热门问题

时间线

聊天

视角

无政府主义经济学

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

Remove ads

无政府主义经济学是指无政府主义政治哲学在经济活动方面的理论与实践。许多无政府主义者是反权威的反资本主义者,而无政府主义本身通常被认为是自由意志社会主义(无国家社会主义)的一种形式[1][2][3]。无政府主义者通常支持从占有和使用的角度定义的、互助性质用益物权的私人财产[4][5],反对资本聚集、利息、垄断、生产资料(资本、土地和劳动资料)等生产性财产私有制、利润、租赁、高利贷和工资奴役这些常被视为资本主义固有特征的概念[6][7]。

无政府主义常被视为一种激进的左派或极左派运动[8][9],其许多经济学以及法律哲学反映了对左翼和社会主义政治的反权威、反国家和自由意志主义的解释,如无政府共产主义、集体无政府主义、自由市场无政府主义、个人无政府主义、互助主义和无政府工团主义,以及其他自由意志主义的社会主义政治经济学[10]。但大多数无政府主义理论家不认为无政府资本主义属于无政府主义,这是因为无政府主义在历史上是一反资本主义运动,被视为与资本主义不相容[2][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]。同样与无政府资本主义者不同,自由市场个人无政府主义者仍保留了劳动价值理论及社会主义政治经济学[13]。

无政府主义者认为,资本主义制度产生且促进了他们认为具有压迫性的各种经济活动形式,比如不从使用和占有方面定义的私有财产、等级制度的生产关系、收租、在交换中获取利润以及收取贷款的利息[1][3][18]。无政府主义者认为统治阶级,如资本家、地主,以及所有其他形式非自愿的、强制性的等级制度,社会经济制度和社会阶层,是社会的主要统治者。而通过工人自治、民主教育以及合作住房能够最终消灭统治阶级。与右派自由意志主义不同,无政府主义者支持占有权主义而非财产权主义[19][20][21]。

Remove ads

历史

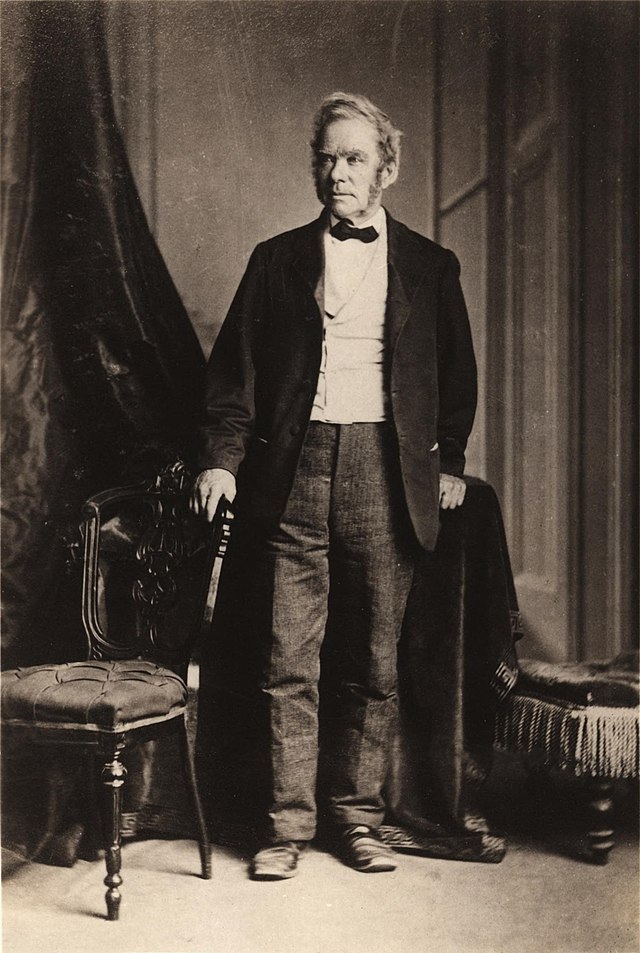

英国早期的无政府主义者威廉·戈德温对经济学的看法可以被概括为以下几点:“他设想了在各种手工业中实现专业化的可能性,这会使一个人从事他最擅长的工作,并将他的剩余产品分配给可能需要它们的人,并从他的邻居生产的剩余产品中获得他自己需要的其他东西,但这些总建立在自由分配而不是交换的基础上。显然,尽管戈德温对机械的未来进行了推测,但他的理想社会仍建立在手工业和种植业的经济基础上的”[22]。

而对于有一定影响力的德国个人无政府主义哲学家迈克斯·施蒂纳来说,“私有财产是一种‘在法律恩惠下存在’的幽灵,而它‘在法律的效力下才转变成‘我的财产’’。换言之,私有财产纯粹是依靠‘国家的保护和恩惠’才能存在。施蒂纳同时意识到了,对于一个国家的‘善良公民’来说,无论保护他们私有财产的是专制君主还是立宪君主,抑或是共和国,只要他们得到财产和律法上的保护,就对他们来说没有任何区别。而他们的原则也是‘爱’有利息的占有[……]的劳动资本、不包含自己劳动却包含他人和资本劳动的劳动,而不是‘爱’劳动这一原则”[23]。

皮埃尔-约瑟夫·蒲鲁东曾参与里昂互助派的活动,后来使用这个组织的名字来描述他自己的观点[24]。而在《什么是互助论?》中,克拉伦斯·李·斯瓦尔兹认为,“互助论一词最早应当是被英国作家约翰·格雷在1832年使用”[25]。蒲鲁东反对保护资本家、银行和土地利益的政府特权,也反对财产的积累或获得,以及导致财产积累的任何形式的胁迫,他认为这些阻碍了竞争,使财富掌握在少数人手中。

蒲鲁东赞成个人有权保留自己的劳动成果作为自己的财产,但认为任何超出个人生产和能够拥有的财产都是非法的。因此,他认为私有财产既是自由的必要条件,也是通往暴政的道路,对前者来说是劳动的结果,是劳动的需要,对后者来说则是剥削的结果(利润、利息、租金和税收)。他一般称前者为“占有”,后者为“财产”。对于大工业和大企业,他支持用工人协会取代雇佣制;他还反对土地所有权。

约书亚·沃伦被广泛认为是美国的第一个无政府主义者[26],他在1833年编辑的四页周报《和平革命者》是第一份出版的无政府主义期刊[27]。沃伦还发明了“成本价格限制”一词,这里的“成本”不是指支付的货币面值,而是指人们为生产一件物品所付出的劳动[28]。由此,“他提出了一种新的制度,在这种制度下,说明某个人做了多少个小时的工作的证书将作为货币。人们可以在当地的时间商店用这种货币换取相同工作时间的商品”[26]。

为检验其理论,沃伦建立了一个名为辛辛那提时间商店的实验性、“以工换工”的商店。该所商店前后存在了接近三年,后来被沃伦自行关停以支持他的其他几个实验性互助主义项目。沃伦曾称史蒂芬·皮尔·安德鲁斯在1852年出版的《社会的科学》一书清晰完整地阐述了他的理论[29]。

而在欧洲,早期的无政府共产主义者约瑟夫·迪亚契称自己是“自由意志主义者”,他也是第一位如此自称的人[30]。他提出与蒲鲁东不同的看法:“工人无权于他或她劳动所得的产物,但有权满足他或她的需求,无论其性质为何”[31][32][33]。回到纽约后,他得以创办《自由报》并在其上连载他的书籍。该报从1858年6月9日至1861年2月4日共出版了27期,也是在美国出版的第一份无政府共产主义期刊。

Remove ads

19世纪,支持国家社会主义的卡尔·马克思成为了第一国际及其总委员会的领导人物。而蒲鲁东及互助主义者支持政治弃权主义并保留少数个人财产[34][35]。1872年,第一国际的反权威主义派在圣伊米耶大会上宣布,“无产阶级的愿望仅仅是建立一个绝对自由的、所有人劳动且平等、绝对独立于所有的政治政府之外的经济组织和联邦”。在这一组织和联邦中,每一个工人都“享受其劳动的总产品的权利,从而能有在集体环境中充分发展其智力、物质和道德力量的手段”,而这种变革性的转变只能是“无产阶级本身、其行业机构和自治公社自发行动的结果”[36]。

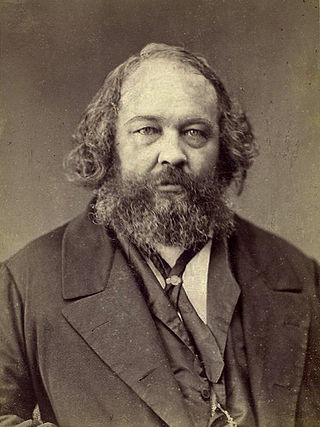

集体无政府主义者主张同时按照劳动种类和劳动量在“按劳分配”的基础上给予报酬[37]。1868年,俄国革命家米哈伊尔·亚历山德罗维奇·巴枯宁和他的集体无政府主义者同伙在和平与自由同盟失败后加入了第一国际[38]。他们与第一国际中主张以革命方式推翻国家并使财产集体化的联邦社会主义派相互支持[39]。第一国际的会员荷西普·鲁纳斯-普哈尔斯在其文章《集体主义》中曾介绍道西班牙地区工人联合会在1882年也秉持了类似集体无政府主义的立场[36]。

无政府共产主义是一套连贯的现代经济政治哲学,最早的支持者包括第一国际意大利分部的卡洛·卡菲罗、埃米利奥·科维利、埃里科·马拉泰斯塔、安德烈·科斯塔及一些前马志尼共和派[40]。出于对巴枯宁的尊重,他们直到巴枯宁去世后才明确表示他们与集体无政府主义存在分歧。集体无政府主义者认为应将生产资料的所有权集体化,同时保留与每个人的劳动量和劳动种类相称的报酬,而无政府共产主义者则进一步要求将劳动产物同样集体化[41]。虽然这两个团体都反对资本主义,但无政府共产主义者不再认同蒲鲁东和巴枯宁认为个人有权获得其个人劳动的产品这一点。埃里科·马拉泰斯塔认为:“与其冒着混淆的风险区分你和我各自所做的事情,不如让我们都工作,把一切生产所得放在一起。这样,每个人都能竭尽所能地劳动直到物质极大充裕,每个人都能尽可能地取其所需直到某一物质不再极大富裕”[42]。

到19世纪80年代初,大多数欧洲无政府主义运动都采取了无政府共产主义的立场,主张废除雇佣劳动并按需分配。具有讽刺意味的是,“集体主义”的标签后来更多地与马克思主义中的国家社会主义者联系在一起,他们主张在向全面共产主义过渡期间保留某种工资制度。无政府共产主义者彼得·阿列克谢耶维奇·克鲁泡特金在他的文章《集产主义的工钱制度》和书籍《面包与自由》中对国家社会主义者进行了抨击。卡菲罗在他1880年的著作《安那其与共产主义》中进一步解释道,劳动产品的私有化将导致资本的不平等积累,从而导致社会阶级及其对立的重新出现;进而导致国家的复活:“如果我们容许私人占有劳动产品,我们就将被迫保留货币,使财富或多或少地按照个人的功绩而非个人的需要积累”[31]。

总结

视角

在无政府主义发展迅速的西班牙,无政府共产主义和集体无政府主义之间的争论再度爆发:“两种意识形态,一种植根于乡村,另一种植根于工厂,使西班牙无政府工团主义中的自由意志共产主义在某种程度上发生了分裂:其一是更加地方、富有农村精神、更南方并植根于安达卢西亚的公社主义,其二是更城市、富有统一精神、更北方且植根于加泰罗尼亚的工团主义”[43]。

西班牙的无政府主义理论家们在这个问题上也有分歧。一派理论家对克鲁泡特金和他渊博但易懂的中世纪理想公社给予了很大的支持,他们认为这继承了西班牙原始农民社区的传统。公社主义派最喜欢的口号是“自由公社”。而另一派无政府主义理论家倾向于追随西班牙集体主义、工团主义和国际工人运动的创始人巴枯宁和他的弟子里卡多·梅拉[43],他们担忧克鲁泡特金的公社无法完成经济统一化,因此认为需要一个比较漫长的、按劳分配而非按需分配的过渡期。工团主义派设想中未来的经济结构由地方工会组织和工业部门联合会组成[43]。

1932年,西班牙无政府主义理论家艾萨克·普恩特发表了无政府共产主义的纲要,其中的观点在1936年5月被全国劳工联盟在萨拉戈萨大会上所接纳[43]。西班牙无政府主义经济学家迭戈·阿瓦德·德·桑蒂连同时发表了一篇经济学论文《革命的经济组织》[43],他在论文中反对克鲁泡特金的“自由公社”:

“最理想的公社是与国家和其他处于革命状态的国家的总体经济相联系、相联合、相融合的公社”。用九头鸟式的所有者取代单一的所有者不是集体主义更非自我管理。土地、工厂、矿山、运输工具都是所有人工作的产物,也因此必须为所有人服务。现在的经济不是地方性的,甚至也不是全国性的,而是世界性的。现代生活的特点包含一切生产和分配力的凝集。“有指导、有计划的社会化经济是当务之急,也符合现代经济在世界发展中的趋势”[43]。

桑蒂连在西班牙革命中发挥了重要作用。他随后曾任反法西斯民兵中央委员会的成员,加泰罗尼亚经济委员会的成员和加泰罗尼亚政府的经济部长[43]。无政府主义史学家乔治·伍德科克后来报告称:

几个月来,无政府主义者控制的民兵部队成了这些地区常见的武装力量。工厂大部分被工人接管并由全国劳工联盟的委员会管理;而村庄里的土地要么被分给了每一个人,要么干脆集体化,其中许多村庄还试图建立克鲁泡特金所倡导的那种自由意志主义公社。由上可以看出,集体化的开端在村庄和工厂差别不大。村庄里的原地主已经逃亡,原本的村镇民兵被杀或被赶走,村庄联合体逐步转变成了一个人民大会,每个村民都可以直接参与社区事务。人们还选出了一个行政委员会,但它在民众的持续监督下运作,且每周至少召开一次全体大会,以加速实现自由共产主义。在工厂里也发生了类似的行为,工人委员会对工人大会负责,技术人员(在少数情况下是前业主或经理)根据工人的意见规划生产[22]。

Remove ads

理论经济体系

一般而言,古典无政府主义是指19世纪的无政府主义运动与思想流派,而后古典无政府主义是指20世纪中叶及之后的无政府主义运动与思想流派。

互助论是一种无政府主义思想,其理论基础可以追溯至皮埃尔-约瑟夫·蒲鲁东:他在其著作中设想了一种新的社会。在这种新社会里,每个人以个人或集体的形式拥有一种生产资料,自由市场上的贸易以劳动为计量单位[44]。蒲鲁东还设想了一种互助信贷银行,这种银行以最低的利率向生产者提供贷款,利率仅够支付额外的管理成本[45]。互助论以劳动价值理论为基础,认为当劳动或其产品被出售时,它应该能交换到体现“生产非常相似且有同等效用的物品所需的劳动量”的商品或服务[46]。

一些互助论者认为,如果国家不因市场竞争的加剧进行干预,个人所得会与他们的劳动量相匹配[47]。互助论者反对个人通过贷款、投资和出租等方式获得收入,他们认为这些人并不是通过劳动获得收入。他们中的一些人还认为,如果国家停止干预市场,这些类型的收入将由于资本竞争的加剧而消失[48] 。

虽然蒲鲁东也反对这些收入,但他亦表示:“[……]我从来没有想过要[……]通过国家法令压制或是禁止土地及资本产生的利息。我认为,包括这些在内所有人类的活动都应该保持自由,并为所有人所选择”[49]。就工人对其劳动收入的权利而言,互助论者支持市场和劳动产物的私有制。然而,他们也主张有条件的土地所有权,即只有当土地在被使用或被占用(蒲鲁东称之为“占有”)时,其才可以被私人拥有[50]。

蒲鲁东的互助论支持工人合作社[51],因为“我们不必犹豫,因为我们别无选择[……]有必要在工人中成立一个协会[……],如果没有这个协会,他们就会一直保持上下级的阶级关系,就会出现两个[……]种姓的人,这些不利于一个自由民主的社会”,因此“工人有必要组成为所有成员提供平等便利条件的、民主的社会,否则他们就将重新回到封建制”[52]。而对于资本财(人造的、非土地性质的“生产资料”),互助论者的观点随这些物质公共性质的不同而变化。

Remove ads

互助论一词曾在历史上被多次使用。夏尔·傅立叶在1822年使用过法语词“mutualisme”[53],但傅立叶并未用这个词指代一种经济体系。1826年,美国欧文主义者在《新和谐报》中使用了“mutualist”一词[54]。1830年代,法国里昂的劳工组织自称为“Mutuellist”。皮埃尔-约瑟夫·蒲鲁东也参与了他们的活动,并在后来用这个词指代他自己的理论[24]。

在《什么是互助论》一书中,克拉伦斯·李·斯瓦尔兹认为,“互助论一词最早应当是被英国作家约翰·格雷在1832年使用”[25]。约翰·格雷的《人类幸福讲座》于1826年在美国首次出版时,出版商在书的最后附上了互利友好协会的序言和章程。

1846年,蒲鲁东在作品中提到了“互助性”一词,并在1848年的《革命者纲领》中使用了“mutuellisme”一词。1850年,威廉·葛林使用了“mutualism”一词指代与蒲鲁东主张类似的互助信贷系统。同样在1850年,美国报纸《时代精神》刊登了约书亚·金·英格尔斯[55]和阿尔伯特·布里斯班[56]二人关于建立“互助镇”的提案,以及蒲鲁东[57]、葛林、皮埃尔·勒鲁等人的一批文章。

美国无政府主义史学家尤妮斯·米内特·舒斯特称:“显然……至少早在1848年,美国就出现了蒲鲁东式的无政府主义,而且其拥护者没有意识到这种思想与约书亚·沃伦和史蒂芬·皮尔·安德鲁斯的个人无政府主义之间的关系……威廉·葛林以最纯粹、最系统的形式将蒲鲁东的互助主义展现在了大家面前”[58]。后来,本杰明·塔克在他所管理的《自由》上发文尝试将麦克斯·施蒂纳的利己主义与沃伦和蒲鲁东的经济学相融合。互助论还与两种币制改革有关:工分制最早在欧文主义者圈子中传播,并在新哈莫尼的成员与约书亚·沃伦合作后才得到了第一次实践检验;互助银行则致力于将所有形式的财富货币化并扩大自由信贷,其最常被认为与葛林有关,但葛林实际上是从蒲鲁东等人那获得了灵感。

互助论者认为,应由人民通过建立自由信贷系统产生自由银行制度。他们认为现在的银行就如资本家垄断土地一般垄断了货币。《互助主义政治经济学研究》的作者、当代互助论者凯文·卡森[59]认为,资本主义[3]建立在“与封建制度一样大规模的抢劫行为”,并认为资本主义不可能在没有国家的情况下存在[60],他还认为:“正是国家的干预使得资本主义逐渐脱离了自由市场”。罗伯特·格拉汉姆则注意到,“蒲鲁东的市场社会主义与他的产业民主和工人自我管理的概念有着不可分割的联系”[61]。K·史蒂文·文森特在他的分析中指出:“蒲鲁东一直主张将经济的控制和指导权还给工人”、“强大的工人协会[……]将使工人能够通过选举共同决定企业每天如何运作”[62]。

Remove ads

集体无政府主义是一种革命社会主义[63]学说,其主张废除国家和生产资料的私有制,实现生产者自己对生产资料的集体所有、控制和管理。关于生产资料如何集体化这一问题,集体无政府主义者最初设想是工人会集体反抗并强行将生产资料集体化[63]。之后,工人的薪水会由民主组织根据他们劳动的时间来决定。这些工资将被用来在社区市场上购买商品[64]。

这与无政府共产主义形成鲜明对比:在无政府共产主义设想的理想社会中,工资将被废除,人们通过“按需分配”的商品仓库解决需求问题。与其名字不同,集体无政府主义是一种结合了个人主义与集体主义的学说[65]。集体无政府主义也最常用于描述与巴枯宁、第一国际反权威派和早期西班牙无政府主义运动有关的理论和思想。

总结

视角

集体无政府主义者最初使用“集体主义”一词以示自身与皮埃尔-约瑟夫·蒲鲁东的互助论及卡尔·马克思的国家社会主义的差异。米哈伊尔·巴枯宁在《联邦主义、社会主义和反神主义》写道:“我们只承认自由是任何经济的和政治的组织的唯一基础,唯一合法的创造性的原则,为了自由,我们将永远对一切哪怕是有一点类似国家社会主义和共产主义的东西提出抗议”[66]。

巴枯宁和马克思之间的争论也标志着无政府主义和马克思主义之间的摩擦逐步增大。巴枯宁反对部分马克思主义者的想法,他认为并非所有革命都需要暴力。他还强烈反对马克思的“无产阶级专政”,这一概念在后来被包括马克思列宁主义在内的先锋派社会主义者用来为一个自称代表无产阶级的政党自上而下的一党统治辩护[67]。巴枯宁坚持认为,革命必须由人民直接领导,而任何“开明的精英”只能通过在“不可见、……不强加给任何人、……不具有任何官方权利和意义”的层面上施加影响[68]。巴枯宁还认为国家应该立即被废除,因为所有形式的国家最终都会导致压迫[67]。巴枯宁有时被称为第一个论述“新阶级”的理论家,“新阶级”在这里是指由知识分子和官僚组成的阶级以人民或无产阶级的名义管理国家,但实际上却只为了他们自己的利益。巴枯宁认为:“国家一直是一些特权阶级的继承品:之前曾有过牧师阶级的国家、贵族阶级的国家、资产阶级的国家。最后,当所有其他阶级都耗尽了自己的力量时,国家就成了官僚阶级的继承品,最终国家会沦落(或者如果你不满意“沦落”这个词的话,也可以换成“擢升”)到与机器同地位”[69]。巴枯宁与马克思在对于无产阶级的看法上也有不同。“双方都同意无产阶级将在革命中发挥重要作用,但对马克思来说,无产阶级是唯一的、主要的革命者,而巴枯宁则认为,农民甚至流氓无产阶级(失业者、一般的罪犯等)都有可能取代无产阶级的地位”[70]。尼古拉斯·索伯恩写道:“巴枯宁认为工人融入资本是对更主要的革命力量的破坏。对巴枯宁来说,革命的典范应当在农民中找(这种环境被认为长期具有叛乱传统,以及其目前的社会形式——农民公社,包含着共产主义的原型),应当在受过教育的失业青年、各阶层的各种边缘人、土匪、强盗、贫穷的群众以及那些逃离、被排除在外以及还未体验工作纪律的社会边缘人中找……总之,在马克思试图纳入流氓无产阶级范畴的人中找”[71]。

集体无政府主义和无政府共产主义的区别在于,集体无政府主义强调生产性、生活性和分配性财产的集体所有,而无政府共产主义则直接否定所有权的概念,主张使用或占有本不属于任何人的生产材料[19][20]。无政府共产主义者认为,用于生存、生产和分配的财产应是全社会的共同财产,而个人财产应是私人财产[21]。集体无政府主义者也同意这一点,但他们在报酬问题上有很大的分歧——一些集体无政府主义者,如米哈伊尔·巴枯宁,主张按劳分配,而包括彼得·克鲁泡特金在内的一些无政府共产主义者认为这种分配系统会再度创造出货币,也因此会导致国家的复生[72]。

无政府主义常见问答在以下方面对比了集体无政府主义和无政府共产主义:

集体主义者和共产主义者之间的主要分歧在于革命后的“货币”上。无政府共产主义者认为有必要废除货币,而集体无政府主义者则认为关键在于结束生产资料的私有制。如克鲁泡特金所注意到的一般,“[集体无政府主义]是一切生产必需品都由劳动集团和自由公社共同拥有、劳动的报偿方式通过每个自治团体独立解决的状态”[73]。因此,虽然共产主义和集体主义都通过生产者协会来组织共同生产,但它们在如何分配生产出的商品这一点上有分期。共产主义主张所有人自由消费,而集体主义更可能采用按劳分配。不过,大多数无政府集体主义者也认同,随着时间的推移、生产力的提高和社区意识的增强,金钱将会消失[74]。

Remove ads

无政府共产主义,或称共产无政府主义、自由共产主义、自由意志共产主义[75],是一种支持废除国家、市场、货币、资本主义和私有财产(但尊重个人财产)[76],拥护生产资料公有制[77][78]、由工人委员会和自发机构所构成的横向网络所统领下依照各尽所能、各取所需进行直接民主[79][80]的政治哲学及政治理论。一些形式的无政府共产主义,比如暴动无政府主义,受利己主义和激进个人主义影响颇深,并认为无政府共产主义是实现个人自由的最好社会组织形式[81][82][83]。大多数无政府共产主义者视无政府共产主义为一种调和个人与社会之间矛盾的方式[84][85][86][87]。

废除雇佣劳动是无政府主义共产主义的核心诉求。随着财富的分配以自决的需求为基础,人们可以自由地从事他们认为最充实的活动,不必再从事无法体现他们气质和才能的工作[88]。无政府共产主义者认为,没有任何有效的方法能衡量一个人对经济贡献的价值,因为所有的财富都是所有人及过去所有人共同劳作的结果[89]。

无政府共产主义者认为,强制性的国家机器执行财产权保障了基于雇佣劳动和私有财产的经济体系,并维持了因工资或财产状况差异而不可避免的、不平等的经济关系。他们进一步认为,市场和货币体系将劳动分为不同的等级,并为个人的工作分配任意的、数字上的价值,并以此调节生产、消费和分配。他们认为,货币通过限制价格和工资的摄入,限制了个人消费劳动商品的能力。

无政府共产主义者认为货币本质上是定量物而非定性物。而他们认为,生产应该是一个性质问题:每个人的消费和分配应该由每个人自己决定,而不是由其他人对劳动、商品和服务随意地指定价格。为了取代市场,大多数无政府共产主义者支持无货币的礼物经济,在这种经济中,工人生产的商品将在社区商店中被自由分配,每个人都有权获取任何他们想要或需要的东西作为他们生产商品的报酬。

礼物经济不一定涉及如工资一般的“即刻回报”,而是由个人决定与他们的劳动产品具有同等价值的任何东西作为回报(即通常所说的以物易物)。对生产和分配的限制由相关群体中的个人决定,而不是由资本主义的财产持有者、公司、投资者、银行或其他人为的市场压力决定。最重要的是,“地主”和“租户”般的抽象关系将不再存在,因为无政府共产主义者认为这种所有权是在有条件的法律胁迫下发生的,并不是因占据某一物品而自然产生的机制。

Remove ads

无政府共产主义发展自法国大革命后的激进社会主义潮流[31][90],但直到第一国际在意大利的分部成立后才成型[40]。约瑟夫·迪亚契是早期的无政府共产主义者,也是第一位称自己为“自由意志主义者”的人[30]。他提出与普鲁东不同的看法:“工人无权于他或她劳动所得的产物,但有权满足他或她的需求,无论其性质为何”[31][32]。

无政府共产主义是一套连贯的现代经济政治哲学,最早的支持者包括第一国际意大利分部的卡洛·卡菲罗、埃米利奥·科维利、埃里科·马拉泰斯塔、安德烈·科斯塔及一些前马志尼共和派[40]。出于对巴枯宁的尊重,他们直到巴枯宁去世后才明确表示他们与集体无政府主义存在分歧[41]。集体无政府主义者认为应将生产资料的所有权集体化,同时保留与每个人的劳动量和劳动种类相称的报酬,而无政府共产主义者则进一步要求将劳动产物同样集体化。

虽然这两个团体都反对资本主义,但无政府共产主义者不再认同蒲鲁东和巴枯宁认为个人有权获得其个人劳动的产品这一点。埃里科·马拉泰斯塔认为:“与其冒着混淆的风险区分你和我各自所做的事情,不如让我们都工作,把一切生产所得放在一起。这样,每个人都能竭尽所能地劳动直到物质极大充裕,每个人都能尽可能地取其所需直到某一物质不再极大富裕”[42]。彼得·克鲁泡特金后来的理论著作在关于无政府共产主义如何建立组织以及通过叛乱反对其他组织等方面也十分重要[91]。

1917年俄国革命中,包括内斯托尔·伊万诺维奇·马赫诺在内的一批无政府主义者曾一度建立起无政府共产主义的马赫诺运动及保卫该地区的军队乌克兰革命起义军,但随后在1921年被布尔什维克击垮。作为乌克兰革命起义军的指挥官,马赫诺随后领导了一场同时反对红军和白军的游击战。他领导的革命自治运动致力于建设一个抵制国家权力的无政府主义社会——无论是这一权力来源于资本主义还是布尔什维克[92][93]。

墨西哥革命中,无政府共产主义者里卡多·弗洛雷斯·马贡领导新成立的墨西哥自由党于1910年代初发动了一系列军事攻势,最终占领了下加利福尼亚州的一些城镇[94]。克鲁泡特金所著的《面包与自由》被马贡视为无政府主义的《圣经》,也是随后1911年的马贡起义中短暂存在的革命公社的理论基础[94]。

迄今为止,知名的无政府共产主义社会的例子包括西班牙革命期间的无政府主义地区[95]和俄国革命期间的马赫诺运动。西班牙无政府主义者在1936年开始的西班牙内战中的努力使得无政府共产主义在阿拉贡、莱万特和安达卢西亚的部分地区传播开来,并在加泰罗尼亚建立了无政府主义加泰罗尼亚,然后被赢得内战的国民军政权及其盟友希特勒和墨索里尼发动的攻势、苏联支持的西班牙共产党的镇压以及来自资本主义国家和西班牙第二共和国本身的经济和军备封锁粉碎[96]。

天主教无政府主义者多萝西·戴伊支持无政府分配主义,这种思想反对从重商主义到君权结构权力集中化,是一种公民和平主义,并寻求在联合公社的模式下建立社会,在民众之间普及私有制度。一些人将这种意识形态比作互助主义,但后者一般反对私有制度,支持劳动价值理论。

参与型经济是一个由理论家、活动家麦可·阿尔伯特及罗宾·哈内尔提出的经济学模型。在阿尔伯特看来,“参与型经济和参与式社会提供了一个值得的、可行的、甚至是必要的、潜在的充分的无政府主义革命愿景”[97]。参与型经济把参与决策作为一种指导特定社会的生产、消费和资源分配的经济机制。作为当代资本主义市场经济的替代方案,以及中央计划经济社会主义的替代方案,它被描述为“无政府主义的经济愿景”[98],也因为主张生产资料由工人拥有而被视为社会主义的一种形式。

参与型经济试图建立一个公平、团结、多样性、工人自治且具备生产效率(这里的具备生产效率是指在尽可能不浪费有价值的资产的情况下完成目标)的社会。这一理论认为应主要通过以下原则和制度来实现这些目标:

阿尔伯特和哈内尔强调参与型经济仅仅是一种另类经济模型,必须要辅以同样重要的政治、文化和亲属背景才可能正常运转。两人还在著作中讨论了政治领域中的无政府主义,文化领域的文化聚合主义,家庭关系中的女性主义及性别关系可能都会是参与型社会的基础。受二人启发,史蒂芬·萨尼奥尔姆出版了一些关于探讨“参与型政治”的著作。

自由市场无政府主义是一种以互助论和个人无政府主义的经济理论为基础的思想,也是这两种自由市场无政府主义理论的复兴。自由市场无政府主义包括多种不同的个人无政府主义者、反资本主义者、左翼自由意志主义者和自由意志社会主义者提出的经济理论,比如埃米尔·阿尔芒、托马斯·霍奇斯金、米格尔·希门尼斯·伊瓜拉达、皮埃尔-约瑟夫·蒲鲁东、史蒂芬·皮尔·安德鲁斯、威廉·葛林、莱桑德·斯波纳、本杰明·塔克、约书亚·沃伦、凯文·卡森[99][100][101]、加里·沙蒂尔[102][103]、塞缪尔·爱德华·康金三世[104][105]和克里斯·马修·夏巴拉[106]等人的理论[107][108][109][110]。

无政府资本主义者主张取消公共部门,以自由放任的经济系统取而代之[111][112],该种思潮与大卫·弗里德曼[113]和穆瑞·罗斯巴德等人有关[114]。在无政府资本主义社会中,警队、法院及其他各类社会安保服务都将通过市场而非政府的税收维持。货币将会被私有化,不同的货币也会同时在市场上竞争。无政府资本主义同时汲取了奥地利学派、法律经济学和公共选择理论三方面的理论[115]。

无政府主义经济体的例子

参见

参考文献

扩展阅读

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads