure of Skanderbeg and his ethnic background has attracted the attention of Macedonian academia and ethnic Macedonians.[4] The popularity of Skanderbeg and his status as a "national hero" has grown in Macedonia and ideas exist that he had Slavic origins, lived in a Slavic context or was from Tetovo.[43] Skanderbeg has featured in a 2006 novel by philosopher and translator Dragi Mihajlovski that told the narratives of thirteen people and their views of him.[4] Petar Popovski, an essayist wrote a 1200-page book that claimed he located historical evidence of Skanderbeg's ethnic and national Macedonian origins.[4] Popovski also criticised Macedonian authorities for not incorporating Skanderbeg as part of the national Macedonian genealogy.[44] The majority of Macedonian academia rejects such claims over Skanderbeg as not based on historical evidence.[27] During the 2000s Skanderbeg's origins was a topic among Macedonians on internet chat rooms and that the figure was over time being more included into Macedonian national narratives.[27] Rumors also existed in Macedonia that a statue dedicated to Skanderbeg as a "Macedonian junak" might be erected in Prilep by government authorities.[27]

Skanderbeg's name, horse, and sword summarize exploits of his figure:[45]

At the dawn of the 20th century, the figure of Skanderbeg as the Albanian national hero took another dimension through the appearance of pretenders to the throne who claimed his descent.[46] Being aware of the myth of Skanderbeg, many pretenders on the Albanian throne, like the German nobleman Wilhelm of Wied and several European adventurers, named themselves and their descendants after Skanderbeg.[47] Both Zogu and Enver Hoxha presented themselves as heirs of Skanderbeg.[48][49][50][51] One of the important reasons for the regime of Enver Hoxha to emphasize the interest in Skanderbeg's period was to justify the building of a totalitarian dictatorship.[52] Albanian historians intensively mythologized Skanderbeg during communist regime to give legitimacy to the policy of the government.[53]

The main components of various interpretations of the picture of Skanderbeg are still present, except that communist ideological components installed by Hoxha's regime have been replaced by nationalist ones. In some historical and commercial publications, Adem Jashari (1955—1998) is portrayed as the new Albanian national hero in a historical succession of Skanderbeg.[54][55]

Transformation of Skanderbeg into a national symbol served both national cohesion and as an argument for Albania's cultural affinity to Europe because the national narrative of Skanderbeg symbolized the sacrifice of the Albanians in "defending Europe from Asiatic hordes".[56] Pro-European public discourse in modern Albania uses the Myth of Skanderbeg as evidence of Albania's European identity.[57]

As a national hero, Albanian politicians in power have over time promoted the figure of Skanderbeg and he has been revered and acclaimed in oral history.[4] The exploits of Skanderbeg are celebrated as the struggle for freedom from foreign control, ethnic and national Albanian accomplishment, the wisdom of a past Albanian ruler, a figure that transcends multi-ethnic Balkan divisions and a regional contributor to European history.[4] The role of Skanderbeg as a Christian figure that fought against the (Muslim) Ottoman conquest of the continent has been deemphasised over time.[4]

Because of the insufficient primary sources it is difficult to pin down the "hero of the Albanian nation" status of Skanderbeg. Both Albanian communists and Christians have constructed Skanderbeg into a national figure.[58] Contemporary Muslim Albanians deemphasize the (Christian) religious heritage of Skanderbeg by viewing him as a defender of the nation and he is promoted as an Albanian symbol of Europe and the West.[59]

Since Skanderbeg occupies the central place in Albanian national myths, it complicates his critical analysis by the historians.[60] Those who performed a critical analysis of Skanderbeg, as Vienna historian Oliver Jens Schmitt did, would quickly be accused of committing sacrilege and sullying the Albanian national honor.[61][62]

An emphasis on Skanderbeg's struggle and conflict with the Ottomans as a symbol to create a unitary Albanian state has volatile implications because it is not restricted to Albania as was under the government of Hoxha, but encompasses the wider area inhabited by Albanians within the Balkans.[63] The myth of Skanderbeg represents the main ingredient of the debate about future aspirations of the Albanian nation.[64]

Myth of Skanderbeg was included in the program of the following academic conferences:

The key question in scientific research of the Myth of Skanderbeg is not its historical basis, or whether it has one at all, but the investigation of its meanings and purposes.[71]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.