Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

1872 Scotland v England football match

First international football match From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

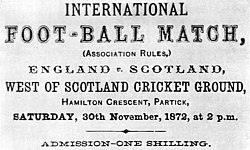

The 1872 association football match between the national teams of Scotland and England is officially recognised by FIFA as the first international. It took place on 30 November 1872 at Hamilton Crescent, the West of Scotland Cricket Club's ground in Partick, Glasgow. The match was watched by 4,000 spectators and finished as a 0–0 draw.[1]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Following public challenges issued in Glasgow and Edinburgh newspapers by The Football Association (FA) secretary Charles Alcock, the first encounter of five matches between teams representing England and Scotland took place in London on 5 March 1870 at The Oval, resulting in a 1–1 draw.[1] The second match was played on 19 November 1870, England 1–0 Scotland. This was followed by matches on 25 February 1871, England 1–1 Scotland; 18 November 1871, England 2–1 Scotland; and 24 February 1872, England 1–0 Scotland.[2] Most players selected for the Scottish side in these early "internationals" were from the London area, although players based in Scotland were also invited. The only player affiliated to a Scottish club was Robert Smith of Queen's Park, Glasgow, who played in the November 1870 match and both of the 1871 games. Robert Smith and James Smith (both of the Queen's Park club) were listed publicly for the February 1872 game, but neither played in the match.[3]

After the 1870 matches, there was resentment in Scotland that their team did not contain more players based in Scotland. Alcock himself was categorical about where he felt responsibility lay, writing in The Scotsman newspaper:

I must join issue with your correspondent in some instances. First, I assert that of whatever the Scotch eleven may have been composed the right to play was open to every Scotchman [Alcock's italics] whether his lines were cast North or South of the Tweed and that if in the face of the invitations publicly given through the columns of leading journals of Scotland the representative eleven consisted chiefly of Anglo-Scotians ... the fault lies on the heads of the players of the north, not on the management who sought the services of all alike impartially. To call the team London Scotchmen contributes nothing. The match was, as announced, to all intents and purposes between England and Scotland.[4]

Alcock then proceeded to offer another challenge with a Scottish team drawn from Scotland and proposed the north of England as a venue. He appeared to be particularly concerned about the number of players in Scottish football teams at the time, adding: "More than eleven we do not care to play as it is with greater numbers it is our opinion the game becomes less scientific and more a trial of charging and brute force ... Charles W Alcock, Hon Sec of Football Association and Captain of English Eleven".[4] One reason for the absence of a formal response to Alcock's challenge may have been different football codes being followed in Scotland at the time. A written reply to Alcock's letter above states: "Mr Alcock's challenge to meet a Scotch eleven on the borders sounds very well and is doubtless well meant. But it may not be generally well known that Mr Alcock is a very leading supporter of what is called the 'association game' ... devotees of the 'association' rules will find no foemen worthy of their steel in Scotland".[5] Despite this the FA were hoping to play in Scotland as early as February 1872.[6]

In 1872, Queen's Park, as Scotland's leading club, took up Alcock's challenge, despite there being no Scottish Football Association to sanction it. In the FA's minutes of 3 October 1872 it was noted "In order to further the interests of the Association in Scotland, it was decided that during the current season, a team should be sent to Glasgow to play a match v Scotland".

The match was arranged for 30 November (St Andrew's Day), and the West of Scotland Cricket Club's ground at Hamilton Crescent in Partick was selected as the venue.

Remove ads

The match

Summarize

Perspective

All eleven Scottish players were members of the Queen's Park, the leading Scottish club at this time,[1] although three players were also members of other clubs; William Ker of Granville F.C. and the Smith brothers of South Norwood F.C.[7] Scotland had hoped to obtain the services of Arthur Kinnaird of The Wanderers and Henry Renny-Tailyour of Royal Engineers but both were unavailable.[1] The teams for this match were gathered together "with some difficulty, each side losing some of their best men almost at the last moment".[8] The Scottish side was selected by goalkeeper and captain Robert Gardner.[1] The English side was selected by Charles Alcock and contained players from nine clubs; Alcock himself was unable to play due to injury.[1] The match, initially scheduled for 2pm,[1] was delayed for 20 minutes. The 4,000 spectators paid an entry fee of a shilling, the same amount charged at the 1872 FA Cup Final.[1]

The Scots wore dark blue shirts. This match is, however, not the origin of the blue Scotland shirt, as contemporary reports of the 5 February 1872 rugby international at the Oval clearly show that "the Scotch were easily distinguishable by their uniform of blue jerseys ... the jerseys having the thistle embroidered."[9] The thistle had been worn previously in the 1871 rugby international.[10] The English wore white shirts. The English wore caps, while the Scots wore red cowls.

The match itself illustrated the advantage gained by the Queen's Park players "through knowing each others' play"[11] as all came from the same club. Contemporary match reports clearly show dribbling play by both the English and the Scottish sides, for example: "The Scotch now came away with a great rush, Leckie and others dribbling the ball so smartly that the English lines were closely besieged and the ball was soon behind",[11] "Weir now had a splendid run for Scotland into the heart of his opponents' territory[11] and "Kerr ... closed the match by the most brilliant run of the day, dribbling the ball past the whole field."[8]

Illustrations of the first international at Hamilton Crescent, by William Ralston

Although the Scottish team are acknowledged to have worked better together during the first half, the contemporary account in The Scotsman newspaper acknowledges that in the second half England played similarly: "During the first half of the game the English team did not work so well together, but in the second half they left nothing to be desired in this respect."[11] There is no specific description of a passing manoeuvre in the lengthy contemporary match reports, although two weeks' later The Graphic reported "[Scotland] seem to be adepts at passing the ball".[8] There is no evidence in the article that the author attended the match, as the reader is clearly pointed to match descriptions in "sporting journals". It is also of note that the 5 March 1872 match between Wanderers and Queen's Park contains no evidence of ball passing.[12]

At half-time, both teams rotated the goalkeeping duties among their players: England from Robert Barker to William Maynard, and Scotland from Gardner to Robert Smith.[13]

On a pitch that was heavy due to the continuous rain over the previous three days, the smaller and lighter Scottish side pushed their English counterparts hard. The Scots had a goal disallowed in the first half after the umpires decided that the ball had cleared the tape that was used to represent the crossbar.[14][13] The latter part of the match saw the Scots defence under pressure by the heavier English forwards. The Scots played two full backs, two half backs and six forwards. The English played only one full back, one half back and eight forwards. Since three defenders were required for a ball played to be onside, the English system was virtually a ready-made offside trap. Scotland came closest to winning the match when, in the closing stages, a Robert Leckie shot landed on top of the tape.[1]

Though the match finished goalless, the quality of play was widely praised. "It was allowed to be the best game ever seen in Scotland" wrote the Aberdeen Journal.[citation needed] The sport magazine The Field wrote that "The result was received with rapturous applause by the spectators and the cheers proposed by each XI for their antagonists were continued by the onlookers until the last member of the two sides had disappeared" and that "The match was in every sense a signal success, as the play was throughout as spirited and a pleasant as can possibly be imagined."[15]

The reports of the match that were published in the newspapers reveal further details of the 1872 Laws of the Game.[16] Scotland won a defensive corner kick after England's attackers kicked the ball over the goal-line (a feature borrowed from Sheffield Rules but discarded in 1873).[13] The throw-in was awarded to the first team to touch the ball down after it went out of play (this too would be changed in 1873);[13] and there was a break for half-time only because no goals had been scored in the first half.[13]

Remove ads

Match details

Scotland

|

England

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Positions

- GK = Goalkeeper

- BK = Back

- HB = Half-back

- FW = Forward

See also

Notes

Robert Barker (Hertfordshire Rangers)

Harwood Greenhalgh (Notts County)

Reginald Courtenay Welch (Harrow Chequers)

Frederick Maddison (Oxford University)

William Maynard (1st Surrey Rifles)

John Brockbank (Cambridge University)

Charles Clegg (Sheffield Wednesday)

Arnold Kirke Smith (Oxford University)

Cuthbert Ottaway (Oxford University)

Charles Chenery (Crystal Palace)

Charles Morice (Barnes)

Remove ads

Sources

- Mitchell, Andy (2012). First Elevens, the birth of international football. Andy Mitchell Media. ISBN 9781475206845.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads