Loading AI tools

American zoologist and archaeologist (1838–1925) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Edward Sylvester Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American zoologist, archaeologist, and orientalist. He is considered the "Father of Japanese archaeology."

Edward Sylvester Morse | |

|---|---|

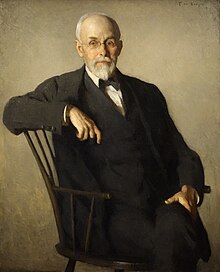

Portrait of Morse by Frank Weston Benson, 1913 (Peabody Essex Museum) | |

| Born | June 18, 1838 Portland, Maine, United States |

| Died | December 20, 1925 (aged 87) Salem, Massachusetts, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Zoologist, archaeologist, orientalist |

| Signature | |

Morse was born in Portland, Maine to Jonathan Kimball Morse and Jane Seymour (Becket) Morse.[1][2] His father was a Congregationalist deacon who held strict Calvinist beliefs. His mother, who did not share her husband's religious beliefs, encouraged her son's interest in the sciences. An unruly student, Morse was expelled from all but one of the schools he attended in his youth — the Portland village school, the academy at Conway, New Hampshire, in 1851, and Bridgton Academy in 1854 (for carving on desks). He also attended Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine. At Gould Academy, Morse came under the influence of Dr. Nathaniel True who encouraged Morse to pursue his interest in the study of nature.[3]

He preferred to explore the Atlantic coast in search of shells and snails, or go to the field to study the fauna and flora. By the age of thirteen he had put together an impressive collection of shells.[4] Despite his lack of formal education, his collections soon earned him the visit of eminent scientists from Boston, Washington and even the United Kingdom.[3] He was noted for his work with land snails, and discovered two new species: Helix asteriscus, now known as Planogyra asteriscus, and H. Milium, now known as Striatura milium.[5] These species were presented at meetings of the Boston Society of Natural History in 1857 and 1859.[6][7]

He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by Philip Pearsall Carpenter to Louis Agassiz (1807–1873) at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University for his intellectual qualities and talent at drawing. After completing his studies he served as Agassiz's assistant in charge of conservation, documentation and drawing collections of mollusks and brachiopods until 1862.[1][3] He became especially interested in brachiopods during this time, and his first paper on the topic was published in 1862.[9][10]

During the American Civil War, Morse attempted to enlist in the 25th Maine Infantry, but was turned down due to a chronic tonsil infection. On June 18, 1863, Morse married Ellen (“Nellie”) Elizabeth Owen in Portland. The couple had two children, Edith Owen Morse and John Gould Morse (named after Morse's lifelong friend Major John Mead Gould).[3]

Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in malacology or the study of molluscs. In 1864, he published his first work devoted to molluscs under the title Observations On The Terrestrial Pulmonifera of Maine.[11] Morse had been elected to the position of curator of the Portland Natural History Society, a position he hoped would become permanent. But in 1866 the Great Fire destroyed the buildings of the Society, along with much of Portland, and also the chance of a salaried position.[3] An alternative opportunity arose with the foundation of the Peabody Academy of Science in Salem. Morse returned to Massachusetts to work at the academy, along with Caleb Cooke, Alpheus Hyatt, Alpheus Spring Packard and Frederic Ward Putnam (director), all former students of Agassiz.[1][3]

In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal The American Naturalist, and Morse became one of its editors. The establishment of the Journal was very important for American Natural History. It was written by experts in the field, but aimed to be accessible to a wide readership. This aim was greatly helped by the high quality of the illustrations, many of them provided by Morse himself.[2] Morse's desire to bring natural history to a wider audience also led him to give lectures to a variety of audiences. His combination of broad knowledge, speaking skill, and ability to draw quickly on the blackboard with both hands made him a popular presenter.[1][2]

Morse continued his work on brachiopods, often considered to be his most important scientific work.[1][12] In 1869, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[13] Between 1869 and 1873 he published a series of papers on the embryology and classification of the group.[14][15][16][17][18][19] Whereas in 1865 he had accepted the majority view that placed brachiopoda within the molluscs,[20] in 1870 largely on the basis of embryological observations, he proposed that the brachiopoda should be removed from the molluscs, and placed within the annelids, a group of segmented worms.[15] Modern taxonomy agrees with the first of these propositions, but not the second, classifying molluscs, brachiopods and annelids as three separate phyla within the superphylum Lophotrochozoa.[21] Helen Muir-Wood has given an account of the history of the classification of the brachiopods that places Morse's work in its historical context.[22]

From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at Bowdoin College. In 1873 and 1874 he was a teacher at the summer school established by Agassiz on Penikese Island. Though the school only operated for a few years, several of its students went on to distinguished careers, including David Starr Jordan.[24][3] In 1874, he became a lecturer at Harvard University. In 1876, Morse was named a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences.[25] In 1877, he provided the illustrations for a book by his friend John Mead Gould, entitled How to camp out.[23][26]

During this period the issue of evolution caused much discussion and controversy. Agassiz was an opponent of evolution. He argued that the persistence of animals such as Lingula (a brachiopod) over immense periods of time, from the Silurian to the present day, with little change was "a fatal objection to the theory of gradual development".[27] However all of his students subsequently adopted evolutionary theory in various forms.[28] A clear statement of Morse's position on evolution is found in his address, as vice-president (Natural History) of the American Association for the Advancement of Science at its Buffalo NY meeting in August 1876 (reprinted under the title of What American Zoologists have done for Evolution)[29][30] He adopts a clear selectionist position, in contrast, for example, to Hyatt, who was a neo-Lamarckian.[28] He addresses the issue of human origins, and finds the evidence for "the lowly origin of man", and common ancestry with apes, convincing. He did not only express these views in a western context, but was subsequently the first to bring Darwin's theory of evolution to Japan.[31]

In June 1877 Morse first visited Japan in search of coastal brachiopods. His visit turned into a three-year stay when he was offered a post as the first professor of Zoology at the Tokyo Imperial University. He went on to recommend several fellow Americans as o-yatoi gaikokujin (foreign advisors) to support the modernization of Japan in the Meiji Era. To collect specimens, he established a marine biological laboratory at Enoshima in Kanagawa Prefecture.[2]

While looking out of a window on a train between Yokohama and Tokyo, Morse discovered the Ōmori shell mound, the excavation of which opened the study in archaeology and anthropology in Japan and shed much light on the material culture of prehistoric Japan.[32] He returned to Japan in 1882–3 to present a report of his findings to Tokyo Imperial University.[2]

Morse had much interest in Japanese ceramics, making a collection of over 5,000 pieces of Japanese pottery.[33] On his 1882-3 visit to Japan he collected clay samples as well as finished ceramics. He devised the term "cord-marked" for the sherds of Stone Age pottery, decorated by impressing cords into the wet clay. The Japanese translation, "Jōmon," now gives its name to the whole Jōmon period as well as Jōmon pottery.[34] He brought back to Boston a collection amassed by government minister and amateur art collector Ōkuma Shigenobu, who donated it to Morse in recognition of his services to Japan. These now form part of the "Morse Collection" of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The catalogue[35] is a monumental work, and still the only major work of its kind in English.[3] His collection of daily artifacts of the Japanese people is kept at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The remainder of the collection was inherited by his granddaughter, Catharine Robb Whyte via her mother Edith Morse Robb and is housed at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta, Canada.

He travelled several times to the Far East which inspired several books, with his own illustrations. Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings was published in 1885; On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles in 1892; Latrines of the East in 1893; Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes in 1903; and Japan Day by Day in 1917.

After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.[3]

In 1886 Morse became president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[4] He became Keeper of Pottery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1890. He was also a director of the Peabody Academy of Science (now part of and succeeded by the Peabody Essex Museum) in Salem[36][1][3] from 1880 to 1914. In 1898, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun (3rd class) by the Japanese government.[1][26] He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1898.[37] He became chairman of the Boston Museum in 1914, and chairman of the Peabody Museum in 1915. He was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasures (2nd class) by the Japanese government in 1922.[38]

Morse was a friend of astronomer Percival Lowell, who inspired interest in the planet Mars. Morse would occasionally journey to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, during optimal viewing times to observe the planet. In 1906, Morse published Mars and Its Mystery in defense of Lowell's controversial speculations regarding the possibility of life on Mars.[3]

He donated over 10,000 books from his personal collection to the Tokyo Imperial University. On learning that the library of the Tokyo Imperial University was reduced to ashes by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, in his will he ordered that his entire remaining collection of books be donated to Tokyo Imperial University.[citation needed]

Morse's last paper, on shell-mounds, was published in 1925.[39] He died at his home in Salem, Massachusetts in December of that year, of cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried at the Harmony Grove Cemetery.[3]

In 1872, Morse noticed that mammals and reptiles with reduced fingers lose them beginning from the sides: thumb the first and little finger the second.[40] Later researchers revealed that this is a general pattern in tetrapods (except Theropoda and Urodela): digits are reduced in the order I → V → II → III → IV, the reverse order of their appearance in embryogenesis. This trend is known as Morse's Law.[41]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.