Chinatown (1974 film)

Film directed by Roman Polański From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chinatown is a 1974 American neo-noir mystery film directed by Roman Polanski from a screenplay by Robert Towne. It stars Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway in the principal roles, with supporting performances by John Huston, John Hillerman, Perry Lopez, Burt Young, and Diane Ladd. The film's story is inspired by the California water wars: a series of disputes over southern California water at the beginning of the 20th century that resulted in Los Angeles securing water rights in the Owens Valley.[4] The Robert Evans production, released by Paramount Pictures, was Polanski's last film in the United States and features many elements of film noir, particularly a multi-layered story that is part mystery and part psychological drama.[5]

| Chinatown | |

|---|---|

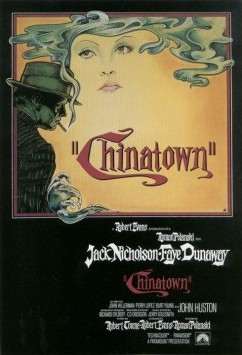

Theatrical release poster by Jim Pearsall | |

| Directed by | Roman Polanski |

| Written by | Robert Towne |

| Produced by | Robert Evans |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John A. Alonzo |

| Edited by | Sam O'Steen |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 131 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[2] |

| Box office | $29.2 million[3] |

Chinatown was released in the United States on June 20, 1974, to acclaim from critics, with praise for the narrative and screenwriting, Nicholson and Dunaway's performances, cinematography, and Polanski's direction. At the 47th Academy Awards, it was nominated for 11 Oscars, with Towne winning Best Original Screenplay. The Golden Globe Awards honored it for Best Drama, Best Director, Best Actor, and Best Screenplay. The American Film Institute placed it second among the top ten mystery films in 2008. In 1991, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[6][7] It is also often cited as one of the greatest films of all time.[8][9][10]

A sequel, The Two Jakes, was released in 1990, again starring Nicholson, who also directed, with Robert Towne returning to write the screenplay. The film failed to match the acclaim of its predecessor.

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

In 1930s Los Angeles, a woman calling herself Evelyn Mulwray hires private investigator J. J. "Jake" Gittes to trail her husband Hollis, the chief engineer at the Department of Water and Power. Gittes photographs Hollis in the company of a young woman and the pictures make their way into the Post-Record, exposing their apparent affair. Gittes is then confronted by the real Evelyn Mulwray, who threatens to sue him. He concludes that the imposter was using him to discredit Hollis.

Gittes crosses paths with his former colleague, LAPD Lieutenant Lou Escobar, when Hollis's corpse is found in a reservoir. He discovers that huge quantities of water are being released from the reservoir each night, despite the fact that LA is in the midst of a drought. Water Department Security Chief Claude Mulvihill warns him off, and Gittes has his nose slashed by one of Mulvihill's henchmen.

Now working for Evelyn, Gittes investigates Hollis's death. He learns that Hollis was once the business partner of Evelyn's wealthy father, Noah Cross. Cross offers to double Gittes's fee if he finds Hollis's supposed mistress, who has disappeared. Gittes receives a call from Ida Sessions, the woman who posed as Evelyn. She refuses to say who hired her, but urges Gittes to check the Post-Record's obituary section.

Public records reveal that much of the Northwest Valley has recently changed ownership. Gittes recognizes one of the buyers' names from the obituary section; the obituary indicates that he had been dead for a week when the deal was closed. Gittes and Evelyn bluff their way into the retirement home where the buyer had lived and discover that many of the other residents are "buyers" too, although they have no knowledge of this fact. A suspicious staff member calls Mulvihill, but Gittes and Evelyn escape him and his thugs and hide at her mansion, where they sleep together. Evelyn leaves after an urgent phone call, and Gittes follows her to a house where he sees her comforting the missing girl. He accuses her of holding the girl hostage, but Evelyn claims she is her sister, Katherine.

An anonymous call draws Gittes to Ida's apartment, where he finds her body and is confronted by Escobar. Escobar reveals that Hollis had saltwater in his lungs, indicating that he did not die in the reservoir. He suspects Evelyn murdered him and tells Gittes to produce her quickly. At the Mulwray mansion, Gittes finds the servants packing up the house, and retrieves a pair of eyeglasses from the saltwater garden pond.

Gittes confronts Evelyn about Katherine, whom she now claims is her daughter. Frustrated, he repeatedly slaps Evelyn until she breaks down and reveals that Katherine is both her sister and daughter; the girl's father is Cross, who raped Evelyn when she was 15. She tells Gittes that the eyeglasses he found did not belong to Hollis.

Gittes arranges for the women to flee to Mexico and instructs Evelyn to meet him at her butler's home in Chinatown. He summons Cross to the Mulwray residence, having deduced that Cross dropped his glasses when he drowned Hollis in the pond. Cross reveals that he is behind both the water shortage and the land grab in the Northwest Valley. Once the land is his, he will obtain a contract from the city to build a reservoir there. He discredited and killed Hollis when the latter came close to uncovering the plan.

Cross has Mulvihill take the glasses from Gittes at gunpoint. Gittes is then forced to drive them to the rendezvous in Chinatown, where the police are waiting. Escobar takes Gittes into custody as Cross approaches Katherine, identifying himself as her grandfather. Desperate to escape him, Evelyn shoots Cross in the arm and drives away with Katherine, but the police open fire, killing Evelyn. Cross pulls a screaming Katherine away, while Escobar orders the traumatized Gittes released. As he is led away by his associates, one of them tells him: "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."[a]

Cast

- Jack Nicholson as J. J. "Jake" Gittes

- Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Cross-Mulwray

- John Huston as Noah Cross

- Perry Lopez as Lieutenant Lou Escobar

- John Hillerman as Russ Yelburton

- Burt Young as Curly

- Darrell Zwerling as Hollis I. Mulwray

- Diane Ladd as Ida Sessions

- Roy Jenson as Claude Mulvihill

- Roman Polanski as Man with Knife

- Dick Bakalyan as Detective Loach

- Joe Mantell as Lawrence Walsh

- Bruce Glover as Duffy

- Nandu Hinds as Sophie

- James O'Reare as Lawyer

- James Hong as Kahn

- Beulah Quo as Maid

- Jerry Fujikawa as Gardener

- Belinda Palmer as Katherine Cross

- Roy Roberts as Mayor Bagby

- Noble Willingham as City Councilman

- Rance Howard as Irate Farmer

- Elizabeth Harding as Curly's Wife

Production

Summarize

Perspective

Background

In 1971, producer Robert Evans offered Towne $175,000 to write a screenplay for The Great Gatsby (1974), but Towne felt he could not better the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. Instead, Towne asked Evans for $25,000 to write his own story, Chinatown, to which Evans agreed.[12][13][14] Towne had originally hoped to also direct Chinatown, but realized that by taking Evans' money, he would lose control of the project's future and his role as a director.[15]

Chinatown is set in 1937 and portrays the manipulation of a critical municipal resource—water—by a cadre of shadowy oligarchs. It was the first part of Towne's planned trilogy about the character J. J. Gittes, the foibles of the Los Angeles power structure, and the subjugation of public good by private greed.[16] The second part, The Two Jakes, has Gittes caught up in another grab for a natural resource—oil—in the 1940s. It was directed by Jack Nicholson and released in 1990, but the second film's commercial and critical failure scuttled plans to make Gittes vs. Gittes,[17] about the third finite resource—land—in Los Angeles, circa 1968.[16]

Origins

The character of Hollis Mulwray was inspired by and loosely based on Irish immigrant William Mulholland (1855–1935) according to Mulholland's granddaughter.[18][19][20] Mulholland was the superintendent and chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, who oversaw the construction of the 230-mile (370-km) aqueduct that carries water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles.[19] Mulholland was considered by many to be the man who made Los Angeles possible by building the Los Angeles Aqueduct in the early 1900s.[21] The 233 mile long feat of engineering brought the water necessary for urban expansion from the Owens Valley to a Los Angeles whose growth was constrained by the limits of the Los Angeles River.[22] Mulholland credits Fred Eaton, then mayor of Los Angeles, with the idea to secure water for the city from the Owens Valley.[23]

Although the character of Hollis Mulwray was relatively minor in the film and he was killed in the early part of the movie, the events of Mulholland's life were portrayed through both the character of Mulwray and other figures in the movie. This portrayal, along with other changes to actual events that inspired Chinatown, such as the time frame which was some thirty years earlier than that of the movie, were some of the liberties with facts of Mulholland's life that the movie takes.[24]

Author Vincent Brook considers real-life Mulholland to be split, in the film, into "noble Water and Power chief Hollis Mulwray" and "mobster muscle Claude Mulvihill",[20] just as Land syndicate and Combination members, who "exploited their insider knowledge" on account of "personal greed", are "condensed into the singular, and singularly monstrous, Noah Cross".[20]

In the film, Mulwray opposes the dam wanted by Noah Cross and the city of Los Angeles, for reasons of engineering and safety, arguing he would not repeat his previous mistake, when his dam broke resulting in hundreds of deaths. This alludes to the St. Francis Dam disaster of March 12, 1928.[25] Unlike the character of Mulwray, who was concerned about the dam in Chinatown, Mulholland's role in the disaster diverged from the events in the film. Mulholland had inspected the St. Francis Dam after the dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger requested that Mulholland personally inspect the dam after Harnischfeger became concerned about the safety of the dam upon discovering cracks and brown water leaking from the base of the dam, which indicated to him the erosion of the dam's foundation.[26] Mulholland inspected the dam at around 10:30 in the morning, declaring that all was well with the structure.[26] Just before midnight that same evening, a massive failure of the dam occurred.[26] The dam's failure inundated the Santa Clara River Valley, including the town of Santa Paula, with flood water, causing the deaths of at least 431 people. The event effectively ended Mulholland's career.[27][28]

The plot of Chinatown is also drawn not just from the diversion of water from the Owens Valley via the aqueduct but also from another actual event. In the movie, water is being purposely released in order to drive the land owners out and create support for a dam through an artificial drought. The event that the movie refers to occurred in late 1903 and 1904 when underground water levels plummeted and water usage rose precipitously.[29] Rather than a deliberate release, Mulholland was able to figure out that because of faulty valves and gates in the water system, large quantities of water were being released in the overflow sewer system and then into the ocean.[29] Mulholland was able to stop the leaks.[30]

Script

According to Robert Towne, both Carey McWilliams's Southern California Country: An Island on the Land (1946) and a West magazine article called "Raymond Chandler's L.A." inspired his original screenplay.[31] In a letter to McWilliams, Towne wrote that Southern California Country "really changed my life. It taught me to look at the place where I was born, and convinced me to write about it".[32]

Towne wrote the screenplay with Jack Nicholson in mind.[12] He took the title (and the exchange "What did you do in Chinatown?" / "As little as possible") from a Hungarian vice cop, who had worked in Los Angeles's Chinatown, dealing with its confusion of dialects and gangs. The vice cop thought that "police were better off in Chinatown doing nothing, because you could never tell what went on there" and whether what a cop did helped or furthered the exploitation of victims.[12][33][34]

Polanski first learned of the script through Nicholson, as they had been searching for a suitable joint project, and the producer Robert Evans was excited at the thought that Polanski's direction would create a darker, more cynical, and European vision of the United States. Polanski was initially reluctant to return to Los Angeles (it was only a few years since the murder of his pregnant wife Sharon Tate), but was persuaded on the strength of the script.[12]

Towne wanted Cross to die and Evelyn Mulwray to survive, but the screenwriter and director argued over it, with Polanski insisting on a tragic end: "I knew that if Chinatown was to be special, not just another thriller where the good guys triumph in the final reel, Evelyn had to die".[35] They parted ways over this dispute and Polanski wrote the final scene a few days before it was shot.[12]

The original script was more than 180 pages and included a narration by Gittes; Polanski cut and reordered the story so the audience and Gittes unraveled the mysteries at the same time.

Characters and casting

- J. J. Gittes was named after Nicholson's friend, producer Harry Gittes.

- Evelyn Mulwray is, according to Towne, intended to initially seem the classic "black widow" character typical of lead female characters in film noir, but is eventually revealed to be a tragic victim. Jane Fonda was strongly considered for the role, but Polanski insisted on Dunaway.[12]

- Noah Cross: Towne said that Huston was, after Nicholson, the second-best-cast actor in the film and that he made the Cross character menacing, through his courtly performance.[12]

- Polanski appears in a cameo as the gangster who cuts Gittes' nose. The effect was accomplished with a special knife which could have actually cut Nicholson's nose if Polanski had not held it correctly.

- In 1974, after making Chinatown and while filming The Fortune, Nicholson was informed by Time magazine researchers that his "sister" was actually his mother, similarly to the revelation made in the film regarding Evelyn and Katherine.[36]

Filming

Principal photography took place from October 1973 to January 1974.[37] William A. Fraker accepted the cinematographer position from Polanski when Paramount agreed. He had worked with the studio previously on Polanski's Rosemary's Baby. Robert Evans, never consulted about the decision, insisted that the offer be rescinded since he felt pairing Polanski and Fraker again would create a team with too much control over the project and complicate the production.[38]

Between Fraker and the eventual choice John A. Alonzo, the two compromised on Stanley Cortez, but Polanski grew frustrated with Cortez's slow process, old fashioned compositional sensibility, and unfamiliarity with the Panavision equipment. Alonzo had worked on documentaries and shot film for National Geographic and for Jacques Cousteau.[39] Alonzo was chosen for his fleetness and skill with natural light a few weeks into production. Alonzo understood that Polanski wanted realism in his lighting; "He wants the soft red tile to look soft red."[40] Ultimately, only a handful of scenes in the finished film, including the orange grove confrontation, were shot by Cortez.[5] Because Polanski's English was poor, Alonzo and Polanski would communicate in Italian, which Alonzo would then translate for the crew.[41] Polanski was rigorous in his framing and use of Alonzo's vision, making the actors strictly adhere to blocking to accommodate the camera and lighting.[42]

In keeping with a technique Polanski attributes to Raymond Chandler, all of the events of the film are seen subjectively through the main character's eyes; for example, when Gittes is knocked unconscious, the film fades to black and fades in when he awakens. Gittes appears in every scene of the film.[12] This subjectivity is the same construction used in Francis Coppola's The Conversation in which the main character, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), appears in every scene in the film. The Conversation began shooting eleven months prior to Chinatown.

Soundtrack

| Chinatown | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | 1974 |

| Genre | Jazz, soundtrack |

| Label | Varèse Sarabande |

Jerry Goldsmith composed and recorded the film's score in ten days, after producer Robert Evans rejected Phillip Lambro's original effort at the last minute. It received an Academy Award nomination and remains widely praised,[43][44][45] ranking ninth on the American Film Institute's list of the top 25 American film scores.[46] Goldsmith's score, with "haunting" trumpet solos by Hollywood studio musician and MGM's first trumpet Uan Rasey, was released through ABC Records and features 12 tracks at a running time just over 30 minutes. It was later reissued on CD by the Varèse Sarabande label. Rasey related that Goldsmith "told [him] to play it sexy — but like it's not good sex!"[44]

- "Love Theme from Chinatown (Main Title)"

- "Noah Cross"

- "Easy Living" (Rainger, Robin)

- "Jake and Evelyn"

- "I Can't Get Started" (Duke, Gershwin)

- "The Last of Ida"

- "The Captive"

- "The Boy on a Horse"

- "The Way You Look Tonight" (Kern, Fields)

- "The Wrong Clue"

- "J. J. Gittes"

- "Love Theme from Chinatown (End Title)"

Historical background

Summarize

Perspective

In his 2004 film essay and documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself, film scholar Thom Andersen lays out the complex relationship between Chinatown's script and its historical background:

Chinatown isn't a docudrama, it's a fiction. The water project it depicts isn't the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, engineered by William Mulholland before the First World War. Chinatown is set in 1937, not 1905. The Mulholland-like figure—"Hollis Mulwray"—isn't the chief architect of the project, but rather its strongest opponent, who must be discredited and murdered. Mulwray is against the "Alto Vallejo Dam" because it's unsafe, not because it's stealing water from somebody else... But there are echoes of Mulholland's aqueduct project in Chinatown... Mulholland's project enriched its promoters through insider land deals in the San Fernando Valley, just like the dam project in Chinatown. The disgruntled San Fernando Valley farmers of Chinatown, forced to sell off their land at bargain prices because of an artificial drought, seem like stand-ins for the Owens Valley settlers whose homesteads turned to dust when Los Angeles took the water that irrigated them. The "Van Der Lip Dam" disaster, which Hollis Mulwray cites to explain his opposition to the proposed dam, is an obvious reference to the collapse of the Saint Francis Dam in 1928. Mulholland built this dam after completing the aqueduct and its failure was the greatest man-made disaster in the history of California. These echoes have led many viewers to regard Chinatown, not only as docudrama, but as truth—the real secret history of how Los Angeles got its water. And it has become a ruling metaphor of the non-fictional critiques of Los Angeles development.[47]

Analysis and interpretation

Summarize

Perspective

In a 1975 issue of Film Quarterly, Wayne D. McGinnis compared Chinatown to Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. He suggested that a "wasteland motif predominates in both works", in which a character (Noah Cross in Chinatown and Oedipus in Oedipus Rex) uses "a plague on a city" to get into public power and then harbor corruption. McGinnis wrote that both works allude to "a sterility of moral values in its own era": of Athens in "a time of intellectual upheaval [...] after the heroic battle of Marathon" in Oedipus Rex and of America in the Watergate era in Chinatown. He also argued that in the film, director Roman Polanski splits Sophocles' Oedipus into two morally polar figures, with the film's protagonist Detective Jake Gittes paralleling the "good" Oedipus: the one uncovering the source of corruption. McGinnis asserted that after "confronting the web of evil perpetrated by Cross [...] Gittes is the Oedipus whose success, to the use the words of Cleanth Brooks and Robert B. Heilman, 'has tended to blind [him] to possibilities which pure reason fails to see'". McGinnis concluded that "There is finally pity for the doomed, ignorant Gittes, just as there is pity for the blind Oedipus in Sophocles", however, "Gittes' real sight, like Oedipus, comes too late".[7]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Box office

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2018) |

The film earned $29 million or the equivalent of approximately $185.5 million in 2025 dollars at the North American box office.[3]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, Chinatown holds an approval rating of 98% based on 147 reviews, with an average rating of 9.40/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "As bruised and cynical as the decade that produced it, this noir classic benefits from Robert Towne's brilliant screenplay, director Roman Polanski's steady hand, and wonderful performances from Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway".[48] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 23 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[49] Roger Ebert added it to his "Great Movies" list, saying that Nicholson's performance was "key in keeping Chinatown from becoming just a genre crime picture", along with Towne's screenplay, concluding that the film "seems to settle easily beside the original noirs".[50]

Although the film was widely acclaimed by prominent critics upon its release, Vincent Canby of The New York Times was not impressed with the screenplay as compared to the film's predecessors, saying, "Mr. Polanski and Mr. Towne have attempted nothing so witty and entertaining, being content instead to make a competently stylish, more or less thirties-ish movie that continually made me wish I were back seeing The Maltese Falcon or The Big Sleep", but noted Nicholson's performance, calling it the film's "major contribution to the genre".[51]

Accolades

Summarize

Perspective

Other honors

- 2010 – Best film of all time, The Guardian[8]

- 2012 – In the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight & Sound polls of the greatest films ever made, Chinatown was 78th among critics and 91st among directors.

- 2015 – The film ranked 12th on BBC's "100 Greatest American Films" list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[66]

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Ranked 19th

- 2001 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Ranked 16th

- 2003 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Noah Cross – Ranked 16th Villain

- J.J. Gittes – Nominated Hero

- 2005 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Forget it, Jake, it's Chinatown" – Ranked 74th

- 2005 – AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Ranked 9th

- 2007 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Ranked 21st

- 2008 – AFI's 10 Top 10 mystery film – Ranked 2nd

Subsequent works

A sequel film, The Two Jakes, was released in 1990, again starring Nicholson, who also directed, with Robert Towne returning to write the screenplay. It was not met with the same financial or critical success as the first film.

A prequel television series by David Fincher and Towne for Netflix about Gittes starting his agency was reported to be in the works in November 2019.[67]

A film about the making of Chinatown, based on the non-fiction book The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, was reported in August 2020 to be in the works, with Ben Affleck as director and writer.[68]

Legacy

Towne's screenplay has become legendary among critics and filmmakers, often cited as one of the best examples of the craft,[16][69][70] though Polanski decided on the fatal final scene. While it has been reported that Towne envisioned a happy ending, he has denied these claims and said simply that he initially found Polanski's ending to be excessively melodramatic. He explained in a 1997 interview: "The way I had seen it was that Evelyn would kill her father but end up in jail for it, unable to give the real reason why it happened. And the detective [Jack Nicholson] couldn't talk about it either, so it was bleak in its own way". Towne retrospectively concluded that "Roman was right",[71] later arguing that Polanski's stark and simple ending, due to the complexity of the events preceding it, was more fitting than his own, which he described as equally bleak but "too complicated and too literary".[72]

Chinatown brought more public awareness to the land dealings and disputes over water rights, which arose while drawing Los Angeles' water supply from the Owens Valley in the 1910s.[73]

See also

Notes

- The film title and the oft-quoted line "Forget it, Jake, it's Chinatown," almost certainly refer to "Old Chinatown", or at least the popular perception thereof.[11] Old Chinatown was gradually demolished, starting in 1933, to allow for construction of Union Station, with the grand opening of "New Chinatown" in 1938.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.