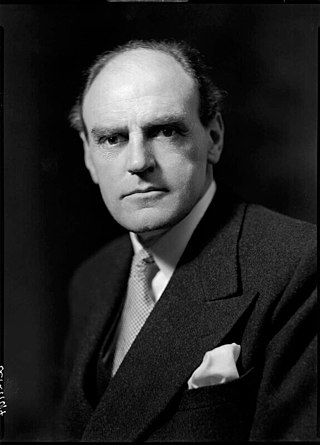

John Reith, 1st Baron Reith

British broadcasting executive and politician (1889–1971) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Charles Walsham Reith, 1st Baron Reith (/ˈriːθ/; 20 July 1889 – 16 June 1971) was a Scottish broadcasting executive who established the tradition of independent public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom. In 1922, he was employed by the BBC, then the British Broadcasting Company Ltd., as its general manager; in 1923 he became its managing director, and in 1927 he was employed as the Director-General of the British Broadcasting Corporation created under a royal charter. His concept of broadcasting as a way of educating the masses marked for a long time the BBC and similar organisations around the world. An engineer by profession, and standing at 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) tall, he was a larger-than-life figure who was a pioneer in his field.[1]

The Lord Reith | |

|---|---|

Reith in 1934 | |

| 1st Director-General of the BBC | |

| In office 1 January 1927 – 30 June 1938 | |

| Monarchs | George V Edward VIII George VI |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Ogilvie |

| Minister of Information | |

| In office 5 January 1940 – 12 May 1940 | |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Hugh Macmillan |

| Succeeded by | Duff Cooper |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Charles Walsham Reith 20 July 1889 Stonehaven, Kincardineshire, Scotland |

| Died | 16 June 1971 (aged 81) Stockbridge, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Resting place | Rothiemurchus chapel, Aviemore, Inverness-shire, Scotland |

| Spouse |

Muriel Reith (m. 1921) |

| Children | 2, including Marista |

| Occupation |

|

The BBC's Reith Lectures were instituted in his honour. The BBC's 'Reith' font is named after him.

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Born at Stonehaven, Kincardineshire,[2] Reith was the fifth son and the youngest, by ten years, of the seven children of the Rev. George Reith, a Scottish Presbyterian minister of the College Church at Glasgow and later Moderator of the United Free Church of Scotland. He was to carry strict Presbyterian religious convictions forward into his adult life. Reith was educated at the Glasgow Academy then at Gresham's School, Holt, Norfolk.[3] He spent two years at the Royal Technical College at Glasgow (later the University of Strathclyde) followed by an apprenticeship as an engineer at the North British Locomotive Company. During this time, he joined the Territorials and in February 1911 was commissioned as an officer in the Scottish Rifles’ 5th Territorial Battalion. In 1913, he moved to London after obtaining a post at S. Pearson and Son through Ernest William Moir, and worked on their construction of the Royal Albert Dock.[1]

Reith, who was 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) tall, joined up with the 5th Scottish Rifles early in the First World War and was quickly transferred to the Royal Engineers as a lieutenant. In October 1915, while fighting in France, he was severely wounded by a sniper's bullet through his left cheek, which nearly cost him his life and left him with a noticeable scar.[1] While lying wounded on a stretcher after the shot, he is reported to have muttered "I'm very angry and I've spoilt a new tunic."[4]

During Reith's convalescence, E W Moir referred him to a post at Pearson's project constructing the cordite factory HM Factory Gretna, comprising the fixing of contracts, estimating of costs, taking out quantities, and inspection of materials. In February 1916, he went to work at Remington Arms, Eddystone, Delaware County, Pennsylvania who were manufacturing the Pattern 1914 Enfield Mk 1 rifle for the British government. He spent the next two years in the United States, supervising armament contracts, and became attracted to the country.[5] He was promoted to captain in 1917, before being transferred to the Royal Marine Engineers in 1918 as a major. He returned to the Royal Engineers as a captain in 1919.

Reith resigned his Territorial Army commission in 1921. He returned to Glasgow as general manager of an engineering firm. In 1922, he returned to London, where he started working as secretary to the London Conservative group of MPs in the 1922 general election. That election's results were the first to be broadcast on the radio.

British Broadcasting Company

Summarize

Perspective

Reith had no broadcasting experience when he replied to an advertisement in The Morning Post for a general manager for an as-yet unformed British Broadcasting Company in 1922. He later admitted that he felt he possessed the credentials necessary to "manage any company".[6] He managed to retrieve his original application from a post box after re-thinking his approach, guessing that his Aberdonian background would carry more favour with Sir William Noble, the Chairman of the Broadcasting Committee.[6]

In his new role, he was, in his own words, "confronted with problems of which I had no experience: Copyright and performing rights; Marconi patents; associations of concert artists, authors, playwrights, composers, music publishers, theatre managers, wireless manufacturers."[5]

The general strike

In 1926, Reith came into conflict with the government during the 1926 general strike. The BBC bulletins reported, without comment, all sides in the dispute, including the Trades Union Congress's and of union leaders. Reith attempted to arrange a broadcast by the opposition Labour Party but it was vetoed by the government, and he had to refuse a request to allow a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to put the case for the miners and other workers.

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin made a national broadcast about the strike from Reith's house and was coached by Reith. When Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, asked to make a broadcast in reply, Reith supported the request. However, Baldwin was "quite against MacDonald broadcasting" and Reith unhappily refused the request.[8] MacDonald complained that the BBC was "biased" and was "misleading the public" while other Labour Party figures were just as critical. Philip Snowden, the former Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, was one of those who wrote to the Radio Times to complain.

Reith's reply also appeared in the Radio Times, admitting the BBC had not had complete liberty to do as it wanted. He recognised that at a time of emergency the government was never going to give the company complete independence, and he appealed to Snowden to understand the constraints he had been under.

- "We do not believe that any other Government, even one of which Mr Snowden was a member, would have allowed the broadcasting authority under its control greater freedom than was enjoyed by the BBC during the crisis."[9]

The Labour leadership was not the only high-profile body denied a chance to comment on the strike. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, wanted to broadcast a "peace appeal" drawn up by church leaders which called for an immediate end to the strike, renewal of government subsidies to the coal industry and no cuts in miners' wages.

Davidson telephoned Reith about his idea on 7 May, saying he had spoken to Baldwin, who had said he would not stop the broadcast, but would prefer it not to happen.[10] Reith later wrote: "A nice position for me to be in between Premier and Primate, bound mightily to vex one or other."[10]

Reith asked for the government view and was advised not to allow the broadcast because, it was suspected, that would give the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, an excuse to commandeer the BBC. Churchill had already lobbied Baldwin to that effect.[11] Reith contacted the Archbishop to turn him down and explain that he feared if the talk went ahead, the government might take the company over.

Although Churchill wanted to commandeer the BBC to use it "to the best possible advantage", Reith wrote that Baldwin's government wanted to be able to say "that they did not commandeer [the BBC], but they know that they can trust us not to be really impartial".[8]

Reith admitted to his staff that he regretted the lack of TUC and Labour voices on the airwaves. Many commentators[who?] have seen Reith's stance during that period as pivotal in establishing the state broadcaster's enduring reputation for impartiality.[11]

After the strike ended, the BBC's Programme Correspondence Department analysed the reaction to the coverage, and reported that 3,696 people complimented the BBC and 176 were critical.[12]

British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Company was part-share owned by a committee of members of the wireless industry, including British Thomson-Houston, The General Electric Company, Marconi and Metropolitan-Vickers. However, Reith had been in favour of the company being taken into public ownership, as he felt that despite the boards under which he had served so far, allowing him a high degree of latitude on all matters, not all future members might do so.[6] Although opposed by some, including members of the Government, the BBC became a corporation in 1927. Reith was knighted the same year.

Reith's autocratic approach became the stuff of BBC legend. His preferred approach was one of benevolent dictator, but with built-in checks to his power. Throughout his life, Reith remained convinced that that approach was the best way to run an organisation. Later Director-General Greg Dyke, profiling Reith in 2007, noted that the term Reithian has entered the dictionary to denote a style of management, particularly with relation to broadcasting.[13] Reith summarised the BBC's purpose in three words: inform, educate, entertain; this remains part of the organisation's mission statement to this day.[14] It has also been adopted by broadcasters throughout the world, notably the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States.

Reith earned a reputation for prudishness in sexual matters. There is an old BBC legend that he once caught an announcer kissing a secretary and decreed that in future the announcer must not read the late-night religious programme The Epilogue. In fact, this may have been inspired by his catching the Chief Engineer, Peter Eckersley, not just kissing but being in flagrante with an actress on a studio table.

He was to be somewhat embarrassed when one of his staff ran off with the quite new wife of the then rising young writer Evelyn Waugh. Reith also had to deal with Eckersley after the BBC Chief Engineer had a rather public affair with a married woman on the staff. Up to the Second World War any member of BBC staff involved in a divorce could lose their job.

Under Reith, the BBC did not broadcast on Sunday before 12:30 PM, to give listeners time to attend church, and for the rest of the day broadcast only religious services, classical music and other non-frivolous programming. European commercial stations Radio Normandie and Radio Luxembourg competed with the BBC on "Reith Sunday" and other days of the week by broadcasting more popular music.[15]

Abdication broadcast

In 1936, Reith directly oversaw the abdication broadcast of Edward VIII. By then his style had become well-established in the public eye. He personally introduced the ex-King (as 'Prince Edward'), before standing aside to allow Edward to take the chair. Doing so, Edward accidentally knocked the table leg with his foot, which was picked up by the microphone. Reith later noted in an interview with Malcolm Muggeridge that some headlines interpreted that as Reith "slamming the door" in disgust before Edward began broadcasting.[16]

Departure

By 1938, Reith had become discontented with his role as Director-General, asserting in his autobiography that the organisational structure of the BBC, which he had created, had left him with insufficient work to do. He was invited by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to become chairman of Imperial Airways, the country's most important airline and one which had fallen into public disfavour because of its inefficiency. Some commentators[17] have suggested a conspiracy amongst the Board of Governors to remove Reith, but that has never been proved, and there is no record of such a thing in Reith's own memoir.[18]

He left Broadcasting House with no ceremony (at his request) but in tears. That evening, he attended a dinner party before driving out to Droitwich to close down a transmitter personally. He signed the visitor's book "J.C.W. Reith, late BBC."[19][20] John Gunther wrote that Reith's "modernist citadel on Portland Place was more important in the life of Britain than most government offices [and] rules the B.B.C. with a hand of granite". He "made the B.B.C. an expression of his nonconformist conscience, and also what is probably the finest broadcasting organization in the world"; Gunther predicted that he "is almost certain to have a big political job some day".[21]

"Reithianism"

The term "Reithianism" describes certain principles of broadcasting associated with Lord Reith. These include an equal consideration of all viewpoints, probity, universality and a commitment to public service. Audiences had little choice apart from the upscale programming of the BBC, a government agency which had a monopoly on broadcasting. Reith, an intensely moralistic executive, was in full charge. His goal was to broadcast, "All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement.... The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance."[22]

Reith succeeded in building a high wall against an American-style free-for-all in radio in which the goal was to attract the largest audiences and thereby secure the greatest advertising revenue. There was no paid advertising on the BBC; all the revenue came from a tax on receiving sets. Highbrow audiences greatly enjoyed it.[23] At a time when American, Australian and Canadian stations were drawing huge audiences cheering for their local teams with the broadcast of baseball, rugby and hockey, the BBC emphasised service for a national, rather than a regional audience. Boat races were well covered along with tennis and horse racing, but the BBC was reluctant to spend its severely limited air time on long football or cricket matches, regardless of their popularity.[24]

Second World War

Summarize

Perspective

In 1940, Reith was appointed Minister of Information in Chamberlain's government. So as to perform his full duties, he became a member of parliament (MP) for Southampton. When Chamberlain fell, Churchill became Prime Minister and moved Reith to the Ministry of Transport. Reith was subsequently moved to become First Commissioner of Works which he held for the next two years, through two restructurings of the job, and was also transferred to the House of Lords by being created Baron Reith.

During that period, the city centres of Coventry, Plymouth and Portsmouth were destroyed by German bombing. Reith urged the local authorities to begin planning postwar reconstruction. He was dismissed from his government post at a very difficult time for Churchill in 1942, following the loss of Singapore. Pressured by Tory backbenchers who wanted a Conservative in the Information role, Reith was replaced by Duff Cooper.

It has been claimed that the sacking was due to Reith being difficult to work with. However, given the absence of direct contact between the two men during Reith's period in several ministerial positions, this is unlikely to be the true reason. More plausible, is the explanation given above, and the cleavage between Reithian management methods: energetic, thorough and highly organised, and the established style of the British civil service at that time: at best, calm and deliberative; at worst, ponderously slow.

Reith also frequently references in his autobiography departmental jealousies resulting from his ministerial activities, reported to him by colleagues such as Sir John Anderson, wartime Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Churchill coalition. Complaints to the latter from fellow ministers and MPs would appear to be the more likely cause of his fall. This came at a crucial stage in Reith's career. After the outbreak of war, several major figures had told Reith that he would soon join the War Cabinet itself, not least Beaverbrook, one of the Prime Minister's closest associates.

Reith's animosity towards Churchill continued. When offered the post of Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (a position he had long coveted), he could not bring himself to accept it, noting in his diary: "Invitation from that bloody shit Churchill to be Lord High Commissioner."[25]

He took a naval commission as a lieutenant of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) on the staff of the Rear-Admiral Coastal Services. In 1943, he was promoted to captain (RNVR), and appointed Director of the Combined Operations Material Department at the Admiralty, a post he held until early 1945.

Post-war

In 1946, he was appointed chairman of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Board, a post he held until 1950. He was then appointed chairman of the Colonial Development Corporation which he held until 1959. In 1948, he was also appointed the chairman of the National Film Finance Corporation, an office he held until 1951.

The BBC's Reith Lectures were instituted in 1948 in his honour. These annual radio talks, with the aim of advancing "public understanding and debate about significant issues of contemporary interest"[26] have been held every year since, with the exception of 1992.

The Independent Television Authority was created on 30 July 1954 ending the BBC's broadcasting monopoly. Lord Reith did not approve of its creation. Speaking at the Opposition despatch box in the House of Lords, he stated:

Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting ... Need we be ashamed of moral values, or of intellectual and ethical objectives? It is these that are here and now at stake.[27]

Later years

Summarize

Perspective

In 1960, Reith returned to the BBC for an interview with John Freeman in the television series Face to Face. When he visited the BBC to record the programme, work was being undertaken, and Reith noticed with dismay the "girlie" pin-ups of the workmen. However, one picture was of a Henry Moore sculpture. "A Third Programme carpenter, forsooth," he growled.[28]

In the interview, he expressed his disappointment at not being "fully stretched" in his life, especially after leaving the BBC. He claimed that he could have done more than Churchill gave him to do during the war. He also disclosed an abiding dissatisfaction with his life in general. He admitted not realising soon enough that "life is for living," and suggested he perhaps still did not acknowledge that fact. He also stated that since his departure as Director-General, he had watched almost no television and listened to virtually no radio. "When I leave a thing, I leave it," he said.[6]

In his later years, he also held directorships at the Phoenix Assurance Company, Tube Investments Ltd, the State Building Society (1960–1964) and was the vice-chairman of the British Oxygen Company (1964–1966).

He took a personal interest in the preservation of the early 19th-century frigate HMS Unicorn in 1962.[29]

Reith was appointed Lord Rector of Glasgow University from 1965 to 1968.

In 1967, he accepted the much-cherished post of Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. His final television appearance was in a three-part documentary series entitled Lord Reith Looks Back in 1967, filmed at Glasgow University.

He died in Stockbridge Edinburgh, Midlothian after a fall, at the age of 81. In accordance with his wishes, his ashes were buried at the ancient, ruined chapel of Rothiemurchus in Aviemore, Inverness-shire.

Biographical works

Reith wrote two volumes of autobiography: Into The Wind in 1956 and Wearing Spurs in 1966. Two biographical volumes appeared shortly after his death: Only the Wind Will Listen by Andrew Boyle (1972), and a volume of his diaries edited by the Oxford academic Charles Stuart (1975). It was not until The Expense of Glory (1993) by Ian McIntyre that Reith's unexpurgated diaries and letters were published.

Attitude to fascism

In 1975, excerpts from Reith's diary were published which showed he had, during the 1930s, harboured pro-fascist views.[30] On 9 March 1933, he wrote: "I am pretty certain ... that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again. They are being ruthless and most determined." [30] Following the July 1934 Night of the Long Knives, in which the Nazis ruthlessly exterminated their internal dissidents, Reith wrote: "I really admire the way Hitler has cleaned up what looked like an incipient revolt. I really admire the drastic actions taken, which were obviously badly needed."[30] After Czechoslovakia was invaded by the Nazis in 1939 he wrote: "Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency."[30][31]

Reith also expressed admiration for Benito Mussolini.[30][32] Reith's daughter, Marista Leishman, wrote that in the 1930s her father did everything possible to keep Winston Churchill and other anti-appeasement Conservatives off the airwaves.[citation needed]

Honours and styles

Honours

- Knight Bachelor (Kt.) (1927 New Year Honours List)[33]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, Civil Division (GBE) (1934 Birthday Honours List)[34]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) (1939 New Year Honours List)[35]

- Member of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (PC) (January 1940)[36]

- Baron Reith, of Stonehaven in the County of Kincardine (21 October 1940)[37]

- Companion of the Order of the Bath, Military Division (CB) (1945 New Year Honours)[38]

- Efficiency Decoration (ED; though as a former Territorial Army officer, Lord Reith continued to use the post-nominal of TD) (22 July 1947)[39]

- Knight of the Order of the Thistle (KT) (18 February 1969)[40]

Styles

- 1889 – October 1917: John Charles Walsham Reith

- October 1917 – May 1918: Captain John Charles Walsham Reith[41]

- May 1918 – April 1919: Captain (Temp. Major) John Charles Walsham Reith[42]

- April 1919 – January 1927: Captain John Charles Walsham Reith[43][44]

- January 1927 – June 1934: Captain Sir John Charles Walsham Reith[33]

- June 1934 – January 1939: Captain Sir John Charles Walsham Reith, GBE[34]

- January 1939 – January 1940: Captain Sir John Charles Walsham Reith, GCVO, GBE[35]

- January–February 1940: Captain The Right Honourable Sir John Charles Walsham Reith, GCVO, GBE[36]

- February–October 1940: Captain The Right Honourable Sir John Charles Walsham Reith, GCVO, GBE, MP

- October–June 1942: Captain The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, GCVO, GBE, PC [37]

- June 1942 – January 1943: Captain (Temp. Lieutenant, RNVR) The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, GCVO, GBE, PC, RNVR[45]

- January 1943 – January 1945: Captain (Actg. Temp. Captain, RNVR) The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, GCVO, GBE, PC, RNVR

- January 1945 – July 1947: Captain (Actg. Temp. Captain, RNVR) The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, GCVO, GBE, CB, PC, RNVR[38]

- July 1947 – February 1969: Major The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, GCVO, GBE, CB, TD,[39] PC

- February 1969 – June 1971: Major The Right Honourable The Lord Reith, KT, GCVO, GBE, CB, TD, PC[40]

Personal life

Aged 22, Reith met 15-year-old male Charlie Bowser. Reith had what has been variously described as "a deep affection"[46] and "love" for Bowser. Opinions have varied on the nature of Reith's relationship; in the view of both his biographer, and his daughter,[47] it was homosexual. Reith all but severed it, burning the correspondence from Bowser, after he married his wife Muriel in 1921; they remained married until his death in 1971. However, Reith recorded Bowser's birthday in his diary for the rest of his life.[5] He and Muriel had two children, Christopher (1926–2017) and Marista (1932–2019).[48]

In popular culture

Reith was the protagonist of Jack Thorne's 2023 play When Winston Went to War with the Wireless, played by Stephen Campbell Moore; Charlie Bowser was played by Luke Newberry and Muriel Reith by Mariam Haque.[49]

He was commemorated in the Public Service Broadcasting album This New Noise, about the foundation of the BBC, with the song "An Unusual Man".[50]

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.