热门问题

时间线

聊天

视角

可萨人

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

Remove ads

可萨人,也译作卡扎人、哈扎尔人(土耳其语:Hazarlar;阿塞拜疆语:Xəzərlər;巴什基尔语:Хазарҙар;鞑靼语:Хәзәрләр,罗马化:Xäzärlär;波斯语:خزر;乌克兰语:Хоза́ри,罗马化:Khozáry;俄语:Хаза́ры;匈牙利语:Kazárok;希腊语:Χάζαροι,罗马化:Házaroi;拉丁语:Gazari[6][注 2]/Gasani[注 3][7])是一个半游牧的突厥语民族,他们在公元6世纪末建立了一个突厥语部落联邦,形成了覆盖今天俄罗斯欧洲部分南部的一个大型商贸帝国[8]。

Remove ads

名称

他们的可汗名号是答剌罕。“可萨”一词在德文有“异教徒”,希腊文有“匈奴骑兵”,在俄文与希伯来文有“牧羊人”,在阿拉伯语有“小眼睛”的意思,在亚美尼亚与格鲁吉亚有“北方”的意思,在突厥语解为“游荡”,古代波斯史说可萨人好劫掠与长途奔袭,长矛是主要武器,亚洲人后来把类似于可萨人那样生活的也称为可萨人,在1480年代,格鲁吉亚还有自称可萨人的突厥语游牧民,哥萨克也源于此字。在车臣语中,“可萨”一词可解为“美丽谷地”。

可萨汗国

最早见于《隋书·北狄传》,《旧唐书·西戎传》和《新唐书·西域传下》称其为“突厥可萨部”,杜环《经行记》提到“苫国(叙利亚)有五节度,有兵马一万以上,北接可萨突厥,可萨北又有突厥”。他们与西突厥只有稀疏的关系(统治者是西突厥宗室,后来全然独立),他们在公元7世纪下半叶,在北高加索草原伏尔加河中下游建立了强大的可萨汗国(或称哈扎尔汗国、可萨利亚),这是西突厥崩溃后涌现的诸汗国中最强大的一个政权[9]。可萨汗国疆域东至今花剌子模、今西哈萨克斯坦州、西至多瑙河与今乌克兰,达吉斯坦是核心,南至乔治亚、车臣、克里米亚、小亚细亚东北,控制着从伏尔加-顿河草原延伸至东克里米亚和北高加索的广大地域[10],跨越东欧和西亚之间的主要贸易大动脉,成为丝绸之路北道上的一个比较重要的中转站,也是中世纪世界最重要的贸易帝国之一,在中国、中东和基辅罗斯之间的十字路口扮演着重要的商业角色[11][12]。

可萨汗国一度与东罗马帝国联盟共同对抗萨珊波斯帝国,随后长期成为东罗马帝国和草原游牧民族以及倭马亚王朝之间的缓冲国。东罗马帝国说服阿兰人攻击可萨人从而削弱其对克里米亚和高加索的控制,同时力求与北边崛起的基辅罗斯和解以便向他们传播基督教[13]。965到969年间,基辅罗斯大公斯维亚托斯拉夫·伊戈列维奇攻陷了可萨首都阿的尔,可萨汗国就此灭亡。

要确定可萨人的起源,需要密切研究他们的语言,但这一课题的困难之处在于,可萨人没有留下任何本土语料,而且可萨汗国是多语、多民族的。

通常认为可萨人最初的宗教是腾格里信仰,就像北高加索匈人和其他突厥族群一样[14]。可萨汗国的民族有突厥语部落、波斯人、乌戈尔人、斯拉夫人、哥德人和高加索人等等,这样的多民族人口似乎是腾格里信徒、犹太教徒、基督教徒和穆斯林等多种宗教的混合[15]。12世纪的两位西班牙犹太学者犹大·哈列维和Abraham ibn Daud认为,可萨汗国的统治阶层在8世纪皈依了拉比犹太教,但国内民众对犹太教的接受程度还无法确定[16]。

Remove ads

历史

后来形成可萨帝国的部落[注 4]并非一个单一族群联盟,而是臣服于一个核心突厥统治者的草原游牧民族集团[17]。许多突厥族群,例如乌古尔突厥(包括苏路羯、欧诺古尔人和保加尔人),他们曾是铁勒联盟的一部分,很早就受到沙比尔人的驱逐而向西迁徙(沙比尔人则早在4世纪就为了逃脱阿瓦尔人而迁至伏尔加河-里海-黑海地区),根据普利斯库斯的记载早在643年已居住在欧亚大草原的西部[18][19]。他们似乎是在匈奴游牧政权崩溃后从蒙古高原和南西伯利亚往西迁徙的。这是一个突厥人领导的部落联盟,民族组成五花八门,其中可能有伊朗人[注 5]、原始蒙古人、乌拉尔人和古西伯利亚人的氏族,他们在552年灭亡了一度统治中亚的柔然阿瓦尔人,随后西迁,索格底亚那地区的其他草原游牧民族也加入其中[21]。

这一联盟的统治集团可能来自西突厥的阿史那氏族[22],不过法国历史学家康斯坦丁·祖克尔曼对阿史那在可萨的形成过程中起的作用持怀疑态度[注 6]。另外一些历史学家则注意到中国和阿拉伯的史料记录几乎一样,说明阿史那与可萨之间有很强的联系,并猜想联盟首领是于651年失势或被杀的乙毗射匮可汗[23];西迁途中,这一联盟到达了阿卡齐尔的地盘[注 7],阿卡齐尔曾与东罗马共同对抗阿提拉。

Remove ads

630年后稍晚,可萨政权开始有了雏形[24][25],它是从西突厥汗国分裂而来的。西突厥军队在549年驱逐了伏尔加河流域的阿瓦尔人,使得阿瓦尔人被迫迁至今匈牙利的潘诺尼亚平原。据欧洲历史学家相信,到了568年,西突厥已在谋求与东罗马的合作来攻击波斯。佗钵可汗死后,更早的东突厥与稍晚的西突厥之间爆发了内战,佗钵可汗指定的继承人是阿波可汗,而另一个争权者则是沙钵略可汗,即阿史那摄图。

到了7世纪的第一个十年,阿史那的统叶护成功稳定了西突厥,并为拜占庭提供了关键的军事协助[26][27],但他死后西突厥在唐朝的军事打击下进一步解体成两个互相竞争的联盟,每个联盟由五个部落组成,统称“十姓”或“十箭”。与此同时,西边有两个新游牧政权兴起,即咄陆氏族统治的保加尔人旧大保加利亚和弩失毕联盟(五个部落组成,故称五弩失毕)[注 8]。咄陆在库班河-亚速海地区挑战阿瓦尔人,同时可萨人则向西巩固。657年,苏定方将军对西突厥部落取得了重大胜利,唐朝取得对东突厥的宗主权,成为东突厥游牧政权的宗主国,而保加尔和可萨这两个部落政权为争取西部草原而战。可萨占了上风,保加尔人要么屈服于可萨统治,要么在阿斯巴鲁赫的领导下,向西迁徙,穿过多瑙河,为巴尔干半岛的保加利亚第一帝国奠定了基础(679年左右)[28][29]。

可萨政权因此脱离于这个受到唐朝打击而四分五裂的北亚游牧帝国的边界之外[23],为了更多的生存空间,开始自发向西、向北扩张。东北方向达到了伏尔加河下游、向西则征服了多瑙河和第聂伯河之间的地区,并使欧诺古尔-保加尔联盟臣服之后,在670年左右,可萨汗国就这样崛起了[30],成为西突厥解体后最西边的突厥游牧政权。乌克兰裔美国学者奥梅利安·普里察克认为,欧诺古尔-保加尔联盟的语言将成为可萨汗国的通用语[31],可萨随之发展为苏联学者列夫·古米廖夫所说的“草原亚特兰蒂斯”(Степная Атлантида)[32]。欧洲历史学家将可萨汗国强盛的时期称为可萨和平,因为可萨成为了一个重要的国家贸易枢纽,使得亚欧大陆西部的商人能安全地在此地区行走和从商[33]。三百年后的公元1100年左右,一部名为波斯法尔斯的历史典籍提到萨珊帝国的沙阿库斯老一世为自己放置了三个宝座,一个代表中国,第二个代表拜占庭,第三个代表可萨。尽管这种后世的历史描写可能出自附会,因为可萨政权并不存在于这一时期,但这一传说将可萨置于与两个超级大国同等地位上,体现了可萨政权作为一个区域政权所留下的良好声誉[34][35]。

Remove ads

东罗马帝国对草原民族的总体外交政策是怂恿他们互相争斗。佩切涅格人在9世纪为拜占庭提供了大量协助以换取定期的贡品[36]。拜占庭也与古突厥结盟来对抗共同的敌人:7世纪早期他们与西突厥人合作对抗萨珊帝国。拜占庭起初称可萨利亚为图尔基亚(Tourkia),到了9世纪称之为突厥人[注 9]。在626年君士坦丁堡被围困之前和之后,希拉克略派出密使,后来则是亲自前往第比利斯寻求突厥首领统叶护的帮助[注 10],并给他礼物,许诺将自己唯一的女儿优多西娅·欧皮菲尼娅公主嫁给他[38]。统叶护派出一支军队重创了波斯帝国,第三次突厥-波斯战争由此爆发[39]。拜占庭和突厥的联合军事行动打破了亚历山大门(或里海门),他们在627年洗劫了杰尔宾特,并围困了第比利斯,东罗马人此前可能已在此部署各种早期重力抛石机来破坏城墙。战役结束后,统叶护将大约40,000名士兵留在了希拉克略手中(这一说法可能有些夸大)[40]。尽管这一历史事件中的突厥人偶尔被认为是可萨人,但更有可能是古突厥人,因为可萨是在古突厥分裂之后(稍晚于630年)才出现[24][25]。一些学者认为萨珊波斯人从未从这次入侵造成的破坏中恢复过来[注 11]。

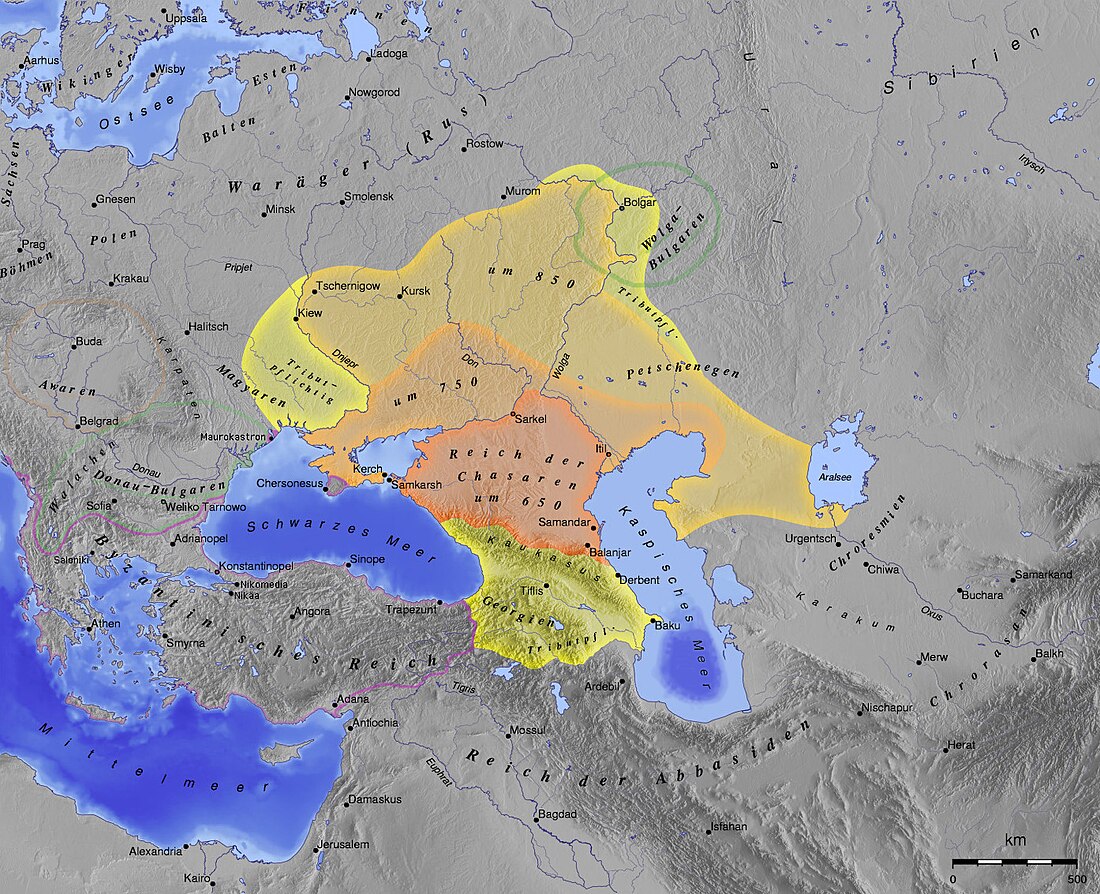

深蓝:可萨直接控制;

紫色:势力范围。

可萨成为强权之后,拜占庭人也立即开始与他们结成同盟。695年,东罗马希拉克略王朝的最后一位皇帝查士丁尼二世在被残废和罢黜后被放逐到克里米亚的克森尼索,此地由一个可萨官员(吐屯)管理。他在704或705年逃到了可萨汗国的领土,并受到可汗Busir的庇护,后者将妹妹嫁给了他,试图重获王位的查士丁尼可能认为这桩联姻将让他获得强大的可萨汗国的支持[41]。查士丁尼的妻子随即将她的名字改为西奥多拉[42]。拜占庭的篡权者提比略三世贿赂了可汗,让可汗杀死查士丁尼。受到西奥多拉的警告后,查士丁尼顺利逃脱,途中还杀死了两个可萨官员。他逃到了保加利亚,保加利亚汗帮助他重获王位。随后,尽管Busir此前背叛了他,但东罗马和可萨的联盟并没有破裂,西奥多拉也被加冕为皇后[43][44]。

数十年之后,利奥三世(717–741在位)和可萨达成了一个类似的同盟以对抗共同的敌人穆斯林阿拉伯人。他派出密使前往可萨,让儿子——后来的皇帝君士坦丁五世(741–775在位)与可汗的女儿奇奇格结婚,可汗的女儿皈依了基督教,并改名为艾琳。君士坦丁和艾琳育有一子,即后来的利奥四世,他也由此得名“哈扎尔人利奥”[45][46]。到了8世纪,可萨人控制了克里米亚,甚至将其影响扩张至东罗马属地克森尼索半岛,直到10世纪才撤回[47]。可萨和费尔干纳的雇佣兵成为了一部分拜占庭皇家禁卫军,这一职位可以通过支付7镑黄金而购得[48][49]。

Remove ads

在7世纪和8世纪,可萨人与倭马亚王朝及其继承者阿拔斯王朝进行了一系列战争。第一次阿拉伯-可萨战争始于伊斯兰教扩张的第一阶段。640年穆斯林部队已经到达亚美尼亚。642年,他们在Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah的领导下对高加索地区进行了首次突袭。652年,阿拉伯军队进攻可萨汗国首都巴伦加尔,但被击败且损失惨重;根据塔巴里等波斯历史学家的说法,战斗中双方都使用投石机对付敌方部队。许多俄罗斯史料称这一时期的可萨汗国的可汗名为埃尔比斯(Irbis),并将其描述为古突厥王室阿史那的继承人。埃尔比斯是否曾存在,以及他是否就是许多同名的古突厥统治者之一,这些问题尚不明确。

由于第一次伊斯兰内战的爆发,阿拉伯人避免再次攻击可萨人,直到8世纪初[50]。可萨人对穆斯林统治下的高加索诸公国进行了几次袭击,包括伊斯兰教第二次内战期间于683-685年进行的大规模进攻,由此获得了很多战利品和俘虏[51]。从塔巴里的记载中可以看出,可萨人与河中地区的古突厥残余势力形成了统一战线。

740年左右的高加索

第二次阿拉伯-可萨战争始于8世纪初期,高加索地区发生一系列袭击。倭马亚阿拉伯人镇压了一场大规模叛乱后在705年加强了对亚美尼亚的控制。在713或714年,倭马亚将军Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik征服了杰尔宾特,并进一步深入可萨汗国的领土。可萨人袭击了高加索阿尔巴尼亚和伊朗阿塞拜疆,但被Hasan ibn al-Nu'man领导的阿拉伯人赶回[52]。军事冲突在722年升级,3万名可萨人入侵亚美尼亚,重创当地军队。哈里发耶齐德二世向北派遣了25,000名阿拉伯援军,迅速将可萨人赶出高加索地区,恢复了杰尔宾特,并向巴兰加尔前进。巴兰加尔战役中,阿拉伯人突破了可萨人防御并冲进了这座城市,大多数居民被屠杀或沦为奴隶,但有少数设法逃往北方[51]。尽管取得了成功,但阿拉伯人尚未击败可萨军队,并撤退到了高加索南部。

724年,阿拉伯将军al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami在库拉河和阿拉斯河之间的漫长战斗中击败了可萨人,进而攻占第比利斯,使高加索伊比利亚归穆斯林所有。726年,可萨人在一位名叫巴尔吉克的王子的率领下发动反攻,对高加索阿尔巴尼亚和阿塞拜疆进行了大规模入侵。到729年,阿拉伯人失去了对外高加索东北部的控制,再次进入守势。730年,巴尔吉克入侵伊朗阿塞拜疆,并在阿尔达比勒击败了阿拉伯军队(马尔吉-阿尔达比勒战役),杀死了Al-Djarrah al-Hakami将军并短暂占领了该地。第二年,巴尔吉克在摩苏尔被击败并丧生。737年,Marwan Ibn Muhammad以寻求休战为幌子进入可萨领土,然后发动了一次突袭,可汗逃往北方,可萨投降[53]。阿拉伯人没有能力来影响外高加索地区的事务[53]。可汗被迫接受皈依伊斯兰教的条件,并臣服于哈里发,但这一和解并未长久,由于倭马亚内部的不稳定和拜占庭的支持,三年之内可萨人重获独立[54]。有人猜想可萨人早在740年就采纳了犹太教,正是基于该历史背景,即在作为面对哈里发和东罗马时使用犹太教来确立其独立性,同时也符合亚欧大陆居民普遍皈依一种世界性宗教的潮流[注 12]。

Remove ads

9世纪,瓦良格人已形成一个强大的军-商系统,开始南下侵扰可萨人及其保护国(伏尔加保加利亚)控制下的水路,部分原因是为了经可萨-伏尔加保加利亚贸易区流向北方的阿拉伯白银[注 13],另一部分原因则是皮毛和铁制品贸易[注 14]。北方商队行经阿的尔时,和行经东罗马的赫尔松时一样,会被收取什一税[55]。斯拉夫人、伏尔加芬人和楚德人可能因此而联合起来形成罗斯国家,来保护其自身利益免受可萨苛捐杂税的影响。有人认为罗斯汗国的形成正是模仿了可萨汗国,瓦良格首领最早在830年就使用了“可汗”的称号,这一称号后来还继续用来称呼基辅罗斯的大公,而基辅罗斯首都基辅可能也是可萨建立的[56][57][注 15][注 16]。此外可萨从830年左右开始自主铸币,萨尔科勒堡垒的建造获得了拜占庭的技术支持(拜占庭当时是可萨的盟国),这可能是为了抵御北面的瓦良格人和东面草原的马扎尔人[注 17][注 18]。到了860年,罗斯人已抵达基辅并通过第聂伯河到达君士坦丁堡[60]。

同盟关系经常发生变化。拜占庭受到瓦良格罗斯袭击者威胁,会为可萨提供帮助,而可萨则时而允许北方人通过其领土以换取一部分战利品[61]。从10世纪早期开始,由于附庸民族的起义以及前盟友的入侵加剧,可萨人常常多线战斗。草原上有佩切涅格人,北面则是实力不断增强的罗斯人,两者都不断削弱可萨汗国的朝贡体系,可萨和平岌岌可危[62]。根据一位不知名的可萨人写给一位身份不明的犹太人的书信,可萨统治者与一个五国联合军队展开了战斗,这个联合军队可能是受到拜占庭的怂恿[注 19]。尽管可萨取得了胜利,但他的儿子遭遇了又一轮入侵,这一次敌人是阿兰人,阿兰人首领皈依了基督教并与利奥五世的拜占庭结盟。

可萨原本控制第聂伯河中游并向那里的东斯拉夫部落收取贡品;880年左右,随着诺夫哥罗德的奥列格从瓦良格人手里取得基辅,可萨对这一地区的控制减弱[63]。可萨人最初同意罗斯人沿着伏尔加河进行贸易并南下掠夺(见罗斯人的里海远征)。根据阿拉伯历史学家马苏第的说法,可汗同意的条件是罗斯人给予他们一半的战利品[61]。然而,913年,也就是拜占庭与罗斯达成和平协议两年之后,在可萨的默许下,瓦良格人向阿拉伯人的领土进军,导致花剌子模伊斯兰卫队向可萨统治者发出请求,要求允许他们对回程中的罗斯分遣队进行反击,目的是报复罗斯的劫掠给他们的穆斯林同胞造成的暴力伤害[注 20]。罗斯的军队遭遇彻底溃败并被屠杀[61]。可萨统治者向罗斯人关闭了南下伏尔加的通道,由此引发了一场战争。960年,可萨统治者在一封信中提到了与罗斯关系的恶化:“我守卫河口,阻止乘船前来的罗斯人进入大海攻击阿拉伯人,也阻止任何敌人走陆路进入杰尔宾特。”[注 21]。

罗斯军阀向可萨汗国发动了多次战争,直捣里海。一封书信中讲述了一位HLGW(最近被确认为切尔尼戈夫的奥列格)攻击可萨并被可萨将军击败的故事[64]。可萨与东罗马帝国的同盟在10世纪初期开始崩溃,两者可能在克里米亚发生冲突,到了940年东罗马皇帝君士坦丁七世在《帝国行政论》中思考了如何孤立并攻击可萨。同期,拜占庭开始尝试与佩切涅格人和罗斯结盟,并取得了不同程度的成功。斯维亚托斯拉夫一世最终在960年左右摧毁了可萨帝国的军队,并接触了高加索地区的切尔克斯人[注 23],随后又回到基辅[66]。首都阿的尔于公元968或969年左右陷落。

在罗斯编年史中,对可萨的征服与弗拉基米尔一世在986年的皈依有关[67]。根据《往年纪事》一书的记载,986年弗拉基米尔一世要决定基辅罗斯人信仰哪种宗教时,可萨犹太人也在场[68]。他们是已定居在基辅的犹太人,还是犹太可萨残余政权的密使,这一点不明确。接受一种“有经者”的宗教(即犹太教、基督教、伊斯兰教)是与阿拉伯人达成任何和平协议的一条先决条件,此前阿拉伯人已派遣保加尔使节到达基辅[69]。

在阿的尔被洗劫后不久,一个到访这座城市的旅客写道,葡萄园和花园已被夷为平地,土地上没有葡萄或葡萄干,没有东西可以施舍给穷人[70]。可能有人曾尝试重建该城,因为后来有两位穆斯林地理学家(Ibn Hawqal和al-Muqaddasi)都提到了这座城市,但在比鲁尼时代(1048年),它已是一片废墟[注 24]。

Remove ads

尽管Poliak认为可萨王国并没有完全屈服于弗拉基米尔一世的军事行动,而是一直维持到1224年蒙古征服基辅罗斯[71][72],大多数人认为,罗斯-乌古斯的联合行动使可萨遭受了毁灭性的打击,可能使大量可萨犹太人逃亡[73],充其量只有一个小残存国家留下来。除了一些地名外,可萨几乎没有留下任何痕迹[注 25],其大部分人口无疑被后继部落所吸收[74]。穆卡达西于985年左右写到里海以外的可萨是一个“祸患和肮脏”的地区,那里有蜂蜜、许多绵羊和犹太人[75] 。东罗马历史学家克德雷诺斯提到1016年罗斯-拜占庭联合进攻了可萨,击败了其首领Georgius Tzul(这一名字暗示他是基督教徒),这一历史记录总结道,在Georgius Tzul被击败之后,可萨统治者不得不请求和平与臣服[76]。1024年,切尔尼戈夫的姆斯季斯拉夫(弗拉基米尔的一个儿子)企图对基辅恢复一种“可萨式”的统治[66],率领一支包括“可萨人和卡索斯人(即切尔克斯人)”在内的军队向他的兄弟雅罗斯拉夫行进,被击退。伊本·艾西尔提到公元1030年“库尔德人在Faḍlūn the Kurd的带领下对可萨发动突袭”,10,000名库尔德士兵被后者击败,这被视为可萨残存政权存在的证据,但俄罗斯东方学家巴托尔德认为这里所说的可萨人实际上是格鲁吉亚人或阿布哈兹人[77][78]。据传,一位名叫切尔尼戈夫的奥列格的基辅大公曾于1079年被“可萨人”绑架,并被运往君士坦丁堡,尽管大多数学者认为这是指当时在本都地区占主导地位的库曼-钦察人或其他草原民族。切尔尼戈夫大公的儿子在1080年代征服了特穆塔拉干后,就给自己冠以“可萨人的执政官”之称[66]。据说,1083年奥列格在其兄弟被可萨人的盟友库曼人杀害后,对可萨人进行了报复。1106年与这些库曼人再次发生冲突之后,可萨人从历史上淡出[76]。到13世纪,他们的故事在俄国的民间传说中只是作为“犹太人之乡”里的“犹太英雄”而流传下来[79]。

12世纪末,一位德国拉比雷根斯堡的佩塔基亚到访了他称之为“可萨利亚”的地方,除了描述他们不停哀悼、一片荒凉中的极简(某个宗派)生活外,别无其他评论[80]。提到的宗派似乎是犹太教卡拉派[81]。方济各会传教士鲁不鲁乞在曾经是可萨首都所在地的伏尔加河下游只发现了贫困的牧场[82]。柏郎嘉宾时任罗马教皇驻贵由朝廷的使节,他曾提到一个未经证实的犹太部落,布鲁塔基,可能在伏尔加河地区;尽管人们把这一部落与可萨人联系了起来,但唯一的关系仅仅是犹太教的归属[83]。

十世纪的琐罗亚斯德教著作登卡德记录了可萨政权的衰落,并将其归因于“假”宗教对可萨力量的削弱[注 26]。可萨的衰落与东方河中地区萨曼王朝的衰落是同时代的,两个事件都为塞尔柱帝国的崛起铺平了道路,而塞尔柱帝国的崛起传统都提到了可萨人的联系 [84][注 27]。继承政权都不再能抵御东方和南方游牧民族扩张的压力。到了1043年, 基马克部落和钦察部落向西挺进,给乌古斯人带来压力,乌古斯人又将佩切涅格人向西推向拜占庭的巴尔干省份[85]。

尽管如此,可萨利亚还是给新兴国家以及一些传统和制度上留下了自己的印记。更早之前,利奥三世的可萨妻子将可萨人独特的卡夫坦长袍和骑马习惯引入了东罗马宫廷,并作为一些庄重的元素用于帝国服饰中[注 28]。此外,基辅罗斯有序的继承等级体系可以说是通过罗斯汗国而沿袭自可萨汗国[86]。

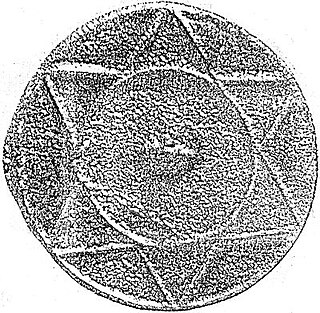

本都地区的原始匈牙利(马扎尔人)部落虽然可能早在839年就威胁了可萨,但仍实行自己的体制模式,例如kende-kündü和gyula分别管理实际事务和军事事务的双重统治体系,同时成为可萨人的朝贡国。可萨汗国的异见团体卡巴尔人与马扎尔人一起向西迁移到潘诺尼亚。匈牙利的部分人口可以看作是延续可萨传统的继承者。拜占庭曾称匈牙利为西图尔基亚,与东部的图尔基亚——即可萨利亚相对。阿尔帕德大公的后裔里产生了中世纪的匈牙利国王,而卡巴尔人则保留了更长的传统,且被称为“黑马扎尔人”(fekete magyarság)。塞尔维亚小镇Čelarevo的一些考古学证据表明卡巴尔人信奉犹太教[87][88][89],因为士兵坟墓里发现了带有犹太符号的文物,如犹太教灯台、羊角号(犹太教徒礼拜时用的)、香橼果(一种柠檬)、棕榈枝、熄烛罩、集尘器、希伯来语铭文和一个大卫之星相同的六芒星[90][91]。

可萨汗国不是从第二圣殿被毁(67–70年)到以色列建立(1948年)之间唯一存在过的一个犹太国家。希木叶尔王国也曾于4世纪接受犹太教,直到伊斯兰教兴起[92]。

可萨汗国早在犹大·哈列维的时代就曾激发犹太人重返以色列的弥赛亚愿望[93]。12世纪初期的埃及,一个名叫Solomon ben Duji,通常被认为是可萨犹太人[注 30],试图倡导犹太人的解放并呼吁所有犹太人重回巴勒斯坦,写信给许多犹太人社区争取支持。他最终移居库尔德斯坦。几十年后他的儿子梅纳赫姆自称弥赛亚,为此组建了一支军队,占领了摩苏尔以北的阿马迪耶堡垒。他的计划遭到拉比权威的反对,在睡眠中被毒死。有一种理论认为,当时还只是装饰图案或魔法纹章的大卫之星,就从梅纳赫姆的使用之后,开始在犹太晚期传统文化中成为民族价值的象征。

“可萨”一词作为民族名最后被使用是13世纪北高加索的一个信仰犹太教的民族[94]。可萨流散社区的性质(犹太教或者其他宗教)还存在争议。Avraham ibn Daud提到他在1160年左右遇见过来自西班牙托莱多的可萨裔拉比学生[95]。可萨社会在不同地方继续存在。许多可萨雇佣兵进入了伊斯兰哈里发和其他国家的军队。中世纪君士坦丁堡的文献里表明了加拉塔郊区可萨社区与犹太人混居的情况[96]。可萨商人活跃于12世纪的君士坦丁堡和亚历山大港[97]。

一些信奉犹太教的可萨人可能加入了中欧犹太社区。许多讲突厥语的犹太民族的代表,如卡拉伊姆人和克里姆查克人,认为自己是可萨人的后裔。北高加索的一些民族,特别是库梅克人,可能有可萨人的根源。

可萨人也是哈萨克族族源之一。

Remove ads

宗教

格鲁吉亚的阿拉伯圣徒第比利斯的阿波于779-780左右在可萨王国境内皈依了基督教,他将本地可萨人描述为无宗教[注 31]。一些史料则称萨曼达尔大多数居民是基督徒[注 32],也有史料说大多数人是穆斯林[注 33]。

可萨人皈依犹太教的事件,既有外部史料的记录,又可见于可萨书信,尽管也存在一些疑点[99]。希伯来文本的真实性曾长期受到质疑[注 34],但现在专家们普遍认为它们要么是真实的,要么反映了可萨内部文化传统[注 35][注 36][注 37][101]。另一方面,关于皈依的考古学证据则依然难以捉摸[注 38][注 39],可能反映考古挖掘不够完整,或者说明真正皈依犹太教的阶层很少[注 40]。草原部落皈依某个普世宗教是一个得到了很好证实的现象[注 41],可萨皈依犹太人,虽然比较反常,但也不应该是罕见的[注 42]。其他学者则断言可萨精英统治阶层皈依犹太教一事从未发生过;一些学者[注 43]对皈依的故事不屑一顾,认为其只是传说[99][104]。

据史料,来自伊斯兰世界和东罗马帝国的犹太人曾移民至可萨,以逃脱希拉克略、查士丁尼二世、利奥三世和罗曼努斯一世时期的宗教迫害[105][106]。英国历史学家西蒙·沙玛认为,在这些宗教迫害之后,巴尔干半岛和克里米亚等地,特别是希腊潘提卡彭的犹太社区,迁至宗教更为宽容的可萨,加入那里的亚美尼亚犹太社区。他认为,开罗藏经库残篇清楚地表明,犹太化的改革扎根于整个可萨人口[107]。皈依的模式是一位精英阶层首先接受新宗教随后民众大规模接受该宗教,民众对于强迫改宗往往是抗拒的[108]。大规模改宗的一个重要条件是定居的、城市化的国家,在城市里基督教堂、犹太会堂和清真寺提供了宗教中心,这和开放的大草原上自由的游牧生活方式相悖[注 44]。伊朗的高加索犹太人的一个传说声称他们的祖先使可萨人皈依了犹太教[109]。可追溯到16世纪意大利拉比Judah Moscato的一个传说则将其归功于Yitzhak ha-Sangari[110][111][112]。

皈依的时间和精英阶层以外的影响程度[注 45],后者不受一些学者的重视[注 46],这两点都还很有争议[注 47],但在740年到920年之间的某个时候,可萨皇家和贵族家庭似乎皈依了犹太教,部分原因可能是为了转移阿拉伯人和东罗马人要求他们皈依伊斯兰教或基督教的压力[注 48][注 49]。

在八世纪中叶,可萨王公从萨满教皈依犹太教(具体是卡拉派犹太教)。大约740年可萨可汗信奉犹太教,由一名有犹太人血统的将军布蓝倡导下接受(成为国教),一部分平民跟进,但平民多是穆斯林与基督徒。

十世纪时阿拉伯人说他们已与犹太人无异。在十一世纪受基辅罗斯人,东罗马帝国与佩切涅格人攻击下覆灭,现在的克里米亚从前称可萨利亚,很多民族称呼里海为可萨海。势力最大时至摩苏尔。

965年,伊斯兰历史学家伊本·阿希尔提到,受到乌古斯人攻击的可萨人向花剌子模求援,但因为他们在花剌子模眼中是“卡菲勒”,故遭到拒绝;据说可萨人因而皈依了伊斯兰教,于是,花剌子模军事协助可萨人驱逐了乌古斯人(由称为艾尔西亚的佣兵协助)。根据伊本·阿希尔的说法,这件事使得可萨的犹太国王皈依了伊斯兰教[69]

伊本·法德兰特别讲述了一起事件,其中可萨国王摧毁了阿的尔一座清真寺的尖塔,以报复对Dâr al-Bâbûnaj的一座犹太教堂的毁灭,并据称他说,如果不是因为害怕穆斯林会对犹太人进行报复,他会做得更糟。

文化和制度

可萨人是欧洲突厥语部落中最文明的,他们曾有三个首都:

统治阶层是一群人数相对较少、民族和语言不同于被统治者的团体,被统治者主要有阿兰人和乌古尔突厥部落,他们在人数上超过可萨人[113]。可萨的可汗从被统治民族里娶妻纳妾,伊本·法德兰说可汗有25位妻子60个妾,宫廷也有阉人,这种做法影响了后来的匈牙利人与乌古斯人;可汗受到花剌子模禁卫军(称为艾尔西亚)的贴身保护[注 50][注 51]。但与这一地区其他政体不同的是,他们招募雇佣兵(被阿拉伯历史学家马苏第称为junûd murtazîqa)[114]。在帝国的顶峰时期,可萨人实行集中的财政管理,常备部队大约有7000-12000名士兵,在有必要时,可以从贵族的随员里招募储备兵,使其人数增至两倍或三倍[115][注 52]。关于常备部队的其他数字可多达10万。 他们控制着25至30个不同的民族和部落,并要求他们进贡,这些部落居住在高加索、咸海、乌拉尔山脉和乌克兰草原之间的广阔领土上[116],对内自治,对可萨纳贡,可萨将他们的统治者封为俟利发。可萨军队由汗伯克(Qağan Bek)领导,并由称为答剌罕的下属军官指挥。当汗伯克派出一支部队时,他们无论如何都不会撤退;如果被击败,每一个返回的人都会被杀死[117]。

定居区由称为吐屯的行政官员管理。在某些情况下,例如克里米亚南部的拜占庭城镇,通常会在另一政权的势力范围内为一个城镇委派一个名义上的吐屯。

据估计可萨汗国的人口除了统治者以外共有25到28个不同的族群。精英统治阶层则似乎是由9个部落/氏族组成,他们内部的民族成分也不是单一的,可能分别统治9个省份或公国[118]。至于种姓或阶级,有证据表明存在“黑可萨人”(ak-Khazars)和“白可萨人”(qara-Khazars)的区别,但该区别是种族层面的还是社会层面的并不明确[118]。10世纪的穆斯林地理学家伊斯塔克里提出白可萨人十分俊美,他们白肤、红发、蓝眼珠,而黑可萨人则皮肤黑黝黝的接近深黑,好像他们是“某种形式的印度人”[119]。许多突厥语国家也有类似的(政治层面的,而不是种族层面的)区分,“白色”的占统治地位的武士种姓和“黑色”的平民阶层。主流学者的普遍意见是伊斯塔克里错误理解了给这个群体的名称[120]。早期阿拉伯史料普遍把可萨人描述为白肤、蓝眸和红发[121][122]。唐朝典籍里通常被视为可萨统治阶层的“阿史那”可能是来自东伊朗语或吐火罗语里表示“蓝色”或“深色”的词——塞语:âşşeina-āššsena(蓝);中古波斯语:axšaêna(深色的);吐火罗语:Aâśna(蓝色或深色)[123]。可萨帝国崩溃之后,这一区分似乎依然存在。后来的罗斯编年史在描述可萨人在匈牙利的马扎尔化过程中扮演的角色时,将可萨人称为“白乌古尔”,将马扎尔人称为“黑乌古尔”[124]。对遗体(如头骨)的研究显示斯拉夫人、其他欧洲人和一些蒙古人的混合[120]。

外国商品的进出口以及对过境商品征税所产生的收入,是可萨经济的主要特征,不过据说可萨也生产了云母[125]。在游牧草原政体中,可萨汗国独特地发展了自给自足的Saltovo-Mayaki[126]经济——传统畜牧和广泛农业的综合体,一方面得以出口绵羊和牛,另一方面充分利用伏尔加河丰富的渔业资源,并进行手工艺品的制造,再加上因控制主要贸易路线而获得的丰富的国际贸易税收。可萨人还是穆斯林奴隶市场的两个重要参与者之一(另一个是伊朗的萨曼王朝),他们向穆斯林提供来自欧亚北部地区被俘的斯拉夫人和部落民[127]。从奴隶交易里获得的利益使可萨得以维持一支与花剌子模穆斯林军队对抗的常备部队。可萨首都阿的尔反映了一种分裂:西岸的哈拉赞生活着国王及其统治精英,约有4,000名随从;而东岸的伊蒂尔则居住着犹太人、基督教徒、穆斯林和奴隶以及手工艺者和外国商人[注 53]。执政精英在这座城市过冬,从春季到深秋则都在他们的田间度过。首都外的一片大型灌溉绿地,通过运河与伏尔加河的连接,那里的草地和葡萄园延伸约20法拉赫(约60英里)[82]。一边对商人征收关税,另一边对25到30个部落收取贡品和什一税,征收贡品有:黑貂皮、松鼠皮,剑,或皮革、蜡、蜂蜜和牲畜,具体取决于地区。贸易纠纷由阿的尔的一个商业法庭处理,该法庭由七名法官组成,犹太教徒、穆斯林、基督教徒各两名,还有一名异教徒[注 54]。

文学作品

诺贝尔文学奖获得者、塞尔维亚米洛拉德·帕维奇作家所著《哈扎尔辞典》一书,以词条释义的形式,从基督教、犹太教和伊斯兰教三种史料的角度讲述可萨人的历史,其中心主题就是可萨汗国大规模皈依的问题以及关于身份认同的真理的难确定性[128]。

注释

参考资料

参见

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads