Loading AI tools

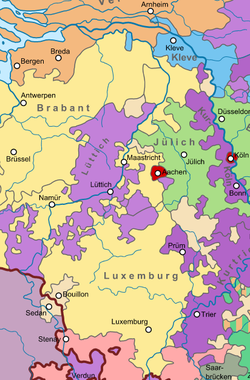

The Luxembourg campaigns were two military campaigns by the Dutch Republic and the Duchy of Bouillon against the Spanish Southern Netherlands during the Eighty Years' War in 1593 and 1595. The first was undertaken by a Dutch States Army commanded by Philip of Nassau to the Duchy of Luxembourg in early 1593, with the aim of distracting the Spanish Army of Flanders to a different part of the Habsburg Netherlands, create confusion and block the importation of new pro-Spanish troops to the Low Countries via the Spanish Road.[3] Other goals were dealing economic damage to Spain, and supporting the Protestant claimant to the French throne Henry of Navarre (later Henry IV) and the Protestant prince of Sedan and duke of Bouillon, Henry de La Tour d'Auvergne.[4]: 249

| Luxembourg campaigns | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War, Henry IV's succession and the Franco-Spanish War (1595–1598) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Dutch at Sankt Vith 1593: 500 infantry[1][2] 1200 cavalry[1][2] | Unknown | ||||||

The first campaign did not result in territorial gains, but did do damage to the Luxembourgish countryside,[4] and successfully managed to distract the Spanish army.[3] Two years later, a similar campaign to Luxembourg led to the temporary occupation of Huy in neutral Liège by the Dutch States in February–March 1595, but they were soon expelled and the Duke of Bouillon was also driven away from Luxemburg's border fortresses again.[5][6]

|

|

| Peter Ernst von Mansfeld, Spanish governor-general 1592–1594. |

Prince Maurice, Dutch captain-general 1589–1625. |

Since 1589, the Dutch States Party had begun to advance in the Netherlands. Under the leadership of Prince Maurice and William Louis, several cities were recaptured from Spanish rule, including Breda (1590), Nijmegen (1591) and Coevorden (1592). The fighting mainly took place beyond the edges of the provinces Holland and Zeeland, the heartland of the rebel States-General of the Netherlands, who proclaimed independence in 1581 and proclaimed the Dutch Republic in 1588. The States-General wanted to relieve the pressure in the Northern Netherlands by attacking the Spaniards further south. Luxembourg was selected as target for this purpose.[3] Another motive was to cause economic damage to Spain and thereby support Henry of Navarre, the Protestant prince who tried to ascend the French throne as King Henry IV, which would give the Protestant-dominated Republic a powerful and religiously aligned ally in the south. Although Henry had already eliminated his rivals during the War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589), the Catholic League (supported by Spain) still refused to recognise him, and kept him outside the French capital, Paris, by military force.[4]: 249

The stadtholder of Luxembourg was Peter Ernst I von Mansfeld-Vorderort, whom Alexander Farnese appointed as the new governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands in December 1592. By attacking Luxembourg, the attention of the new governor-general was particularly targeted. Spanish troops would be sent to reinforce Luxembourg, leaving the Dutch States Army in the Northern Netherlands more space to manoeuvre. Maurice of Nassau, son of the late William the Silent, and captain-general of the Dutch Republic as well as stadtholder of its most important provinces, was responsible for besieging Spanish strongholds in the north, and would benefit from the southern campaign. New Spanish troops also arrived in the Netherlands via the Spanish Road through Luxembourg, so if this southeastern province was controlled by the Dutch Republic, the Spanish troops in the north would be cut off and weakened even further.[3]

The Dutch Republic's plans were supported by the Huguenot Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, French marshall since 1592 and married to Charlotte de La Marck, Duchess of Bouillon and Princess of Sedan (because she died childless in 1594, Henri inherited both lands).[7] Henri sought to expand his duchy's territory.[3] The Duchy of Bouillon bordered on Luxembourg; this gave the Republic a good base. Moreover, the Protestant German princes, who had so far stayed neutral, might be persuaded to join the Dutch side in the war if the Spanish troops were thus weakened.[3]

Preparations

On 14 January 1593, Philip of Nassau departed from Nijmegen via Jülich (whose neutrality had been violated several times before) to Luxemburg with both infantry and cavalry. According to the Journal of Anthonie Duyck 1591–1602 (a detailed journal by an officer in Maurice's army at the time, published by historian Lodewijk Mulder in 1862–1866), Philip had 'a 1000 men on foot' and '11 cornets of cavalry'.[4] It's unclear how many horsemen constituted a 'cornet'. H.M.F. Landolt claimed in Militair woordenboek (1861) that 'a cornet of cavalry [in the 17th century] usually counted 30 to 60 horses; several cornets formed a squadron', which would mean 330 to 660 men on horseback.[8] Duyck reports that a second group of 5 cavalry cornets (circa 150–300 riders) and 'some footsoldiers' departed from Breda and Heusden through southern Brabant to join Philip. They captured Hannut from the Spaniards (Antonio Coquel, Spanish commander during the Siege of Steenwijk (1592), barely escaped capture by fleeing naked), after which the infantry returned to Breda with the prisoners and captured horses, while the cavalry continued the journey and united with Philip's troops.[4] On the other hand, historian Robert Fruin (1861) based his assessment of the events mostly on Book III of contemporary Pieter Christiaenszoon Bor (1595), and claimed the Dutch States Army was composed of '3000 men, both footsoldiers and riders'.[3]

Siege of Sankt Vith

Meanwhile, the Duke of Bouillon had already taken several places in Luxembourg from Spanish hands.[3] Philip marched to Sankt Vith; according to Ardennes historian Michael Bormann (1841), who invoked Tome IV of Jean Bertholet's Histoire ecclésiastique et civile du duché de Luxembourg (1745), Philip had 1200 horsemen and 500 footsoldiers when he attacked the city on 17 January around 7 pm;[1] these figures are confirmed by the Sankt Vither Stadtchronik.[2] Philip attempted to take the city with a certain siege engine which shot burning projectiles into the city, causing fires and panic. The defenders of Sankt Vith however managed to destroy the States' war machine after several hours, and inflicted some casualties upon the beleaguerers.[1] From sunrise until 8 am, Philip assaulted the town again, but to no avail. Thereupon he threatened to exterminate all inhabitants upon conquest if they refused to surrender immediately, but according to Bormann this only strengthened the defenders' resolve to maintain resistance, and a subsequent attack was again repulsed.[1] On the third day, Philip gave up the siege, and instead resorted to plundering the countryside, killing and burning as he went, not sparing the (Catholic) churches.[1]

Plundering of rural Luxembourg

In a letter to raadspensionaris Johan van Oldenbarneveldt, Philip asked if he should join forces with the Duke of Bouillon, to enlarge the campaign. However, they could not count on support from Henry of Navarre. Oldenbarneveldt therefore recalled Philip to the Republic, and ordered him to take brandschattingen (exaction of tributes from populations under the threat of plundering their homes) as loot along the way. Mansfeld was already on his way with a large army, so the Duke of Bouillon withdrew as well.[3] On his way to the city of Luxembourg and back, Duyck reported that 24 villages in the Duchy of Luxembourg were pillaged and burnt, after which Philip returned via Electoral Cologne and Upper Guelders to Nijmegen on 10 February.[4] Duyck therefore remarked that it was more of a 'poaching expedition' to damage the Spaniards than to gain territories. Militarily, the campaign amounted to little, and the losses were insignificant, but there was a 'substantial loot of clothes, linen and some prisoners and hostages to be exchanged for ransom'.[4]

Fall of Geertruidenberg

The first campaign failed to occupy any territories for the Dutch Republic in the south, but did magnage to lure Mansfeld to Luxembourg. The Spanish constructed several cantonments in Liège in the middle of February.[4] This allowed Maurice to encircle Geertruidenberg and he had enough time to construct sconces and prevent Mansfeld's army from relieving the city. Geertruidenberg surrendered to Maurice on 24 June 1593.[4]: 269 After some unsuccessful manoeuvring between States' and Spanish forces around Fort Crèvecoeur and 's-Hertogenbosch in July and August, the Dutch States attempted to supply the Duke of Bouillon with the means to hire mercenaries for a new campaign against Luxembourg, but the money transport was attacked by Spanish cavalry on 17 August south of Lommel, and was forced to retreat.[4]: 273

Meanwhile, Henry of Navarre converted to Catholicism in July 1593 in order to be recognised as the king of France by the Catholic League, allegedly saying: 'Paris is well worth a Mass'. Although he succeeded in this, his Protestant allies in the Dutch Republic fiercely condemned this decision; moreover, they doubted whether Henry was still a reliable military ally. Henry of Navarre declared that he would not abandon the Republic, and continued sending money and troops to combat Spain.[4]: 248–249

Surprise of Eupen

In autumn, Philip of Nassau tried to conquer the fortified city of Limbourg on the river Vesdre. This time he left Nijmegen on 30 October 1593 with 7 cornets (210–420 riders) and 400 footsoldiers, arriving at the walls of Limbourg in the night of 3 November, delayed by heavy rainfall. Because part of the Dutch troops got lost due to rain and darkness, he cancelled the assault, and instead took Eupen by surprise on the next day. The Spanish garrison there fled sought refuge in a church, but Philip ordered his troops to set it on fire. After about 80 Spanish soldiers perished in the flames, the remainder surrendered. The night of 6 November saw Philip return to Nijmegen with the prisoners of war.[4]: 285–286

Henry of Navarre was finally recognised as Henry IV of France when he was crowned in Chartres in February 1594, and held his entry into Paris in March 1594. Maurice conquered Groningen in July 1594, while unpaid Spanish soldiers in Northern France mutinied in August, followed by Italian troops in Brabant; the latter plundered the city of Tienen until their overdue wages were finally fulfilled.[6]

Occupation of Huy

On 17 January 1595, the new French king Henry IV declared war on Spain, ordering duke Henry of Bouillon to launch another campaign through Luxembourg and together with Dutch States forces take the town of Huy in the neutral Prince-Bishopric of Liège. With this 'Protestant' corridor through Catholic territory between the Dutch Republic and Bouillon/Sedan/France, the allies could threaten Brussels and Antwerp. With plenty of violence, Huy was assaulted and captured on 6 February 1595 by Dutch States troops commanded by Charles de Héraugière. After vainly calling on the German Imperial princes to intervene, the Liégeous prince-bishop Ernest of Bavaria requested the new governor-general Fuentes (successor of Ernest of Austria, who unexpectedly died on 20 February 1595[5]) to drive out the Dutch. The Spanish expelled the States' soldiers from Huy on 20 March, and gave back the town to Liège.[6]

Luxembourgish border fortresses recapture

Meanwhile, Francisco Verdugo had followed Fuentes' orders to move from Lingen to the south in order to oust duke Henry of Bouillon from several Luxembourgish fortresses, namely Yvoix (present-day Carignan), La Ferté-sur-Chiers, and Chauvency-le-Château.[5] Although Verdugo received fewer troops from Fuentes than requested, he nevertheless succeeded in reconquering the Luxembourgish border fortresses from the Bouillonese with his small improvised force, before requesting to be discharged around June 1595, and dying in September 1595.[5][6]

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.