Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus

Exodus of Hindus from the Kashmir Valley in the 1990s From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus,[note 2] or Pandits, is their early-1990[1][2] migration,[19] or flight,[20] from the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley in Indian-administered Kashmir following rising violence in an insurgency. Of a total Pandit population of 120,000–140,000 some 90,000–100,000 left the valley[3][5][4][7] in February and March 1990,[21][note 3] by which time about 30–80 of them are said to have been killed by militants.[7][12][13]

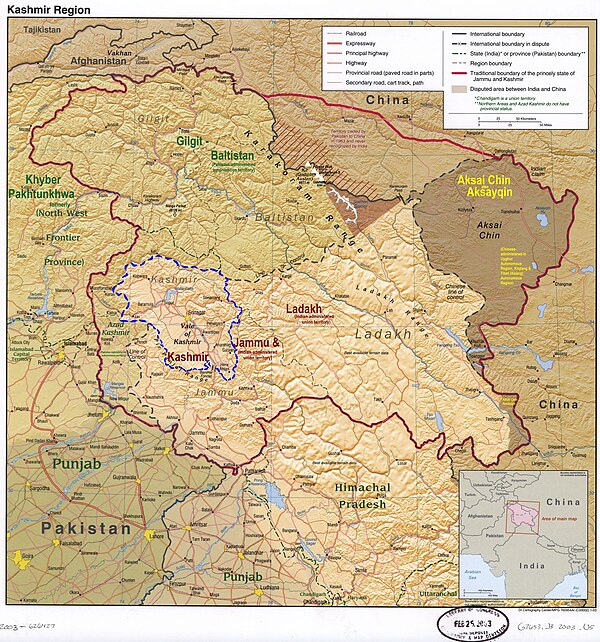

Political map of the disputed Kashmir region showing the Kashmir Valley or Vale of Kashmir, in the Indian-administered Kashmir division (in neon blue), from which a large proportion of Hindus have migrated out | |

| Date | Early 1990.[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Location | Kashmir Valley, Indian-administered Kashmir |

| Coordinates | 34.0333°N 74.6667°E |

| Outcome | |

| Deaths |

|

During the period of substantial migration, the insurgency was being led by a group calling for a secular and independent Kashmir, but there were also growing Islamist factions demanding an Islamic state.[24][25][26] Although their numbers of dead and injured were low,[27] the Pandits, who believed that Kashmir's culture was tied to India's,[6][28] experienced fear and panic set off by targeted killings of some members of their community—including high-profile officials among their ranks—and public calls for independence among the insurgents.[29] The accompanying rumours and uncertainty together with the absence of guarantees for their safety by the state government might have been the latent causes of the exodus.[30][31] The descriptions of the violence as "genocide" or "ethnic cleansing" in some Hindu nationalist publications or among suspicions voiced by some exiled Pandits are widely considered inaccurate and aggressive by scholars.[32][33][34][35]

The reasons for this migration are vigorously contested. In 1989–1990, as calls by Kashmiri Muslims for independence from India gathered pace, many Kashmiri Pandits, who viewed self-determination to be anti-national, felt under pressure.[36] The killings in the 1990s of a number of Pandit officials, may have shaken the community's sense of security, although it is thought some Pandits—by virtue of their evidence given later in Indian courts—may have acted as agents of the Indian state.[37] The Pandits killed in targeted assassinations by the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) included some high-profile ones.[38] Occasional anti Hindu calls were made from mosques on loudspeakers asking Pandits to leave the valley.[39][40] News of threatening letters created fear,[41] though in later interviews the letters were seen to have been sparingly received.[42] There were disparities between the accounts of the two communities, the Muslims and the Pandits.[43] Many Kashmiri Pandits believed they were forced out of the Valley either by Pakistan and the militants it supported or the Kashmiri Muslims as a group.[44] Many Kashmiri Muslims did not support violence against religious minorities; the departure of the Kashmiri Pandits offered an excuse for casting Kashmiri Muslims as Islamic radicals,[45] thereby contaminating their more genuine political grievances,[46] and offering a rationale for their surveillance and violent treatment by the Indian state.[47] Many Muslims in the Valley believed that the then Governor, Jagmohan had encouraged the Pandits to leave so as to have a free hand in more thoroughly pursuing reprisals against Muslims.[48][49] Several scholarly views chalk up the migration to genuine panic among the Pandits that stemmed as much from the religious vehemence among some of the insurgents as by the absence of guarantees for the Pandits' safety issued by the Governor.[26][50]

Kashmiri Pandits initially moved to the Jammu Division, the southern half of Jammu and Kashmir, where they lived in refugee camps, sometimes in unkempt and unclean surroundings. At the time of their exodus, very few Pandits expected their exile to last beyond a few months.[51] As the exile lasted longer, many displaced Pandits who were in the urban elite were able to find jobs in other parts of India, but those in the lower-middle-class, especially those from rural areas languished longer in refugee camps, with some living in poverty; this generated tensions with the host communities—whose social and religious practices, although Hindu, differed from those of the brahmin Pandits—and rendered assimilation more difficult.[52] Many displaced Pandits in the camps succumbed to emotional depression and a sense of helplessness.[53] The cause of the Kashmiri Pandits was quickly championed by right-wing Hindu groups in India,[54] which also preyed on their insecurities and further alienated them from Kashmiri Muslims.[55] Some displaced Kashmiri Pandits have formed an organization called Panun Kashmir ("Our own Kashmir"), which has asked for a separate homeland for Kashmiri Hindus in the Valley but has opposed autonomy for Kashmir on the grounds that it would promote the formation of an Islamic state.[56] The return to the homeland in Kashmir also constitutes one of the main points of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party's election platform.[57][note 4] Although discussions between the Pandits and the Muslims have been hampered by the insistence on the part of each of their deprivation, and a rejection of the other's suffering, the Pandits who have left Kashmir have felt separated and obliterated.[58] Kashmiri Pandits in exile have written autobiographical memoirs, novels, and poetry to record their experiences and to understand them.[59] 19 January is observed by the Kashmiri Hindu communities as Exodus Day.[60][61]

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The Kashmir Valley, which is a part of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan from 1947, has been administered by India from approximately the same time.[62][63] Before 1947, during the period of British Raj in India when Jammu and Kashmir was a princely state, Kashmiri Pandits, or Kashmiri Hindus, had stably constituted between 4% and 6% of the population of the Kashmir valley in censuses from 1889 to 1941; the remaining 94% to 96% were Kashmir valley's Muslims, overwhelmingly followers of Sunni Islam.[64][65][66][67][68] These Muslims had the self-assured awareness of a predominant community; their support was considered consequential in a determination of Kashmir's future.[69] By 1950, in the face of Kashmir's princely ruler's unresolved accession to India, the land reforms planned by the incoming administration of Sheikh Abdullah, and the threat of socio-economic decline, a large number of Pandits—whose elite owned over 30% of the arable land in the Valley—moved to other parts of India.[70][71]

In 1989 a persisting insurgency began in Kashmir. It was fed by Kashmiri dissatisfaction with India's federal government over rigging an assembly election in 1987 and disavowing a promise of greater autonomy. The dissatisfaction overflowed into an ill-defined uprising against the Indian state. The Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), an organization that had generally secular antecedents and the predominant goal of political independence,[6][25][72] led the uprising but did not abjure violence.[73][74] In early 1990, the vast majority of Kashmiri Hindus fled the valley in a mass-migration.[75][72][76][note 5][note 6] More of them left in the following years so that, by 2011, only around 3,000 families remained.[8] 30 or 32 Kashmiri Pandits had been killed by insurgents by mid-March 1990 when the exodus was largely complete, according to some scholars.[7][12] Indian Home Ministry data records 217 Hindu civilian fatalities during the four-year period, 1988 to 1991.[14][note 7]

Under the 1975 Indira–Sheikh Accord, Sheikh Abdullah agreed to measures previously undertaken by the central government in Jammu and Kashmir to integrate the state into India.[79] Farrukh Faheem, a sociologist at the University of Kashmir, states that it was met with hostility among the people of Kashmir and laid the groundwork for the future insurgency.[80] Those opposed to the accords included Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir, People's League in Indian Jammu and Kashmir, and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) based in Pakistani-administered Azad Jammu and Kashmir.[81] Since the mid-1970s, communalist rhetoric was being exploited in the state for votebank politics. Around this time, Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) tried to spread Wahhabism in place of Sufism to foster religious unity within their nation, and the communalization aided their cause.[82] Islamization of Kashmir began in the 1980s when Sheikh Abdullah's government changed the names of about 300 places to Islamic names.[83][note 8] Sheikh also started delivering communal speeches in mosques that were similar to his confrontational pro-independence speeches in the 1930s. Additionally, he referred to Kashmiri Hindus as mukhbir (Hindustani: मुख़बिर, مخبر), or informants of the Indian military.[85][86][better source needed]

The ISI's initial attempts to sow widespread unrest in Kashmir against the Indian administration were largely unsuccessful until the late-1980s.[87] The American- and Pakistani-backed Afghan mujahideen's armed struggle against the Soviet Union in the Soviet–Afghan War, the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the Sikh insurgency in Indian Punjab against the Indian government became sources of inspiration for large numbers of Kashmiri Muslim youth.[88][89] Both the pro-independence JKLF and pro-Pakistan Islamist groups including Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir mobilized the rapidly-growing anti-Indian sentiments amongst the Kashmiri population; the year of 1984 saw a pronounced rise in terrorist violence in Kashmir. Following the execution of JKLF militant Maqbool Bhat in February 1984, strikes and protests by Kashmiri nationalists broke out in the region, where large numbers of Kashmiri youth participated in widespread anti-India demonstrations and consequently faced heavy-handed reprisals by state security forces.[90][91]

Critics of the then chief minister, Farooq Abdullah, charged him with losing control of the situation. His visit to Pakistani-administered Kashmir during this time became an embarrassment, where according to JKLF's Hashim Qureshi, he shared a platform with the JKLF.[92] Abdullah asserted that he went on behalf of Indira Gandhi and his father, so that sentiments there could "be known first hand", although few people believed him. There were also allegations that he had allowed Khalistani militants to train in Jammu, although these were never proved to be true. On 2 July 1984, Ghulam Mohammad Shah, who had support from Indira Gandhi, replaced his brother-in-law Farooq Abdullah and assumed the role of chief minister after Abdullah was dismissed, in what was termed a "political coup".[91]

G. M. Shah's administration, which did not have people's mandate, turned to Islamists and opponents of India, notably the Molvi Iftikhar Hussain Ansari, Mohammad Shafi Qureshi and Mohinuddin Salati, to gain some legitimacy through religious sentiments. This gave political space to Islamists who previously lost overwhelmingly in the 1983 state elections.[91] In 1986, Shah decided to construct a mosque within the premises of an ancient Hindu temple inside the New Civil Secretariat area in Jammu to be made available to the Muslim employees for 'Namaz'. People of Jammu took to streets to protest against this decision, which led to a Hindu-Muslim clash.[93] In February 1986, Shah on his return to Kashmir valley retaliated and incited the Kashmiri Muslims by saying Islām khatre mẽ hai (transl. Islam is in danger). As a result, this led to the 1986 Kashmir riots where Kashmiri Hindus were targeted by the Kashmiri Muslims. Many incidents were reported in various areas where Kashmiri Hindus were killed and their properties and temples damaged or destroyed. The worst hit areas were mainly in South Kashmir and Sopore. During the Anantnag riot in February 1986, although no Hindu was killed, many houses and other properties belonging to Hindus were looted, burnt or damaged.[94] An investigation of Anantnag riots revealed that members of the 'secular parties' in the state, rather than the Islamists, had played a key role in organising the violence to gain political mileage through religious sentiments. Shah called in the army to curb the violence, but it had little effect. His government was dismissed on 12 March 1986, by Governor Jagmohan following communal riots in south Kashmir, and led to Governor's rule in the state. The political fight was hence being portrayed as a conflict between "Hindu" New Delhi (Central Government), and its efforts to impose its will in the state, and "Muslim" Kashmir, represented by political Islamists and clerics.[95]

For the 1987 state elections, various Islamist groups, including Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir, organised themselves under the banner of Muslim United Front, with a manifesto to work for Islamic unity and against political interference from the centre. The two mainstrain parties (NC and INC) were allied together and won the election, However, the elections are widely believed to have been rigged in favour of the mainstream alliance and thus the government formed by Farooq Abdullah lacked legitimacy.[96] The corruption and alleged electoral malpractices were the catalysts for an insurgency.[97][98][99] The Kashmiri militants killed anyone who openly expressed pro-India policies. Kashmiri Hindus were targeted specifically because they were seen as presenting Indian presence in Kashmir because of their faith.[100] Though the insurgency had been launched by JKLF, groups rose over the next few months advocating for establishment of Nizam-e-Mustafa (administration based on Sharia) on Islamist groups proclaimed the Islamicisation of socio-political and economic set-up, merger with Pakistan, unification of ummah and establishment of an Islamic Caliphate. Liquidation of central government officials, Hindus, liberal and nationalist intellectuals, social and cultural activists was described as necessary to rid the valley of un-Islamic elements.[101][102] The relations among the mainstream parties and Islamist groups were generally poor and often hostile. The JKLF had also utilized Islamic formulations in its mobilization strategies and public discourse, using Islam and independence interchangeably. It demanded equal rights for everyone, however this had a distinct Islamic flavour as it sought to establish an Islamic democracy, protection of minority rights per Quran and Sunnah and an economy of Islamic socialism. The pro-separatist political practices at times deviated from their stated secular position.[103][104]

Insurgency activity

Summarize

Perspective

In July 1988, the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) began a separatist insurgency for secession of Kashmir from India.[105] The group targeted a Kashmiri Hindu for the first time on 14 September 1989, when they killed Tika Lal Taploo, an advocate and a prominent leader of Bharatiya Janata Party in Jammu and Kashmir, in front of several eyewitnesses.[106][107] This instilled fear in the Kashmiri Hindus especially as Taploo's killers were never caught which also emboldened the terrorists. The Hindus felt that they were not safe in the valley and could be targeted any time. The killings of Kashmiri Hindus, including many prominent ones, instilled more fear.[108][better source needed]

In order to undermine his political rival Farooq Abdullah who at that time was the Chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian home minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed convinced prime minister V.P. Singh to appoint Jagmohan as the governor of the state. Abdullah resented Jagmohan who had been appointed as the governor earlier in April 1984 as well and had recommended Abdullah's dismissal to Rajiv Gandhi in July 1984. Abdullah had earlier declared that he would resign if Jagmohan was made the Governor. However, the Central government went ahead and appointed him as Governor. In response, Abdullah resigned on 18 January 1990, and Jagmohan suggested the dissolution of the State Assembly.[109]

Most of the Kashmiri Hindus left Kashmir valley and moved to other parts of India, particularly to the refugee camps in Jammu region of the state.[110]

Attack and threats

On 14 September 1989, Tika Lal Taploo, who was a lawyer and a BJP member, was murdered by the JKLF in his home in Srinagar.[107][106]

On 4 November, a judge Neelkanth Ganjoo, was shot dead near the Srinagar High court. He had sentenced Kashmiri separatist Maqbool Bhat to death in 1968.[106][111][112]

In December, members of JKLF kidnapped Dr. Rubaiya Sayeed, daughter of the-then Union Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, demanding release of five militants, which was subsequently fulfilled.[113][114][115]

On 4 January 1990, Srinagar-based newspaper Aftab released a message, threatening all Hindus to leave Kashmir immediately, sourcing it to the militant organization Hizbul Mujahideen.[116][117][118][unreliable source?] On 14 April 1990, another Srinagar based newspaper Al-safa republished the same warning.[106][119] The newspaper did not claim ownership of the statement and subsequently issued a clarification.[116][117] Walls were pasted with posters with threatening messages to all Kashmiris to strictly follow Islamic rules[120] which included abidance by the Islamic dress code, a prohibition on alcohol, cinemas, and video parlors[121] and strict restrictions on women.[122] Unknown masked men with Kalashnikovs forced people to reset their time to Pakistan Standard Time. Offices buildings, shops, and establishments were colored green as a sign of Islamic rule.[118][123] Shops, factories, temples and homes of Kashmiri Hindus were burned or destroyed. Threatening posters were posted on doors of Hindus asking them to leave Kashmir immediately.[118][124] During the middle of the night of 18 and 19 January, a blackout took place in the Kashmir Valley where electricity was cut except in mosques[citation needed] which broadcast divisive and inflammatory messages, asking for a purge of Kashmiri Hindus.[125][126][better source needed]

On 21 January, two days after Jagmohan took over as governor, the Gawkadal massacre took place in Srinagar, in which the Indian security forces had opened fire on protesters, leading to the death of at least 50 people, and likely over 100. These events led to chaos. Lawlessness took over the valley and the crowd with slogans and guns started roaming around the streets. News of violent incidents kept coming and many of the Hindus who survived the night saved their lives by traveling out of the valley.[127][128][105]

On 25 January, the Rawalpora shooting incident took place, wherein four Indian Air Force personnel, Squadron Leader Ravi Khanna, Corporal D.B. Singh, Corporal Uday Shankar and Airman Azad Ahmad were killed and 10 other IAF personal were injured, while they were waiting at Rawalpora bus stand for their vehicle to pick them up in the morning. Altogether around 40 rounds were fired by the terrorists, apparently from 2 to 3 automatic weapons and one semi-automatic pistol. The Jammu and Kashmir Armed Police post located nearby, with 7 armed constables and one head constable, did not react. Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), with its leader Yasin Malik in particular, were allegedly involved in the killings. Incidents like these further expedited the exodus of Hindus from Kashmir.[129][130][131][132]

Several intelligence operatives were assassinated, over the course of January.[133][115]

On 2 February, Satish Tikoo, a young Hindu social worker was murdered near his own house in Habba Kadal, Srinagar.[106][134]

On 13 February, Lassa Kaul, Station Director of Srinagar Doordarshan, was shot dead.[106][135]

On 29 April, Sarwanand Koul Premi, a veteran Kashmiri poet and his son were shot and hanged.[136]

On 4 June, Girija Tickoo, a Kashmiri Hindu teacher was gang raped by terrorists, who ripped her abdomen and chopped her body into two pieces with a saw machine while she was still alive.[137]

Many Kashmiri Pandit women were kidnapped, raped and murdered, throughout the time of exodus.[138][121] The local organisation of Hindus in Kashmir, Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti (KPSS), after carrying out a survey in 2008 and 2009, estimated 357 Hindus were killed in Kashmir in 1990.[139]

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

Militancy in Kashmir increased after the exodus, and militants targeted properties of Kashmiri Hindus.[140][141] Indian Home Ministry data records 1,406 Hindu civilian fatalities from 1991 to 2005.[14] Jammu and Kashmir government stated that 219 members of the Hindu Pandit community had been killed between 1989 and 2004 and none thereafter.[16][142] The local organisation of Hindus in Kashmir, Kashmir Pandit Sangharsh Samiti (KPSS) after carrying out a survey in 2008 and 2009, said that 399 Kashmiri Hindus were killed by insurgents from 1990 to 2011 with 75% of them being killed during the first year of the Kashmiri insurgency, and that during the last 20 years, about 650 Hindus have been killed in the valley.[143][144]

In response to the exodus, an organisation Panun Kashmir, a political group representing the Hindus who fled Kashmir, was formed. In late 1991, the organisation adopted the Margdarshan Resolution, which stated the need for a separate Union Territory in Kashmir division, Panun Kashmir. Panun Kashmir would serve as a homeland for Kashmiri Hindus and would resettle the displaced Kashmiri Pandits.[145]

In 2009 Oregon Legislative Assembly passed a resolution to recognise 14 September 2007, as Martyrs Day to acknowledge ethnic cleansing and campaigns of terror inflicted on non-Muslim minorities of Jammu and Kashmir by militants seeking to establish an Islamic state.[146]

Kashmiri Hindus continue to fight for their return to the valley and many of them live as refugees.[147] The exiled community had hoped to return after the situation improved. Most have not done so because the situation in the Valley remains unstable and they fear a risk to their lives. Most of them lost their properties after the exodus and many are unable to go back and sell them. Their status as displaced people has adversely harmed them in the realm of education. Many Hindu families could not afford to send their children to well regarded public schools. Furthermore, many Hindus faced institutional discrimination by predominantly Muslim state bureaucrats. As a result of the inadequate ad hoc schools and colleges formed in the refugee camps, it became harder for Hindu children to access education. They suffered in higher education as well, as they could not claim admission in PG colleges of Jammu university, while getting admitted in the institutes of Kashmir valley was out of question.[148]

During the 2016 Kashmir unrest following the killing of Burhan Wani, transit camps housing Kashmir Hindus in Kashmir were attacked by mobs.[149] About 200–300 Kashmiri Hindu employees fled the transit camps during night time on 12 July due to the attacks, and held protests against the government for attacks on their camp and demanded that all Kashmiri Hindus employees in Kashmir valley be evacuated immediately. Over 1300 government employees belonging to the community had fled the region during the unrest.[150][151][152] Posters threatening the Hindus to leave Kashmir or be killed were also put up near transit camps in Pulwama allegedly by the militant organisation Lashkar-e-Toiba.[153][154]

An organisation called Roots of Kashmir filed a petition in 2017 to reopen 215 cases of more than 700 alleged murders of Kashmiri Hindus, however the Supreme Court of India refused its plea.[155] They have also demanded the creation of a "special crimes tribunal" to look into the ethnic cleansing and crimes committed. They also demanded a one time compensation for displaced Kashmiri Hindus who are not able to apply for government jobs.[156]

Rehabilitation

Summarize

Perspective

The Indian Government has tried to rehabilitate the Hindus and the separatists have also invited the Hindus back to Kashmir.[157]

As of 2016, a total of 1,800 Kashmiri Hindu youths have returned to the Valley since the announcing of Rs. 1,168-crore package in 2008 by the UPA government. However, R.K. Bhat, president of Youth All India Kashmiri Samaj criticised the package to be a mere eyewash and claimed that most of the youths were living in cramped prefabricated sheds or in rented accommodation. He also said that 4,000 posts have been lying vacant since 2010 and alleged that the BJP government was repeating the same rhetoric and was not serious about helping them. The apathy on the part of the government and the sufferings of the Kashmiri Hindus have been highlighted in a play titled 'Kaash Kashmir'.[158] Such efforts or claims have lacked political will as journalist Rahul Pandita writes in a memoir.[159]

In an interview with NDTV on 19 January, Farooq Abdullah created controversy when he stated that the onus was on Kashmiri Hindus to come back themselves and nobody would beg them to do so. His comments were met with disagreement and criticism by Kashmiri Hindu authors Neeru Kaul, Siddhartha Gigoo, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor and Lt. General Syed Ata Hasnain (retd.). He also said that during his tenure as Chief Minister in 1996, he had asked them to return but they refused to do so. He reiterated his comments on 23 January and said that the time had come for them to return.[160][161][162][163]

The issue of separate townships for Kashmiri Hindus has been a source of contention in the Kashmir valley, with Islamists, separatists, as well as mainstream political parties, all opposing it.[164] Hizbul Mujahideen militant, Burhan Muzaffar Wani, had threatened of attacking the "Hindu composite townships" which were meant to be built for the rehabilitation of the non-Muslim community. In a 6-minute long video clip, Wani described the rehabilitation scheme as resembling Israeli designs.[165] Kashmiri Hindus residing in the Valley also mourned Burhan Wani's death.[166] Burhan Wani's self-styled successor in the Hizbul Mujahideen, Zakir Rashid Bhat, also asked the Kashmiri Hindus to return and ensured them protection.[167][168]

In 2010, the Government of Jammu and Kashmir noted that 808 Hindus families, comprising 3,445 people, were still living in the Valley and that financial and other incentives put in place to encourage others to return there had been unsuccessful.[16] The employment package was also extended to Hindus who did not migrate out of the valley with an amendment to J&K Migrants (Special Drive) Recruitment Rules, 2009 in October 2017.[169] The Indian Government has taken up the issue of education of the displaced students from Kashmir, and helped them get admissions in various Kendriya Vidyalayas and major educational institutions & universities across the country.

Some consider the now-abrogated Article 370 as a roadblock in the resettlement of Kashmiri Hindus as the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir does not allow those living in India outside Jammu and Kashmir to freely settle in the state and become its citizens.[170][171][172] Sanjay Tickoo, president of Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti (KPSS), says that the 'Article 370' affair is different from the issue of exodus of Kashmiri Hindus and both should be dealt with separately. He remarks that, linking both the affairs is an "utterly insensitive way to deal with a highly sensitive and emotive issue"[citation needed]

In popular culture

Books

- Our Moon Has Blood Clots, 2013 book by Indian journalist Rahul Pandita is based on the firsthand account of the exodus.

- A Long Dream of Home – The persecution, exile and exodus of Kashmiri Pandits by Siddhartha Gigoo and Varad Sharma.

Movies

- 2020 Hindi film Shikara directed by Vidhu Vinod Chopra is based on the exodus of Kashmiri Hindus[173]

- 2022 Hindi film The Kashmir Files directed by Vivek Agnihotri[174]

See also

Notes

- Still another estimates it to be 190,000 of a total population of 200,000.[10] The CIA Factbook estimated the number to be 300,000.[11]

- Oxford English Dictionary Online defines exodus as – "The departure or going out, usually of a body of persons from a country for the purpose of settling elsewhere. Cf. 'emigration n. 2': The departure of persons from one country, usually their native land, to settle permanently in another.[18]

- Kashmiri Pandits are not considered "refugees" as they have not crossed an international border. Many Pandits would like to be considered Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), but the Indian government has denied them that status, fearing international involvement in Kashmir, which it considers to be its internal affair. The Indian government considers Kashmiri Pandits to be 'migrants.'[22][23]

- Kashmiri Pandits are not considered "refugees" as they have not crossed an international border. Many would like to be considered Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), but the Indian government has denied them that status, fearing international involvement in Kashmir, which it considers to be its internal affairs. The Indian government considers Kashmiri Pandits to be 'migrants.'

- Still another estimates it to be 190,000 of a total population of 200,000.[10] The CIA Factbook estimated the number to be 300,000.[11]

- Alexander Evans estimates 228 Pandit civilian fatalities, or 388 if the deaths of officials are included, but considers the higher figure of 700 to be gravely undependable[15] The 20-year Hindu civilian fatalities following 1990 have been reported by scholars quoting Kashmiri Pandit organizations within the Kashmir valley to be 650, the tally including those who were suspected by the militants to have been Indian intelligence agents.[78]

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.