X连锁隐性遗传

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

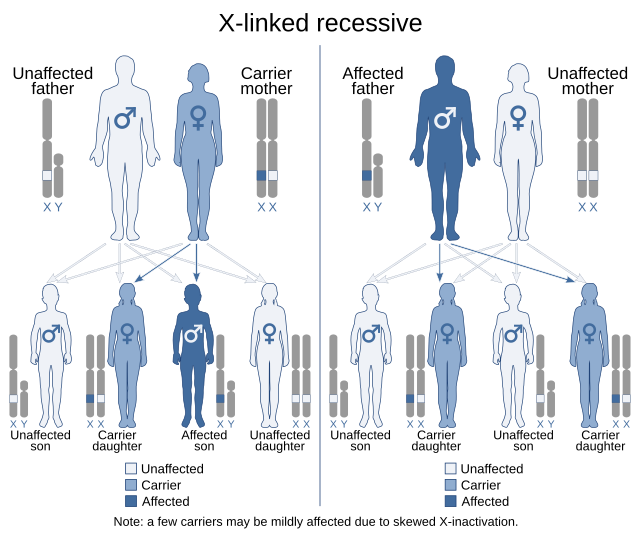

X连锁隐性遗传(X-linked recessive inheritance)是孟德尔遗传一种模式,其中X染色体基因突变导致表型总是在男性中表达(对于基因突变来说必然是纯合,因为有一条X和一条Y染色体),在基因突变纯合的女性中,参见合子。携带一份突变基因的女性是携带者。

X连锁遗传是指导致性状或疾病的基因位于X染色体上。女性有两X染色体,而男性有一X染色体和一Y染色体。只有一个突变拷贝的携带者女性通常不会表现出表型,尽管X染色体失活(倾斜X失活)的差异会导致携带者不同程度的临床表现女性,因为有些细胞会表达一个 X等位基因,而有些细胞会表达另一个。目前对已测序的X连锁基因的估计是499个,包括模糊定义的性状在内的总数是983个。[1]

继承模式

已隐藏部分未翻译内容,欢迎参与翻译。

In humans, inheritance of X-linked recessive traits follows a unique pattern made up of three points.

- The first is that affected fathers cannot pass X-linked recessive traits to their sons because fathers give Y chromosomes to their sons. This means that males affected by an X-linked recessive disorder inherited the responsible X chromosome from their mothers.

- Second, X-linked recessive traits are more commonly expressed in males than females.[2] This is due to the fact that males possess only a single X chromosome, and therefore require only one mutated X in order to be affected. Women possess two X chromosomes, and thus must receive two of the mutated recessive X chromosomes (one from each parent). A popular example showing this pattern of inheritance is that of the descendants of Queen Victoria and the blood disease hemophilia.[3]

- The last pattern seen is that X-linked recessive traits tend to skip generations, meaning that an affected grandfather will not have an affected son, but could have an affected grandson through his daughter.[4] Explained further, all daughters of an affected man will obtain his mutated X, and will then be either carriers or affected themselves depending on the mother. The resulting sons will either have a 50% chance of being affected (mother is carrier), or 100% chance (mother is affected). It is because of these percentages that we see males more commonly affected than females.

Pushback on recessive/dominant terminology

A few scholars have suggested discontinuing the use of the terms dominant and recessive when referring to X-linked inheritance.[5] The possession of two X chromosomes in females leads to dosage issues which are alleviated by X-inactivation.[6] Stating that the highly variable penetrance of X-linked traits in females as a result of mechanisms such as skewed X-inactivation or somatic mosaicism is difficult to reconcile with standard definitions of dominance and recessiveness, scholars have suggested referring to traits on the X chromosome simply as X-linked.[5]

Examples

Most common

The most common X-linked recessive disorders are:[7]

- Red–green color blindness, a very common trait in humans and frequently used to explain X-linked disorders.[8] Between seven and ten percent of men and 0.49% to 1% of women are affected. Its commonness may be explained by its relatively benign nature. It is also known as daltonism.

- Hemophilia A, a blood clotting disorder caused by a mutation of the Factor VIII gene and leading to a deficiency of Factor VIII. It was once thought to be the "royal disease" found in the descendants of Queen Victoria. This is now known to have been Hemophilia B (see below).[9][10]

- Hemophilia B, also known as Christmas disease,[11] a blood clotting disorder caused by a mutation of the Factor IX gene and leading to a deficiency of Factor IX. It is rarer than hemophilia A. As noted above, it was common among the descendants of Queen Victoria.

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which is associated with mutations in the dystrophin gene. It is characterized by rapid progression of muscle degeneration, eventually leading to loss of skeletal muscle control, respiratory failure, and death.

- Becker's muscular dystrophy, a milder form of Duchenne, which causes slowly progressive muscle weakness of the legs and pelvis.

- X-linked ichthyosis, a form of ichthyosis caused by a hereditary deficiency of the steroid sulfatase (STS) enzyme. It is fairly rare, affecting one in 2,000 to one in 6,000 males.[12]

- X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), which affects the body's ability to fight infection. XLA patients do not generate mature B cells.[13] B cells are part of the immune system and normally manufacture antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) which defends the body from infections (the humoral response). Patients with untreated XLA are prone to develop serious and even fatal infections.[14]

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, which causes nonimmune hemolytic anemia in response to a number of causes, most commonly infection or exposure to certain medications, chemicals, or foods. Commonly known as "favism", as it can be triggered by chemicals existing naturally in broad (or fava) beans.[15]

Less common disorders

Theoretically, a mutation in any of the genes on chromosome X may cause disease, but below are some notable ones, with short description of symptoms:

- Adrenoleukodystrophy; leads to progressive brain damage, failure of the adrenal glands and eventually death.

- Alport syndrome; glomerulonephritis, endstage kidney disease, and hearing loss. A minority of Alport syndrome cases are due to an autosomal recessive mutation in the gene coding for type IV collagen.

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome; variable degrees of undervirilization and/or infertility in XY persons of either sex

- Barth syndrome; metabolism distortion, delayed motor skills, stamina deficiency, hypotonia, chronic fatigue, delayed growth, cardiomyopathy, and compromised immune system.

- Blue cone monochromacy; low vision acuity, color blindness, photophobia, infantile nystagmus.

- Centronuclear myopathy; where cell nuclei are abnormally located in skeletal muscle cells. In CNM the nuclei are located at a position in the center of the cell, instead of their normal location at the periphery.

- Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMTX2-3); disorder of nerves (neuropathy) that is characterized by loss of muscle tissue and touch sensation, predominantly in the feet and legs but also in the hands and arms in the advanced stages of disease.

- Coffin–Lowry syndrome; severe intellectual disability sometimes associated with abnormalities of growth, cardiac abnormalities, kyphoscoliosis as well as auditory and visual abnormalities.

- Fabry disease; A lysosomal storage disease causing anhidrosis, fatigue, angiokeratomas, burning extremity pain and ocular involvement.

- Hunter syndrome; potentially causing hearing loss, thickening of the heart valves leading to a decline in cardiac function, obstructive airway disease, sleep apnea, and enlargement of the liver and spleen.

- Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, presenting with hypohidrosis, hypotrichosis, hypodontia

- Kabuki syndrome (the KDM6A variant); multiple congenital anomalies and intellectual disability.

- Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy; muscle cramps and progressive weakness

- Lesch–Nyhan syndrome; neurologic dysfunction, cognitive and behavioral disturbances including self-mutilation, and uric acid overproduction (hyperuricemia)

- Lowe syndrome; hydrophthalmia, cataracts, intellectual disabilities, aminoaciduria, reduced renal ammonia production and vitamin D-resistant rickets

- Menkes disease; sparse and coarse hair, growth failure, and deterioration of the nervous system

- Nasodigitoacoustic syndrome; misshaped nose, brachydactyly of the distal phalanges, sensorineural deafness

- Nonsyndromic deafness; hearing loss

- Norrie disease; cataracts, leukocoria along with other developmental issues in the eye

- Occipital horn syndrome; deformations in the skeleton

- Ocular albinism; lack of pigmentation in the eye

- Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; developmental delay and intellectual disability. Progressive liver damage, skin lesions, and brittle hair may also be seen

- Oto-palato-digital syndrome; facial deformities, cleft palate, hearing loss

- Siderius X-linked mental retardation syndrome; cleft lip and palate with intellectual disability and facial dysmorphism, caused by mutations in the histone demethylase PHF8

- Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome; coarse faces with protruding jaw and tongue, widened nasal bridge, and upturned nasal tip

- Spinal muscular atrophy caused by UBE1 gene mutation; weakness due to loss of the motor neurons of the spinal cord and brainstem

- Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome; eczema, thrombocytopenia, immune deficiency, and bloody diarrhea

- X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID); infections, usually causing death in the first years of life

- X-linked sideroblastic anemia; skin paleness, fatigue, dizziness and enlarged spleen and liver.

另见

参考

外部链接

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.