Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Invention of the telephone

Technical and legal issues surrounding the development of the modern telephone From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The invention of the telephone was the culmination of work done by more than one individual, and led to an array of lawsuits relating to the patent claims of several individuals and numerous companies. Notable people included in this were Antonio Meucci, Philipp Reis, Elisha Gray and Alexander Graham Bell.

Replica of the telettrofono at Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci of Milan, Italy, invented by Antonio Meucci and credited by several sources as the first telephone.[1]

Remove ads

Early development

Summarize

Perspective

The concept of the telephone dates back to the string telephone or lover's telephone that has been known for centuries, comprising two diaphragms connected by a taut string or wire. Sound waves are carried as mechanical vibrations along the string or wire from one diaphragm to the other. The classic example is the tin can telephone, a children's toy made by connecting the two ends of a string to the bottoms of two metal cans, paper cups or similar items. The essential idea of this toy was that a diaphragm can collect voice sounds for reproduction at a distance. One precursor to the development of the electromagnetic telephone originated in 1833 when Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber invented an electromagnetic device for the transmission of telegraphic signals at the University of Göttingen, in Lower Saxony, helping to create the fundamental basis for the technology that was later used in similar telecommunication devices. Gauss's and Weber's invention is purported to be the world's first electromagnetic telegraph.[2]

Charles Grafton Page

In 1836-8, American Charles Grafton Page passed an electric current through a coil of wire placed between the poles of a horseshoe magnet. He observed that connecting and disconnecting the current caused a ringing sound in the magnet. He called this effect "galvanic music".[3] A similar phenomenon was reported by British inventor Edward Davy in 1837-8 and it was also pointed out by William Chappell that Michael Faraday had likely heard similar sounds during his own experiments with make and break circuits in the early 1830s.[4][5]

Innocenzo Manzetti

Innocenzo Manzetti considered the idea of a telephone as early as 1844, and may have made one in 1864, as an enhancement to an automaton built by him in 1849.

Charles Bourseul was a French telegraph engineer who proposed (but did not build) the first design of a "make-and-break" telephone in 1854. That is about the same time that Meucci later claimed to have created his first attempt at the telephone in Italy.

Bourseul explained: "Suppose that a man speaks near a movable disc sufficiently flexible to lose none of the vibrations of the voice; that this disc alternately makes and breaks the currents from a battery: you may have at a distance another disc which will simultaneously execute the same vibrations.... It is certain that, in a more or less distant future, a speech will be transmitted by electricity. I have made experiments in this direction; they are delicate and demand time and patience, but the approximations obtained promise a favorable result".

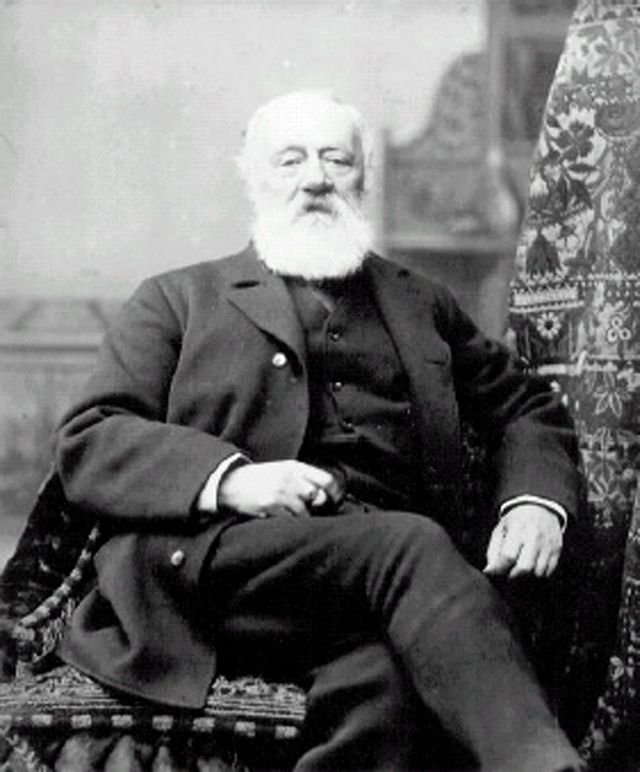

Antonio Meucci

An early communicating device was invented around 1854 by Antonio Meucci, who called it a telettrofono (lit. "telectrophone"). In 1871 Meucci filed a patent caveat at the US Patent Office. His caveat describes his invention, but does not mention a diaphragm, electromagnet, conversion of sound into electrical waves, conversion of electrical waves into sound, or other essential features of an electromagnetic telephone.

The first American demonstration of Meucci's invention took place in Staten Island, New York in 1854.[8] In 1861, a description of it was reportedly published in an Italian-language New York newspaper, although no known copy of that newspaper issue or article has survived to the present day. Meucci claimed to have invented a paired electromagnetic transmitter and receiver, where the motion of a diaphragm modulated a signal in a coil by moving an electromagnet, although this was not mentioned in his 1871 U.S. patent caveat. A further discrepancy observed was that the device described in the 1871 caveat employed only a single conduction wire, with the telephone's transmitter-receivers being insulated from a 'ground return' path.

Meucci studied the principles of electromagnetic voice transmission for many years and was able to realise his dream of transmitting his voice through wires in 1856. He installed a telephone-like device within his house in order to communicate with his wife who was ill at the time. Some of Meucci's notes purportedly written in 1857 describe the basic principle of electromagnetic voice transmission — or in other words, the telephone.[9]

In the 1880s Meucci was credited with the early invention of inductive loading of telephone wires to increase long-distance signals. Serious burns from an accident, a lack of English, and poor business abilities resulted in Meucci's failing to develop his inventions commercially in America. Meucci demonstrated some sort of instrument in 1849 in Havana, Cuba, however, this may have been a variant of a string telephone that used wire. Meucci has been further credited with the invention of an anti-sidetone circuit. However, examination showed that his solution to sidetone was to maintain two separate telephone circuits and thus use twice as many transmission wires. The anti-sidetone circuit later introduced by Bell Telephone instead canceled sidetone through a feedback process.

An American District Telegraph (ADT) laboratory reportedly lost some of Meucci's working models, his wife reportedly disposed of others and Meucci, who sometimes lived on public assistance, chose not to renew his 1871 teletrofono patent caveat after 1874.

A resolution was passed by the United States House of Representatives in 2002 that said Meucci did pioneering work on the development of the telephone.[10][11][12][13] The resolution said that "if Meucci had been able to pay the $10 fee to maintain the caveat after 1874, no patent could have been issued to Bell".

The Meucci resolution by the US Congress was promptly followed by a Canada legislative motion by Canada's 37th Parliament, declaring Alexander Graham Bell as the inventor of the telephone. Others in Canada disagreed with the Congressional resolution, some of whom provided criticisms of both its accuracy and intent.

Chronology of Meucci's invention

A retired director general of the Telecom Italia central telecommunications research institute (CSELT), Basilio Catania,[14] and the Italian Society of Electrotechnics, "Federazione Italiana di Elettrotecnica", have devoted a Museum to Antonio Meucci, constructing a chronology of his invention of the telephone and tracing the history of the two legal trials involving Meucci and Alexander Graham Bell.[15][16][17]

They claim that Meucci was the actual inventor of the telephone, and base their argument on reconstructed evidence. What follows, if not otherwise stated, is a summary of their historic reconstruction.[18]

- In 1834 Meucci constructed a kind of acoustic telephone as a way to communicate between the stage and control room at the theatre "Teatro della Pergola" in Florence. This telephone is constructed on the model of pipe-telephones on ships and is still working.[19]

- In 1848 Meucci developed a popular method of using electric shocks to treat rheumatism. He used to give his patients two conductors linked to 60 Bunsen batteries and ending with a cork. He also kept two conductors linked to the same Bunsen batteries. He used to sit in his laboratory, while the Bunsen batteries were placed in a second room and his patients in a third room. In 1849 while providing a treatment to a patient with a 114 V electrical discharge, in his laboratory Meucci heard his patient's scream through the piece of copper wire that was between them, from the conductors he was keeping near his ear. His intuition was that the "tongue" of copper wire was vibrating just like a leaf of an electroscope; which means that there was an electrostatic effect. In order to continue the experiment without hurting his patient, Meucci covered the copper wire with a piece of paper. Through this device he heard inarticulated human voice. He called this device "telegrafo parlante" (litt. "talking telegraph").[20]

- On the basis of this prototype, Meucci worked on more than 30 kinds of sound transmitting devices inspired by the telegraph model as did other pioneers of the telephone, such as Charles Bourseul, Philipp Reis, Innocenzo Manzetti and others. Meucci later claimed that he did not think about transmitting voice by using the principle of the telegraph "make-and-break" method, but he looked for a "continuous" solution that did not interrupt the electric current.

- Meucci later claimed that he constructed the first electromagnetic telephone, made of an electromagnet with a nucleus in the shape of a horseshoe bat, a diaphragm of animal skin, stiffened with potassium dichromate and keeping a metal disk stuck in the middle. The instrument was hosted in a cylindrical carton box.[21] He said he constructed this as a way to connect his second-floor bedroom to his basement laboratory, and thus communicate with his wife who was an invalid.

- Meucci separated the two directions of transmission in order to eliminate the so-called "local effect", adopting what we would call today a 4-wire-circuit. He constructed a simple calling system with a telegraphic manipulator which short-circuited the instrument of the calling person, producing in the instrument of the called person a succession of impulses (clicks), much more intense than those of normal conversation. As he was aware that his device required a bigger band than a telegraph, he found some means to avoid the so-called "skin effect" through superficial treatment of the conductor or by acting on the material (copper instead of iron). He successfully used an insulated copper plait, thus anticipating the litz wire used by Nikola Tesla in RF coils.

- In 1864 Meucci later claimed that he realized his "best device", using an iron diaphragm with optimized thickness and tightly clamped along its rim. The instrument was housed in a shaving-soap box, whose cover clamped the diaphragm.

- In August 1870, Meucci later claimed that he obtained transmission of articulate human voice at a mile distance by using as a conductor a copper plait insulated by cotton. He called his device "teletrofono". Drawings and notes by Antonio Meucci dated September 27, 1870, show coils of wire on long-distance telephone lines.[22] The painting made by Nestore Corradi in 1858 mentions the sentence "Electric current from the inductor pipe".

The above information was published in the Scientific American Supplement No. 520 of December 19, 1885,[23] based on reconstructions produced in 1885, for which there was no contemporary pre-1875 evidence. Meucci's 1871 caveat did not mention any of the telephone features later credited to him by his lawyer, and which were published in that Scientific American Supplement, a major reason for the loss of the 'Bell v. Globe and Meucci' patent infringement court case, which was decided against Globe and Meucci.[24]

Johann Philipp Reis

The Reis telephone was developed from 1857 onwards. Allegedly, the transmitter was difficult to operate, since the relative position of the needle and the contact were critical to the device's operation. Thus, it can be called a "telephone", since it did transmit voice sounds electrically over distance, but was hardly a commercially practical telephone in the modern sense.

In 1874, the Reis device was tested by the British company Standard Telephones and Cables (STC). The results also confirmed it could transmit and receive speech with good quality (fidelity), but relatively low intensity.[citation needed]

Reis' new invention was articulated in a lecture before the Physical Society of Frankfurt on 26 October 1861, and a description, written by himself for Jahresbericht a month or two later. It created a good deal of scientific excitement in Germany; models of it were sent abroad, to London, Dublin, Tiflis, and other places. It became a subject for popular lectures, and an article for scientific cabinets.

Thomas Edison tested the Reis equipment and found that "single words, uttered as in reading, speaking and the like, were perceptible indistinctly, notwithstanding here also the inflections of the voice, the modulations of interrogation, wonder, command, etc., attained distinct expression."[25] He used Reis's work for the successful development of the carbon microphone. Edison acknowledged his debt to Reis thus:

The first inventor of a telephone was Phillip Reis of Germany only musical not articulating. The first person to publicly exhibit a telephone for transmission of articulate speech was A. G. Bell. The first practical commercial telephone for transmission of articulate speech was invented by myself. Telephones used throughout the world are mine and Bell's. Mine is used for transmitting. Bell's is used for receiving.[26]

Cyrille Duquet

Cyrille Duquet invents the handset.[27]

Duquet obtained a patent on 1 Feb. 1878 for a number of modifications "giving more facility for the transmission of sound and adding to its acoustic properties," and in particular for the design of a new apparatus combining the speaker and receiver in a single unit.[27]

Remove ads

Electro-magnetic transmitters and receivers

Summarize

Perspective

Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray, of Highland Park, Illinois, also devised a tone telegraph of this kind about the same time as La Cour. In Gray's tone telegraph, several vibrating steel reeds tuned to different frequencies interrupted the current, which at the other end of the line passed through electromagnets and vibrated matching tuned steel reeds near the electromagnet poles. Gray's "harmonic telegraph", with vibrating reeds, was used by the Western Union Telegraph Company. Since more than one set of vibration frequencies – that is to say, more than one musical tone – can be sent over the same wire simultaneously, the harmonic telegraph can be utilized as a 'multiplex' or many-ply telegraph, conveying several messages through the same wire at the same time. Each message can either be read by an operator by the sound, or from different tones read by different operators, or a permanent record can be made by the marks drawn on a ribbon of traveling paper by a Morse recorder. On July 27, 1875, Gray was granted U.S. patent 166,096 for "Electric Telegraph for Transmitting Musical Tones" (the harmonic).

On February 14, 1876, at the US Patent Office, Gray's lawyer filed a patent caveat for a telephone on the very same day that Bell's lawyer filed Bell's patent application for a telephone. The water transmitter described in Gray's caveat was strikingly similar to the experimental telephone transmitter tested by Bell on March 10, 1876, a fact which raised questions about whether Bell (who knew of Gray) was inspired by Gray's design or vice versa. Although Bell did not use Gray's water transmitter in later telephones, evidence suggests that Bell's lawyers may have obtained an unfair advantage over Gray.[28]

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell had pioneered a system called visible speech, developed by his father, to teach deaf children. In 1872 Bell founded a school in Boston, Massachusetts, to train teachers of the deaf. The school subsequently became part of Boston University, where Bell was appointed professor of vocal physiology in 1873.

As Professor of Vocal Physiology at Boston University, Bell was engaged in training teachers in the art of instructing the deaf how to speak and experimented with the Leon Scott phonautograph in recording the vibrations of speech. This apparatus consists essentially of a thin membrane vibrated by the voice and carrying a light-weight stylus, which traces an undulatory line on a plate of smoked glass. The line is a graphic representation of the vibrations of the membrane and the waves of sound in the air.[29]

This background prepared Bell for work with spoken sound waves and electricity. He began his experiments in 1873–1874 with a harmonic telegraph, following the examples of Bourseul, Reis, and Gray. Bell's designs employed various on-off-on-off make-break current-interrupters driven by vibrating steel reeds which sent interrupted current to a distant receiver electro-magnet that caused a second steel reed or tuning fork to vibrate.[30]

During a June 2, 1875, experiment by Bell and his assistant Thomas Watson, a receiver reed failed to respond to the intermittent current supplied by an electric battery. Bell told Watson, who was at the other end of the line, to pluck the reed, thinking it had stuck to the pole of the magnet. Watson complied, and to his astonishment Bell heard a reed at his end of the line vibrate and emit the same timbre of a plucked reed, although there were no interrupted on-off-on-off currents from a transmitter to make it vibrate.[31] A few more experiments soon showed that his receiver reed had been set in vibration by the magneto-electric currents induced in the line by the motion of the distant receiver reed in the neighborhood of its magnet. The battery current was not causing the vibration but was needed only to supply the magnetic field in which the reeds vibrated. Moreover, when Bell heard the rich overtones of the plucked reed, it occurred to him that since the circuit was never broken, all the complex vibrations of speech might be converted into undulating (modulated) currents, which in turn would reproduce the complex timbre, amplitude, and frequencies of speech at a distance.

After Bell and Watson discovered on June 2, 1875, that movements of the reed alone in a magnetic field could reproduce the frequencies and timbre of spoken sound waves, Bell reasoned by analogy with the mechanical phonautograph that a skin diaphragm would reproduce sounds like the human ear when connected to a steel or iron reed or hinged armature. On July 1, 1875, he instructed Watson to build a receiver consisting of a stretched diaphragm or drum of goldbeater's skin with an armature of magnetized iron attached to its middle, and free to vibrate in front of the pole of an electromagnet in circuit with the line. A second membrane-device was built for use as a transmitter.[32] This was the "gallows" phone. A few days later they were tried together, one at each end of the line, which ran from a room in the inventor's house, located at 5 Exeter Place in Boston, to the cellar underneath.[33] Bell, in the work room, held one instrument in his hands, while Watson in the cellar listened at the other. Bell spoke into his instrument, "Do you understand what I say?" and Watson answered "Yes". However, the voice sounds were not distinct and the armature tended to stick to the electromagnet pole and tear the membrane.

On 10 March 1876, in a test, between two rooms in a single building, above Palace Theatre, at 109 Court Street,[34] not far from Scollay Square in Boston[35][36] showed that the telephone worked, but so far, only at a short range.[37][38]

In 1876, Bell became the first to obtain a patent for an "apparatus for transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically", after experimenting with many primitive sound transmitters and receivers. Because of illness and other commitments, Bell made little or no telephone improvements or experiments for eight months until after his U.S. patent 174,465 was published.,[32] but within a year the first telephone exchange was built in Connecticut and the Bell Telephone Company was created in 1877, with Bell the owner of a third of the shares, quickly making him a wealthy man. Organ builder Ernest Skinner reported in his autobiography that Bell offered Boston-area organ builder Hutchings a 50% interest in the company but Hutchings declined.[39]

In 1880, Bell was awarded the French Volta Prize for his invention and with the money, founded the Volta Laboratory in Washington,[which?] where he continued experiments in communication, in medical research, and in techniques for teaching speech to the deaf, working with Helen Keller among others. In 1885 he acquired land in Nova Scotia and established a summer home there where he continued experiments, particularly in the field of aviation.

Bell himself said that the telephone was invented in Canada but made in the United States.[40]

Bell's success

The first successful bi-directional transmission of clear speech by Bell and Watson was made on March 10, 1876, when Bell spoke into the device, "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you." and Watson complied with the request. Bell tested Gray's liquid transmitter design[42] in this experiment, but only after Bell's patent was granted and only as a proof of concept scientific experiment[43] to prove to his own satisfaction that intelligible "articulate speech" (Bell's words) could be electrically transmitted.[44] Because a liquid transmitter was not practical for commercial products, Bell focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone after March 1876 and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public demonstrations or commercial use.[45]

Bell's telephone transmitter (microphone) consisted of a double electromagnet, in front of which a membrane, stretched on a ring, carried an oblong piece of soft iron cemented to its middle. A funnel-shaped mouthpiece directed the voice sounds upon the membrane, and as it vibrated, the soft iron "armature" induced corresponding currents in the coils of the electromagnet. These currents, after traversing the wire, passed through the receiver which consisted of an electromagnet in a tubular metal can having one end partially closed by a thin circular disc of soft iron. When the undulatory current passed through the coil of this electromagnet, the disc vibrated, thereby creating sound waves in the air.

This primitive telephone was rapidly improved. The double electromagnet was replaced by a single permanently magnetized bar magnet having a small coil or bobbin of fine wire surrounding one pole, in front of which a thin disc of iron was fixed in a circular mouthpiece. The disc served as a combined diaphragm and armature. On speaking into the mouthpiece, the iron diaphragm vibrated with the voice in the magnetic field of the bar-magnet pole, and thereby caused undulatory currents in the coil. These currents, after traveling through the wire to the distant receiver, were received in an identical apparatus. This design was patented by Bell on January 30, 1877. The sounds were weak and could only be heard when the ear was close to the earphone/mouthpiece, but they were distinct.

In the third of his tests in Southern Ontario, on August 10, 1876, Bell made a call via the telegraph line from the family homestead in Brantford, Ontario, to his assistant located in Paris, Ontario, some 13 kilometers away. This test was claimed by many sources as the world's first long-distance call.[46][47] The final test certainly proved that the telephone could work over long distances.

Public demonstrations

Early public demonstrations of Bell's telephone

Bell exhibited a working telephone at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in June 1876, where it attracted the attention of Brazilian emperor Pedro II plus the physicist and engineer Sir William Thomson (who would later be ennobled as the 1st Baron Kelvin). In August 1876 at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Thomson revealed the telephone to the European public. In describing his visit to the Philadelphia Exhibition, Thomson said, "I heard [through the telephone] passages taken at random from the New York newspapers: 'S.S. Cox Has Arrived' (I failed to make out the S.S. Cox); 'The City of New York', 'Senator Morton', 'The Senate Has Resolved To Print A Thousand Extra Copies', 'The Americans In London Have Resolved To Celebrate The Coming Fourth Of July!' All this my own ears heard spoken to me with unmistakable distinctness by the then circular disc armature of just such another little electro-magnet as this I hold in my hand."

Three great tests of the telephone

Only a few months after receiving U.S. Patent No. 174465 at the beginning of March 1876, Bell conducted three important tests of his new invention and the telephone technology after returning to his parents' home at Melville House (now the Bell Homestead National Historic Site) for the summer.

On March 10, 1876, Bell had used "the instrument" in Boston to call Thomas Watson who was in another room but out of earshot. He said, "Mr. Watson, come here – I want to see you" and Watson soon appeared at his side.[48]

In the first test call at a longer distance in Southern Ontario, on August 3, 1876, Alexander Graham's uncle, Professor David Charles Bell, spoke to him from the Brantford telegraph office, reciting lines from Shakespeare's Hamlet ("To be or not to be....").[49][50] The young inventor, positioned at the A. Wallis Ellis store in the neighboring community of Mount Pleasant,[49][51] received and may possibly have transferred his uncle's voice onto a phonautogram, a drawing made on a pen-like recording device that could produce the shapes of sound waves as waveforms onto smoked glass or other media by tracing their vibrations.

The next day on August 4 another call was made between Brantford's telegraph office and Melville House, where a large dinner party exchanged "....speech, recitations, songs and instrumental music".[49] To bring telephone signals to Melville House, Alexander Graham audaciously "bought up" and "cleaned up" the complete supply of stovepipe wire in Brantford.[52][53] With the help of two of his parents' neighbours,[54] he tacked the stovepipe wire some 400 metres (a quarter mile) along the top of fence posts from his parents' home to a junction point on the telegraph line to the neighbouring community of Mount Pleasant, which joined it to the Dominion Telegraph office in Brantford, Ontario.[55][56]

The third and most important test was the world's first true long-distance telephone call, placed between Brantford and Paris, Ontario on August 10, 1876.[57][58] For that long-distance call Alexander Graham Bell set up a telephone using telegraph lines at Robert White's Boot and Shoe Store at 90 Grand River Street North in Paris via its Dominion Telegraph Co. office on Colborne Street. The normal telegraph line between Paris and Brantford was not quite 13 km (8 miles) long, but the connection was extended a further 93 km (58 miles) to Toronto to allow the use of a battery in its telegraph office.[49][59] Granted, this was a one-way long-distance call. The first two-way (reciprocal) conversation over a line occurred between Cambridge and Boston (roughly 2.5 miles) on October 9, 1876.[60] During that conversation, Bell was on Kilby Street in Boston and Watson was at the offices of the Walworth Manufacturing Company.[61]

Scientific American described the three test calls in their September 9, 1876, article, "The Human Voice Transmitted by Telegraph".[59] Historian Thomas Costain referred to the calls as "the three great tests of the telephone".[62] One Bell Homestead reviewer wrote of them, "No one involved in these early calls could possibly have understood the future impact of these communication firsts".[63]

Later public demonstrations

A later telephone design was publicly exhibited on May 4, 1877, at a lecture given by Professor Bell in the Boston Music Hall. According to a report quoted by John Munro in Heroes of the Telegraph:

Going to the small telephone box with its slender wire attachments, Mr. Bell coolly asked, as though addressing someone in an adjoining room, "Mr. Watson, are you ready!" Mr. Watson, five miles away in Somerville, promptly answered in the affirmative, and soon was heard a voice singing "America". [...] Going to another instrument, connected by wire with Providence, forty-three miles distant, Mr. Bell listened a moment, and said, "Signor Brignolli, who is assisting at a concert in Providence Music Hall, will now sing for us." In a moment the cadence of the tenor's voice rose and fell, the sound being faint, sometimes lost, and then again audible. Later, a cornet solo played in Somerville was very distinctly heard. Still later, a three-part song came over the wire from Somerville, and Mr. Bell told his audience "I will switch off the song from one part of the room to another so that all can hear." At a subsequent lecture in Salem, Massachusetts, communication was established with Boston, eighteen miles distant, and Mr. Watson at the latter place sang "Auld Lang Syne", the National Anthem, and "Hail Columbia", while the audience at Salem joined in the chorus.[64]

On January 14, 1878, at Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight, Bell demonstrated the device to Queen Victoria,[65] placing calls to Cowes, Southampton and London. These were the first publicly witnessed long-distance telephone calls in the UK. The queen considered the process to be "quite extraordinary" although the sound was "quite faint".[66] She later asked to buy the equipment that was used, but Bell offered to make a model specifically for her.[67][68]

Summary of Bell's achievements

Bell did for the telephone what Henry Ford did for the automobile. Although not the first to experiment with telephonic devices, Bell and the companies founded in his name were the first to develop commercially practical telephones around which a successful business could be built and grow. Bell adopted carbon transmitters similar to Edison's transmitters and adapted telephone exchanges and switching plug boards developed for telegraphy. Watson and other Bell engineers invented numerous other improvements to telephony. Bell succeeded where others failed to assemble a commercially viable telephone system. It can be argued that Bell invented the telephone industry. Bell's first intelligible voice transmission over an electric wire was named an IEEE Milestone.[69]

Remove ads

Variable resistance transmitters

Summarize

Perspective

Water microphone – Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray recognized the lack of fidelity of the make-break transmitter of Reis and Bourseul and reasoned by analogy with the lover's telegraph, that if the current could be made to more closely model the movements of the diaphragm, rather than simply opening and closing the circuit, greater fidelity might be achieved. Gray filed a patent caveat with the US patent office on February 14, 1876, for a liquid microphone. The device used a metal needle or rod that was placed – just barely – into a liquid conductor, such as a water/acid mixture. In response to the diaphragm's vibrations, the needle dipped more or less into the liquid, varying the electrical resistance and thus the current passing through the device and on to the receiver. Gray did not convert his caveat into a patent application until after the caveat had expired and hence left the field open to Bell.

When Gray applied for a patent for the variable resistance telephone transmitter, the Patent Office determined "while Gray was undoubtedly the first to conceive of and disclose the (variable resistance) invention, as in his caveat of 14 February 1876, his failure to take any action amounting to completion until others had demonstrated the utility of the invention deprives him of the right to have it considered."[70]

Carbon microphone – Thomas Edison, Edward Hughes, Emile Berliner

The carbon microphone was independently developed around 1878 by David Edward Hughes in England and Emile Berliner and Thomas Edison in the US. Although Edison was awarded the first patent in mid-1877, Hughes had demonstrated his working device in front of many witnesses some years earlier, and most historians credit him with its invention.

Thomas Alva Edison took the next step in improving the telephone with his invention in 1878 of the carbon grain "transmitter" (microphone) that provided a strong voice signal on the transmitting circuit that made long-distance calls practical. Edison discovered that carbon grains, squeezed between two metal plates, had a variable electrical resistance that was related to the pressure. Thus, the grains could vary their resistance as the plates moved in response to sound waves, and reproduce sound with good fidelity, without the weak signals associated with electromagnetic transmitters.

The carbon microphone was further improved by Emile Berliner, Francis Blake, David E. Hughes, Henry Hunnings, and Anthony White. The carbon microphone remained standard in telephony until the 1980s, and is still being produced.

Remove ads

From primitive intercoms to real telephony

Summarize

Perspective

Additional inventions such as the call bell, central telephone exchange, common battery, ring tone, amplification, trunk lines, and wireless phones – at first cordless and then fully mobile – made the telephone the useful and widespread apparatus as it is now.

Telephone exchanges

During the time of the electrical telegraph, its main users included post offices, railway stations, major government centers (ministries), stock exchanges, a limited number of nationally distributed newspapers, large internationally significant corporations, and some very affluent individuals.[71] Although telephone devices were available before the invention of the telephone exchange, their success and efficient operation would not have been feasible using the same system as the contemporary telegraph. Before the development of the telephone exchange switchboard, early telephones operated as intercoms, as the telephone device was hardwired to connect with only one other telephone device, such as linking a person's home to their workplace.[72]

The telephone exchange was an idea of the Hungarian engineer Tivadar Puskás (1844–1893) in 1876, while he was working for Thomas Edison on a telegraph exchange.[73][74][75][76] Puskás was working on his idea for an electrical telegraph exchange when Alexander Graham Bell received the first patent for the telephone. This caused Puskás to take a fresh look at his own work and he refocused on perfecting a design for a telephone exchange. He then got in touch with the U.S. inventor Thomas Edison who liked the design. According to Edison, "Tivadar Puskas was the first person to suggest the idea of a telephone exchange".[77]

Remove ads

Controversies

Summarize

Perspective

Bell has been widely recognized as the "inventor" of the telephone outside of Italy, where Meucci was championed as its inventor, and outside of Germany, where Reis was recognized as the "inventor". In the United States, there are numerous reflections of Bell as a North American icon for inventing the telephone, and the matter was for a long time non-controversial. In June 2002, however, the United States House of Representatives passed a symbolic bill recognizing the contributions of Antonio Meucci "in the invention of the telephone" (not "for the invention of the telephone"), throwing the matter into some controversy. Ten days later the Canadian parliament countered with a symbolic motion attributing the invention of the telephone to Bell.

Champions of Meucci, Manzetti, and Gray have each offered fairly precise tales of a contrivance whereby Bell actively stole the invention of the telephone from their specific inventor. In the 2002 congressional resolution, it was inaccurately noted that Bell worked in a laboratory in which Meucci's materials had been stored, and claimed that Bell must thus have had access to those materials. Manzetti claimed that Bell visited him and examined his device in 1865. In 1886 it was publicly alleged by Zenas Wilber, a patent examiner, that Bell paid him one hundred dollars, when he allowed Bell to look at Gray's confidential patent filing.[78]

One of the valuable claims in Bell's 1876 U.S. patent 174,465 was claim 4, a method of producing variable electric current in a circuit by varying the resistance in the circuit. That feature was not shown in any of Bell's patent drawings, but was shown in Elisha Gray's drawings in his caveat filed the same day, February 14, 1876. A description of the variable resistance feature, consisting of seven sentences, was inserted into Bell's application. That it was inserted is not disputed. But when it was inserted is a controversial issue. Bell testified that he wrote the sentences containing the variable resistance feature before January 18, 1876, "almost at the last moment" before sending his draft application to his lawyers. A book by Evenson[79] argues that the seven sentences and claim 4 were inserted, without Bell's knowledge, just before Bell's application was hand carried to the Patent Office by one of Bell's lawyers on February 14, 1876.

Contrary to the popular story, Gray's caveat was taken to the US Patent Office a few hours before Bell's application. Gray's caveat was taken to the Patent Office in the morning of February 14, 1876, shortly after the Patent Office opened and remained near the bottom of the in-basket until that afternoon. Bell's application was filed shortly before noon on February 14 by Bell's lawyer who requested that the filing fee be entered immediately onto the cash receipts blotter and Bell's application was taken to the Examiner immediately. Late in the afternoon, Gray's caveat was entered on the cash blotter and was not taken to the Examiner until the following day. The fact that Bell's filing fee was recorded earlier than Gray's led to the myth that Bell had arrived at the Patent Office earlier.[80] Bell was in Boston on February 14 and did not know this happened until later. Gray later abandoned his caveat and did not contest Bell's priority. That opened the door to Bell being granted US patent 174465 for the telephone on March 7, 1876.

Remove ads

Memorial to the invention

Summarize

Perspective

In 1906 the citizens of the City of Brantford, Ontario, Canada and its surrounding area formed the Bell Memorial Association to commemorate the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell in July 1874 at his parents' home, Melville House, near Brantford.[81][82] Walter Allward's design was the unanimous choice from among 10 submitted models, winning the competition. The memorial was originally to be completed by 1912 but Allward did not finish it until five years later. The Governor General of Canada, Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire, ceremoniously unveiled the memorial on October 24, 1917.[81][82]

Allward designed the monument to symbolize the telephone's ability to overcome distances.[82] A series of steps lead to the main section where the floating allegorical figure of Inspiration appears over a reclining male figure representing Man, discovering his power to transmit sound through space, and also pointing to three floating figures, the messengers of Knowledge, Joy, and Sorrow positioned at the other end of the tableau. Additionally, there are two female figures mounted on granite pedestals representing Humanity positioned to the left and right of the memorial, one sending and the other receiving a message.[81]

The Bell Telephone Memorial's grandeur has been described as the finest example of Allward's early work, propelling the sculptor to fame. The memorial itself has been used as a central fixture for many civic events and remains an important part of Brantford's history, helping the city style itself as 'The Telephone City'.

Remove ads

See also

- History of the telephone

- The Telephone Cases, U.S. patent dispute and infringement court cases

- Timeline of the telephone

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads