Indigenous peoples of the Philippines

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

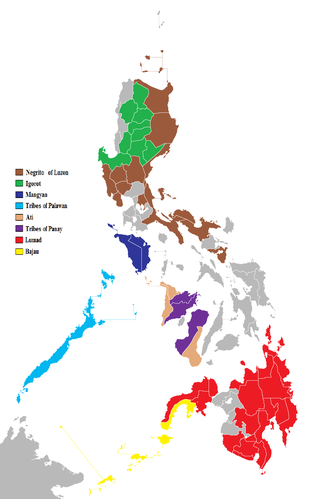

The indigenous peoples of the Philippines are ethnolinguistic groups or subgroups that maintain partial isolation or independence throughout the colonial era, and have retained much of their traditional pre-colonial culture and practices.[1]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

The Philippines has 110 enthnolinguistic groups comprising the Philippines' indigenous peoples; as of 2010, these groups numbered at around 14–17 million persons.[2] Austronesians make up the overwhelming majority, while full or partial Negritos scattered throughout the archipelago. The highland Austronesians and Negrito have co-existed with their lowland Austronesian kin and neighbor groups for thousands of years in the Philippine archipelago.

Culturally-indigenous peoples of northern Philippine highlands can be grouped into the Igorot (comprising many different groups) and singular Bugkalot groups, while the non-Muslim culturally-indigenous groups of mainland Mindanao are collectively called Lumad. Australo-Melanesian groups throughout the archipelago are termed Aeta, Ita, Ati, Dumagat, among others. Numerous culturally-indigenous groups also live outside these two indigenous corridors.[3] In addition to these labels, groups and individuals sometimes identify with the Tagalog term katutubo, which denotes any person of indigenous origin.[4][5][6]

According to the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, there are 135 recognized local indigenous Austronesian languages in the Philippines, of which one (Tagalog) is vehicular and each of the remaining 134 is vernacular.[citation needed]

Terminology

Summarize

Perspective

Chapter II, Section 3h of the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997 defines "indigenous peoples" (IPs) and "indigenous cultural communities" (ICCs) as:

A group of people or homogenous societies identified by self-ascription and ascription by others, who have continuously lived as organized community on communally bounded and defined territory, and who have, under claims of ownership since time immemorial, occupied, possessed and utilized such territories, sharing common bonds of language, customs, traditions and other distinctive cultural traits, or who have, through resistance to political, social and cultural inroads of colonization, non-indigenous religions and cultures, became historically differentiated from the majority of Filipinos.

ICCs/IPs shall likewise include peoples who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, at the time of conquest or colonization, or at the time of inroads of non-indigenous religions and cultures, or the establishment of present state boundaries, who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions, but who may have been displaced from their traditional domains or who may have resettled outside their ancestral domains;

— Republic Act No. 8371 (October 29, 1997), The Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997, archived from the original on July 20, 2017, retrieved April 1, 2023 – via Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines

Demographics

This section needs to be updated. (June 2024) |

Indigenous people make up 10% and 20% of the population of the Philippines, based on the 2020 census.[7]

Because they displayed a variety of social organization, cultural expression and artistic skills. They showed a high degree of creativity, usually employed to embellish utilitarian objects, such as bowls, baskets, clothing, weapons and spoons. The tribal groups of the Philippines are known for their carved wooden figures, baskets, weaving, pottery and weapons.

Ethnic groups

Summarize

Perspective

Northern Philippines

Indigenous peoples in Northern Luzon are found mostly in the Cordillera Administrative Region, where various Igorot groups such as Bontoc, Ibaloi, Ifugao, Isneg, Kalinga, Kankanaey, Tinguian, Karao, and Kalanguya exist. Other indigenous groups living in the Cordillera's adjacent regions are the Gaddang of Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela; Ilongot of Nueva Vizcaya and Nueva Ecija, and Aurora; Isinay, primarily of Nueva Vizcaya; Aeta of Zambales, Tarlac, Pampanga, Bataan, Nueva Ecija; and the Ivatan of Batanes.[8] Many of these indigenous groups cover a wide spectrum in terms of their integration and acculturation with lowland Christian Filipinos. Native groups such as the Bukidnon in Mindanao, had intermarried with lowlanders for almost a century. Other groups such as the Kalinga in Luzon have remained isolated from lowland influence.

There were several upland groups living in the Cordillera Central of Luzon in 1990. At one time it was employed by lowland Filipinos in a pejorative sense, but in recent years it came to be used with pride by native groups in the mountain region as a positive expression of their ethnic identity. The Ifugao of Ifugao province, the Bontoc, Kalinga, Tinguian, Kankanaey and Ibaloi were all farmers who constructed the rice terraces for many centuries.

Other mountain peoples of Luzon such as the Isnag of Apayao, the Gaddang of the border between Kalinga and Isabela provinces, and the Ilongot Nueva Vizcaya and Caraballo Mountains all developed hunting and gathering, farming cultivation and headhunting. Other groups such as the Negritos formerly dominated the highlands throughout the islands for thousands of years, but have been reduced to a small population, living in widely scattered locations, primarily along the eastern ranges of the mountains.

Central Philippines

Upland and lowland indigenous groups are concentrated on western Visayas, although there are several upland groups such as the Mangyan living in Mindoro.

Palawan, the largest province in the Philippines, is home to several indigenous ethnolinguistic groups namely, the Kagayanen, Tagbanwa, Palawano, Taaw't Bato, Molbog, and Batak tribes.[9] They live in remote villages in the mountains and coastal areas.[9][10]

Southern Philippines

Among the most important indigenous groups in Mindanao are collectively called the Lumad. These include the Manobo; the Talaandig, Higaonon and Bukidnon people of Bukidnon; the Bagobo, Mandaya, Mansaka, Tagakaulo of the Davao Region who inhabit the mountains bordering Davao Gulf; the Kalagan people who live in lowland areas and seashores of Davao del Norte, Compostela Valley, Davao Oriental and some seashores in Davao del Sur; the Subanon of upland areas in Zamboanga; the Mamanwa in the Agusan-Surigao border region; and the B'laan, Teduray and Tboli of the region of Cotabato.[11][12]

The Manobo is a large ethnographic group and includes the Ata-Manobo and the Matigsalug of Davao City, Davao del Norte and Bukidnon; the Langilan-Manobo in Davao del Norte; the Agusan-Manobo in Agusan del Sur and southern parts of Agusan del Norte; the Pulanguiyon-Manobo of Bukidnon; the Ubo-Manobo in southwestern parts of Davao City, and northern parts of Cotabato; the Arumanen-Manobo of Carmen, Cotabato; and the Dulangan-Manobo in Sultan Kudarat.[11]

The Yakan is the major indigenous peoples of the Sulu Archipelago and live primarily in the hinterlands of Basilan. The Sama Banguingui live in the lowlands of Sulu, while the nomadic Luwa'an live in coastal areas. The Sama or the Sinama and the Jama Mapun are the indigenous peoples of Tawi-Tawi.[12][11]

Ancestral domain

Summarize

Perspective

In the Philippines, the term ancestral domain refers to indigenous peoples' land rights in law.[13] Ancestral lands are referred to in the Philippines Constitution. Article XII, Section 5 says: "The State, subject to the provisions of this Constitution and national development policies and programs, shall protect the rights of indigenous cultural communities to their ancestral lands to ensure their economic, social, and cultural well-being."[14]

The Indigenous People's Rights Act of 1997 recognizes the right of Indigenous peoples to manage their ancestral domains.[15] The law defines ancestral domain to include lands, inland waters, coastal areas, and natural resources owned or occupied by Indigenous peoples, by themselves or through their ancestors.[16] The law requires the involvement of indigenous peoples in the development process through the principle of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).[17][18]

The law also tasks the government to issue Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADTs) and Certificate of Ancestral Land Title (CALTs) in recognition of indigenous peoples' rights to their land, cultural integrity, self-governance, and social justice.[19] As of 2023, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples reported having issued only 33% of its targeted 1,531 Certificate of Ancestral Domain Titles and Certificate of Ancestral Land Titles.[20]

The Philippines is a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[19]

The Food and Agriculture Organization's research on forest land ownership in the Philippines found conflicts in institutional mandates among the Local Government Code, mining law and the National Integrated Protected Areas Act, and recommended exclusive resource use rights to community-based forest management communities.[21]

In the 2022 State of the Indigenous Peoples Address Report, the Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center states that 1.25 million hectares of indigenous lands are threatened by destructive projects that will cause massive ecological disturbance, including biodiversity loss and air, water, and land pollution.[22]

Biodiversity

According to a 2017 estimate by the Philippine Association for Inter-Cultural Development, ancestral domains cover 85% of the key biodiversity areas in the Philippines.[23] Indigenous leadership and knowledge help protect habitat areas, some of which are considered sacred grounds.[19] Biodiversity in these areas are threatened by habitat loss owing to poor infrastructure development, unsustainable tourism, and the weakening of indigenous leadership.[23]

The 2018 Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act, which contains the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Conserved Areas and Territories Declaration, authorizes indigenous communities to "govern, maintain, develop, protect and conserve such areas in accordance to their indigenous knowledge, systems, practices and customary laws with full and effective assistance from NCIP, DENR, and other concerned government agencies".[23]

Natural resources

Ancestral lands make up 13 million to 14 million hectares of the Philippines' lands area, including 5.3 million hectares of forest land.[22] More than 50% bauxite, nickel, and other mineral deposits in the Philippines are on ancestral lands, according to a 2022 estimate.[24]

Energy resources

Many energy projects are on Indigenous lands. In the Cordillera region, as of 2024, there are 100 renewable energy projects, including projects that will affect Indigenous Community Conservation Areas and biodiversity hotspots.[7] In Iloilo, the Jalaur River megadam project is adversely affecting Tumandok Indigenous lands and communities.[7]

Chico River Dam Project

The Chico River Dam Project was a proposed hydroelectric power generation project involving the Chico River on the island of Luzon in the Philippines that locals, notably the Kalinga people, resisted because of its threat to their residences, livelihood, and culture.[25] The project was shelved in the 1980s after public outrage in the wake of the murder of opposition leader Macli-ing Dulag. It is now considered a landmark case study concerning ancestral domain issues in the Philippines.[26][27]

Community schools

Summarize

Perspective

The 1987 Philippine Constitution provides for recognizing and promoting indigenous learning systems under Article XIV, Section 2, Paragraph 1.[28] The Department of Education (DepEd) recognized community schools through the National Indigenous Peoples Education Policy Framework (DepEd Order No. 62 s. 2011), signed by DepEd Secretary Armin Luistro in 2012.[29] The Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education supports the framework as a priority program to help sustain cultural traditions and knowledge.[30]

The Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 incorporates the Indigenous Peoples Education (IPEd) Curriculum Framework, which promotes indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSP) and supports indigenous peoples' rights to an education that is culturally appropriate and responsive to indigenous educational, social, and environmental contexts.[31]

DepEd issued in 2014 the Guidelines on the Recognition of Private Learning Institutions Serving Indigenous Peoples Learners (DepEd Order 21 s. 2014), which recognizes Indigenous Peoples Education (IPEd) and the private and nongovernment organizations that provide culture-based education,[32] as well as Guidelines on the Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous Peoples Culture (DepEd Order 51, s. 2014).[33]

In February 2016, the DepEd announced that it was opening 251 schools for 22 indigenous cultural communities in Davao, the Zamboanga peninsula, Northern Mindanao, and the Soccsksargen and Caraga regions. The schools will be able to take in 19,600 students. The DepEd will hire 583 teachers, construct 605 classrooms,[34] and develop 500 lesson plans. As of August 2016, 7,700 public school teachers had undergone training on implementing IPEd.[35]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.