Loading AI tools

British businessman and architect (1761–1837) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lieutenant-Colonel James Burton (né James Haliburton; 29 July 1761 – 31 March 1837) was an English property developer. He was the most successful property developer of Regency and of Georgian London, in which he built over 3000 properties in 250 acres. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says that Burton was "the most successful developer in late Georgian London, responsible for some of its most characteristic architecture".

James Burton | |

|---|---|

Pyramidal Tomb of James Burton (1761–1837) and Burton family at St Leonards-on-Sea, England | |

| Born | 29 July 1761 |

| Died | 31 March 1837 St Leonards-on-Sea, England |

| Education | Homeschooled |

| Occupation(s) | Property developer; architect; Gunpowder Manufacturer |

| Notable work | |

| Children | 10 that survived infancy including: |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | |

Burton built most of Bloomsbury (including Bedford Square, Russell Square, Bloomsbury Square, Tavistock Square, and Cartwright Gardens), and St John's Wood, Regent Street, Regent Street St. James, Waterloo Place, St. James's, Swallow Street, Regent's Park (including its Inner Circle villas in addition to Chester Terrace, Cornwall Terrace, Clarence Terrace, and York Terrace). He also financed and built the projects of John Nash at Regent's Park (most of which were designed by his son Decimus Burton rather than by Nash) to the extent that the Commissioners of Woods described James, not Nash, as 'the architect of Regent's Park'. Burton also developed the town of St Leonards-on-Sea, which is now part of Hastings.

Burton was a member of London high society during the Georgian era and during the Regency era. He was an early member of the Athenaeum Club, London, whose Clubhouse his company built to a design by his son Decimus Burton, who was the club's "prime member". Burton was a friend of Princess Victoria (the future Queen Victoria), and of the Duchess of Kent. He was Master of the Worshipful Company of Tylers and Bricklayers, and in 1810/11 Sheriff of Kent. Burton's children included the Egyptologist James Burton; the physician Henry Burton; and the architect Decimus Burton. He was the grandfather of Constance Mary Fearon, who was the founder of the Francis Bacon Society.

The Burtons' London mansion, The Holme of Regent's Park (which was built by Burton's company and designed by Decimus Burton), was described by 20th century architecture critic Ian Nairn as 'a definition of Western civilization in a single view'. Burton also built the Burtons' Tonbridge mansion Mabledon.

James Burton was born in Strand, London, as James Haliburton, on 29 July 1761.[1][2] He was the son of William Haliburton (1731–1785),[1] who was a Scottish[2][3] property-developer whose family were from Roxburghshire,[1][4] and of Mary Foster (who was previously Mary Johnson; 1735–1785), whom his father married in 1760. Mary Foster was the daughter of Nicholas Foster of Kirkby Fleetham, Yorkshire.[5][2]

William Haliburton and Mary Foster had two sons, James and another who died in infancy.[2][1][5] Burton's paternal great-grandparents were Rev. James Haliburton (1681 – 1756) and Margaret Eliott (who was the daughter of Sir William Eliott, 2nd Baronet and the aunt of George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield).[5]

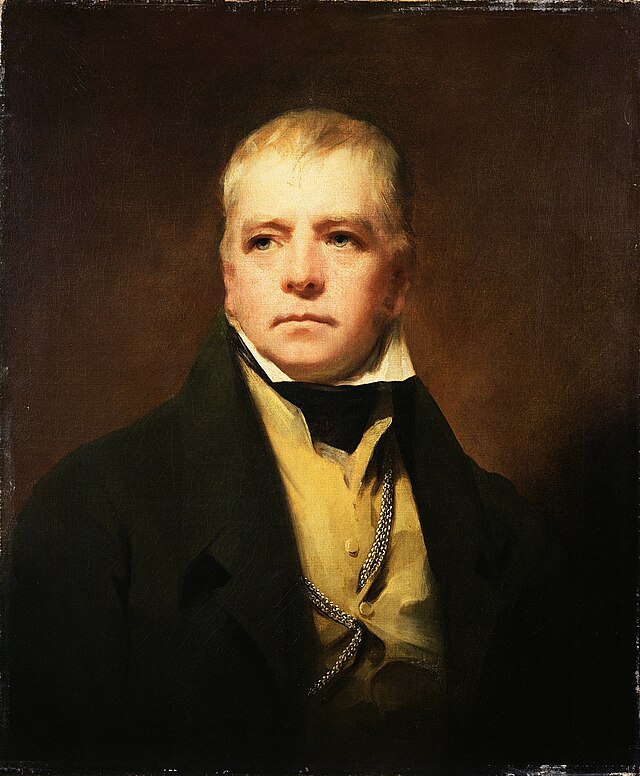

James Burton's father William was descended from John Haliburton (1573 – 1627)[5][6] from whom Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet was descended on the maternal side.[7][1][6] Burton was a cousin of the Canadian author and British Tory MP Thomas Chandler Haliburton,[8] and of Lord Haliburton,[3][9][10] who was the first Canadian to be raised to the Peerage of the United Kingdom.[11]

James (b. 1761) was christened with the name 'James Haliburton' at Presbyterian Chapel, Soho, London.[1][5] He shortened his surname to Burton in 1794,[7][3] and between the birth of his fourth child and the birth of his fifth child.[1][6][5]

James was educated at a day school in Covent Garden before he was privately tutored,[12] including in architecture. In July 1776 he was articled to a surveyor named James Dalton,[2] with whom he remained for six years,[12] until 1782, when he commenced with speculative construction projects,[1] in some of which Dalton was his partner.[2]

The architectural scholar Guy Williams contends, "He [Burton] was no ordinary builder. He could have put up an imposing and beautifully proportioned building, correct in every constructional detail, from the roughest of sketches tossed patronizingly at him by a "gentleman architect"".[1] James's industry quickly made him 'most gratifyingly rich'.[30] Burton worked as an 'Architect and Builder' in Southwark between 1785 and 1792.[31]

By 1787, Burton had established a positive reputation in Southwark: in 1786 he had built the Blackfriars Rotunda in Great Surrey Street (now Blackfriars Road) to house the Leverian Museum,[2] for land agent and museum proprietor James Parkinson;[32] this building subsequently housed the Southwark Institution.[2]

Burton when aged 28 years first proposed to build on the land that was made available by the Foundling Hospital,[2] on which he worked from 1789.[31] He built the earliest part of the Royal Veterinary College in Camden Town in 1792 - 1793.[2]

""He [Burton] was no ordinary builder. He could have put up an imposing and beautifully proportioned building, correct in every constructional detail, from the roughest of sketches tossed patronizingly at him by a "gentleman architect"".[1]

Architectural historian Guy Williams, about James Burton (b. 1761), in 1990.[1]

Between 1790 and 1792, he asked the Governors of the Foundling Hospital for a permission to exclusively build on the whole of Brunswick Square, but they underestimated his ability, and declined to waive their rule of not allowing any one speculator to develop more than a small proportion of the ground, and granted Burton only a small part of land on the south side and part of Guildford Street. Subsequently, however, Burton expanded this estate with further purchases until he became the most important builder on the hospital's estate,[2] and owned most of its western property: between 1792 and 1802 he built 586 houses on the estate, on which he spent over £400,000,[2] to bring the total number of his constructions on the estate to 600.[33] Samuel Pepys Cockerell, advisor to the Governors of the Foundling Hospital, commended Burton's excellence:

"Without such a man [James Burton], possessed of very considerable talents, unwearied industry, and a capital of his own, the extraordinary success of the improvement of the Foundling Estate could not have taken place... By his own peculiar resources of mind, he has succeeded in disposing of his buildings and rents, under all disadvantages of war, and of an unjust clamour which has repeatedly been raised against him. Mr. Burton was ready to come forward with money and personal assistance to relieve and help forward those builders who were unable to proceed in their contracts; and in some instances he has been obliged to resume the undertaking and complete himself what has been weakly and imperfectly proceeded with...".[34]

The contemporary Oxford Dictionary of National Biography contends that 'there is certainly no doubt about his energy and financial acumen'.[2] Burton was vigorously industrious, and quickly became 'most gratifyingly rich'.[30] Throughout his development of the Foundling Hospital Estate, Burton was encouraged by Francis Russell, 5th Duke of Bedford, and his successor, John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, and by the Skinners' Company to develop the remainder of Bloomsbury, including their adjacent estates.[2] In 1800, Burton bought a portion of the London estate of the Dukes of Bedford,[30] and immediately demolished the Bedfords decaying London mansion, Bedford House, on the site of which he constructed several family homes, including the houses of Bedford Place[30] and Russell Square.[2]

"James Burton became adept at relieving the monotony of long residential terraces by allowing their central blocks to project slightly from the surfaces to each side, and by bringing forward, too, the houses at each end. [...] The ironwork in a classical style in James Burton's Bloomsbury terraces was, and often still is, particularly fine, though mass produced".[30]

Architectural historian Guy Williams, about James Burton (b. 1761), in 1990.[30]

In these Bloomsbury developments, Burton again demonstrated his architectural flair, as Williams describes: "James Burton became adept at relieving the monotony of long residential terraces by allowing their central blocks to project slightly from the surfaces to each side, and by bringing forward, too, the houses at each end". Williams also records that "the ironwork in a classical style in James Burton's Bloomsbury terraces was, and often still is, particularly fine, though mass produced".[30] The Bloomsbury Conservation Areas Advisory Council describes Burton's Bloomsbury terraces, "His terraces are in his simple but eloquent Neoclassical style, with decorative doorcases, recessed sash windows in compliance with the latest fire regulations, and more stucco than before".[13] Jane Austen described Burton's new area of London in Emma: "Our part of London is so very superior to most others! - You must not confound us with London in general, my dear sir. The neighbourhood of Brunswick Square is very different from all the rest".[14]

In 1970, John Lehmann predicted that Burton's Bloomsbury would soon disappear "except for a few isolated rows... to remind us of man-sized architecture in a vanished age of taste".[13] Burton exhibited his design of the south side of Russell Square at the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1800. Burton's urban designs were characterized by spacious formal layouts of terraces, squares, and crescents.[2]

In 1807 Burton expanded his Bloomsbury development north, and was also involved extensively in the early development of St John's Wood.[18][19] He then left London for a project in Tunbridge Wells but returned in 1807 to build over the Skinners Company ground between the Bedford Estate and the lands owned by the Foundling Hospital, where he built Burton Street and Burton Crescent (now Cartwright Gardens), including, for himself, the Tavistock House, on ground now occupied by the British Medical Association, where he lived until he moved to The Holme in Regent's Park, which was designed for him by his son Decimus Burton.[33] Burton also developed the Lucas Estate.[35]

Burton constructed some houses at Tunbridge Wells between 1805 and 1807. Burton developed Waterloo Place, St. James's, between 1815 and 1816.[2] In 1815, James Burton took Decimus to Hastings, where the two would later design and build St Leonards-on-Sea, and, in 1816, Decimus commenced work in the James Burton's office.[36] Whilst working for his father, Decimus was present in the design and construction of Regent Street St. James (Lower Regent Street).[22][23] Simultaneously, George Maddox taught Decimus architectural draughtsmanship, including the details of the five orders. After his first year of tuition by his father and Maddox, Decimus submitted to the Royal Academy a design for a bridge, which was commended by the academy.[22]

Between 1785 and 1823, before many of his Regent's Park terraces were complete, James Burton had constructed at least 2366 houses in London.[2]

The parents of John Nash (b. 1752), and Nash himself during his childhood, lived in Southwark,[37] where Burton worked as an 'Architect and Builder' and developed a positive reputation for prescient speculative building between 1785 and 1792.[31] Burton built the Blackfriars Rotunda in Great Surrey Street (now Blackfriars Road) to house the Leverian Museum,[2] for land agent and museum proprietor James Parkinson.[32]

However, whereas Burton was vigorously industrious, and quickly became 'most gratifyingly rich',[30] Nash's early years in private practice, and his first speculative developments, which failed either to sell or let, were unsuccessful, and Nash's consequent financial shortage was exacerbated by the 'crazily extravagant' wife, whom he had married before he had completed his training, until he was declared bankrupt in 1783.[38] To resolve his financial shortage, Nash cultivated the acquaintance of Burton, and Burton consented to patronize him.[39]

James Burton was responsible for the social and financial patronage of the majority of Nash's London designs,[25] in addition to for their construction.[40] Architectural scholar Guy Williams has written, 'John Nash relied on James Burton for moral and financial support in his great enterprises. Decimus had showed precocious talent as a draughtsman and as an exponent of the classical style... John Nash needed the son's aid, as well as the father's'.[25] Subsequent to the Crown Estate's refusal to finance them, James Burton agreed to personally finance the construction projects of John Nash at Regent's Park, which he had already been commissioned to construct:[2][40] consequently, in 1816, Burton purchased many of the leases of the proposed terraces around, and proposed villas within, Regent's Park, and, in 1817, Burton purchased the leases of five of the largest blocks on Regent Street.[2] The first property to be constructed by Burton in the vicinity of Regent's Park was his own mansion: The Holme, which was designed by his son, Decimus Burton, and completed in 1818. Burton's extensive financial involvement 'effectively guaranteed the success of the project'.[2] In return, Nash agreed to promote the career of Decimus Burton.[40]

Such were James Burton's contributions to the project that the Commissioners of Woods described James, not Nash, as 'the architect of Regent's Park'.[41] Contrary to popular belief, the dominant architectural influence in many of the Regent's Park projects (including Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Chester Terrace, Clarence Terrace, and the villas of the Inner Circle, all of which were constructed by James Burton's company)[2] was Decimus Burton, not John Nash, who was appointed architectural 'overseer' for Decimus's projects.[41] To the chagrin of Nash, Decimus largely disregarded his advice and developed the Terraces according to his own style, to the extent that Nash sought the demolition and complete rebuilding of Chester Terrace, but in vain.[42][2] Decimus subsequently eclipsed Nash and emerged as the primary influence of the design of Carlton House Terrace,[40] where he exclusively designed No. 3 and No. 4.[43]

James Burton's imperative contribution to the development of the West End is acknowledged increasingly since the 20th century: including by Baines, John Summerson, Olsen, and Dana Arnold. Steen Eiler Rasmussen, in London: The Unique City, commended Burton's buildings, but did not identify their architect.[35] The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography contends that Burton were 'the most successful developer in late Georgian London, responsible for some of its most characteristic architecture',[2] and the Burtons' St. Leonards Society that he were "probably the most significant builder of Georgian London".[7]

James Burton, from 1811,[2] invested in the manufacture of gunpowder at Powder Mills, Leigh that was managed by Burton and his eldest son, William Ford, who directed sales of the product from his office in the City of London.[44][45][2] The mills, which were initially known as the Ramhurst Powder Mills,[46] and later as the Tunbridge Gunpowder Works, were that established in 1811 in partnership with Sir Humphry Davy, who later sold his shares to the Burtons, who thereby became the sole owners of the Works.[2][47][48][49][44]

After the retirement of James Burton in 1824, William Ford became the sole owner of the mills until his death in 1856,[46][47] at which point the gunpowder business to his brother, Alfred Burton Mayor, of Hastings.

In 1827, James Burton realised that the ancient Manor of Gensing, which was situated between Hastings and the Bulverhythe Marshes, could be developed.[50] Decimus Burton advised against this prospective project of his father, which limited his supply of capital for his own development of the Calverley Estate,[50] but James ignored him, bought it, and proceeded to build St Leonards-on-Sea as a pleasure resort for the gentry.[2] James Burton designed the town 'on the twin principles of classical formality and picturesque irregularity', to rival Brighton.[2] The majority of the first part of the town had been completed by 1830.[2] In 1833, St. Leonards-on-Sea was described as 'a conceited Italian town'.[2]

During 1800, in which his tenth child Decimus was born, James Burton Senior resided at the 'very comfortable and well staffed' North House in the newly built Southampton Terrace at Bloomsbury.[30] He subsequently resided at Tavistock House, which later became the residence of Charles Dickens. Subsequent to the birth of his twelfth child, Jessy, in 1804, Burton purchased a site on a hill about one mile to the south of Tonbridge in Kent, where he constructed, to the designs of the architect Joseph T. Parkinson, in 1805,[31] a large mansion which he named Mabledon House,[51][2] which was described in 1810 by the local authority as 'an elegant imitation of an ancient castellated mansion'.[51] The majority of the stone that Burton needed for Mabledon was quarried from the hill on which Mabledon was to be built, but Burton also purchased stone from the demolition of the nearby mansion Penhurst Place.[51] Burton at Mabledon employed a bailiff and a gamekeeper, and hosted balls, and was invested as Sheriff of Kent[51] for 1810.[2] A diary written by James Burton, which records his activities between 1783 and 1811, is at Hastings Museum and Art Gallery.[52] The Burtons lived at Mabledon from 1805 to 1817.[53]

From 1818, Burton resided at The Holme, Regent's Park, which has been described as 'one of the most desirable private homes in London',[28] which was designed by James's son Decimus, and built by his own company.[2] The Holme was the second villa in Regent's Park, and the first to be either designed or constructed by the Burton family.[54] The hallmark of the Burton design is the large semi-circular bay that divided the principal elevation and that had two storeys.[54] The original villa also had a conservatory of polygonal form, which used wrought iron glazing bars, which then had been only recently patented, instead of the customary wooden bars.[54] The first villa to be constructed in the park was St. John's Lodge by John Raffield.[54]

The Burton family had residences and offices at 10, 12, and 14 Spring Gardens, St. James's Park, at the east end of The Mall, that were constructed by Decimus.[55][40] The Burton family also had offices at Old Broad Street in the City of London,[44] and at Lincoln's Inn Fields (at which Septimus Burton was a solicitor at Lincoln's Inn[56][9] and trained William Warwick Burton.[57][58]

Burton was Master of the Worshipful Company of Tylers and Bricklayers in 1801 to 1802.[2] In 1804, in response to the cessation of amicable relations with the French Republic, Burton recruited 1600 volunteers, whom he named the Loyal British Artificers,[30] at his expense, from the artificers that were in his employ,[30][2] and of which he became Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant,[30][12] for the eventuality of invasion by the French. The rally-point of Burton's Loyal British Artificers was to be the Tottenham Court Road.[30] Burton attended the funeral of Horatio Nelson in 1806.[12]

James Burton was an early member of the Athenaeum Club, London, as was his son, Decimus Burton,[59] who has been described as the 'prime member of the Athenaeum' by architectural scholar Guy Williams[60] who there 'mixed with many of the greatest in the land, meeting the most creative as well as those with enormous hereditary wealth'.[61] During 1820, Burton, his wife, and his children dined and attended the opera with George Bellas Greenough[62] to finalise Greenhough and Decimus's designs.[62] James and Decimus Burton were 'on excellent terms' with Princess Victoria,[61] and with the Duchess of Kent.[61] The Princess and the Duchess, with several courtiers, laid the foundation stone of a Decimus Burton School in Tunbridge Wells,[61] and, five weeks later, in autumn 1834, they stayed, by Decimus's invitation, at James Burton's villa at St Leonards-on-Sea, for several months, until several weeks into 1835.[63]

Elizabeth Burton died at St Leonards-on-Sea on 14 January 1837.[64] James Burton died at St Leonards-On-Sea on 31 March 1837.[64] James is buried in a pyramidal tomb in the churchyard of St Leonards-on-Sea, the town that he had designed and created, where a commemorative monument was erected.[2]

On 1 March 1783, at St. Clement Danes, Strand, London,[1] James Burton married Elizabeth Westley (12 December 1761 – 14 January 1837),[64][2] of Loughton, Essex,[1] daughter of John and Mary Westley.[5] They had six sons and six daughters,[6][5] ten of whom were alive at the time of their father's death on 31 March 1837.[2] Their first four children were all baptized at the church at which they had married, and entered in the registers with the surname 'Haliburton':[1] however, James and Elizabeth changed their surname to 'Burton' between the birth of their fourth child and the birth of their fifth child.[1][5][7][3]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.