墨西哥革命(西班牙语:Revolución Mexicana)是指1910年—1920年墨西哥各派系之间的长期流血斗争,以结束独裁统治、建立立宪共和国告终。革命后由革命制度党长期执政,直至2000年。

| 墨西哥革命 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

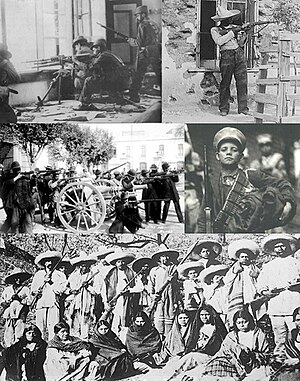

自左上顺时针:1913年在墨西哥城参与“悲惨十日”政变的叛军士兵、华雷斯城一间布满弹孔的房子、1910年参军的10岁童兵安东尼奥·戈麦斯·德尔加多、1911年一些墨西哥民兵与他们的妻子、在“悲惨十日”中保卫政府的马德罗派士兵 | |||||||

| |||||||

| 参战方 | |||||||

|

1910年–1911年: 波菲里奥·迪亚斯领导的联邦军 |

1910年–1911年: 马德罗派 奥罗斯科派 马贡派 萨帕塔派 | ||||||

|

1911年–1913年: 马德罗派 |

1911年–1913年: 贝尔纳多·雷耶斯领导的军队 费利克斯·迪亚斯 奥罗斯科派 马贡派 萨帕塔派 | ||||||

|

1913年–1914年: 维多利亚诺·韦尔塔领导的军队 |

1913年–1914年: 卡兰萨派 比利亚派 萨帕塔派 | ||||||

|

1914年–1919年: 比利亚派 萨帕塔派 费利克斯·迪亚斯领导的军队 贝努斯蒂亚诺·卡兰萨领导的军队 |

1914年–1919年: 叛乱派 | ||||||

|

1920年: |

1920年: | ||||||

历史

革命起因于人民对墨西哥总统波菲里奥·迪亚斯长期独裁统治的普遍不满。

1910年,迪亚斯想第7次连选连任总统,引起弗朗西斯科·马德罗以“反对连任党”领导人身份宣布自己为候选人。迪亚斯逮捕了马德罗,于6月举行假选举,宣布自己获胜。马德罗获释后,被迫流亡美国,在德克萨斯州圣安东尼奥发布“圣路易斯波托西计划”,号召11月20日举行起义。起义失败后,墨西哥国内的马德罗支持者,包括庞丘·维拉、埃米利亚诺·萨帕塔等人向政府发动战争。在北方,帕斯夸尔·奥罗斯科和庞丘·维拉动员他们的部队袭击政府驻军;在南方,萨帕塔开展反对地方政治首脑的流血斗争。1911年春,革命军攻克毗邻美墨边境的华雷斯城,加上一连串的军事胜利,迫使迪亚斯辞职,迪亚斯政权灭亡。革命派迎接马德罗回国成为总统。

然而马德罗政府从一开始就不稳定,马德罗并未实现革命前包括土地改革的承诺。萨帕塔对马德罗不立即将土地归还给被剥夺土地的印第安人表示愤怒,转而反对他。马德罗支持者奥罗斯科不满新政府改革步伐缓慢,也在北方发动了反政府运动。美国担心总统马德罗过于妥协,怕墨西哥内战影响美国的商业利益,也转而反对马德罗。当独裁者迪亚斯的侄子费利克斯·迪亚斯领导的军队和维克托里亚诺·韦尔塔指挥的联邦军队在墨西哥城发生冲突时,局势极为紧张。

1913年2月18日韦尔塔和迪亚斯在美国大使亨利·莱恩·威尔逊办公室签署所谓“大使馆计划”,商定共同反对马德罗,由韦尔塔出任总统。次日,马德罗被捕,被迫辞职,韦尔塔就任总统。数日后马德罗被暗杀。在北方,反对韦尔塔专横统治的力量也发展起来,庞丘·维拉、阿尔瓦罗·奥夫雷贡和贝努斯蒂亚诺·卡兰萨结成联盟。革命派的卡兰萨提出“瓜达卢佩计划”,要求韦尔塔辞职。

1914年春夏期间,起义军围攻墨西哥城,韦尔塔出走。8月20日,卡兰萨不顾维拉反对,宣布自己为总统。国家陷入混乱和流血的状态,直至维拉、奥夫雷贡和萨帕塔举行会议,一致认为维拉和萨帕塔之间的斗争使秩序无法恢复,并选举尤拉利奥·古铁雷斯为临时总统。

维拉支持古铁雷斯,奥夫雷贡则与卡兰萨联合,于1915年4月在塞拉西击败维拉。卡兰萨再次任总统。他主持起草1917年宪法,赋予总统以独裁权力,但规定政府有权没收富有地主的土地,保障工人权利和限制罗马天主教的权利。为了保持自己的权力,他清除异己,在1917年暗杀了萨帕塔。

1917年,卡兰萨修改了墨西哥宪法,使得墨西哥民主化。但当他在1920年企图破坏索诺拉的铁路工人罢工时,反对他的浪潮达到顶点,实际上他已众叛亲离。他在5月21日企图逃跑时被杀。阿道弗·德拉韦尔塔任临时总统,直到11月奥夫雷贡当选总统为止。许多历史学家认为,墨西哥革命在1920年即告结束。

然而,奥夫雷贡任总统,联邦军和叛军之间的冲突时有发生,墨西哥军事政变频频,直至1934年革命制度党改良主义者拉萨罗·卡德纳斯就任总统后才算平静下来。而革命后由革命制度党长期执政,直至2000年。

参见

参考文献

本条目包含来自公有领域出版物的文本: Chisholm, Hugh (编). Encyclopædia Britannica (第11版). London: Cambridge University Press. 1911.

- Chasteen, John. Born In Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New York:

- Documents on the Mexican Revolution Vol.1 Part 1. ed. Gene Z. Hanrahan. North Carolina: Documentary Publications, 1976

- Gonzales, Michael J. "The Mexican Revolution: 1910–1940" Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Hauss Charles, Smith Miriam, "Comparative Politics", Nelson Thomson Learning, Copyright 2000

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution, Volume 1: Porfirians, Liberals, and Peasants (1990); The Mexican Revolution, Volume 2: Counter-revolution and Reconstruction (1990)

- Lucas, Jeffrey Kent. The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

- Macias, Anna. "Women and the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1920." The Americas, 37:1 (Jul., 1980), 53–82.

- Meyer, Jean A. The Cristero Rebellion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976, pp. 10–15

- Quirk, Robert E. The Mexican Revolution and the Catholic Church 1910–1919. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973, pp. 1–249

- Reed, John. Insurgent México. New York: International Publishers, 1969. "[A] collection first published by John Reed himself in 1914 ... [of] John Reed's reportage of his days with the Mexican guerillas under Pancho Villa, establish[ing] him [i.e. Reed] as a top journalist of his time." -- From the pbk. book's back cover. ISBN 0-7178-0099-7

- Reséndez Fuentes, Andrés. "Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution." The Americas 51, 4 (April 1995).

- Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo. The Great Rebellion: Mexico, 1905-1924 (1980).

- Smith, Robert Freeman. The United States and Revolutionary Nationalism in Mexico 1916–1932. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972

- Snodgrass, Michael. Deference and Defiance in Monterrey: Workers, Paternalism, and Revolution in Mexico, 1890–1950. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-521-81189-9.

- Soto, Shirlene Ann. Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman. Denver: Arden Press, 1990.

- Swanson, Julia. "Murder in Mexico." History Today, June 2004. Vol.54, Issue 6; p 38–45

- Turner, Frederick C. "The Compatibility of Church and State in Mexico." Journal of Inter-American Studies, Vol 9, No 4, 1967, pp. 591–602

- Womack, John. Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (1968)

- Britton, John A. Revolution and Ideology Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Louisville: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995.

- Doremus, Anne T. Culture, Politics, and National Identity in Mexican Literature and Film, 1929–1952. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2001.

- Foster, David, W., ed. Mexican Literature A History. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

- Hoy, Terry. "Octavio Paz: The Search for Mexican Identity." The Review of Politics 44:3 (July, 1982), 370–385.

- Mora, Carl J., Mexican Cinema: Reflections of a Society 1896–2004. Berkeley: University of California Press, 3rd edition, 2005

- Myers, Berbard S. Mexican Painting in Our Time. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956.

- Noble, Andrea, Photography and Memory in Mexico: Icons of Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

- Noble, Andrea, Mexican National Cinema, London: Routledge, 2005.

- Orellana, Margarita de, Filming Pancho Villa: How Hollywood Shaped the Mexican Revolution: North American Cinema and Mexico, 1911–1917. New York: Verso, 2007

- Paranagua, Paula Antonio. Mexican Cinema. London: British Film Institute, 1995.

- Weinstock, Herbert. "Carlos Chavez." The Musical Quarterly 22:4 (Oct., 1936), 435–445.

- Knight, Alan. "The Mexican Revolution: Bourgeois? Nationalist? Or Just a 'Great Rebellion'?" Bulletin of Latin American Research (1985) 4#2 pp. 1–37 in JSTOR (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Wasserman, Mark. "You Can Teach An Old Revolutionary Historiography New Tricks Regions, Popular Movements, Culture, and Gender in Mexico, 1820–1940," Latin American Research Review (2008) 43#2 260-271 in Project MUSE

- Young, Eric van. "Making Leviathan Sneeze: Recent Works on Mexico and the Mexican Revolution," Latin American Research Review (1999) 34#2 pp. 143–165 in JSTOR (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Brunk, Samuel. The Banditry of Zapatismo in the Mexican Revolution The American Historical Review. Washington: April 1996, Volume 101, Issue 2, Page 331.

- Brunk, Samuel. "Zapata and the City Boys: In Search of a Piece of Revolution." Hispanic American Historical Review. Duke University Press, 1993.

- "From Soldaderas to Comandantes" Zapatista Direct Solidarity Committee. University of Texas.

- Gilbert, Dennis. "Emiliano Zapata: Textbook Hero." Mexican Studies. Berkley: Winter 2003, Volume 19, Issue 1, Page 127.

- Hardman, John. "Soldiers of Fortune" in the Mexican Revolution. "Postcards of the Mexican Revolution"

- Merewether Charles, Collections Curator, Getty Research Institute, "Mexico: From Empire to Revolution" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Jan. 2002.

- Rausch George Jr. "The Exile and Death of Victoriano Huerta", The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 42, No. 2, May 1963 pp. 133–151.

- Tannenbaum, Frank. "Land Reform in Mexico". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 150, Economics of World Peace (July 1930), 238–247.

- Tuck, Jim. "Zapata and the Intellectuals. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)" Mexico Connect, 1996–2006.

外部链接

- Library of Congress--Hispanic Reading Room portal, Distant Neighbors: The U.S. and the Mexican Revolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- EDSITEment's Spotlight: The Centennial of the Mexican Revolution, 1910-2010 from EDSITEment, "The Best of the Humanities on the Web"

- U.S. Library of Congress Country Study: Mexico (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Mexican Revolution of 1910 and Its Legacy (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), latinoartcommunity.org

- Women and the Mexican Revolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) on the site of the University of Arizona

- Stephanie Creed, Kelcie McLaughlin, Christina Miller, Vince Struble, Mexican Revolution 1910–1920 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Latin American Revolutions, course material for History 328, Truman State University (Missouri)

- Mexico: From Empire to Revolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), photographs and commentary on the site of the J. Paul Getty Trust

- Mexican Revolution, ca. 1910-1917 Photos and postcards in color and in black and white, some with manuscript letters, postmarks, and stamps from the collection at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Papers of E. K. Warren & Sons, 1884–1973, ranchers in Mexico, Texas and New Mexico (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), held at Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library at Texas Tech University

- Mexican Revolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), in the "Boys' Historical Clothing" website. This is an overview of the Revolution with a treatment of the impact on children.

- SMU's Mexic : graphs from the DeGolyer Library (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) contains dozens of photographs (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) related to the Mexican Revolution.

- Time line of the Mexican Revolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.