Loading AI tools

Max Henry Ferrars (28 October 1846 – 7 February 1933) was a British colonial officer, author, photographer and university lecturer, mainly active in British Burma and later, in Freiburg, Germany. He served for 25 years in the Imperial East India Forestry Service and other public offices in colonial Burma, today's Myanmar. Together with his wife Bertha, Ferrars wrote and illustrated an extensive ethnographical and photographic study of the native cultures and societies, titled Burma and published in 1900.[1][2] Further, Max and Bertha Ferrars were the grandparents of the British novelist Elizabeth Ferrars.

Max Henry Ferrars | |

|---|---|

| Born | 28 October 1846 Killucan, Ireland |

| Died | 17 February 1933 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Trinity College Dublin |

| Alma mater | Royal Saxon Academy of Forestry, Kingdom of Saxony |

| Occupation(s) | colonial officer, author, photographer and university lecturer |

| Known for | ethnographical accounts and photographs of 19th-century Burma |

| Spouse | Bertha Ferrars |

| Family | Elizabeth Ferrars |

From the 2000s onwards, Ferrars' life and work were primarily recognized by the Royal Geographical Society and the ethnographical museum in Freiburg, to which he had donated a number of Burmese cultural objects.

The 2011 collection on articles on Bamar people at Human Relations Area Files called the book "chiefly remarkable for a wealth of photographs on all topics. These are unequalled in the literature."

Max Henry Ferrars was born on 28 October 1846 in Killucan, Ireland.[3] He was the son of an Irish clergyman and a German mother. After studies at Trinity College Dublin, he moved to Germany in 1870 and specialised in forestry at the Royal Saxon Academy of Forestry in Tharandt, near Dresden.[3][4] This academy, founded by renowned silviculturist Heinrich Cotta, was a leading institution, where forestry management was taught as a scientific discipline, including geometric survey of the forest, land management, biology and economics.[5]

Having completed his education in 1871, Ferrars moved to British Burma, where he first served as Forestry Superintendent in the Imperial East India Forestry Service and later as Inspector of Schools and Superintendent of Educational Services in the British colonial administration.[3][6] Early in the 1850s, the Second Anglo-Burmese War had led to British rule in Lower Burma and the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 resulted in the total annexation of Burma.[7] As Inspector-General of the Indian Forest Service, the German forestry administrator Dietrich Brandis, who is considered to be the founder of tropical forestry, developed a method for determining the commercial value and for sustainable management of teak forests from 1856 onwards.The exploitation and export of timber, including Burma's valuable resources of teak, was an important factor for the colonial economy.[8]

Ferrars was also a member of the Anglo-Oriental Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade in Burma and wrote about the detrimental effects of opium.[9][10] Because of this, he encountered conflicts with the British authorities and had to resign from his positions at the age of 50 in 1896.[11]

Based on their sound knowledge of the Burmese language and wide travels in different parts of the country, he and his wife Bertha Ferrars (née Häusler, 17 November 1845 - 1937) published a book in 1900, entitled Burma. This included detailed ethnographical descriptions of various native ethnic groups and their cultures, with 455 black-and-white photographs, taken during their travels in the 1890s.[1][12]

Through narrative text and documentary photographs, Burma presents chapters on people's cycle of life, from childhood through adolescence to manhood and occupation, as well as further chapters on trades and professions, alien races (including ethnic groups Shan, Karen, Chin, Chimpaw, as well as Chinese, natives of India and Europeans), political history and administration, pageants and frolicks, and ends with age and funeral observances. In the appendices, there are notes on Burmese chronology, language, music, including specimens of Burmese music in Western musical notation, statistics on population, imports and exports, as well as on time and calendar.[13]

Among other observations, the authors took photographs of people at work or during special celebrations, engaged in popular sports, boat races, gambling or the Burmese form of chess.[14] As Wright noted, there is no record about the reasons, why the Ferrars undertook such an ambitious project, nor is there information about their use of photographic technology under the climatic conditions of Burma. The book was printed in a second edition in 1901, and reprinted as facsimile in Bangkok, Thailand, in 1996.[15]

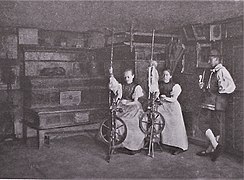

The Ferrars' photographs often show people in their 'natural settings', rather than subjected to studio set-ups and pictorial backdrops, as was the case with many images of Burmese people from this period. In contrast, their photos are almost documentary in style; the images are taken in the village, at a local house or in a shrine. Yet, these images are also constructed; individuals have been asked to pose, although this might have been due to the long exposure times required.

— Joanna Wright, Curator of Picture Library at the Royal Geographical Society

In 1896, the Ferrars returned to Europe and settled in the university town of Freiburg i.Br. on the outskirts of the Black Forest in southern Germany. Max Ferrars joined the advisory committee of the city's Museum for Natural Science and Ethnology (at the time called "Museum für Natur- und Völkerkunde").[16] He offered his knowledge of Burmese culture and donated parts of his collection of cultural objects, thereby becoming one of the museum's first major sponsors. The Ferrars' collection constitutes the main part of the museum's holdings on the culture of today's Myanmar, comprising over 100 items, among them a group of twenty-eight Burmese marionettes, pieces of Burmese lacquerware and parts of the wooden door of a Buddhist monastery.[3]

From 1899 onwards, Ferrars taught English as lecturer at the University of Freiburg's faculty of philology and published textbooks for students of English.[17] Together with German musicologist Hermann Erpf, Ferrars further translated the book on vocal church music A New School of Gregorian Chant by Dominicus Johner from the nearby Beuron Archabbey,[18] first published in 1925 and reprinted in 2007.[19]

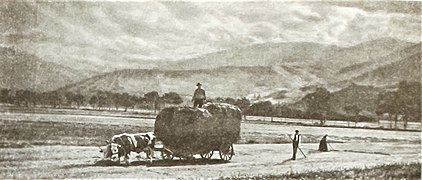

He also continued his travels and photography, as is documented by his photograph of a group of girls in a village in the Black Forest, reprinted in the 1905 book Art in Photography, with selected examples of European and American work.[20][21] Also in 1905, he contributed photographs of the Black Forest region to a book of poems by local writer August Ganther, titled Wälderlüt. In this volume, Ganther's poems in Lower Alemannic dialect are illustrated with thematically appropriate photographs. The poems and pictures deal with the pre-industrial living and working conditions of farmers and their families, for example harvesting in vineyards or hayfields, logging of trees, child labor or burning charcoal.

Further, Ferrars worked at the university's photographic laboratory and won a photography award of the regional railway company in 1911.[22] Already in 1901, he had published a technical and artistic guide on photography, and in November 1926, he was called "a pioneer and innovator of landscape photography" by the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung.[23]

According to the information given on the Freiburg museum's webpage,[3] Ferrars' position as a British university lecturer in Germany became difficult during the years of World War I. Thanks to the university's support, however, he could continue in his teaching position until his official retirement in 1921. Ferrars died on 7 February 1933 in Freiburg,[3] two years after he and his wife had celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary.[24] Their three daughters Bertha, Maximiliana and Marie had been born in Burma, and Marie was the mother of British novelist Elizabeth Ferrars.[25]

In May 1994, a copy of the second edition of the Ferrar's book Burma, with 455 half-tone reproductions after their photographs with a number of albums, loose photographs, lantern slides, autochromes and glass negatives were sold at an auction by Christie's for GBP 1.265,-.[26]

In 2002, Joanna Wright, Curator of Picture Library at the Royal Geographical Society, published the article "Photographs by Max and Bertha Ferrars" from the conference "New Research in the Art and Archaeology of Burma" in order to bring these photographs to the attention of scholars on Burma worldwide. Further research was suggested, "to understand how these images inform us about Burma, and how they form part of Europe's mythologising of Burma."[27]

In 2006, the Geographical Magazine of the Royal Geographical Society in London presented a selection of their images.[28] In a 2013 collection of ethnographic articles on the Bamar[29] and Karen people,[30] the Ferrars' description of these ethnic groups were republished by Human Relations Area Files, founded by Yale University.[31]

In a 2018 article by the Royal Geographical Society's Geographical magazine, titled "The untamed Salween river: Max and Bertha Ferrars, 1890-1899", the author gave credit to the Ferrars' studies and photographs of the Salween river in eastern Myanmar:[32]

During their exploration of Myanmar in the late 1890s, anthropologists Max and Bertha Ferrars documented the geophysical features of the landscapes, as well as the various local populations they encountered along the 2,400km Salween river. [...] The Ferrars discovered that the Salween basin is not only culturally diverse, but also constitutes an area of ecological interest.

— The untamed Salween river: Max and Bertha Ferrars, 1890-1899, Geographical magazine, October, 2018

Photographs in online archive

467 half-plate glass negatives of photographs, taken with a plate camera of the time by the Ferrars, and similar, but not identical to the illustrations in their book on Burma,[33] have been archived by the Royal Geographical Society, London,[34] and more than 300 of them are available online.[35]

British-Burma, ca. 1890s

- Chess players

- Burmese traditional marionettes

- Ethnic Chinese women and girls in Shan State

- Burmese women carrying water

- Travelling with elephants

- Interior of village monastic school

Black Forest, ca. 1896–1905

- Women spinning in farmhouse

- Farmers making hey

- Workers logging trees

- Ferrars, Max; Ferrars, Bertha (1900). Burma. [With 455 illustrations and a map of Burma]. London: Sampson Low Marston & Co. OCLC 560197521.

- Max and Bertha Ferrars: Burma. 2nd ed. (1901), Sampson Low Marston & Co Limited, London, Great Britain (pdf).

- Max and Bertha Ferrars: Burma. (1996) AVA Pub. House, Bangkok, Thailand, ISBN 974-89409-7-7, OCLC 43445823.

- Max Henry Ferrars (1901), Handcamera und Momentphotographie: eine Beschreibung der wichtigsten Verfahren: mit 47 Kunstbeilagen, incl. Heliogravüre und Lichtdruck, und zahlreichen Textilillustrationen (in German), Düsseldorf: Ed. Liesegang's Verlag, pp. XVI, 265 pages

- August Ganther, Max Ferrars (1905), Wälderlüt: Gedichte in niederalemanischer Mundart. Mit 53 Bildern aus dem Schwarzwald von Max Ferrars (in Swiss German), Lahr

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Other important photographers of the 19th century in British Burma:

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.