Dacian warfare

Historical overview article From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The history of Dacian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC to 2nd century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Dacia, populated by a collection of Thracian, Ionian, and Dorian tribes.[1] It concerns the armed conflicts of the Dacian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans. Apart from conflicts between Dacians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Dacians too.

Mythological

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Tribal wars

The Dacians fought amongst each other[2] but were later united under Burebista. However, after his death[3] in 44 BC, the empire again descended into conflict culminating in a full-scale civil war. This led to the division of Burebista's empire into five separate kingdoms, severely weakening the Dacian's defensive capabilities against enemies, particularly Rome.[4] The Dacian tribes were again consolidated under Decebalus, who achieved several military victories in a series of battles with the forces of Emperor Domitian.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Domitian's Dacian War

The two punitive expeditions mounted as a border defense against raids of Moesia from Dacia in 86-87 AD ordered by the Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus (Domitian) in 87 AD, and 88 AD. The first expedition was an unmitigated disaster, and the second achieved a peace, seen as unfavorable and shameful by many in Rome.

Trajan's Dacian Wars

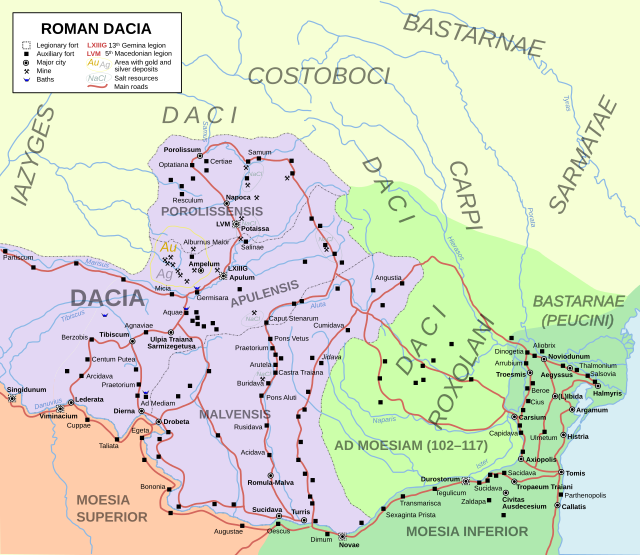

Two campaigns of conquest ordered or led by the Emperor Trajan in 101-102 AD, and 105-106 AD from Moesia across the Danube north into Dacia. Trajan's forces were successful in both cases, reducing Dacia to client state status in the first, and taking the territory over in the second. These wars involved no fewer than 13 legions.[5] The defeat reduced the Dacian territory as a mere Roman province. Rome ruled it, including the entire Transylvanian basin for 150 years. A succession of migratory waves by Visigoths, Huns, Gepids, Avars, and Slavs overran Dacia, cutting it off from the Roman and the Byzantine empires by the end of the sixth century.[1]

Dacian troop types and organization

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

The Dacians never fielded a standing army, even though there was a warrior class of sorts, the comati, meaning "long-haired people". Instead, local chieftains, the pileati, meaning "cap-wearing people", raised a levy when required, a force only available after the harvesting season ended. The men themselves fought in everyday clothing defended merely by an oval shield, for body armor and helmets were only worn by the nobility.[6]

Infantry and cavalry

The Dacian tribes established a highly militarized society and, during the periods when the tribes were united under one king (82 -44 BC, 86-106 AD), posed a major threat to the Roman provinces of Lower Danube. Julius Caesar made preparations for war with King Burebista to prevent an invasion of Macedonia, however both rulers died in the same year. Dacia lost control over territories beyond the Danube and Tisza and collapsed into hostile factions, now being able to master only 40,000 men from the previous 200,000. Dacia, however, remained a formidable foe: in the winter of 10 BC, a raid across the Danube was repulsed by Marcus Vinicius. After some decades, the invasions restarted. A major one was monitored in 69 by Licinius Mucianus while on his way to battle Aulus Vitellius. In another one in 85 the Romans almost lost Moesia, and its governor Oppius Sabinus was killed. The following year a Dacian force annihilated the army of Cornelius Fuscus under the new leader Decebalus after the victory of Tettius Julianus at Tapae. As the war dragged on, Domitian was distracted by the Suebians and Iazyges, and had to make a humiliating peace.[7] Later Trajan had attacked Decebalus two times, first making peace before reaching the capital, then taking it and conquering around a third of Dacia. According to Criton of Heraclea, 500,000 POWs were taken.[8] The Free Dacians, allying with Scythian and Germanic tribes never stopped raiding the new Roman province.

After the sound of the carnyx war trumpet, the Dacians went to battle with the draco. The most important weapon of their arsenal was the falx.[citation needed] This dreaded weapon, similar to a large sickle, came in two variants: a shorter, one-handed falx called a sica,[9] and a longer two-handed version, which was a polearm. It consisted of a three-feet long wooden shaft with a long curved iron blade of nearly-equal length attached to the end. The blade was sharpened only on the inside, and was reputed to be devastatingly effective. However, it left its user vulnerable because, using a two-handed weapon, the warrior could not also make use of a shield. Alternatively, it might be used as a hook, pulling away shields and cutting at vulnerable limbs.

Using the falx, the Dacian warriors were able to counter the power of the compact, massed Roman formations. During the time of the Roman conquest of Dacia (101 - 102, 105 - 106), legionaries had reinforcing iron straps applied to their helmets. The Romans also introduced the use of leg and arm protectors (greaves and manica[citation needed]) as further protection against the falxes. This was one of the rare times in history where Roman armor was modified.

The Dacians were adept[citation needed] at surprise attacks and skillful, tactical withdrawals using the fortification system. During the wars with the Romans fought by their last king Decebalus (87-106), the Dacians almost crushed the Roman garrisons south of the Danube in a surprise[citation needed] attack launched over the frozen river (winter of 101-102). Only the intervention of Emperor Trajan with the main army saved the Romans from a major defeat. But, by 106, the Dacians were surrounded in their capital Sarmizegetusa. The city was taken after the Romans discovered and destroyed[citation needed] the capital's water supply line.

Dacians decorated their bodies with tattoos like the Illyrians[10] and the Thracians.[11] The Pannonians north of the Drava had accepted Roman rule out of fear of the Dacians.[12]

Dacia remained a Roman province until 271.

Dacians that could afford armor wore customised Phrygian type helmets with solid crests (intricately decorated), domed helmets and Sarmatian helmets.[13] They fought with spears, javelins, falces, and one-sided battle axes, and used "Draco" carnyxes as standards. Most used only shields as a form of defense. Cavalry would be armed with a spear, a long La Tène sword and an oval shield; few in number, they relied heavily on Sarmatian allies for their mounted arm.

Most[citation needed] of the infantry would wield a falx and perhaps a sica and would wear no armor at all, even shunning shields.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Mercenaries

Dacian mercenaries were uncommon in contrast to the Thracians and the Illyrians but they could be found in the service of the Greek Diadochi[14] and of the Romans.[15]

Nobility

A 2nd century chieftain would wear a bronze Phrygian type helmet, a corselet of iron scale armour, an oval wooden shield with motifs and wield a sword.[16]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Navy

The ancient historian Ptolemy mentions a naval battle between the Geto-Dacians and the Romans near the island of Eukon (most likely today's Popina Island).

Fortifications

Dacians had built fortresses all around Dacia with most of them being on the Danube.[17] A scene from Trajan's column shows Romans attacking a Dacian fortification using the "testudo".[18]

The Dacians constructed stone strongholds, davas, in the Carpathian Mountains in order to protect their capital Sarmizegetusa. The fortifications were built on a system of circular belts. This allowed[citation needed] the defenders, after a stronghold was lost, to retreat to the next one using hidden escape gates. Advanced defensive systems adopted from the Greeks made their already powerful strongholds extremely difficult obstacles.[6]

External influences

Summarize

Perspective

Scythian and Sarmatian

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

The Dacian Draco was the standard of the ancient Dacian military. It served as a standard for the Dacians of the La Tène period and its origin must clearly be sought in the art of Asia Minor sometime during the second millennium BC.[19]

Sarmatians were part[20] of the Dacian army as allies. The Roxolani became part of the Dacians while the Iazyges fought against them trying to claim their own land.[21]

The Celts played a very active role in Dacia as enemies that were easily defeated by Dacians.[22] The Scordisci were among the defeated Celts that the Dacians conquered.[23]

Greek/Hellenic

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Cothelas had become a vassal to ancient Macedon.[citation needed] Some Kings of the Getae had been Hellenized[24] The Dacians traded with the Hellenistic world based upon their mineral reserves and gained better technological and cultural strategies than their Germanic and Celtic neighbours. Advanced defensive systems made their already powerful strongholds extremely difficult obstacles.[6]

Roman

After their defeat, the Dacians were ethnically cleansed. Young men were either killed or became slaves or legionaries. The remaining population was expelled and their lands were given to colonists.[8] Later, the Romans under Domitian started minting a coin called Dacicus.[25]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

Barbarians

Dacians were spoken of by Trajan as dignified barbarians[26] consequently still dangerous, but unable to win against the might of Rome. 1st century BC poet Horace writes of them in one of his works and mentions them along with the Scythians[27] as tyrants and fierce barbarians. Later historian Tacitus writes that they are a people that can never be trusted.[28]

The Ancient Greeks[29] expressed admiration and respect for Burebista.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

List of Dacian battles

This is a list of battles or conflicts that Dacians had a leading or crucial role in, rarely as mercenaries. They were involved in massive battles against Roman legions.

- Unknown date. Celtic Boii in Bohemia against Dacian tribes from the lower Danube,[30] Dacian victory

- 1st century BC Dacians against Scordisci,[citation needed] Dacian victory

- 87, First Battle of Tapae,[citation needed] Dacian victory

- 101, Second Battle of Tapae,[citation needed] Roman victory

- 102, Battle of Adamclisi,[citation needed] Roman victory

- 103, Battle of Gatae,[citation needed] Roman victory

- 106, Battle of Sarmisegetusa,[citation needed] Roman victory

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.