Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

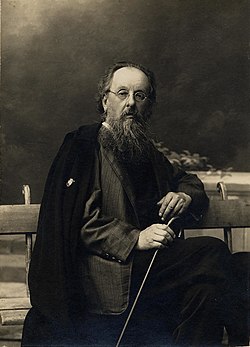

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

Russian scientist (1857–1935) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (/tsjɔːlˈkɔːfski, -ˈkɒf-/;[1] Russian: Константин Эдуардович Циолковский, IPA: [kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj] ⓘ; 17 September [O.S. 5 September] 1857 – 19 September 1935)[2] was a Russian rocket scientist who pioneered astronautics. Along with Hermann Oberth and Robert H. Goddard, he is one of the pioneers of space flight and the founding father of modern rocketry and astronautics.[3][4][5]

His works later inspired Wernher von Braun and leading Soviet rocket engineers Sergei Korolev and Valentin Glushko, who contributed to the success of the Soviet space program. Tsiolkovsky spent most of his life in a log house on the outskirts of Kaluga, about 200 km (120 mi) southwest of Moscow. A recluse by nature, his unusual habits made him appear eccentric to his fellow townsfolk.[6]

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Tsiolkovsky was born in Izhevskoye (now in Spassky District, Ryazan Oblast), in the Russian Empire, to a middle-class family. His father, Makary Edward Erazm Ciołkowski, was a Polish forester of Roman Catholic faith who relocated to Russia.[7] His Russian Orthodox mother Maria Ivanovna Yumasheva was of mixed Volga Tatar and Russian origin.[8][9] According to family tradition, Tsiolkovsky family is of the Zaporozhian Cossack descent, related to Cossack Hetman Nalyvaiko.[10] His father was successively a forester, teacher, and minor government official. At the age of 9, Konstantin caught scarlet fever and lost his hearing.[11]

When he was 13, his mother died.[12] He was not admitted to elementary schools because of his hearing problem, so he was self-taught.[12] As a reclusive home-schooled child, he passed much of his time by reading books and became interested in mathematics and physics. As a teenager, he began to contemplate the possibility of space travel.[2]

Tsiolkovsky spent three years attending a Moscow library,[13][14] where Russian cosmism proponent Nikolai Fyodorov worked. He later came to believe that colonizing space would lead to the perfection of the human species, with immortality and a carefree existence.[14]

Inspired by the fiction of Jules Verne, Tsiolkovsky theorized many aspects of space travel and rocket propulsion. He is considered the father of spaceflight and the first person to conceive the space elevator, becoming inspired in 1895 by the newly constructed Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Despite the youth's growing knowledge of physics, his father was concerned that he would not be able to provide for himself financially as an adult and brought him back home at the age of 19 after learning that he was overworking himself and going hungry. Afterwards, Tsiolkovsky passed the teacher's exam and went to work at a school in Borovsk near Moscow. He met and married his wife Varvara Sokolova during this time. Despite being stuck in Kaluga, a small town far from major learning centers, Tsiolkovsky managed to make scientific discoveries on his own.

The first two decades of the 20th century were marred by personal tragedy. In 1902, Tsiolkovsky's son Ignaty committed suicide. In 1908, many of his accumulated papers were lost in a flood. In 1911, his daughter Lyubov was arrested for engaging in revolutionary activities.

Remove ads

Scientific achievements

Summarize

Perspective

Tsiolkovsky stated that he developed the theory of rocketry only as a supplement to philosophical research on the subject.[15] He wrote more than 400 works including approximately 90 published pieces on space travel and related subjects.[16] Among his works are designs for rockets with steering thrusters, multistage boosters, space stations, airlocks for exiting a spaceship into the vacuum of space, and closed-cycle biological systems to provide food and oxygen for space colonies.

Tsiolkovsky's first scientific study dates back to 1880–1881. He wrote a paper called "Theory of Gases," in which he outlined the basis of the kinetic theory of gases, but after submitting it to the Russian Physico-Chemical Society (RPCS), he was informed that his discoveries had already been made 25 years earlier. Undaunted, he pressed ahead with his second work, "The Mechanics of the Animal Organism". It received favorable feedback, and Tsiolkovsky was made a member of the Society. Tsiolkovsky's main works after 1884 dealt with four major areas: the scientific rationale for the all-metal balloon (airship), streamlined airplanes and trains, hovercraft, and rockets for interplanetary travel.

In 1892, he was transferred to a new teaching post in Kaluga where he continued to experiment. During this period, Tsiolkovsky began working on a problem that would occupy much of his time during the coming years: an attempt to build an all-metal dirigible that could be expanded or shrunk in size.

Tsiolkovsky developed the first aerodynamics laboratory in Russia in his apartment. In 1897, he built the first Russian wind tunnel with an open test section and developed a method of experimentation using it. In 1900, with a grant from the Academy of Sciences, he made a survey using models of the simplest shapes and determined the drag coefficients of the sphere, flat plates, cylinders, cones, and other bodies.

Tsiolkovsky's work in the field of aerodynamics was a source of ideas for Russian scientist Nikolay Zhukovsky, the father of modern aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Tsiolkovsky described the airflow around bodies of different geometric shapes. Because the RPCS did not provide any financial support for this project, he was forced to pay for it largely out of his own pocket.

Tsiolkovsky studied the mechanics of lighter-than-air powered flying machines. He first proposed the idea of an all-metal dirigible and built a model of it. The first printed work on the airship was "A Controllable Metallic Balloon" (1892), in which he gave the scientific and technical rationale for the design of an airship with a metal sheath. Tsiolkovsky was not supported on the airship project, and the author was refused a grant to build the model. An appeal to the General Aviation Staff of the Russian army also had no success.

In 1892, he turned to the new and unexplored field of heavier-than-air aircraft. Tsiolkovsky's idea was to build an airplane with a metal frame. In the article "An Airplane or a Birdlike (Aircraft) Flying Machine" (1894) are descriptions and drawings of a monoplane, which in its appearance and aerodynamics anticipated the design of aircraft that would be constructed 15 to 18 years later. In an Aviation Airplane, the wings have a thick profile with a rounded front edge and the fuselage is faired.

Work on the airplane, as well as on the airship, did not receive recognition from the official representatives of Russian science, and Tsiolkovsky's further research had neither monetary nor moral support. In 1914, he displayed his models of all-metal dirigibles at the Aeronautics Congress in St. Petersburg, but was met with a lukewarm response.

Disappointed at this, Tsiolkovsky gave up on space and aeronautical problems with the onset of World War I and turned his attention to the problem of alleviating poverty. This occupied his time during the war years until the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Starting in 1896, Tsiolkovsky systematically studied the theory of motion of rocket apparatus. Thoughts on the use of the rocket principle in the cosmos were expressed by him as early as 1883, and a rigorous theory of rocket propulsion was developed in 1896. Tsiolkovsky derived the formula, which he called the "formula of aviation", now known as Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, establishing the relationship between:

- change in the rocket's speed ()

- exhaust velocity of the engine ()

- initial () and final () mass of the rocket

After writing out this equation, Tsiolkovsky recorded the date: 10 May 1897. In the same year, the formula for the motion of a body of variable mass was published in the thesis of the Russian mathematician I. V. Meshchersky ("Dynamics of a Point of Variable Mass," I. V. Meshchersky, St. Petersburg, 1897).

His most important work, published in May 1903, was Exploration of Outer Space by Means of Rocket Devices (Russian: Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами).[17] Tsiolkovsky calculated, using the Tsiolkovsky equation,[18]: 1 that the horizontal speed required for a minimal orbit around the Earth is 8,000 m/s (5 miles per second) and that this could be achieved by means of a multistage rocket fueled by liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. In the article "Exploration of Outer Space by Means of Rocket Devices", it was suggested for the first time that a rocket could perform space flight. In this article and its sequels (1911 and 1914), he developed some ideas of missiles and considered the use of liquid rocket engines.

The outward appearance of Tsiolkovsky's spacecraft design, published in 1903, was a basis for modern spaceship design.[19] The design had a hull divided into three main sections.[20] The pilot and copilot would occupy the first section, while the second and third sections held the liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen needed to fuel the spacecraft.[21]

The result of the first publication was not what Tsiolkovsky expected. No foreign scientists appreciated his research, which today is a major scientific discipline. In 1911, he published the second part of the work "Exploration of Outer Space by Means of Rocket Devices". Here Tsiolkovsky evaluated the work needed to overcome the force of gravity, determined the speed needed to propel the device into the Solar System ("escape velocity"), and examined calculation of flight time. The publication of this article made a splash in the scientific world, and Tsiolkovsky found many friends among his fellow scientists.

In 1926–1929, Tsiolkovsky solved the practical problem regarding the role played by rocket fuel in getting to escape velocity and leaving the Earth. He showed that the final speed of the rocket depends on the rate of gas flowing from it and on how the weight of the fuel relates to the weight of the empty rocket.

Tsiolkovsky conceived a number of ideas that have been later used in rockets. They include: gas rudders (graphite) for controlling a rocket's flight and changing the trajectory of its center of mass, the use of components of the fuel to cool the outer shell of the spacecraft (during re-entry to Earth) and the walls of the combustion chamber and nozzle, a pump system for feeding the fuel components, the optimal descent trajectory of the spacecraft while returning from space, etc.[citation needed]

In the field of rocket propellants, Tsiolkovsky studied a large number of different oxidizers and combustible fuels and recommended specific pairings: liquid oxygen and hydrogen, and oxygen with hydrocarbons. Tsiolkovsky did much fruitful work on the creation of the theory of jet aircraft, and invented his chart Gas Turbine Engine.[clarification needed] In 1927, he published the theory and design of a train on an air cushion. He first proposed a "bottom of the retractable body" chassis.[clarification needed]

Space flight and the airship were the main problems to which he devoted his life. Tsiolkovsky had been developing the idea of the hovercraft since 1921, publishing a fundamental paper on it in 1927, entitled "Air Resistance and the Express Train" (Russian: Сопротивление воздуха и скорый по́езд).[22][23] In 1929, Tsiolkovsky proposed the construction of multistage rockets in his book Space Rocket Trains (Russian: Космические ракетные поезда).

Tsiolkovsky championed the idea of the diversity of life in the universe and was the first theorist and advocate of human spaceflight.

Hearing problems did not prevent the scientist from having a good understanding of music, as outlined in his work "The Origin of Music and Its Essence."

Remove ads

Later life

After the October Revolution, the Cheka jailed him in the Lubyanka prison for several weeks.[24]

Still, Tsiolkovsky supported the Bolshevik Revolution, and eager to promote science and technology, the new Soviet government elected him a member of the Socialist Academy in 1918.[18]: 1–2, 8

He worked as a high school mathematics teacher until retiring in 1920 at the age of 63. In 1921, he received a lifetime pension.[18]: 1–2, 8

In his late lifetime, from the mid-1920s onwards, Tsiolkovsky was honored for his pioneering work, and the Soviet state provided financial backing for his research. He was initially popularized in Soviet Russia in 1931–1932 mainly by two writers:[25] Yakov Perelman and Nikolai Rynin. Tsiolkovsky died in Kaluga on 19 September 1935 after undergoing an operation for stomach cancer. He bequeathed his life's work to the Soviet state.[14]

Legacy

Tsiolkovsky influenced later rocket scientists throughout Europe, including Wernher von Braun. Soviet search teams at Peenemünde found a German translation of a book by Tsiolkovsky of which "almost every page...was embellished by von Braun's comments and notes."[18]: 27 Leading Soviet rocket-engine designer Valentin Glushko and rocket designer Sergey Korolev studied Tsiolkovsky's works as youths,[18]: 6–7, 333 and both sought to turn Tsiolkovsky's theories into reality.[18]: 3, 166, 182, 187, 205–206, 208 In particular, Korolev saw traveling to Mars as the more important priority,[18]: 208, 333, 337 until in 1964 he decided to compete with the American Project Apollo for the Moon.[18]: 404

In 1989, Tsiolkovsky was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[26]

Remove ads

Philosophical work

Summarize

Perspective

In 1928, Tsiolkovsky wrote a book called The Will of the Universe: The Unknown Intelligence, in which he propounded a philosophy of panpsychism. He believed humans would eventually colonize the Milky Way galaxy. His thought preceded the Space Age by several decades, and some of what he foresaw in his imagination has come into being since his death.[27] In a letter written in 1911 he indicated his belief that, “Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live in a cradle forever.”[28]

Tsiolkovsky did not believe in traditional religious cosmology, but instead, and to the chagrin of the Soviet authorities, he believed in a cosmic being that governed humans as "marionettes, mechanical puppets, machines, movie characters".[27] He adhered to a mechanical view of the universe, which he believed would be controlled in the millennia to come through the power of human science and industry. In a short article in 1933, he explicitly formulated what was later to be known as the Fermi paradox.[29]

He wrote a few works on ethics, espousing negative utilitarianism.[30]

Remove ads

Tributes

- In 1964, The Monument to the Conquerors of Space was erected to celebrate the achievements of the Soviet people in space exploration. Located in Moscow, the monument is 107 meters (350 feet) tall and covered with titanium cladding. The main part of the monument is a giant obelisk topped by a rocket and resembling in shape the exhaust plume of the rocket. A statue of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the precursor of astronautics, is located in front of the obelisk.

- The State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in Kaluga now bears his name. His residence during the final months of his life (also in Kaluga) was converted into a memorial museum a year after his death.

- The town Uglegorsk in Amur Oblast was renamed Tsiolkovsky by President of Russia Vladimir Putin in 2015.

- The crater Tsiolkovskiy, the most prominent crater on the far side of the Moon, was named after him. Asteroid 1590 Tsiolkovskaja was named after his wife.[31][32] The Soviet Union obtained naming rights by operating Luna 3, the first space device to successfully transmit images of the side of the Moon not seen from Earth.[33]

- The Tsiolkovsky Memorial Apartment. A museum created in Borovsk where he lived and had started his career as a teacher.[34]

- There is a statue of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky directly outside the Sir Thomas Brisbane Planetarium in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- There is a Google Doodle honoring the famous pioneer.[35]

- There is a Tsiolkovsky exhibit on display at the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, California.

- There is a 1 ruble 1987 coin commemorating the 130th anniversary of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky's birth.[36]

Awards and decorations dedicated to Tsiolkovsky

- The USSR Academy of Sciences issued the golden table-top Tsiolkovsky Medal "For outstanding work in the field of interplanetary communications". It was awarded to Sergey Korolev, V.P. Glushko, N.A. Pilyugin, M.V. Keldysh, K.D. Bushuev, Yuri Gagarin, German Titov, A.G. Nikolaev and many other cosmonauts.[37]

- The USSR Cosmonautics Federation issued its own Tsiolkovsky Medal

- The Russian Federal Space Agency («Федеральное космическое агентство») instituted the Tsiolkovsky badge

- After the Federal Space Agency was reformed into the Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities, it replaced the Tsiolkovsky badge with the K.E.Tsiolkovsky badge

Remove ads

In popular culture

- Tsiolkovsky was consulted for the script to the 1936 Soviet science-fiction film, Kosmicheskiy reys.[38]

- The 1968 cult sci-fi film Mars Needs Women concludes with the end credit: " 'Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live in a cradle forever.' -Konstantin Tsiolkovsky."

- Science-fiction writer Alexander Belyaev's novel KETs Star features a city and space station named with Tsiolkovsky's initials.

- The Mars-based space elevators in the Horus Heresy novel Mechanicum by Graham McNeill, set in the Warhammer 40k universe, are called "Tsiolkovsky Towers".[39]

- Episode eight of Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko is called "Tsiolkovsky's Prayer".

- "Tsiolkovski" is the name given to an underground facility in a huge Farside crater on the Moon in Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter’s science-fiction Sunstorm: A Time Odyssey (2005). In the same book the Russian astrophysicist Mikhail Martynov, says: “we Russians have always been drawn to the sun. Tsiolkovski himself, our great space visionary, drew on sun worship in some of his thinking, so it’s said.” Martynov refers to him as „father of Russian astronautics“, and at one time speculates „ No wonder that Tsiolkovski’s vision of humanity’s future in space had been full of sunlight; indeed, he had dreamed that ultimately humankind in space would evolve into a closed, photosynthesizing metabolic unit, needing nothing but sunlight to live. Some philosophers even regarded the whole of the Russian space program as nothing but a modern version of a solar-worshiping ritual.“ (Chap. 42, pp.293-4.)

- In a 2015 episode of Murdoch Mysteries, set in about 1905, James Pendrick works with Tsiolkovsky's daughter to build a suborbital rocket based on his ideas and be the first man in space; a second rocket built to the same design is adapted as a ballistic missile for purposes of extortion.

Remove ads

Works

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Citizens of the Universe” (1933), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Creatures of Higher Levels of Development than Humans” (1933), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Beings of Different Evolutionary Stages of the Universe” (1902), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Is There a God?” (1932), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Are There Spirits?” (1932), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Planets are Inhabited by Living Creatures” (1933), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Cosmic Philosophy” (1935), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Conditional Truth” (1933), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Evaluation of People” (1934), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Non-Resistance or Struggle” (1935), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “Living Beings in the Cosmos” (1895), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Animal of Space” (1929), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Will of the Universe” (1928), (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “On the Moon (На Луне)” (1893).

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices (Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами)” (1903). (PDF), Russian.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices (Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами)” (1914). (PDF), Russian.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices (Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами)” (1926). (PDF), Russian.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Path to the Stars (Путь к звездам)” (1966), Collection of Science Fiction Works, (PDF), English.

- Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin E., “The Call of the Cosmos (Зов Космоса)” (1960), The monograph was first published by the U.S.S.R. Academy of Science Publishing House in 1954 in the second volume of Tsiolkovsky`s Collected Works, (PDF), English.

Remove ads

See also

- Cosmonauts Alley, a Russian monument park where Tsiolkovsky is honored

- History of the internal combustion engine

- Robert Esnault-Pelterie, a Frenchman who independently arrived at Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation

- Russian cosmism

- Russian philosophy

- Soviet space program

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

Citations

General and cited sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads