John Smith (explorer)

English soldier, explorer and writer (1580–1631) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Smith (baptized 6 January 1580 – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, admiral of New England, and author. Following his return to England from a life as a soldier of fortune and as a slave,[1] he played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in North America, in the early 17th century. He was a leader of the Virginia Colony between September 1608 and August 1609, and he led an exploration along the rivers of Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, during which he became the first English explorer to map the Chesapeake Bay area. Later, he explored and mapped the coast of New England. He was knighted for his services to Sigismund Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, and his friend Mózes Székely.

John Smith | |

|---|---|

An illustration of Smith in 1624 | |

| Born | c. 1579 |

| Died | 21 June 1631 (aged 51) London, Kingdom of England |

| Resting place | St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, London |

| Known for | Helping to establish and govern the Jamestown colony Exploration of Chesapeake Bay Exploration and naming of New England English literature |

| Notable work | A Description of New England, Generall Historie of Virginia |

| Signature | |

Jamestown was established on May 14, 1607.[2] Smith trained the first settlers to work at farming and fishing, thus saving the colony from early devastation. He publicly stated, "He that will not work, shall not eat", alluding to 2 Thessalonians 3:10.[3] Harsh weather, a lack of food and water, the surrounding swampy wilderness, and attacks from Native Americans almost destroyed the colony. With Smith's leadership, however, Jamestown survived and eventually flourished. Smith was forced to return to England after being injured by an accidental explosion of gunpowder in a canoe.

Smith's books and maps were important in encouraging and supporting English colonization of the New World. Having named the region of New England, he stated: "Here every man may be master and owner of his owne labour and land. ...If he have nothing but his hands, he may...by industries quickly grow rich."[4] Smith died in London in 1631.

Early life

Smith's exact birth date is unclear. He was baptized on 6 January 1580 at Willoughby,[5] near Alford, Lincolnshire, where his parents rented a farm from Lord Willoughby. He claimed descent from the ancient Smith family of Cuerdley, Lancashire,[6] and was educated at King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth, from 1592 to 1595.[7] Smith was initially set on a path to apprentice with a merchant in the Hanseatic League merchant seaport of King's Lynn in Norfolk.[8][9] However, he found himself ill-suited for the monotonous life of a tradesman and the confines of a counting house.[8][9] Peter Firstbrook, the biographer of John Smith, posits that Smith's brief stint as an apprentice to a merchant in the seaport of King's Lynn sparked his adventurous spirit.[9]

First voyages

Summarize

Perspective

Smith set off to sea at age 16 after his father died. He served as a mercenary in the army of Henry IV of France against the Spaniards, fighting for Dutch independence from King Philip II of Spain. He then went to the Mediterranean Sea, where he engaged in trade and piracy, and later fought against the Ottoman Turks in the Long Turkish War. He was promoted to cavalry captain while fighting for the Austrian Habsburgs in Hungary in the campaign of Michael the Brave in 1600 and 1601.[citation needed]

After the death of Michael the Brave, he fought for Radu Șerban in Wallachia against Ottoman vassal Ieremia Movilă.[10] Smith reputedly killed and beheaded three Ottoman challengers in single combat duels, for which he was knighted by the Prince of Transylvania and given a horse and a coat of arms showing three Turks' heads.[11]

In 1602, he was wounded in a skirmish with the Crimean Tatars, captured, and, taken to a slave market, and then sold.[1] He was sent as an enslaved gift to a woman in Constantinople (Istanbul), Charatza Tragabigzanda, who sent him to perform agricultural work and to be converted to Islam in Rostov. During one of the regular beatings his slavemaster gave him, Smith killed the slavemaster and escaped from Ottoman Empire territory to Muscovy. Smith traveled through the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Europe, and Africa, reaching England in 1604. [12]

Jamestown

Summarize

Perspective

In 1606, Smith became involved with the Virginia Company of London's plan to colonize Virginia for profit, and King James had already granted a charter. The expedition set sail on Discovery, Susan Constant, and Godspeed on 20 December 1606. His page was a 12-year-old boy named Samuel Collier, or "Dutch Samuel".[3]

During the voyage, Smith was charged with mutiny, and Captain Christopher Newport, who was in charge of the three ships, planned to execute him when the expedition stopped in the Canary Islands[13][14] for resupply of water and provisions. Smith was under arrest for most of the trip. However, they landed at Cape Henry on 26 April 1607 and unsealed orders from the Virginia Company designating Smith as one of the leaders of the new colony, which spared him from the gallows.[3][15]

By the summer of 1607, the colonists were still living in temporary housing. The search for a suitable site ended on 14 May 1607 when Captain Edward Maria Wingfield, president of the council, chose the Jamestown site as the location for the colony. After the four month ocean trip, their food stores were sufficient only for each to have a cup or two of grain-meal per day, and someone died almost every day due to swampy conditions and widespread disease. By September, more than 60 had died of the 104 who left England.[16]

In early January 1608, nearly 100 new settlers arrived with Captain Newport on the First Supply, but the village was set on fire through carelessness. That winter, the James River froze over, and the settlers were forced to live in the burned ruins. During this time, they wasted much of the three months that Newport and his crew were in port loading their ships with iron pyrite (fool's gold). Food supplies ran low, although the Native Americans brought some food, and Smith wrote that "more than half of us died".[17] Smith spent the following summer exploring Chesapeake Bay waterways and producing a map that was of great value to Virginia explorers for more than a century.[17]

In October 1608, Newport brought a second shipment of supplies along with 70 new settlers, including the first women. Some German, Polish, and Slovak craftsmen also arrived,[18][19][20][21] but they brought no food supplies. Newport brought a list of counterfeit Virginia Company orders which angered Smith greatly. One of the orders was to crown Indian leader Powhatan emperor and give him a fancy bedstead. The Company wanted Smith to pay for Newport's voyage with pitch, tar, sawed boards, soap ashes, and glass.[16]

After that, Smith tried to obtain food from the local Natives, but it required threats of military force for them to comply.[16] Smith discovered that there were those among both the settlers and the Natives who were planning to take his life, and he was warned about the plan by Pocahontas. He called a meeting and threatened those who were not working "that he that will not work shall not eat." After that, the situation improved and the settlers worked with more industry.[22][23]

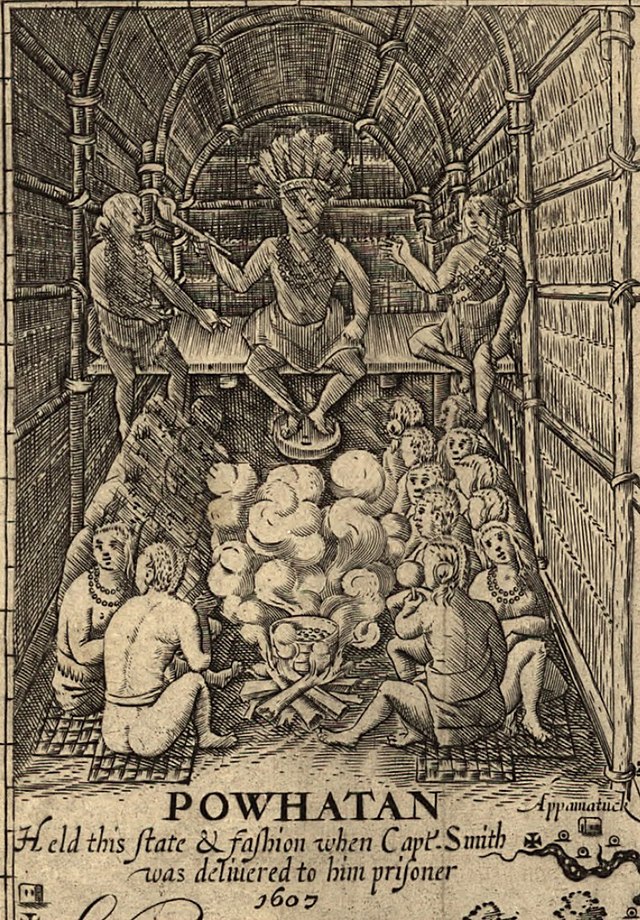

Encounter with Powhatan tribe

In December 1607, Native Americans led by Opechancanough captured Smith while he was seeking food along the Chickahominy River, and he was taken to meet Chief Powhatan, Opechancanough's older brother, at Werowocomoco, the main village of the Powhatan Confederacy. The village was on the north shore of the York River about 15 miles (24 km) north of Jamestown and 25 miles (40 km) downstream from where the river forms from the Pamunkey River and the Mattaponi River at West Point, Virginia.

Smith was removed to the hunters' camp, where Opechancanough and his men feasted him and otherwise treated him like an honoured guest. Protocol demanded that Opechancanough inform Chief Powhatan of Smith's capture, but the paramount chief also was on a hunt and therefore unreachable. Absent interpreters or any other means of effectively interviewing the Englishman, Opechancanough summoned his seven highest-ranking kwiocosuk, or shamans, and convened an elaborate, three-day divining ritual to determine whether Smith's intentions were friendly. Finding it a good time to leave camp, Opechancanough took Smith and went in search of his brother, at one point visiting the Rappahannock tribe who had been attacked by a European ship captain a few years earlier.[24][25]

In 1860, Boston businessman and historian Charles Deane was the first scholar to question specific details of Smith's writings. Smith's version of events is the only source and skepticism has increasingly been expressed about its veracity. One reason for such doubt is that, despite having published two earlier books about Virginia, Smith's earliest surviving account of his rescue by Pocahontas dates from 1616, nearly 10 years later, in a letter entreating Queen Anne to treat Pocahontas with dignity.[26] The time gap in publishing his story raises the possibility that Smith may have exaggerated or invented the event to enhance Pocahontas' image. However, professor Leo Lemay of the University of Delaware points out that Smith's earlier writing was primarily geographical and ethnographic in nature and did not dwell on his personal experiences; hence, there was no reason for him to write down the story until this point.[27]

Henry Brooks Adams attempted to debunk Smith's claims of heroism. He said that Smith's recounting of the story of Pocahontas had been progressively embellished, made up of "falsehoods of an effrontery seldom equaled in modern times". There is consensus among historians that Smith tended to exaggerate, but his account is consistent with the basic facts of his life.[28] Some have suggested that Smith believed that he had been rescued, when he had in fact been involved in a ritual intended to symbolize his death and rebirth as a member of the tribe.[29][30] David A. Price notes in Love and Hate in Jamestown that this is purely speculation, since little is known of Powhatan rituals and there is no evidence for any similar rituals among other Native American tribes.[31] Smith told a similar story in True Travels (1630) of having been rescued by the intervention of a young girl after being captured in 1602 by Turks in Hungary. Karen Kupperman suggests that he "presented those remembered events from decades earlier" when telling the story of Pocahontas.[32] Whatever really happened, the encounter initiated a friendly relationship between the Native Americans and colonists near Jamestown. As the colonists expanded farther, some of the tribes felt that their lands were threatened, and conflicts arose again.

In 1608, Pocahontas saved Smith a second time. Chief Powhatan invited Smith and some other colonists to Werowocomoco on friendly terms, but Pocahontas came to the hut where they were staying and warned them that Powhatan was planning to kill them. They stayed on their guard and the attack never came.[33] Also in 1608, Polish craftsmen were brought to the colony to help it develop. Smith wrote that two Poles rescued him when he was attacked by an Algonquian tribesman.[34]

Chesapeake Bay explorations

In the summer of 1608, Smith left Jamestown to explore the Chesapeake Bay region and search for badly needed food, covering an estimated 3,000 miles (4,800 km). These explorations are commemorated in the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, established in 2006. In his absence, Smith left his friend Matthew Scrivener as governor in his place, a young gentleman adventurer from Sibton Suffolk who was related by marriage to the Wingfield family, but he was not capable of leading the people.[citation needed] Smith was elected president of the local council in September 1608.[22]

Influx of settlers

Some of the settlers eventually wanted Smith to abandon Jamestown, but he refused. Some deserted to the Indian villages, but Powhatan's people also followed Smith's law of "he who works not, eats not". This lasted "till they were near starved indeed", in Smith's words, and they returned home.[3]

In the spring of 1609, Jamestown was beginning to prosper, with many dwellings built, acres of land cleared, and much other work done. Then in April, they experienced an infestation of rats, along with dampness which destroyed all their stored corn. They needed food badly and Smith sent a large group of settlers to fish and others to gather shellfish downriver. They came back without food and were willing enough to take the meager rations offered them. This angered Smith and he ordered them to trade their guns and tools for fruit from the Indians and ordered everyone to work or be banished from the fort.[23]

The weeks-long emergency was relieved by the arrival of an unexpected ship captained by Samuel Argall. He had items of food and wine which Smith bought on credit. Argall also brought news that the Virginia Company of London was being reorganized and was sending more supplies and settlers to Jamestown, along with Lord De la Warr to become the new governor.[23]

In a May 1609 voyage to Virginia, Virginia Company treasurer Sir Thomas Smith arranged for about 500 colonists to come along, including women and children. A fleet of nine ships set sail. One sank in a storm soon after leaving the harbour, and the Sea Venture wrecked on the Bermuda Islands with flotilla admiral Sir George Somers aboard. They finally made their way to Jamestown in May 1610 after building the Deliverance and Patience to take most of the passengers and crew of the Sea Venture off Bermuda, with the new governor Thomas Gates on board.[35]

In August 1609, Smith was quite surprised to see more than 300 new settlers arrive, which did not go well for him. London was sending new settlers with no real planning or logistical support.[3] Then in May 1610, Somers and Gates finally arrived with 150 people from the Sea Venture. Gates soon found that there was not enough food to support all in the colony and decided to abandon Jamestown. As their boats were leaving the Jamestown area, they met a ship carrying the new governor Lord De la Warr, who ordered them back to Jamestown.[3] Somers returned to Bermuda with the Patience to gather more food for Jamestown but died there. The Patience then sailed for England instead of Virginia, captained by his nephew.

Smith was severely injured by a gunpowder explosion in his canoe, and he sailed to England for treatment in mid-October 1609. He never returned to Virginia.[3] Colonists continued to die from various illnesses and disease, with an estimated 150 surviving that winter out of 500 residents. The Virginia Company, however, continued to finance and transport settlers to sustain Jamestown. For the next five years, Governors Gates and Sir Thomas Dale continued to keep strict discipline, with Sir Thomas Smith in London attempting to find skilled craftsmen and other settlers to send.[36]

New England

Summarize

Perspective

In 1614, Smith returned to America in a voyage to the coasts of Maine and Massachusetts Bay. He named the region "New England".[37] The commercial purpose was to take whales for fins and oil and to seek out mines of gold or copper, but both of these proved impractical so the voyage turned to collecting fish and furs to defray the expense.[38] Most of the crew spent their time fishing, while Smith and eight others took a small boat on a coasting expedition during which he traded rifles for 11,000 beaver skins and 100 each of martins and otters.[39]

Smith collected a ship's cargo worth of "Furres… traine Oile and Cor-fish" and returned to England. The expedition's second vessel under the command of Thomas Hunt stayed behind and captured a number of Indians as slaves,[39] including Squanto of the Patuxet. Smith was convinced that Hunt's actions were directed at him; by inflaming the local population, Smith said, he could "prevent that intent I had to make a plantation there", keeping the country in "obscuritie" so that Hunt and a few merchants could monopolize it.[39] According to Smith, Hunt had taken his maps and notes of the area to defeat's Smith's settlement plans.[40] He could not believe that Hunt was driven by greed since there was "little private gaine" to be gotten; Hunt "sold those silly Salvages for Rials of eight."[41]

Smith published a map in 1616 based on the expedition which was the first to bear the label "New England", though the Indian place names were replaced by the names of English cities at the request of Prince Charles.[42] The settlers of Plymouth Colony adopted the name that Smith gave to that area,[42] and other place names on the map survive today, such as the Charles River (marked as The River Charles) and Cape Ann (Cape Anna).

Smith made two attempts in 1614 and 1615 to return to the same coast. On the first trip, a storm dismasted his ship. In the second attempt, he was captured by French pirates off the coast of the Azores. He escaped after weeks of captivity and made his way back to England, where he published an account of his two voyages as A Description of New England. He remained in England for the rest of his life.

Smith compared his experiences in Virginia with his observations of New England and offered a theory of why some English colonial projects had failed. He noted that the French had been able to monopolize trade in a very short time, even in areas nominally under English control. The people inhabiting the coasts from Maine to Cape Cod had "large corne fields, and great troupes of well proportioned people", but the French had obtained everything that they had to offer in trade within six weeks.[43] This was due to the fact that the French had created a great trading network which they could exploit, and the English had not cultivated these relations. Where once there was inter-tribal warfare, the French had created peace in the name of the fur trade. Former enemies such as the Massachuset and the Abenaki "are all friends, and have each trade with other, so farre as they have society on each others frontiers."[44]

Smith believed that it was too late to reverse this reality even with diplomacy, and that what was needed was military force. He suggested that English adventurers should rely on his own experience in wars around the world[45] and his experience in New England where his few men could engage in "silly encounters" without injury or long term hostility.[46] He also compared the experience of the Spaniards in determining how many armed men were necessary to effect Indian compliance.[47]

Death and burial

John Smith died on 21 June 1631 in London. He was buried in 1633 in the south aisle of Saint Sepulchre-without-Newgate Church, Holborn Viaduct, London. The church is the largest parish church in the City of London, dating from 1137. Captain Smith is commemorated in the south wall of the church by a stained glass window.[48]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

New Hampshire

The Captain John Smith Monument currently lies in disrepair off the coast of New Hampshire on Star Island, part of the Isles of Shoals. The original monument was built in 1864 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Smith's visit to what he named Smith's Isles. It was a series of square granite slabs atop one another, with a small granite pillar at the top (see adjacent image). The pillar featured three carved faces, representing the severed heads of three Turks that Smith lopped off in combat during his stint as a soldier in Transylvania.[49]

In 1914, the New Hampshire Society of Colonial Wars partially restored and rededicated the monument for the 300th anniversary celebration of his visit.[50] The monument had weathered so badly in the harsh coastal winters that the inscription in the granite had worn away.[51][better source needed] Contemporary newspapers reported dedication of "a bronze tablet" honouring Smith, and dedication of the Tucke Monument.[52]

In 2014, a new monument honouring Smith was dedicated at Rye Harbor State Park, an 18-ton obelisk measuring "16 feet 14 inches (5.23 m)"—in commemoration of the year 1614; 17 feet 2 inches (5.23 m)—in height.[53][54]

Credibility as an author

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2019) |

Many critics judge Smith's character and credibility as an author based solely on his description of Pocahontas saving his life from the hand of Powhatan. Most of the scepticism results from the differences between his narratives. His earliest text is A True Relation of Virginia, submitted for publication in 1608, the year after his experiences in Jamestown. The second was The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, which was published in 1624. The publication of letters, journals, and pamphlets from the colonists was regulated by the companies that sponsored the voyage, in that the communications must go "directly to the company" because no one was to "write any letter of anything that may discourage others". Smith violated this regulation by first publishing A True Relation as an unknown author.[55] Leo Lemay theorizes that the editor of The Generall Historie might have cut out "references to the Indians' hostility, to bickering among the leaders of Virginia Company, and to the early supposed mutiny" of Smith on the voyage to Virginia.[56]

The Pocahontas episode is subject to the most scrutiny by critics, for it is missing from A True Relation but it does appear in The Generall Historie. According to Lemay, important evidence of Smith's credibility is the fact that "no one in Smith's day ever expressed doubt" about the story's veracity, and many people who would have known the truth "were in London in 1616 when Smith publicised the story in a letter to the queen", including Pocahontas herself.[57]

Smith focuses heavily on Indians in all of his works concerning the New World. His relationship with the Powhatan tribe was an important factor in preserving the Jamestown colony from sharing the presumed fate of the Roanoke Colony.

Realizing that the very existence of the colony depended on peace, he never thought of trying to exterminate the natives. Only after his departure were there bitter wars and massacres, the natural results of a more hostile policy. In his writings, Smith reveals the attitudes behind his actions.

— William Randel[58]

Promoter of North American colonization

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2019) |

One of Smith's main incentives in writing about his New World experiences and observances was to promote English colonization. Lemay claims that many promotional writers sugar-coated their depictions of America in order to heighten its appeal, but he argues that Smith was not one to exaggerate the facts. He argues that Smith was very straightforward with his readers about both the dangers and the possibilities of colonization. Instead of proclaiming that there was an abundance of gold in the New World, as many writers did, Smith illustrated that there was abundant monetary opportunity in the form of industry.[59] Lemay argues that no motive except wealth would attract potential colonists away from "their ease and humours at home".[60] "Therefore, he presented in his writings actual industries that could yield significant capital within the New World: fishing, farming, shipbuilding, and fur trading".[61]

Smith insists, however, that only hard workers would be able to reap the benefits of wealth which the New World afforded. He did not understate the dangers and toil associated with colonization. He declared that only those with a strong work ethic would be able to "live and succeed in America" in the face of such dangers.[62]

Additional works

A Map of Virginia is focused centrally on the observations that Smith made about the Native Americans, particularly regarding their religion and government. This specific focus would have been Smith's way of adapting to the New World by assimilating the best parts of their culture and incorporating them into the colony. A Map of Virginia was not just a pamphlet discussing the observations that Smith made, but also a map which Smith had drawn himself, to help make the Americas seem more domestic. As Lemay remarks, "maps tamed the unknown, reduced it to civilisation and harnessed it for Western consciousness," promoting Smith's central theme of encouraging the settlement of America.[63] Many "naysayers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century" have made the argument that Smith's maps were not reliable because he "lacked a formal education in cartography".[64] That allegation, however, was proved false by the fact that Smith was a "master in his chosen fields of experience".[64]

The Proceedings of the English Colony In Virginia was a compilation of other writings; it narrates the colony's history from December 1609 to the summer of 1610, and Smith left the colony in October 1609 due to a gunpowder accident. The writing style of The Proceedings is thought to be better constructed than A Map of Virginia.[65]

In popular culture

Summarize

Perspective

John Smith was honoured on two of the three stamps of the Jamestown Exposition Issue held 26 April – 1 December 1907 at Norfolk, Virginia to commemorate the founding of the Jamestown settlement. The 1-cent John Smith, inspired by the Simon de Passe engraving of the explorer was used for the 1-cent postcard rate. The 2-cent Jamestown landing stamp paid the first-class domestic rate.[66]

John Smith; 1907 issue |

Jamestown landing; 1907 issue |

Captain Smith has featured in popular media several times during the 20th and 21st century.

- Smith was portrayed by Anthony Dexter in the 1953 independent low-budget film Captain John Smith and Pocahontas.[67]

- A fictionalized version of Smith appears in James A. Michener's 1978 novel Chesapeake.[68]

- Smith is one of the main characters in Disney's 1995 animated film Pocahontas and its 1998 straight-to-video sequel Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World. He is voiced by Mel Gibson in the first movie and by his younger brother Donal Gibson in the sequel.[69][70]

- Smith and Pocahontas are central characters in the 2005 Terrence Malick film The New World, in which he was portrayed by Colin Farrell.[71]

- Country singer Blake Shelton played the Disney version in an unaired "Cut for Time" sketch on Saturday Night Live.[72]

- In A Different Flesh by Harry Turtledove, an anthology set in an alternate timeline where the New World is inhabited by Homo erectus and Pleistocene megafauna, John Smith is mentioned as having been killed by 'sims' shortly after the establishment of Jamestown in Virginia.[citation needed]

Publications

Summarize

Perspective

John Smith published eight volumes during his life. The following lists the first edition of each volume and the pages on which it is reprinted in Arber 1910:

- A true relation of such occurrences and accidents of noate as hath hapned in Virginia since the first planting of that collony, which is now resident in the south part thereof, till the last returne from thence. London: Printed for Iohn Tappe, and are to bee solde at the Greyhound in Paules-Church-yard, by W.W. 1608. Quarto. Arber 1910, pp. I:1–40. First attributed to "a Gentleman of the said Collony." then to "Th. Watson" and finally (in 1615) to Smith.[73] A digitized version is hosted at Project Jamestown. Another was prepared for the etext library of the University of Virginia.

- A map of Virginia: VVith a description of the countrey, the commodities, people, government and religion. VVritten by Captaine Smith, sometimes governour of the countrey. Whereunto is annexed the proceedings of those colonies, since their first departure from England, with the discourses, orations, and relations of the salvages, and the accidents that befell them in all their iournies and discoveries. Taken faithfully as they were written out of the writings of Doctor Russell. Tho. Studley. Anas Todkill. Ieffra Abot. Richard Wiefin. Will. Phettiplace. Nathaniel Povvell. Richard Pots. And the relations of divers other diligent observers there present then, and now many of them in England. Oxford: Printed by Joseph Barnes. 1612. Quarto. Arber 1910, pp. I:41–174 Edited by W[illiam] S[immonds]. An abridged edition was printed in Purchas 1625, pp. IV:1691–1704.

- A description of New England: or The obseruations, and discoueries, of Captain Iohn Smith (admirall of that country) in the north of America, in the year of our Lord 1614: with the successe of sixe ships, that went the next yeare 1615; and the accidents befell him among the French men of warre: with the proofe of the present benefit this countrey affoords: whither this present yeare, 1616, eight voluntary ships are gone to make further tryall. London: Printed by Humfrey Lownes, for Robert Clerke. 1616. Quarto. Arber 1910, pp. I:175–232 This volume was translated into German and published in Frankfurt in 1617.[73] A digitized copy is hosted by the Digital Commons of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

- Nevv Englands trials: Declaring the successe of 26. ships employed thither within these sixe yeares: with the benefit of that countrey by sea and land: and how to build threescore sayle of good ships, to make a little navie royall. London: Printed by VVilliam Iones. 1620. Quarto. Arber 1910, pp. I:233–248. This volume contained some of the material from A Description of New-England. A new and somewhat expanded "second edition" was printed in 1622, also by William Jones.[74] Arber 1910, pp. I:249–272

- The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer isles: with the names of the Adventurers, Planters, and Governours from their first beginning, Ano: 1584, to this present 1624. With the Proceedings of those Severall Colonies and the Accidents that befell them in all their Journyes and Discoveries. Also the Maps and Descriptions of all those Countryes, their Commodities, people, Government, Customes, and Religion yet knowne. Divided into sixe Bookes. London: Printed by I.D. and I.H. for Michael Sparkes. 1624. Folio. Arber 1910, pp. I:273–38, II:385–784. The work was republished in 1726, 1727 and 1732.[73]

- An accidence or The path-way to experience: Necessary for all young sea-men, or those that are desirous to goe to sea, briefly shewing the phrases, offices, and words of command, belonging to the building, ridging, and sayling, a man of warre; and how to manage a fight at sea. Together with the charge and duty of every officer, and their shares: also the names, vveight, charge, shot, and powder, of all sorts of great ordnance. With the vse of the petty tally. London: Printed [by Nicholas Okes] for Ionas Man, and Benjamin Fisher. 1626. Octavo. Arber 1910, pp. II:785–804. In the following year the work was enlarged probably by another hand[75] as A sea grammar: vvith the plaine exposition of Smiths Accidence for young sea-men, enlarged. Diuided into fifteene chapters: what they are you may partly conceiue by the contents. London: Printed by Iohn Hauiland. 1627. That same year another printing of An Accidence was also made for Jonas Man and Benjamin Fisher. In 1653 this work, under the title A Sea Grammar, was entirely recast and substantially enlarged by "B.F."[76]

- The true travels, adventures, and observations of Captaine Iohn Smith, in Europe, Asia, Affrica, and America from Anno Domini 1593 to 1629: his accidents and sea-fights in the Straights: his service and strategems of warre in Hungaria, Transilvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia, against the Turks, and Tartars: his three single combats betwixt the Christian Armie and the Turks : after how he taken prisoner by the Turks, sold for a slave, sent into Tartarias: his description of the Tartars, their strange manners and customes of religions, diets, buildings, warres, feasts, ceremonies, and living: how hee flew the Bashaw of Nalbrits in Cambia, and escaped from the Turkes and Tatars: together with a continuation of his Generall history of Virginia, Summer-Iles, New England, and their proceedings, since 1624 to this present 1629: as also of the new plantations of the great river of the Amazons, the iles of St. Christopher, Mevis, and Barbados in the West Indies / all written by actuall authors, whose names you shall finde along the history. London: Printed by J.H. for Thomas Slater. 1630. Folio. Arber 1910, pp. II:805–916. Five years before the publication a shorter version of this autobiography was published in Purchas 1625, pp. II:1361–1370 in a chapter entitled "The Trauels and Aduentures of Captaine IOHN SMITH in diuers parts of the world, begun about the yeere 1596."

- Advertisements for the unexperienced planters of New-England, or any where, or, The path-way to experience to erect a plantation: with the yearely proceedings of this country in fishing and planting, since the yeare 1614. to the yeare 1630. and their present estate: also how to prevent the greatest inconveniences, by their proceedings in Virginia, and other plantations, by approved examples : with the countries armes, a description of the coast, harbours, habitations, land-markes, latitude and longitude: with the map, allowed by our royall King Charles. London: Printed by I. Havilland. 1631. Quarto. Arber 1910, pp. II:917–966.

See also

- Jamestown Exposition

- New Hampshire historical marker no. 18: Isles of Shoals

- Southern Colonies

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.