密特拉教

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

密特拉教(英语:Mithraism),又译米特拉教,也被称为密特拉密教、密特拉秘仪(英语:Mithraic mysteries),是一支以波斯主神密特拉为信仰中心的希腊罗马密教,大约1世纪至4世纪盛行于罗马帝国境内。[1]这支秘密宗教在罗马军队中很受到欢迎,[2]并且相当可能仅有男性教徒。

密特拉斯的崇拜者有一套深奥难解的七等级启蒙与公共仪式的圣餐制度体系。密特拉教的入教者自称syndexioi(音译:辛德希欧耶),意即“借着握手而团结(united by the handshake)”。[3]他们的集会在建于地下的神庙进行着,乃名为密特拉寺,也被翻译作“太阳式洞、太阳洞”;与其他希腊罗马神庙有所不同,密特拉寺的建筑刻意仿造密特拉斯宰杀牛的洞穴,[4]今日依然有许多座的密特拉寺被留存着。

许多的考古发现,包括集会地点、宗教遗迹和文物,贡献了现代有对于密特拉教的认识。[5]密特拉斯的圣像场景显示出祂从岩石中出生、宰杀公牛,以及与索尔神(太阳神)一起共享宴会等等的宗教形象。大约有420处场址已出土了与这项信仰有关的史料。发掘的文物项目当中约有1000个碑铭、700个屠牛场景(屠牛像)的例证,还有大约400个(密特拉教)其他古迹。[6]据估计在罗马至少会有680座密特拉寺。[7]然而,并没有来自这支宗教的书面记述或是神学理论留存下来;希腊文和拉丁文书籍中的碑文和节录或是信息传递的参考文献中只有零散的纪载,使得出土文物的解读仍然存在着问题和议论。[8]

古代罗马人认为这支秘密宗教具有波斯人或是琐罗亚斯德教徒的渊源。然而,自从1970年代初以来,占有主导地位的学术研究单位已经注意到波斯人的密特拉崇拜仪式和罗马人的密特拉密教之间的差异,因此被认为是一个不同于祆教的独特宗教。密特拉神在波斯与希腊、罗马之间信仰传播阶段的连续性被学者所讨论著。[9]密特拉教有时被认为与早期基督教相匹敌,[10]也有不少相似之处,譬如解放者-救世主、神职人员的等级制度(主教、长老、执事)、宗教性聚餐(圣餐)以及善与恶间的艰苦搏斗(屠杀公牛/受难)。

起源

请注意,为了防止翻译过程中原意流失,以下各章节涉及到有关文献引用将采取保留译文与原文两部分以供参照。

这支信仰神话的基本版本是由文献史料来证实的,然而,最主要地,则是借由在神庙之中的崇拜的偶像的描绘来做考证。不过后者难以做阐释的。

密特拉教神话传说可以肯定的版本是密特拉斯是从岩石之中出生的。[11]祂在祂自己的神庙之中的屠牛像上被描绘成猎捕和宰杀一头公牛(参见以下屠牛场景章节)。然后祂与司掌太阳神的索尔会面,索尔向密特拉斯表示服从。然后两尊神祇便握手,并且在公牛皮上用膳。对于与此有关的信仰知之甚少。[12]由欧布洛斯(Euboulos)与帕拉斯(Pallas)对这支宗教所著作的古代史册已经佚失了。[13]在拉丁文的密特拉教的宗教遗迹之中神明的名号确定是被尊为Mithras(密特拉斯,拉丁文原文中字尾有加‘s’),尽管Mithra这一字汇可能已被用于希腊文(Μίθρας)之中了。[14]

有些宗教遗迹则会显示出额外的神话情节。在杜拉·欧罗普斯的密特拉宗教绘画中(《密特拉宗教圣迹碑铭集成》〔Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae,缩写为CIMRM〕42号),故事是开始于众神之王朱庇特与巨人之间的战斗。接下来是一尊留着胡须的神祇横卧靠在一颗岩石上的神秘描绘,连同在上方有一棵树的叶子。这尊神祇有时被认为是俄刻阿诺斯。接着就描绘正规的密特拉教神话了。同样的情节也出现在来自于维鲁努姆(Virunum)的CIMRM 1430号中的浮雕里,以及在来自于德国的CIMRM 1359号中的浮雕里做为一个序幕。

在叙利亚境内位于哈瓦蒂(Hawarte, Hawarti or Huarte)密特拉寺内的宗教绘画中,有出现更进一步的神话场景。密特拉斯被描绘为在祂的脚下束缚了一只恶魔;而在另外一个场景之中,密特拉斯则被描绘为正打击著由恶魔所操控的城市。这些场景似乎遵循着正规的神话故事。

名号

“密特拉教”是一个现代(学术)规范下的一个专有名词。罗马时代的作家通过诸如“密特拉密教”、“密特拉斯的秘密宗教”或是“波斯人的秘密宗教”等叙述来提到祂。[9][15]现代资料有时将希腊罗马(密特拉)宗教称之为“罗马密特拉教”或是“西方密特拉教”以区别来自于波斯人的密特拉崇拜。[9][16][17]

密特拉斯乃古代波斯的真理与光明之神、太阳神、罗马密特拉教的主神,在英文文献中Mithras'为拉丁文形式,等同于希腊文的“Μίθρας”,[18]后来转入英文。)的名号是Mithra(密特拉)名号的另一种形式的写法,这乃是(源自于)古波斯神祇的名号[19][20]– 自从弗朗茨·库蒙的时期以来透过研究密特拉教的学者即是以这样关系联系所做出的理解。[21]这名号的一个早期希腊文型态之例证是借由公元前四世纪色诺芬的著作,即为《居鲁士之教育》一书中所得知而来的,这是一部撰述著波斯君王居鲁士大帝的传记。[22]

拉丁文或者是古典希腊文字形的确切型态是由于语法的变格过程而让字汇呈现了变化。有考古学的证据表明著在拉丁民族的崇拜者中将神祇名号的主格型态写为“Mithras”。然而,在这波菲利希腊文本De Abstinentia(为拉丁文写法;希腊文:«Περὶ ἀποχῆς ἐμψύχων»;汉译:《禁欲》)的著作之中,即有提到了现今已经失落的一段以欧布洛斯和帕拉斯为依据的密特拉密教佚史,这些的纂辑意味着这些作者将“Mithra”这个名号视为一个不变化的外来语词汇。[23]

在其他的语言中有关于密特拉神的名号还有包括著:

- 梵文中的密特拉,在《梨俱吠陀》之中是一个赞美的神的名号。[24][25][26]在梵文之中,“mitra”的意思是指“朋友”或者是“友谊”。[27]梵文中对这尊神明的名号的写法有两种:“Mitra”以及“Mitrah”,这是一尊与伐楼拿有关的吠陀神明。

- mi-it-ra-这词汇的型态,在一份西台和米坦尼王国之间的和平条约中有发现到,年代出于约公元前1400年左右。[27][28]

伊朗文的“Mithra”以及梵文的“Mitra”被认为是来自印度-伊朗语的一个词汇“密特拉”意思是契约。[29]

现代的历史学者毋论关于这些名号是否指称同一尊神明也有着概念上的分野。约翰·R. 亨尼尔斯(John R. Hinnells)曾写过Mitra/Mithra/Mithras作为在几种不同宗教中崇拜的单一神明。[30]另一方面,大卫·乌兰西(David Ulansey)认为屠牛的密特拉斯是一尊新的神明,祂在公元前一世纪开始被人们给崇拜著,并且向祂引用了一个古老的名号(来尊称祂)。[31]

玛丽·博伊斯(Mary Boyce),为一位古伊朗宗教的研究员,执笔写道尽管罗马帝国的密特拉教仿佛显得比历史学者以前所认为的伊朗(宗教)的内涵更少,不过仍然是“如同密特拉斯这名号独自的彰显著,这个内涵是有些重要的。(as the name Mithras alone shows, this content was of some importance.)”。[32]

证据和史料

密特拉教几乎是完全从物质文物和献纳碑铭中所得知的。总共,已经揭露了400多个与密特拉教相关的考古发现点,连同约1,000个献纳碑铭和1,150件雕塑。

很少有当代的书面文字史料来源,并且大部分留存下来都是教外人士的观点。提及密特拉教的资料可以在以下文献中找到:

- 普鲁塔克,《庞培的生平》(Life of Pompey)24;

- 波菲利,《在宁芙的洞穴》(On the Cave of the Nymphs)6、15-16、17-18、24-25;

- 波菲利,《戒除荤食》(拉丁文:De Abstinentia ab Esu Animalium;英文:On Abstinence from Animal Foods)4.16;

- 特土良(约公元200年),《在军队的花冠上》或者是《在士兵的花冠上》(On the Military Crown or On the Soldier's Crown)15;

- 奥利振(公元240年左右)《反驳克理索》(希腊文:Κατά Κέλσου;英文:Against Celsus)6.22。[a]

有关密特拉教之所以缺乏优良的文字书面资料主要原因是由于其作为一支秘密宗教的地位,其中圣像以及仪式的意义也唯有入教者才能够被准许知道的秘密。教内人士没有去记录他们宗教的详细内容,而且教外人士是对他们也是并不太了解的。这显然使得历史学家难以理解,所以目前关于密特拉教有很多教义仍然是未知的。

宗教中的圣像

很多关于密特拉斯的信仰只有从浮雕和雕塑才能得知。并且已经有很多人努力的尝试来解释这种史料。

密特拉斯崇拜在罗马帝国中的具体特点是神灵屠杀公牛的圣像。密特拉斯其他的圣像则被安座在罗马神庙内,譬如密特拉斯与索尔(罗马太阳神)一起的宴会,以及描绘着密特拉斯从岩石中诞生的圣像。但是屠杀公牛的圣像(屠牛像)总是在壁龛中央重要的位置。[33]用于重建这个宗教圣像背后神学理论的文本来源是非常稀少罕见的。[34](请参阅以下章节──屠牛场景的解译)

描绘神灵屠杀公牛圣像的做法似乎是明确地特定于罗马密特拉教。根据大卫·乌兰西所述,这个“或许是最重要的例证”有关于伊朗和罗马(宗教)传统之间明显的区别:“…没有证据显示伊朗的神明密特拉与屠杀公牛有任何关系。”。[35]

| |

|

|

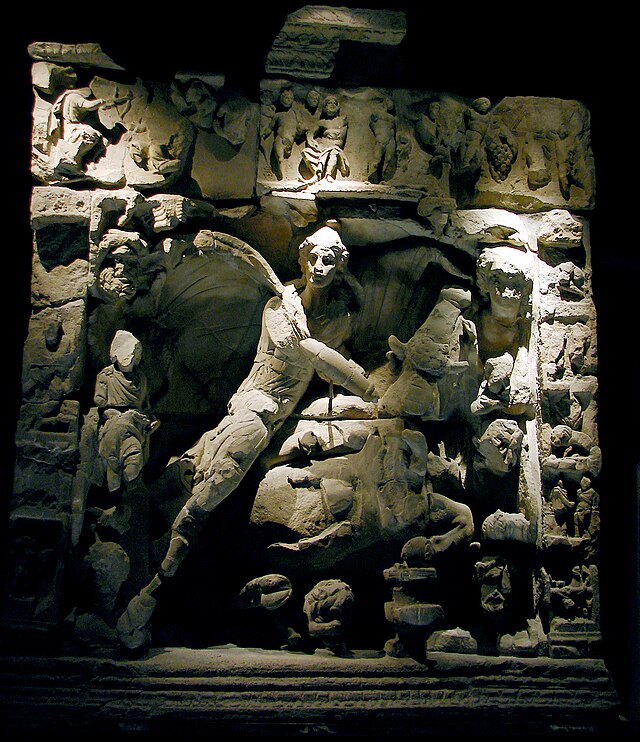

在每一座密特拉寺里面核心部分就是密特拉斯宰杀一头圣牛雕像的表现方式,称之为“屠牛像、屠牛神像”或者是香港人所称的“㓥牛像”(英文文献中的专有名词为:Tauroctony)。[36]

圣像的形式可能是以浮雕的方式呈现,或者是采用独立式的雕塑,并且在侧面的细节也许是存在或者是省略。这中心部分是密特拉斯穿着安纳托利亚地区的服装并且头上戴着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽;祂跪在一只筋疲力尽的[37]公牛身上,其中握住它(公牛)的鼻孔[37]是以祂的左手来行使的,并且祂右手拿着利器刺入公牛的颈部。当他这样做时,祂转过头来朝向索尔神像看了一下。一只狗和一条蛇的头伸向牛的血液。一只蝎子则箝住公牛的生殖器。一只乌鸦正在周遭飞舞或是坐在公牛身上。从公牛的尾巴看到三支小麦穗露出,有些时候的圣像造型则是小麦穗从伤口露出来的。这头公牛通常是白色的。神明以不自然的方式坐在公牛身上同时以祂的右腿压制住公牛的蹄并且左腿弯曲以及靠在公牛的背部或腹部上面。[38]两名火炬手各站于一侧,穿着同密特拉斯一样,考泰斯将祂的火炬向上者以及考托佩斯将祂的火炬向下者。[39][40]有时候圣像的造型中考泰斯与考托佩斯是带着牧羊人的曲柄杖来替代火炬。[41]

这项宗教仪式举行的地点是在洞穴里,密特拉斯带着公牛进入洞穴内,在对它猎杀之后,(密特拉斯)骑坐在它背上并且压制它的力量。[42]有些时候洞穴是由一个圆圈所围绕着,黄道十二星座的图像则是呈现在围绕洞穴的圆圈上面。在洞穴的外面,左上方,是司掌太阳的索尔,连同祂火焰般的头冠,祂通常驾驶着一辆四马双轮战车。一缕光线通常是射下来触及到密特拉斯。位于右上方的神祇则是卢娜,与祂的盈月在一起,祂可能被描绘为驾驶着一辆二马双轮战车(biga)。[43]

在一些圣像的描绘中,中央的屠牛像是由左方、上方以及右方的一系列附属场景所构成的整体造型,主旨在说明关于密特拉斯故事中的事件;密特拉斯从岩石出生、水的神迹、公牛的狩猎与骑乘、密特拉斯跪着谒见索尔、密特拉斯与索尔握手并且与祂分享公牛被支解后的膳食,以及乘坐一辆战车升向天空。[43]在某些情况下,就像这种斯达科(stucco,或译为:灰泥)圣像的例子则是位在圣塔普利斯卡(Santa Prisca或者是圣普利斯卡〔St. Prisca〕)密特拉寺里,寺中圣像的神明展现出英雄地裸体(heroically nude)。[44]其中一些浮雕被够造成以便于祂们(圣像)能够在一个轴上转动。在后面则是另一个形象的描绘,那是更加精致的宴会场景。这是标明著屠杀公牛场景是在(密特拉教的)宗教仪式第一部分之中被使用着,然后这(公牛屠杀场景浮雕)被转动后,跟着这二幕场景是在(密特拉教的)宗教仪式第二部分之中被使用着。[45]除了主要的崇拜圣像之外,许多的密特拉寺具有几个附带(secondary)的屠牛像,以及一些小型便于携带的版本,或许是意味着由私人所奉献的,(这类型的圣像)也是有被发现到。[46]

密特拉斯通常会被描绘成身边有两尊较小的神灵,服装穿着与密特拉斯相同,手持着火炬。这两位火炬手在密特拉斯宗教遗迹上被命名为考泰斯与考托佩斯。

在一些浮雕雕塑之中还有发现到的是一尊神秘的狮头形象的神像,祂或许可能被称为阿里曼纽斯(Arimanius)。

在密特拉教各种的宗教遗迹上有出现一名男性神祇留有络腮胡、斜倚着。这尊男神似乎就是俄刻阿诺斯,乃海洋的化身。

在某些宗教遗迹上可以遇见凯路斯这尊神祇的名号,例如CIMRM 1127号,其中考泰斯、考托佩斯、俄刻阿诺斯、凯路斯都有出现并被提到过的。密特拉密教的神灵凯路斯有时候被描绘成一只老鹰俯越在被标有与行星或黄道十二星座符号在一起的天球上面。[47]在密特拉密教的宗教背景(神灵的前后关系)下,祂(凯路斯)与考泰斯相关联的[48]以及也许可能是“永恒凯路斯”(Caelus Aeternus';汉译:“永恒的天空”)。[49]多罗·李维(Doro Levi)声称阿胡拉·马兹达在拉丁语中被呼唤为“永恒凯路斯·朱庇特”(Caelus Aeternus Iupiter)。[50]有些密特拉寺的墙壁特征是同俄刻阿诺斯与凯路斯一起的宇宙寓意之描绘。迪堡(Dieburg)的密特拉寺象征着在法厄同-赫利俄多穆斯(Phaeton-Heliodromus)之下同凯路斯、俄刻阿诺斯和特勒斯(罗马神话中的大地女神)一起的三部分世界。[51]

在屠牛像之后的第二项最重要场景于密特拉密教艺术之中就是所谓的“宴会场景”了。[52]宴会场景的特征是密特拉斯和索尔·无敌者在被屠杀的公牛皮上进行着宴会。[52]关于明确具体的宴会场景则是呈现在菲亚诺罗马诺地区的浮雕上,其中一名火炬手将商神杖指向祭坛的基座,商神杖的顶端似乎涌现出火焰来。罗伯特·图尔坎(Robert Turcan)认为由于商神杖是属于墨丘利(即希腊神话中的赫耳墨斯)所拥有的神器,并且在神话中墨丘利是被描述为一名普绪科蓬波斯(psychopomps,乃古希腊神话里负责接引死者灵魂的神祇们,也就是冥府使者),在这个场景中火焰的引发是指着人类灵魂的调遣并且就这件事情表达了密特拉密教的教义。[53]图尔坎也将这个事件与屠牛像联系起来:被屠戮的公牛血液已经在祭坛基座的地面上濡湿,并且从血液中灵魂被商神杖的火焰给引了出来。[53]

上图:密特拉斯从岩石中升起(现今珍藏于国立罗马尼亚历史博物馆);

右图:从岩石中出生的密特拉斯(大理石,公元180年~192年),出自于圣托·斯特凡诺·罗同多(Santo Stefano Rotondo,有时称之为San Stefano Rotondo或者是S. Stefano Rotondo)地区,罗马。

右图:从岩石中出生的密特拉斯(大理石,公元180年~192年),出自于圣托·斯特凡诺·罗同多(Santo Stefano Rotondo,有时称之为San Stefano Rotondo或者是S. Stefano Rotondo)地区,罗马。

密特拉斯被描绘为从岩石中出生。祂被显示为从岩石中出来的那时刻,就已经呈现在祂年轻时期的样貌,连同以一只手持着匕首以及另一只手持着火炬。祂是裸体的,与祂的双腿一同呈现出伫立的姿态,并且在祂的头上佩戴着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽。[54]

然而,(这样从岩石出生的圣像之)形象有了变化。有时候他被显示为如同一名儿童般地从岩石中出来,并且在某种情况下在祂一只手上握有一个球状物;有时会看到雷电。其中还有一些描述着火焰是从岩石再就是密特拉斯的帽子喷发出来的。有一座雕像的底座有穿孔以便能够作为喷泉的功能,并且在另一个底座则有水神的面像。有些时候密特拉斯还拥有着其他的武器像是弓与箭,并且还有伴随着动物们例如狗、蛇、海豚、老鹰、其他鸟类、狮子、鳄鱼、螯龙虾以及蜗牛在祂周围。在一些的浮雕上,有一尊留有胡须的神祇身份经鉴定为俄刻阿诺斯,祂乃是水神,并且有些地方则是为四风之神。在这些浮雕中,四大元素可能一起被召唤。有时候维多利亚(罗马神话中的胜利女神)、卢娜、索尔以及萨图恩也似乎担任著一个(重要任务的)角色。特别是萨图恩通常是被看到将匕首交付给予密特拉斯以便祂能够行使祂的伟大的事迹。[54]

在有些的描述中,考泰斯与考托佩斯也是有在场的;有时候祂们被描绘为牧羊人。[55]

在某些情况下,能被看到一只双耳瓶,并且有几个情况表现出了像(密特拉斯从)蛋出生或是(密特拉斯从)树诞生这样的变化。一些解释表明著密特拉斯的诞生是以点燃的火炬或是蜡烛(在宗教仪式上)被赞颂的。[54][56]

这支秘密宗教之中最具特色和人们对他们知之甚少、深奥难解的的特征之一就是经常在密特拉密教神庙里所发现到的裸体狮首人身像,经由现代学者以描述性的术语命名譬如leontocephaline或者是leontocephalus,在汉译之中都是“狮首、狮头”的意思;有时候leontocephaline被引申为狮头神。他被一条蛇给缠绕着(或者是被两条蛇所缠绕,像是一柄商神杖),蛇的头部通常靠在狮子的头上。狮子的口往往是敞开的,给予人一种威摄的印象。祂常常被人描绘成有两对翅膀、一双钥匙(有时是单支钥匙),以及握在祂手中的权杖。有些时候这尊神像是站在一颗刻有对角线交叉(diagonal cross)的球状物上。在这里所示的神像中,两对翅膀意味着四季的象征,并且在祂的胸部上则刻有雷电(希腊神话:宙斯/罗马神话:朱庇特的神器)。在神像的基座上是伏尔坎的锤子和夹钳、鸡,以及墨丘利的法杖(即是商神杖)。这相同的神像还有一种造型上的变化,然而是以人类的头部形象而不是狮子面像(lion-mask),也是有被发现到,但是很罕见。[57][58]

虽然动物头像的神祇在当时同时代的埃及和诺斯替神话的画像表示法之中是很普遍的,但是与密特拉密教的狮头神像完全相似的却还没有被发现到。[57]这尊神像的名号已经从专门的碑铭上被解读出来为阿里曼纽斯,乃是阿里曼名称的一种拉丁文形式——即为琐罗亚斯德教万神殿中的一名恶魔。阿里曼纽斯从碑铭上得知祂被认为在密特拉密教信仰之中显然是一尊神明,举例来说,在从《密特拉宗教圣迹碑铭集成》(CIMRM )所收录的图片中像是源自奥斯提亚的222号、源自罗马的369号,以及源自匈牙利潘诺尼亚(Pannonia)的1773号和1775号。碑铭上提到“阿里曼纽斯”为“deus(德乌斯)”,等于英文里“a god”、中文里“神明”的意思。[59]

有些学者将这狮头人身的神像鉴定为艾翁(或译为:埃安)、或者是祖尔宛、或者是克洛诺斯、或者是柯罗诺斯,而其他人则声称祂是琐罗亚斯德教之中阿里曼(拉丁文形式的)译名。[60]也有人推测著这尊神像是诺斯替教的造物主(Demiurge),(上帝之狮〔Ariel〕)伊达波思。[61]尽管狮头神像的确切身份被学者们所讨论著,在很大程度上认定着神明与时间和季节的变化有关。[62]一个例子是出自于西顿密特拉寺CIMRM 78号到CIMRM 79号。一位神秘主义术,D. J. 库珀(D. J. Cooper),抱持着相反的推测论点认为狮头神像并非神祇,而更准确地说是代表了在密特拉教之中的“精通”层次所达到的精神境界或是心灵状态,即为狮子等级。 [63]

仪式和礼拜

根据马腾·约瑟夫·费尔马歇仁所述,密特拉密教的新年以及密特拉斯的圣诞是在12月25日。[64][65]然而,罗杰·贝克(Roger Beck)非常地不同意(M. J. 费尔马歇仁的观点)。[66]曼弗雷德·克劳斯(Manfred Clauss)陈述说:“密特拉密教没有祂自己的公众仪式。无敌者生日的节庆,于12月25日举行,乃是一般普遍性的太阳节日,并且决不是特定于密特拉斯的密教(之节日)。”[67]密特拉密教之新的教徒被要求发起一项保守秘密与奉献(dedication)的誓言,[68]并且有些等级仪式是涉及到教义问答书(catechism)的背诵,在其中入教者会被询问到有关于起蒙入会象征意义的一系列问题,并且(入教者)必须回答明确的答案。有一项这样的教义问答书的例证,显然地是关于狮子等级(Leo grade),被发现在一份残缺不全的埃及莎草纸(P.Berolinensis 21196)上,[68][69]并写道:

译文:

…他将会说:’何处…?

…他是/(你是?)在那个方面(在那时/在那上面)茫然不知所措?’说:…说:’夜晚’。他将会说:’何处…?’…说:’所有的事物…’(他将会说):’…你称为…?’…说:’因为夏天…’…已经成为…他/它有着火热…(他将会说):’…你接受/继承了吗?’…说:’在坑里’。他将会说:’你在哪里…?…(说):’…(在那…)庙形坟墓。’他将会说:’你将会受束缚吗?’那(神圣的?)…(说):’…死亡’。他将会说:’为什么,已经束缚了自己,…?’’…这个(具有?)四条流苏。十分锐利并且…’…非常多’。他将会说:…?(说:’…因为/通过?)热和冷’。他将会说:…?(说):’…红色…亚麻布’。他将会说:’为什么?’说:’…红色边界;亚麻布,然而,…’(他将会说):’…已被包裹吗?’说:’救世主的…’他将会说:’父亲是谁?’说:’一尊(产生?)一切事物…’(他将会说):’(’如何?)…你成为了狮子’说:’由那…父亲的’。…说:’酒和食物’。他将会说’…?’

’…在这七之中—…原文:

'... in the seven-...

... He will say: 'Where ... ?

... he is/(you are?) there (then/thereupon?) at a loss?' Say: ... Say: 'Night'. He will say: 'Where ... ?' ... Say: 'All things ...' (He will say): '... you are called ... ?' Say: 'Because of the summery ...' ... having become ... he/it has the fiery ... (He will say): '... did you receive/inherit?' Say: 'In a pit'. He will say: 'Where is your ...?... (Say): '...(in the...) Leonteion.' He will say: 'Will you gird?' The (heavenly?) ...(Say): '... death'. He will say: 'Why, having girded yourself, ...?' '... this (has?) four tassels. Very sharp and ... '... much'. He will say: ...? (Say: '... because of/through?) hot and cold'. He will say: ...? (Say): '... red ... linen'. He will say: 'Why?' Say: '... red border; the linen, however, ...' (He will say): '... has been wrapped?' Say: 'The savior's ...' He will say: 'Who is the father?' Say: 'The one who (begets?) everything ...' (He will say): '('How ?)... did you become a Leo?' Say: 'By the ... of the father'. ... Say: 'Drink and food'. He will say '...?'

(可以说)几乎没有密特拉密教的经典或者是高度秘密仪式的第一手记述保存下来;[34]而关于前述的誓言和教义问答书则是例外,以及被称为密特拉斯圣仪(Mithras Liturgy,或翻译为:密特拉斯礼拜仪式)的文献(也是如此),(这份文献)乃是源自西元四世纪的埃及,其作为密特拉密教文献的地位已受到了包括弗朗茨·库蒙在内的学者所质疑。[70][71]密特拉寺的墙壁通常是有粉刷的,并且在这里往往拥有广泛地的宗教图画知识库保存着;还有这些,即连同著密特拉密教纪念碑上的碑铭一起,(因而)形成了密特拉密教文献的主要来源。[72]

尽管如此,由众多密特拉寺的考古学(研究)清楚地表明著大多数的仪式是与筵席有关 ——因为食用餐具和食物残渣几乎总是会被发现到。这些往往包括著动物的骨头再来就是非常大量的水果残留物。[73]尤其是大量樱桃核的存在会倾向于证实著仲夏(6月底、7月初)作为一个特别与密特拉密教庆祝活动相关的季节。这维鲁努姆《教徒名籍》(album),以刻着青铜名牌的形式,纪录了正是发生在公元184年6月26日的密特拉密教纪念节庆的欢宴。贝克认为在这个日期的宗教庆典表明著夏至被赋予了特殊重要性;但是一年的这个时段和在仲夏时太阳极大的古老认识(观点)正好相符合,同时也注意到像是利塔节(为凯尔特人的古夏至节)、圣约翰节前夕(St John's Eve),以及詹尼节(Jāņi,为拉脱维亚人庆祝夏至的节日)等具有同一原因的宗教象征性节庆。

为了他们的盛宴,密特拉密教的入教者会倚靠在沿着密特拉寺长边所安排的石制条凳上——通常可能会有15到30个食客的饭厅,但是很少会多于40多人。[74]相对应着(这样类型的)饭厅,或者是躺卧餐桌(triclinium,复数型态为:triclinia),在罗马帝国境内几乎任何神庙或宗教圣所的管辖区域被建筑在地面上,而且这样的厅室常常用在罗马人他们‘会社(clubs)’,或者是同僚团体(collegium,复数型态为:collegia)的定期宴席。正如同僚团体对于有资格加入他们会社而言,密特拉密教宴席对于密特拉教徒而言或许也是执行着相似的作用;事实上,由于罗马同僚团体的资格往往(严格地)只限于特定的家族、地方或传统行业,而密特拉教可能有部分社交聚会是作为提供著非严格限定会员条件的会社。[75]然而,密特拉寺的(寺院)规模不一定就能够代表教众人数的多寡。[76]

每一座密特拉寺在最深处的尽头会有几个祭坛,是位在屠牛像的圣像下方,并且还通常包含相当数量的附属祭坛,两者都在密特拉寺的主室(chamber)以及位于前室(the ante-chamber)或者是前厅(narthex)。[77]这些祭坛,其皆为标准的罗马样式,每个祭坛会带有从特定的入教者中所献纳的题词,特定的入教者向密特拉斯献纳祭坛“履行他的誓言(in fulfillment of his vow)”,乃因获得恩惠而向神明致谢。燃烧过的动物内脏残留物通常被发现在主要的祭坛上表明著祭品的定期使用。然而,密特拉寺通常显示出没有提供关于动物牺牲祭品的屠宰仪式(在罗马宗教中的一项高度专业化功能),[b]并可以依此推测著密特拉寺会为了他们与民间信仰的专业祭品执事(victimarius)[78]合作而去提供这项服务地安排。每日对着太阳致以祈祷三次,并且星期日是特别神圣的一天。[79]

密特拉教是否具有整体性与内部一贯的教义(对外人而言)是无法确定的。[80]其可能因地方的差异而有所不同的变化。[81]然而,在(从肖像学而言)圣像场景方面就相对地比较一致了。[43](密特拉教)其没有最主要显著的圣所或者是礼拜的中心;还有,虽然每一座密特拉寺都有(属于)祂们自己的官员和负责人员,但却没有中央的监督管理机构。在有些密特拉寺之中,比如位在杜拉·欧罗普斯的那座(密特拉寺),壁画描绘了携带卷轴的先知,[82]但是既没有提到过密特拉密教圣人的名称是已知的,也没有任何参考文献提供任何(有关于)密特拉密教经典或教导的头衔。众所周知的是入教者可以将他们的等级从这一座密特拉寺转移到另一座密特拉寺。[83]

现代文献中“Mithraeum(密特拉寺)”是一个现代新造的字汇,用以称呼密特拉信仰的神庙。古代的密特拉教徒将他们的神圣建筑称为“speleum”或者是“antrum”(洞穴)、“crypta”(地下过道或者是走廊〔underground hallway or corridor〕)、“fanum”(神圣或圣地〔sacred or holy place〕),乃至“templum”(神庙或者是神圣场所)。[84]从比较具体的研究资料指出,在意大利境内的碑铭显示出密特拉寺常常被称为“spelaeum”;而在意大利境外则被称之为“templum”。[85]现存的密特拉寺遗迹向我们展现了密特拉信仰的神圣空间的实体建筑结构,通常位在罗马帝国境内;尽管分布上的不均匀,以相当多的数量是发现在罗马、奥斯提亚、努米底亚、达尔马提亚、不列颠尼亚以及沿着莱茵河/多瑙河边界;而在希腊、埃及,以及叙利亚则不太常见。[86]

密特拉斯寺凹陷于地下、没有窗户,可以说非常独特。[87]室内的格局包含了一个中央过道,连同室内墙边两侧都有凸起的的一排长椅(podium)。[88]入口处常常会有一个前厅或者是前室,通常还会有用于准备或储存食物的附属厅室。密特拉寺往往是小规模的,外形不是特别的显眼,并且是廉价地建造;这支信仰教派通常比较喜欢创造一个新的中心,而不是扩大现有的中心。在城市里,密特拉寺可能是由一座公寓住宅大楼的地下室改造而成;在别的地方,他们可能是用挖掘的方法并将上方做成圆拱形的,或者是从天然洞穴来进行改造;由于无法负担做拱顶的石材开销,促使他们改采以板条和石膏做摹拟。密特拉寺之所以要如此建造,可以从波菲利的文献中找到说明,他摘引了失落的欧布洛斯手册[89]陈述著密特拉斯是在一个岩石的洞穴里被供俸著,一些学者推论密特拉寺象征着密特拉斯宰杀公牛的洞穴。[4]密特拉寺通常座落在靠近泉水或溪流之处;似乎一些密特拉密教的仪式需要用到淡水,并且水池通常被合并到建筑结构的格局中。[90]

根据沃尔特·布尔克特(Walter Burkert)所述,密特拉密教仪式的秘密性质意味着密特拉教只能在密特拉寺内实行。[91]然而位在蒂嫩(Tienen)的一些新发现显示出大规模筵席的证据,意味着密特拉教可能不像一般认为的那样具有隐密性。[76]

在其建筑的基本形式中,密特拉寺与来自其他信仰的神庙以及神龛而言可是完全不同的。在罗马宗教范围内的标准规范模式中,这神庙建筑的功能是作为神明的宅舍(此乃传承自古希腊人对于神庙建筑的观念),其用意是通过打开的门和柱状门廊能够来观察,在一个开放式的庭院中的祭坛上提供著供奉祭品的摆设;可能不仅能合宜地提供给崇拜的入教者,而且还可以提供给叩里朵雷斯(拉丁文:colitores,英译为:ordinary worshippers,汉译为:普通信徒)或者是未入教的朝拜者使用。[92]密特拉寺则正好与此是相反的。[93]

在《苏达辞书》“密特拉斯”的条目下,它陈述著“没有人是被准许加入他们(密特拉斯的秘密宗教)的,直到他将历经几次分等级的考验而应该显示出自己的圣洁和坚定。”。[94]圣额我略·纳齐安则指的是“在密特拉斯秘密宗教内的考验(tests in the mysteries of Mithras)”。[95]

进入密特拉教有七个启蒙的等级,其由圣杰罗姆所列出的。[96]曼弗雷德·克劳斯指出等级的数目,有七个位阶,必须联系到行星。在费利奇西穆斯(Felicissimus)的奥斯提亚密特拉寺中之的马赛克即有描绘出这些等级,与其象征符号一起其(符号象征)若非等级之象征就是仅乃行星的符号。这等级在旁边还有一份碑铭是他们表彰每个等级成为不同行星神祇所庇佑的状况。[97]按重要性的升序排列,这(七阶)启蒙的等级为:[98]

| 等级 (包含意译、音译两部分) |

象征符号 | 行星/守护神 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 渡鸦,有些中文译为大乌鸦;或音译科拉斯(Corax)、寇鲁斯(Corux)或者是库尔维克斯(Corvex) (即英文中的raven或者是crow) |

大口杯(beaker),商神杖。 | 水星/墨丘利 | ||||

| 新郎;或音译纽帕斯或者是宁福斯(Nymphus)、宁福布斯(Nymphobus) (即英文中的Bridegroom) |

灯,手摇铃,面纱,饰环或者是带状头饰(diadem)。 | 金星/维纳斯 | ||||

| 士兵;或音译迈尔斯(Miles) (即英文中的soldier) |

罗马行军包,头盔,枪矛,鼓,腰带,护胸甲。 | 火星/马尔斯 | ||||

| 狮子;或音译里欧或者是里奥(Leo) (即英文中的lion) |

罗马铁铲(batillum or vatillum),铁摇子(sistrum),[c]月桂花环,雷电。 | 木星/朱庇特 | ||||

| 珀耳塞斯或者是帕撒斯(Perses) (波斯人) ※详见表下的解说。 |

斯基泰短剑(akinakes or acinaces),弗里吉亚无边便帽,镰刀,镰刀状的月亮与星星,机弦袋。 | 月亮/卢娜 | ||||

| 赫利俄多穆斯或者是海路德米斯(Heliodromus) (太阳的信使〔sun-runner or sun-courier〕或者是太阳—旅行从仆) |

火炬,太阳神的圣像,赫利俄斯的鞭子,宽松长袍。 | 太阳/索尔 | ||||

| 教父;或音译佩特 (英译为:father,即父亲之意) |

圆盘饰(patera),主教冠,牧羊人的棍棒,石榴石或者是红宝石戒指,祭披(chasuble)或者是披肩,镶有金属线的精美长袍宝石饰物。 | 土星/萨图恩 | ||||

|

※在希腊神话之中,珀耳塞斯是埃塞俄比亚女王安朵美达与希腊英雄玻耳修斯的儿子,并且也天帝是宙斯之孙子。珀耳塞斯亦被认为是波斯人的先祖。[99]他与海洋宁芙珀耳塞(Perse)一起被留在科塞亚(Cossaea)。而关于波斯人起源的说法方面,借由类似于声音的相似性,珀耳塞斯乃被视为与帕萨尔加德部落的阿契美尼斯是同属一个人的。另外,阿契美尼斯是阿契美尼德王朝的同名祖先,他在公元前705年和公元前675年统治了伊朗南部。 | ||||||

- 请注意:在上表中,连结到宗教头衔或者是随身携带物仅仅是近似性的说明,因为作为一支口耳相传的秘密宗教信仰,鲜少可靠的历史参考文献有留存下来。然而,类似的当代文物已经确定了,并且那是位在奥斯提亚·安提卡所座落的费利奇西穆斯密特拉寺之中,一项西元二世纪的马赛克描绘了几个密特拉密教的器具和符号。

-

铲子,铁摇子,闪电。

-

剑,盈月,星星,镰刀。

-

火炬,头冠,鞭子。

-

圆盘饰,棍子,弗里吉亚无边便帽,镰刀。

在别处,像是位在杜拉·欧罗普斯(的密特拉寺)一样,密特拉密教的题字保存了已纪录的教徒名单,其中一座密特拉寺的入教者是以他们的密特拉密教等级命名的。而位在维鲁努姆,这教徒名单或者是《奉圣教徒名籍》(album sacratorum)被保留为铭刻的牌匾,随着入教的新教徒而逐年更新。通过前后参照交叉引用这些名单,其可以从这一座密特拉寺到另一座密特拉寺来追踪到某些入教者;并且也还能推测性地去鉴定与密特拉密教入教者一起在其他当代名单上的人士,像是兵役名册、有关非密特拉的宗教圣所皈依者的名单。祭坛和其他崇拜物品的奉献碑铭中也发现了入教者的名称。克劳斯在1990年总体的评论著,密特拉密教(的教徒)名称的刻写于公元250年以前只有约14%确认出入教者的等级──并因此质疑了传统观点即所有的入教者都属于七个等级之一。[100]克劳斯认为这些等级代表了不同阶级的祭司,sacerdotes。理查德·戈登(Richard Gordon)则坚持以前默克尔巴赫(Merkelbach)及其他人的理论,特别注意到像杜拉(Dura)这样子的例证,那里所有的名字都是与密特拉密教等级相关联的。有些学者主张这种做法可能会随着时间的推移而不同,或者是从这一座密特拉寺到另一座密特拉寺有所差异。

这最高等级“教父”是很大程度上在献辞和碑铭最常发现的──并且对于密特拉寺而言拥有几个具备这个等级的男子其似乎没有那么的异乎寻常。这pater patrum(英译:father of fathers;汉译:父亲的父亲,引申为教父之父)是经常找到的类型,其似乎表明了“教父”具有主要的地位。有几个人的例子可以说明,通常那些社会地位较高的人,进入密特拉寺(入教)具有“教父”地位──特别是罗马(帝国)在四世纪‘异教复兴’的期间。已经有人提出著(这样的说法是)有些密特拉寺可能会颁发荣誉“教父”地位给予有同情心、和蔼的高贵的人。[101]

当这入教者进入每一个等级的地位时似乎会被要求去接受着特定具体的严峻磨难或者是考验,[102]其包括涉及曝露于炽热、酷寒或者是具威胁性的险境。一处‘磨难坑(ordeal pit)’,可以追溯到西元三世纪初期,这已经在卡洛堡的密特拉寺获得了确认。关于(罗马)皇帝康茂德的残酷压迫之记录是描述到他自己的滑稽行径在于他通过以杀人形式颁布了密特拉密教启蒙考验的法令。[d]到了西元三世纪后期,这所颁布艰苦考验的法令似乎在严酷之中呈现缓和、减弱的趋势,因为‘磨难坑’被填平了。

被准许接纳而进入教团是连同了与“教父”一起握手(的象征性仪式),就像密特拉斯和索尔握手一样。这入教者乃因而被称之为辛德希欧耶(syndexioi,那些由握手团结的人)。该宗教术语被用于普洛菲璨西乌斯(Proficentius)的碑铭[3]以及被费尔米库斯·马特尔努斯在他所撰写的《错误的世俗宗教》( De errore profanarum religionum)一书中受到嘲讽,[103]那是一部西元四世纪基督教责难异教的著作。[104][e]在古代伊朗,握着右手是缔结条约的传统方式或者表示著双方之间的一些庄严谅解。[105]

在密特拉密教场景之中最为显赫的神灵行为,索尔以及密特拉斯,由在这信仰的等级制度中的两名最高级长官在仪式里所仿效,此即教父和赫利多俄穆斯(Heliodromus)。[106]入教者举行了圣礼餐宴,重现了密特拉斯与索尔的宴会。[106]

于美茵茨境内发现到一只杯子上的浮雕,[107][108]似乎描绘出密特拉密教启蒙(仪式)。在这一只杯子上,入教者 被描绘成被引导到一个位置,在这个位置上,“教父”将会打扮成密特拉斯以拉弓的姿势坐着。伴随入教者的是一位秘法家(mystagogue,神秘教义的解释者、引人入秘教者),他向入教者解释象征符号和神学。仪式被认为重新制定成为了所谓‘水的神迹’,在这神迹方面是密特拉斯发射出一道闪电打入岩石中,并于此刻由这岩石便因而喷出水来了。

罗杰·贝克假设了第三个(宗教)游行的密特拉密教仪式,这是基于美茵茨的杯子以及波菲利(两方的史料)。这个所谓太阳的信使之游行的特征是以 赫利多俄穆斯(Heliodromus)作重要角色,由两位代表分别代表考泰斯与考托佩斯的人士护送著(见下文)以及(游行队伍)前面是以一位士兵(Miles)等级的入教者为先导带领根据太阳运行测量的历程所制定(enactment)出围绕着密特拉寺的宗教仪式,其仪式之意旨是想要表示著宇宙。[109]

因此,有些人认为大多数密特拉密教仪式涉及到由入教者所重新设定在密特拉斯(神话)故事之中的一段情节,[110]而这神话故事其主要内容是:一、从岩石中出生;二、以箭矢射向岩石而从中喷出水来;三、公牛的屠宰;四、索尔向密特拉斯的服从;五、密特拉斯与索尔在公牛(皮)上举行宴饮;六、密特拉斯驾着一辆战车升向天空(heaven)。这个神话故事的一项显著特征(并且其定期描绘保存下来的浮花雕饰设置)是女性人物完全不在。[111]

密特拉密教似乎没有专业的神职人员。在宗教文物遗迹上也没有发现这样职位的特殊宗教术语。只有启蒙等级的名称以及正规标准长老会(collegium,例如:sacerdos〔祭司〕、antistes〔大祭司〕、hieroceryx〔英译为:‘sacred herald’;汉译为:神圣使者〕)的名称才有被确认及证实。并且也没有发现到关于profeta(先知)、pastophorus(主祭)、gallus(原文为“雄鸡”之意,代表警醒、悔改、革新的意涵,有光明战胜了黑暗寓意)或者是“fanaticus(全心全意投入宗教者、或是神职人员)”宗教名词的提及与引用。

有几个碑铭提到了“教父”(最高等级的入教者)或者是sacerdos(祭司)又或者是antistes(大祭司)作为负责人,并且似乎入教者的团体是集体地圣职者制度(sacrati)。波菲利(《戒除荤食》,4.16)陈述道密特拉密教的祭司被称之为“渡鸭(ravens)”,但是这可能与该入教者等级的名称产生混淆了。众所周知的,其他秘密崇拜信仰教派也以自己的投票表决方式推选出了他们的“祭司(priests)”,并且在一段有限的时期内任职服务,加上还有人也提议道密特拉密教的团体也是这样执行的。[112]

在库蒙的理论架构内认为这密特拉密教即是“罗马化的拜火教”,在他的杜拉文件论文之中库蒙声称[113]著──当时密特拉密教的祭司在别处被称为sacerdos(祭司)或者是antistes(大祭司)──位于杜拉一位密特拉密教的神职人员被人尊称为magus(法师,这一字汇的涵义为何──除了作为“方士(sorceror)”这个词之外──被希腊人与罗马人用来称呼琐罗亚斯德教的祭司,可以说是古波斯僧侣的一个尊敬称谓,希腊文为:μαγος、μαγουσαιοι,在英文之中还可以写作:Magusaeans或者是Magians)。[114]但是还没有证据能够证明这一点。虽然magus(法师)这个字汇确实出现了一次[115](CIMRM 61号;AE 1940.228,发现于1934年)且是位在杜拉密特拉寺的三个字的墙面宗教刻字之中,然而并没有迹象来表明其文字的意义。[116]

仅有男性的名字出现在现存刻写的教籍名单内。历史学家包括了库蒙和理查德·戈登所推论这个信仰只有男性才能入教。[117][118]

古代的学者波菲利有提到在密特拉密教仪式中的女性入教者。[2]然而,二十世纪初的历史学家A. S. 格顿(A. S. Geden)写道这可能是误解所致。[2]根据格顿所述,当时于东方的(宗教)信仰里妇女在仪式之中的参与并不陌生,在这种情况下于密特拉教之中军队的主要影响力(因为当时从军者都是男性的缘故)使其不太可能会有女性教徒出现。[2](而关于密特拉教中的女性)这一点最近由大卫·乔纳森(David Jonathan)提议著“妇女至少在(罗马)帝国的一些地方参与了密特拉密教团体。”。[119]

士兵们在密特拉教徒之中有很强的代表性,而且还有商贾、海关(customs)官员和小官僚。身份高贵的教徒鲜少,四世纪中叶的‘异教复兴’有来自于贵族或者是元老院的家族的入教者,但是自由民和奴隶仍旧占有相当大的人数。[120]

克劳斯认为借由波菲利的说法,(其观点为)开始加入狮子等级的人们(教徒)他们必须保持双手的纯洁(因为双手)从一切事物那所带来着痛苦和伤害并且(双手)是受到污染的,这意味着对教众的成员作出了道德的要求。[121](有关于密特拉教的道德规范也可以)在背教者尤利安的著作《凯撒》(Caesares)一书之中有提到了一段话是“密特拉斯的诫命”(找到线索)。[122]特土良,在他的专著《在军队的花冠上》之中记载道密特拉教徒于军队中正式免除了出于祝贺的冠冕这是在基于密特拉启蒙仪式上包括了拒绝递上花冠,因为“他们唯一的花冠是密特拉斯”。[123]

历史与发展

在亚历山大大帝征服后的几个世纪里,地中海世界的戏剧性统一为新宗教的成长创造了非常肥沃的土壤。例如,基督教是在这段时间内出现的创新宗教教派之一。然而,基督教的发展阶段有许多竞争的对手,以及在这其中最引人注目的之一是古罗马密特拉教的“秘密宗教”了。

在古代,书面记录提到了“the mysteries of Mithras(密特拉斯的秘密宗教)”,以及对于这支宗教的信徒,是作为“the mysteries of the Persians(波斯人的秘密宗教)”。[124]但是与波斯是否真的有任何连结的关系学术界则是有很大的争议了,还有关于这宗教的起源是相当朦胧不明的。[125]直到西元一世纪之前密特拉斯的秘密宗教是尚未盛行传布的。[126]独特的地下神庙或密特拉寺在西元一世纪的最后一刻却突然出现在考古学当中。[127]

在西元二世纪与西元三世纪期间,考古学上包括了许多大型的密特拉寺,其中有些在此期间有进行重建和扩大。当密特拉斯的信仰告终时,对这支秘密宗教很难再追溯到他们的足迹了。贝克陈述著“在这〔四〕世纪较早时期这支宗教如同(罗马)帝国自始至终一样的消亡了。(Quite early in the [fourth] century the religion was as good as dead throughout the empire.)”。[128]所以出自于西元四世纪关于密特拉教的碑铭就相当的稀少了。克劳斯则说明碑铭显示出由异教元老们列在碑铭上将密特拉斯(的秘密宗教)列为在罗马的信仰之一作为在上层集团掌权人物之中“异教复兴”的一部分。[129]在西元五世纪时已经没有可以显示这支信仰仍然存在的证据了。[130]

根据考古学家马腾·费尔马歇仁(Maarten Vermaseren)所述,出自于公元前一世纪科马基尼王国的证据表明了“对密特拉斯的敬仰(reverence paid to Mithras)”但是并没有提到“秘密宗教(the mysteries)”。[132]在由安条克一世(公元前69年~公元前34年)国王位于内姆鲁特山所建造的巨大雕像中,密特拉斯显示出没有蓄胡、戴着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽[1][133](或者类似的头饰,波斯冠状头饰〔Persian tiara〕)、穿着伊朗(帕提亚)服饰,[131]以及最初是坐在宝座上且位在其他神灵与国王本人的旁边。[134]在宝座的背面有一段希腊文碑铭,其中包括了阿波罗·密特拉斯·赫利俄斯(Apollo Mithras Helios)的名号在属格之中(希腊文原文:Ἀπόλλωνος Μίθρου Ἡλίου)。[135]费尔马歇仁还记述了有关于在公元前三世纪法尤姆的密特拉斯信仰。[136]R. D. 巴尼特(R. D. Barnett)则认为出自于大约公元前1450年的米坦尼国王萨乌什塔塔之皇家玉玺上就有描绘出密特拉斯屠牛像(tauroctonous)的图案了。[137]

这支秘密宗教的起源和传播在学者们之间进行了激烈的辩论并且对这些问题的看法有根本上的差异。[138]根据克劳斯所述密特拉斯的秘密宗教一直到西元一世纪以前尚未发展传播。[126]而根据乌兰西所述,密特拉密教其地址最早的证据是出现在公元前一世纪中期:历史学家普鲁塔克的说法是在公元前67年奇里乞亚(位于小亚细亚东南沿海的一个罗马行省)的海盗所执行的密特拉斯之“秘密仪式”。[139]然而,若是根据丹尼尔斯(Daniels)的说法,这些(的说法)是否与秘密宗教的起源有关还不清楚。[140]这独特的地下神庙或者是密特拉寺在公元前一世纪最后一刻突然出现在考古学之中。[127]

与密特拉密教相关的碑铭和宗教遗迹皆由马腾·J. 费尔马歇仁在两卷著作中编目,此即《密特拉宗教圣迹碑铭集成》(或者是原文的缩写为CIMRM)。[141]CIMRM 593号显示出的密特拉斯屠戮公牛被认为这是最早的宗教遗迹,而且是在罗马境内发现到的。没有注明日期,但是碑铭告诉了我们这确定是由阿尔息穆斯(Alcimus)所奉献出来的,他是提贝里乌斯·克劳狄乌斯·李维亚努斯(Tiberius Claudius Livianus or T. Claudius Livianus)的管家。费尔马歇仁和戈登相信着这位“李维亚努斯”就是一位已被确认的“李维亚努斯”他是在公元101年罗马禁卫军的指挥官,而这一点大概会可以找出最早的年代为公元98年~公元99年。[142]

出自于在罗马境内的第十五区埃斯奎利诺(意大利文:Esquilino;英文:Esquiline)上圣玛策林及圣伯多禄堂附近的一座祭坛或者是一大块直边的坚硬物体被(罗马)帝国一位其名为T. 弗拉菲乌斯·许癸努斯(T. Flavius Hyginus)的自由民给刻写成了双语的碑文,年代大约在公元80年~公元100年之间。其(祭坛)乃是奉献给予索尔·无敌者·密特拉斯(Sol Invictus Mithras)。[143]

CIMRM 2268号是一座损坏的基座或者是祭坛,其出自于下默西亚境内的诺维(Novae)/斯泰伦(Steklen),年代鉴定为公元100年,该祭坛有发现到考泰斯与考托佩斯(的浮雕)。

其他早期的考古学(史料)还包括了出自于公元100年~公元150年之间从维诺西亚(Venosia)而来由名为萨格里斯(Sagaris)的倡导者(actor)所刻写的希腊文碑铭;在西顿境内艾克门(Echmoun)的神庙之中发现了一座纪念石碑(cippus,古希腊罗马之纪念碑石)并且由M. 杜南德(M. Dunand)所公布出来。石碑刻有一段希腊文碑文,上面说这石碑是“由狄奥多图斯(Theodotus)献给了圣神阿斯克勒庇俄斯(Asclepios or Asclepius),密特拉斯在251年的ἱερεύς(英译:priest;汉译:祭司)”。石碑上刻写的时间251年乃是使用着西顿当地的时代纪年,相当于公元140年~公元141年。[144]也有列在《希腊铭文补编》(Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum)之中;[145]还有最早的军方碑铭,是由C. 萨奇狄乌斯·巴巴鲁斯(C. Sacidius Barbarus)所刻写的,乃为第十五阿波里纳利斯军团的百夫长,(该碑铭是)出自于多瑙河畔的卡农顿(Carnuntum),年代大概在公元114年之前。[146]

根据C. M. 丹尼尔斯(C.M.Daniels)所述,出自于多瑙河地区卡农顿碑铭是最早的密特拉密教题献,该处是同意大利一起成为密特拉教最早扎下(传教)根基的两个地区之一。[147]在罗马以外最早能确定年代的密特拉寺可追溯到公元148年。[148]位在凯撒利亚·马力提马的密特拉寺是在巴勒斯坦境内唯一可以被推断年代的一座(密特拉寺)。[149]

根据罗杰·贝克所述,经过证实在最早阶段(大约公元80年~公元120年)的罗马崇拜地点如下:[150]

从陶器上来确定时代的密特拉寺:

由献辞来确定时代的位址:

- 奈达/赫登海姆第一密特拉寺(Nida/Heddernheim I,上日耳曼尼亚)(CIMRM 1091号-1092号、1098号)

- 卡农顿第三密特拉寺(Carnuntum III,上潘诺尼亚)(CIMRM 1718号)

- 诺维(下默西亚)(CIMRM 2268号-2269号)[151]

- 伊斯克尔(Oescus,下默西亚)(CIMRM 2250号)

- 罗马(CIMRM 362号、593号-594号)

由文献参考来确定时代的位址:

- 罗马(斯塔提乌斯〔Statius〕的《底比斯战纪》〔Thebaid〕,1.719-20)

在克里米亚境内的刻赤附近已经挖掘出了由一尊神祇在公牛上拿着刀(屠牛像)的五个小型陶饰板,由贝斯寇(Beskow)与克劳斯所鉴定的年代是到公元前一世纪的下半叶,[152]以及由贝克所鉴定的年代则是由公元前50年~公元50年之间。这些可能是最早的密特拉教屠牛像,假如其被公认为是一尊密特拉斯的描绘的话(这一点就成立了)。[153]这尊屠戮公牛的神祇头戴一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽,但是由贝克和贝斯寇所描述的是除了这一点(弗里吉亚无边便帽)相同之外,在其他方面并不像是标准的屠牛像的宗教造型。关于这些(出土的)文物无法与密特拉密教相连接的另一项原因是在于最初这些陶饰板是被发现在一位女性的坟冢之中的。[154]

根据博伊斯(Boyce)所述,最早的文献参考引用到这支秘密宗教是由拉丁诗人斯塔提乌斯(的著作),公元80年左右,以及普鲁塔克(约公元100年)。[155]

这《底比斯战纪》(约公元80年[156])是一部由斯塔提乌斯所著的叙事诗,密特拉斯圣像在洞穴中,(祂的姿势)用手捉住牛角进行摔跤。[157]背景是向神明福玻斯的祷告。[158]这洞穴被描述为persei,在这种情况下persei通常会被翻译成Persian(波斯人、波斯的);然而,根据翻译者J. H. 莫兹利(J. H. Mozley)所述这字汇它字面的意思是Persean(珀耳塞斯的),指的即是珀耳塞斯(Perses),乃为玻耳修斯和安朵美达的儿子,[156]根据希腊传说所记载这位珀耳塞斯正是波斯人的祖先。[159]

希腊传记作家普鲁塔克(公元46年~公元127年)述说着“秘密宗教仪式…密特拉斯的(secret mysteries ... of Mithras)”被奇里乞亚的海盗所执行着,这(奇里乞亚)是位于安纳托利亚的东南沿海的罗马行省,他们是活跃于公元前一世纪,这是他当天在罗马执行的密特拉密教仪式的起源,其表述的全文如下:“他们还有提供奇特的祭品;我的意思是那些是奥林帕斯的;并且他们主持庆祝一些秘密宗教仪式, 在这之中密特拉斯的那些持续到这一日,最初是由他们所创制的。”[160]他提到了海盗是在米特拉达梯战争(罗马共和国和本都国王米特拉达梯六世之间的战争)的期间特别地活跃在这之中他们是支持着米特拉达梯六世国王的。[160]米特拉达梯和海盗之间的联盟也由古代历史学家阿庇安所提到过。[161]在维吉尔作于西元四世纪且由塞尔维乌斯所注释的评论上述说着庞培在南意大利境内的卡拉布里亚安顿了一些海盗。[162][163]不过这一点是否与这支秘密宗教的起源有关就不清楚了。[164]

历史学家狄奥·卡西乌斯(西元二至三世纪)讲述了亚美尼亚国王梯利达特斯一世向罗马所进行的国事访问期间对于密特拉斯的名号是怎样被称诵的,这是在尼禄皇帝在位的时期的历史事件。(梯利达特斯为帕提亚国王沃诺奈斯二世之子,并且他的加冕礼是由尼禄在公元66年所执行的,同时确认了帕提亚和罗马之间战争的结束。)狄奥·卡西乌斯对于梯利达特斯是这么写道的,因为他即将获得了他的冠冕,告诉著罗马皇帝他(尼禄)要尊敬他(梯利达特斯)“如同密特拉斯”。[165]罗杰·贝克认为这件插曲很可能是有助于密特拉教在罗马境内的出现而成为一个受欢迎的宗教。[166]

哲学家波菲利(西元三世纪~西元四世纪)在他的作品De antro nympharum(英译:The Cave of the Nymphs、On the Cave of the Nymphs;汉译:《宁芙的洞穴》、《在宁芙的洞穴》)提供了(关于)这支秘密宗教起源的描述。[167]援引引用欧布洛斯(的史册)作为他的资料来源,波菲利写道密特拉斯的原始神庙是一个天然的洞穴,其处拥有喷泉,这洞穴是琐罗亚斯德在波斯山脉中发现的。对于琐罗亚斯德来说,这个洞穴是整个世界的形象,所以他奉献这洞穴给了密特拉斯,世界的创造者。因此密特拉斯的神话说道他们的信仰是由琐罗亚斯德创立的。[168]之后在同样的作品之中,波菲利将密特拉斯和公牛与与行星和星座(star-signs)联系了起来:密特拉斯祂自己是与黄道十二星座中的牡羊座以及行星中的火星联系在一起,而公牛则是与金星联系在一起的。[169]

波菲利写作之时正好接近了这支信仰的消亡,而且现代学者罗伯特·图尔坎则对于波菲利关于密特拉教说法是正确的观点提出了质疑。他(波菲利)的情况是对于描述有关密特拉教徒所相信为何是有很大差距的,他们仅仅是由新柏拉图主义者在四世纪后期为了适应他们的思想去理解这支秘密宗教时加进他们的观念之陈述。[170]然而,默克尔巴赫和贝克则认为波菲利的著作“实际上彻底的带有这支秘密宗教教义的色彩”。[171]贝克认为古典学者忽略了波菲利的证据并且对波菲利的观点采取了不必要地怀疑。[172]根据贝克所述,波菲利的《在宁芙的洞穴》来自古代唯一明确的书面纪录这部著作告诉我们密特拉密教的意旨以及意旨的实现。[173]大卫·乌兰西发觉到波菲利是一位很重要(的人士)“证实…星体概念在密特拉教之中担任了重要的作用。”。[174]

在古代晚期,密特拉斯(Μίθρας )的希腊名号被发现在称为“密特拉斯圣仪”的文本中,属于《巴黎伟大巫术纸草文稿》( Paris Great Magical Papyrus;Paris Bibliothèque Nationale Suppl. gr. 574)的一部分;在这份文稿之中密特拉斯被赋予了“伟大神明(the great god)”的称号,并且被视为与太阳神赫利俄斯是等同的。[175][176]学者们之间有着不同的观点就是关于这份文本是否即为密特拉教这样的一个(宗教)表现方式。弗朗茨·库蒙则表明说这(文本)不是;[177]马文·迈耶(Marvin Meyer)却认为这(文本)是;[178]而汉斯·迪特尔·贝茨则将其视为希腊、埃及,以及密特拉密教传统的综合。[179][180]

如同古代其他的“秘密信仰”(厄琉息斯秘仪、俄耳甫斯教)般,密特拉密教维持着将其信仰的严格保密,也唯有他们的入教者才能够揭示。结果是,这支信仰的教义从未被写下来。然而,密特拉教徒将他们的神庙──密特拉寺用神秘的圣像来填满,这些丰富的宗教史料已经由考古学家所发掘出来了。到目前为止,所有试图解译该圣像的尝试已经证明是无效的。不过大多数专家都对密特拉斯圣像以某种方式来源于伊朗古代的宗教信仰这样一个模糊的假设感到满意了。

现代对于密特拉教的学术研究之中,在这种具有开创性的工作里面,学者大卫·乌兰西则提供了截然不同的理论。他认为密特拉密教的圣像实际上是一种天文学密码(astronomical code),而且那是这支信仰对于令人吃惊的科学发现之宗教回应。随着他调查的进行,乌兰西一步一步地识破了隐藏在密特拉密教圣像背后的奥秘。直到最后他能够揭示这支信仰的中心秘密:一个由宇宙最终性质的古老视野组成的秘密。

不过,以下章节将会从这项学术研究的先驱──弗朗茨·库蒙论起。

有关于密特拉斯的学术研究是从弗朗茨·库蒙这位学者开始的,他在1894年~1900年间以法语出版了两卷原始资料文本和宗教遗迹图像的汇编文集,法文原书名称为:Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mithra(英译书名为:Texts and Illustrated Monuments Relating to the Mysteries of Mithra;汉译书名:《与密特拉的秘密宗教有关的文本和宗教遗迹插图》)。[181]这部作品的部分英文翻译于1903年的时候出版,其书名题为:The Mysteries of Mithra;汉译为:《密特拉的秘密宗教》。[182]库蒙的假设,正如作者在他的专书前32页中总结的那样,那是一支罗马宗教乃为“拜火教的罗马形式”,[183]是属于波斯的国教,传播路径是从东方到西方的。他确认了古代雅利安的的神灵而祂这尊出现在波斯文献中与(出现在)吠陀赞美诗中的印度神明密多罗即是密特拉斯。[184]根据库蒙所述,密特拉神明来到了罗马“伴随着拜火教万神殿的大量继承。”。[185]库蒙认为着虽然传统“在西方经历了一些修改…其所遭受的改变在很大程度上是表面的”。[186]

库蒙的理论是开始在1971年所举行的第一届国际密特拉密教学术研究大会上受到由约翰·R. 亨尼尔斯以及R.L. 戈登的严厉批评。[187]约翰·亨尼尔斯不愿意完全否认伊朗起源的想法,[188]而写道:“我们现在必须得出结论是他的重建根本不会成立。其没有从伊朗的资料上获得支持并且实际上与作为祂们(密特拉教)现存文本中代表的传统思想相抵触。最重要,这是一个不符合实际罗马肖像学的理论重建。”[189]他商议了关于库蒙的屠牛场景之重建并表示道“以库蒙所提出关于密特拉斯的描绘不仅仅是由于在伊朗文本上的没有根据而是竟然与已知的伊朗神学有严重的冲突。”[190]由R.L. 戈登的另一篇论文则是认为库蒙通过强行资料来符合他预先确定的琐罗亚斯德教的起源模式,因而严重扭曲了可以得到的证据。戈登这么认为着波斯起源的理论是全然地无效的并且密特拉密教的起源在西方是一个完全新的创建。[191]

路德·H. 马丁(Luther H. Martin)也表达了类似的观点:“除了神明祂自己的名号以外,换句话说,密特拉教似乎已经在很大的程度上得到了发展,因此,从罗马文化的背景下可以得到最好的理解。”[192]

不过,根据霍普费(Hopfe)所述,“所有密特拉教起源的理论都承认了一种联系,可是却模糊的,联系到古代雅利安宗教的密特拉/密多罗神祇。”[26]在第二届国际密特拉密教学术研究大会报告,该会于1975年召开,乌戈·比安奇(Ugo Bianchi)说道虽然他欢迎“历史上倾向于质疑东方与西方之间密特拉教的联系”,但是“不应该意味着抹杀掉罗马人自己所清楚的是什么,就是密特拉斯是一尊‘波斯的’(更广泛的观点是:一尊印度 - 伊朗的)神明。”[193]

博伊斯陈述道“尚未举出令人满意的证据来表明著,在琐罗亚斯德之前,在伊朗民族之间存在着至高无上神明的概念,或者是在他们密特拉之间──或者是其他任何的神灵──若不是在他们的古代(期间)就是在他们的琐罗亚斯德教万神殿之外曾经拥有了他或她自己(至高无上神明)的独立信仰。”[194]不过,她还表示道尽管最近的研究尽量减少了波斯宗教不自然的伊朗面貌“至少是在罗马帝国统治下所获得的形式”,而密特拉斯的名号就足以表明了“就这个面貌而言是非常重要的”。她亦有说道“在最早的文献参考中已承认了这秘密宗教的波斯联系关系。”。[32]

贝克则告诉着我们说自从1970年代以来学者们普遍摈拒了库蒙(的理论),但补充的说最近关于琐罗亚斯德教徒在公元前期间是怎么样的理论现在使得库蒙的东-西传递的一些新形式成为了可能。[195]他如此说道:

译文:“…一项波斯人在秘密宗教中不可磨灭事物的残留以及更好地理解什么是构成实际的拜火教拥有允许现代学者们去假设关于罗马的密特拉教乃延续著伊朗的神学。这个的确是密特拉密教学术研究的主线。库蒙式模型其乃为随后的学者接受、修改,或者是驳斥。为了将伊朗的教义从东向西传播出去,库蒙假设了一个似是而非的,若是假设的,其中间的媒介为:在安纳托利亚境内散居的伊朗(波斯)法师。更有问题的是──及其从来没有被库蒙或他的继承者妥善地解决──真实生活中的罗马密特拉教徒是如何在西洋外观背后接着主张著一个相当复杂和精致的伊朗神学。除了两个位在杜拉的‘祆教法师’圣像连同一起的卷轴之外,这些教义的载体没有直接和明确的证据。…在一定程度上,库蒙的伊朗范式,尤其是在图尔坎的修改形式中,当然是貌似有理的。”[196][197][198] 原文:"... an indubitable residuum of things Persian in the Mysteries and a better knowledge of what constituted actual Mazdaism have allowed modern scholars to postulate for Roman Mithraism a continuing Iranian theology. This indeed is the main line of Mithraic scholarship, the Cumontian model which subsequent scholars accept, modify, or reject. For the transmission of Iranian doctrine from East to West, Cumont postulated a plausible, if hypothetical, intermediary: the Magusaeans of the Iranian diaspora in Anatolia. More problematic – and never properly addressed by Cumont or his successors – is how real-life Roman Mithraists subsequently maintained a quite complex and sophisticated Iranian theology behind an occidental facade. Other than the images at Dura of the two ‘magi’ with scrolls, there is no direct and explicit evidence for the carriers of such doctrines. ... Up to a point, Cumont’s Iranian paradigm, especially in Turcan’s modified form, is certainly plausible."

他还如此地说道“旧有的库蒙式模型有关形成是在,以及扩散是从,这安纳托利亚…即决不是绝对地-也不应该是如此。”[199]

贝克推论说这支信仰是创设于罗马的,其由具有希腊和东方宗教学问的单一创始人(所成立新兴的罗马信仰),但也联想到某些概念习惯于采取了可能是(波斯)已经通过了希腊化的王国(传入欧洲的路径)。他评述说“密特拉斯-此外,被视为与希腊太阳神赫利俄斯等同的密特拉斯”是位在内姆鲁特地带于融合了希腊-亚美尼亚(Armenian)-伊朗之间皇家信仰的(合一)神明,乃是由科马基尼王国的安条克一世于公元前一世纪中叶所创立的。[200]在提出理论的同时,贝克亦言之他的方案很有可能被认为是库蒙式(理论)的两种途径。首先,因为它再次注意到了安纳托利亚和安纳托利亚民族(这项因素),并且更重要的是,因为它回到了库蒙首先使用的方法论。[201]

默克尔巴赫提议道祂(密特拉斯)的秘密宗教实质上是由特定的人士或者是人群所创造的[202]并且在特定的地方创建,即罗马市,由来自(罗马帝国的)东部行省或者是国家边界的人(法师、贤者、波斯僧侣),他详细了解有关伊朗神话的内容,也因此他便编制成他的新兴启蒙等级制;但在那方面而言他一定是希腊人或者是懂得希腊语文的人因为他将希腊柏拉图主义的要素与之结合地融入其中了。这个神话,他是这么认为的,大概是创建在帝国官僚体系的环境下,以及其成员身上所制定出来的。[203]克劳斯倾向于同意(这项说法)。贝克称这个为“最有可能的情景”并且表示说“直到现在,密特拉教一般都被视为仿佛是以某种方式从伊朗的初期形式演变成了如同托普西般的-一旦这观点被明确地说明后这即是一个最不可信的情景。”。[204]

考古学家刘易斯·M. 霍普费(Lewis M. Hopfe)指出了罗马帝国的叙利亚行省仅仅只有三座的密特拉寺而已,与相距更远地西方而言情况则是相反的。他写道:“考古学表明著罗马密特拉教派在罗马有其中心…这被称之为密特拉教的完全发达宗教似乎已经在罗马境内开创并且被士兵和商人带到了叙利亚去。”。[1]

从现代其他学者所持有的不同观点来看,乌兰西主张著密特拉秘密宗教开始于希腊罗马世界作为宗教对于由希腊天文学家喜帕恰斯的昼夜平分点的岁差之天文现象所发现的反映-那样的一个发现是相当于发现整个宇宙以前所未有的方式在移动着。这个新的宇宙运动,他提出了,是被密特拉教的创始人给看出来了作为表明存在着一尊能够去转移这宇宙范围以及从而治理著天地万物的新兴且强而有力的神明。[205]

然而,阿德里安·大卫·休·比瓦尔或简称A. D. H. 比瓦尔(Adrian David Hugh Bivar or A. D. H. Bivar)、L. A. 坎贝尔(L. A. Campbell)以及G. 维登格伦(G. Widengren)则不同地认为着罗马密特拉教意味了某种形式的伊朗密特拉崇拜之延续。[206]

根据安东尼娅·的黎波里(Antonia Tripolitis)所述,罗马密特拉教起源于吠陀时代的印度并且这教派在其遇到向西方传布的旅程中这教派便搜罗许多文化的特征了。[207]

迈克尔·斯佩德尔(Michael Speidel),他是主修军事史的,将密特拉斯与太阳神的英雄欧里昂联系在一起。[208]

在罗马帝国境内这支秘密宗教最初的重要发展似乎发生得很快,在安敦宁·毕尤君主执政的晚期以及在马可·奥里略的统治保护之下。到了此时这支秘密宗教所有的关键要素都已经到位了。[209]

密特拉教在西元二世纪与西元三世纪的期间达到了其受欢迎程度的最高点,当索尔·无敌者的崇拜被纳入了国家-发起的信仰之同一个时期中该教派即以“惊人”的速度在传播着。[210]在这个期间肯定的是帕拉斯有专门为密特拉斯写了一本专著,而稍后的欧布洛斯便写了一部《密特拉斯的历史》(History of Mithras),虽然这两件作品现在都佚失了。[211]根据四世纪的《罗马帝王纪》所载,(罗马)皇帝康茂德加入了祂(密特拉斯)的秘密宗教[212]但这支教派从未成为国家信仰之一。[213]

历史学家雅各布·伯克哈特写道:

译文:密特拉斯是灵魂的引导乃因他从俗世的生命之中深入引导著那一个他们对于光明已经堕落倒退(的灵魂)那光明正是从他们所散发出来的…其不仅仅是来自于东方和埃及人的宗教以及智慧,更不用说是基督教的,在尘世上的生命只是要过渡到更高生命的概念是由罗马人所导源的。他们自己的痛苦和衰老的意识使得其足以明白的那是尘世上所有的生存是艰苦和痛苦的。密特拉斯-崇拜成为了一个,而且也许是最重大意义的,有关在衰落的异教之中的救赎宗教。[214] 原文:Mithras is the guide of souls which he leads from the earthly life into which they had fallen back up to the light from which they issued ... It was not only from the religions and the wisdom of Orientals and Egyptians, even less from Christianity, that the notion that life on earth was merely a transition to a higher life was derived by the Romans. Their own anguish and the awareness of senescence made it plain enough that earthly existence was all hardship and bitterness. Mithras-worship became one, and perhaps the most significant, of the religions of redemption in declining paganism.

当密特拉斯的信仰走向结束时其就很难以再追诉到底了。贝克表示说“在〔第四〕世纪的很早期遍及整个帝国这宗教就像死了一样。”。[215]出自于西元四世纪的碑铭是很少的。克劳斯表示说碑铭显示出密特拉斯由罗马元老们列在碑铭上作为信仰之一他们(罗马元老们)没有转变为基督教,(乃是以)作为在上层集团之中“异教复兴(pagan revival)”(身份)的一部分。[216]乌兰西认为着“密特拉教的衰落伴随着随着基督教权力的上升,直到五世纪初,当基督教成为强大到足以借由迫使宗教对手像是密特拉教令其灭绝时。”。[217]根据迈克尔·施派德尔(Michael Speidel)所述,基督徒与这个忌惮的敌人一起激烈的争夺并在西元四世纪期间压制了祂。一些密特拉密教圣所被摧毁加上宗教不再是个人选择的事项了。[218]根据路德·H. 马丁所述,在西元四世纪的最后十年期间罗马密特拉教走向结束是随同基督教皇帝狄奥多西的反异教法令颁布(而画上了句点)。[219]另外,基督教对于西洋文明的道德价值观之建立以及传统礼节之规范是有其伟大的贡献存在;而密特拉教虽属秘密宗教,本质上与基督教同样是以救赎人类为宗旨的,两个宗教之间各有属于自己的特色在当时的西方都是优秀杰出的宗教。

在教堂的底下已发现的一些密特拉寺的座落处,举例来说即圣塔普利斯卡密特拉寺以及圣克莱门特(San Clemente)密特拉寺,教堂在地基上方的规划某种程度上被制造成基督教统治著密特拉教的象征。[220]根据马克·汉弗莱斯(Mark Humphries)所述,在某些地区刻意的隐藏了密特拉密教崇拜的物品意味着正在对基督徒的攻击采取预防措施。然而,在好比莱茵河边界这样的地区,纯粹的宗教考虑不能解释密特拉教的结束,而蛮族的入侵也可能发挥了作用。[221]

实际上没有证据来表明密特拉斯的信仰延续到了西元五世纪。尤其是,在比利时高卢境内位于庞斯·萨拉米(Pons Sarravi,今日名之萨尔堡〔Sarrebourg (Saarburg)〕)的密特拉寺已经回收了大量由信徒们存放奉献的硬币,那一系列的硬币是从加里恩努斯(Gallienus,253~268)到狄奥多西一世(379年~395年)在位期间所施行的。当密特拉寺被摧毁时这些硬币散落在地板上,因为基督徒无疑地看待这硬币是污染的,并因此为密特拉寺的活动提供可靠的日期。[222]在西元五世纪中任何一座密特拉寺持续的运作是不能表明的。所有密特拉寺的一系列硬币最后在西元四世纪末结束(施行了)。这支信仰是早于伊西斯崇拜而消亡的。伊西斯在中世纪期间仍然被当时的人们记得为古埃及宗教的神灵,但是密特拉斯在古代晚期已经被人们所遗忘了。[223]

弗朗茨·库蒙在他的书中陈述著密特拉教可能幸存在今日瑞士阿尔卑斯山脉一些偏远的州以及今日法国的孚日省(Vosges,因孚日山脉而得名)境内而直到西元五世纪。[224]

《约翰,内廷宫务大臣》(John, the Lord Chamberlain),历史推理长篇小说系列描绘了一个仍然活跃于查士丁尼宫庭的密特拉教徒团体,但是却没有历史证据表明关于这支宗教教派的晚期幸存教徒。

屠牛意义

根据库蒙所述,屠牛像的雕塑是一种希腊罗马的有关于琐罗亚斯德教对宇宙起源事件之阐释的表示法,此事件即是描述于西元九世纪在琐罗亚斯德教的经文《创世纪》(Bundahis、Bundahishn)之中的内容。在这个经文之中邪灵阿里曼(不是密特拉)诛戮原始生物盖维福迭达(Gavaevodata),这原始生物被表示为牛。[225]库蒙的想法是诛戮了牛,在这一个神话版本之中密特拉斯是应该存在的,而不是阿里曼。但根据亨尼尔斯所述,没有这样已知的神话变体,而且这仅仅只是个推测:“没有已知的伊朗经文之中〔若非琐罗亚斯德教的或者是其他教派的〕记载着密特拉屠杀公牛。”。[226]

大卫·乌兰西从密特拉寺本身发现到了天文学的证据。[227]他提醒着我们柏拉图主义的作家波菲利在西元三世纪时写道像洞穴般的神庙密特拉寺描绘了“一个世界的形像”[228]而且琐罗亚斯德奉献了一个类似于密特拉斯所制造的世界之洞穴。[167]凯撒利亚·马力提马密特拉寺的天花板保留了蓝色颜料痕迹,这可能意味着天花板被画成描绘着天空和星星。[229]

贝克已经提供了以下关于屠牛像的天体解析:[230]

有关于密特拉斯屠牛像(Tauroctonous Mithras,以下简称TM)其本身已经被学者们提出了几个天体的特性。贝克将这些天体特性总结于下表之中。[231]

| 学者 | 判定 |

|---|---|

| 包萨尼,A.(Bausani, A.,1979年) | TM是与狮子座相关联,因为这屠牛像是一种古老狮子-公牛(狮子座-金牛座)争斗主题的类型。 |

| 贝克,R. L.(Beck, R. L.,1994年) | TM = 太阳进入狮子座。 |

| 因斯勒尔,S.(Insler, S.,1978年) | 屠杀公牛 = 金牛座的偕日设定。 |

| 雅各布斯,B.(Jacobs, B.1999年) | 屠杀公牛 = 金牛座的偕日设定。 |

| 诺斯,J. D.(North, J. D.,1990年) | TM = 参宿四(猎户座α)设定,祂的刀 = 三角座设定,祂的披风 = 五车二(御夫座α)设定。 |

| 罗格斯,A. J.(Rutgers, A. J.,1970年) | TM = 太阳,公牛 = 月亮。 |

| 桑德林,K.-G.(Sandelin, K.-G.,1988年) | TM = 御夫座 |

| 施派德尔,M. P.(Speidel, M. P.,1980年) | TM = 猎户座(太阳神阿波罗的英雄欧里昂)。 |

| 乌兰西,D.(Ulansey, D.,1989年) | TM = 玻耳修斯。 |

| 魏斯,M.(Weiss, M.,1994年、1998年) | TM = 夜空。 |

乌兰西已经提出了密特拉斯似乎是来源于英仙座星群的说法,祂的方位恰恰好是位于夜空的金牛座之上。他(乌兰西)看到了这两尊神话人物之间(神祇密特拉斯与英雄玻耳修斯)在肖像学以及神话学对比之下的相似之处:两位皆为年轻的英雄,携带一把匕首,并且佩戴着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽。他还谈到了玻耳修斯诛杀戈耳工以及屠牛像形像的相似性,两位神话人物正好都有与地下洞穴相关联(的神话背景)并且随着进一步的证据显示出两者皆与波斯有联系。[232]

迈克·施派德尔将密特拉斯与猎户座星群联系在一起乃是因为临近金牛座的关系,而且这尊神话人物描述的一致性质为拥有宽阔的肩膀、衣服的下摆是漏斗状的,以及在腰部上用腰带系紧,从而呈现了星座的形态。[208]

贝克指责了施派德尔与乌兰西采取关于一种字面的制图逻辑,将他们的理论描述为一种“使人迷惑的”的论点其乃是“诱骗他们落入一个虚假的线索”。[233]他是认为着这屠牛像作为一种星宿图表的字面解读引起了两个主要问题:它是很难去找到关于密特拉斯祂本身相对应的星座(尽管由施派德尔和乌兰西所下足了功夫与努力)而且,不同于星宿图表,屠牛像的每个特征可能不仅仅是一个单一的对应角色。而不是将密特拉斯视为星座,贝克是认为着密特拉斯是在天体舞台上的主要旅者(由场景的其他符号意味着),无敌的太阳移动通过星座。[233]不过话又说回来,迈耶认为着这密特拉斯圣仪反映了密特拉教的世界还有也许可以证实对于乌兰西的密特拉斯学说是被认为应该对关于岁差负责任。[234]

最新文物

1996年~1997年在叙利亚境内的哈瓦蒂发现了一座密特拉寺,是位在荒废的教堂下方,当教堂地板的一部分崩塌时而让这座密特拉寺显露出来。该房间是由灿烂精彩的画作赋予了特色。这座密特拉寺在罗马帝国任何地方似乎呈现出在使用上是年代最晚的庙堂之一。这座神庙的一个好奇的特点是在12月25日。一道光线照射在里面,落在应该是站立姿态的崇拜神像壁龛上。[235]

该地的座标:35° 25' 05" N,36° 23' 53" E/35.418° N,36.398° E。[236]

哈瓦蒂村位于阿帕梅亚以北15公里处。一座重要的教堂复合体在1970年代被挖掘出来。这教堂由阿帕梅亚大主教圣弗蒂乌斯建造于公元480年代并且铺上镶嵌艺术。这教堂是一座早期教会的重建,也是与镶嵌艺术一起重建的,是建造于西元四世纪末。而这镶嵌艺术现已被迁移到博物馆之中珍藏。在1996年~1997年的冬季期间,教堂地板的一部分崩塌,露出一间房间,这间房间被盗贼所挖掘,他们拆除了一幅画。他们还发现到了一个有绘画的天花板,但是这个天花板被证明是不可能被拆除走的。叙利亚当局迅速逮捕了盗贼,并且这幅画现在被珍藏在大马士革的博物馆里面。一位荷兰考古学家于1997年9月拜访了该地并且拍摄了他能看到的内容。1998年8月由M. 加夫利科夫斯基(M. Gawlikowski)领导的波兰考古学家团队被指派开始挖掘工作。他们发现这幅画是在该年的9月在东部墙垣上所看到的。1997年经由曝光与掠夺而已经消失不见了。叙利亚当局决定就地的保留现场并且使公众可以方便拜访该处。这个考虑是要保证进一步的工作(考古以及史学)活动期。[237]

这座密特拉寺的主室宽4.80米,为东西两侧。其西墙长6.45米,以及东墙7.20米,为南北两侧纵深。这东墙是天然洞穴的原始岩墙。

没有左边的长椅。右边的长椅的走向是朝着房间的南边进而沿着南边的角落走。

在北墙中间有一个壁龛,宽3838米并且高出在房间的地板上。这一定包含了屠牛像的浮雕,屠牛像尚未被发现但可能是在未被挖掘的地区。讲台是设立在屠牛像之前,并且后来在讲台的右手边被加了一个小台座,伴随着两个台阶通向它。在讲台前方,而且朝向右边,设立着一座祭坛,其被发现时已经横躺地倒在地上了。

中央的居室面积(floor-space)稍微凹进。下面似乎有一个凹陷的空间,还有一个小开口通向里面,大概是排水渠。在房间内部建造了8层大石块的墙壁,以支持其上方的教堂,此墙高出约3.5米。这道墙已被挖土机所拆除了。[238]

墙壁和壁龛都污损了,还有画作也是同样的情况。在某几处发现高达六层的画作。最后两层绘画越过讲台和台座,并且年代是可以确定的,借由在讲台前面替代的台阶,年代不会早于约公元360年。

在使用的最后阶段,整个北面、西面与东面墙壁都有被上以绘画,以及壁龛前面的建筑结构也有。在地板上发现了两层小洞穴。 在下层小洞穴发现了戴克里先的硬币,可能显示了密特拉寺的建立日期。在上层小洞穴也发现了一些硬币,年代全部都是西元四世纪的,还有年代最晚之一的阿卡狄奥斯(公元383年以前)。属于同期的灯具和陶器也有被发现到。从这可以推断著这座密特拉寺直到西元四世纪的最后几年,当这庙堂被圮毁还有建立在其上的教堂之前,仍然还在使用之中的。由于可确定最晚年代的密特拉密教宗教遗迹是出自于公元387年的罗马碑铭,还有西顿的文物可能是公元389年,这表明著哈瓦蒂密特拉寺是已知道年代使用最晚的一座密特拉寺。[239]

在地板上都有发现了各种各样的石祭坛,都被推倒了。在西墙中间有一扇门可即进入前厅。

而前厅的入口处则是位于前厅的南边。

主室西墙有一道水平的缝隙,是向前厅的方向看去。实验显示著光通过这道缝隙的出处照射到壁龛上,而且特别的是整个12月直到1月6日光会照耀在密特拉斯圣像的圣颜上(如果正常比例的屠牛像浮雕存在于此壁龛的话)。[240]

主厅和前厅两处在人们可以看到的所有墙壁之上都被丰富地画上宗教绘画。

包含人物的绘画带是110厘米高,在其上方到天花板有一个宽的红色带。在这下方则是几何图案的护墙板墙裙(dado),这也涵盖了讲台。

于壁龛右侧的场景描绘,从这一侧的最左边开始略述:

一、宙斯与巨人族之间的战斗。这尊神的绘画保存比较不完整,但仍可看到但穿戴着披风和靴子。两只怪物在祂的两侧,裸体的,人类双腿的末端被蛇盘曲在其上。画像的头已经不见了。

二、一尊胜利的宙斯被显示在洞穴的东北角,于宙斯与巨人族之间的战斗的右边,坐在宝座里面一个圆形的花圈上。

三、在东侧的墙上,其接下来,是密特拉斯被描绘为一位从岩石中诞生的年轻人,祂被一条庞大的蛇给围绕盘曲著。祂被描绘为裸体但是祂的手上握着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽。

四、一位裸体男孩在柏树之中,又伴随着一顶弗里吉亚无边便帽。

五、一尊巨大身材且衣冠楚楚的太阳神,连同举起了双手。

六、更进一步地沿着东侧墙壁,这些画作几乎完全消失了。一个碎片可能意味着正是由密特拉斯所携带的公牛画像上面掉下来的。

加夫利科夫斯基提出著这样的看法是这一系列可能是有意为了将密特拉斯同其他的神明──也就是说,阿波罗、阿提斯(Attis)以及索尔──来做出辨认。

于壁龛左侧的场景描绘,从这一侧的最右边开始略述:

一、一道有拱门的城墙。在墙的顶部,有一排狰狞丑恶和可怕吓人的头颅,带有毛茸茸的头发以及被磨碎的牙齿。每一个都被一条黄色长线所打伤,显然是一缕光的射线。其中一个头颅业已掉落到了门外的地面上了。

二、一名穿戴富裕的男子贴近的站在一只巨马旁边,在此人脚上伴随一只用铁练锁住的恶魔。

三、另一位人物(画像已模糊了)。

在房间的西南角是一个狩猎场景。

在南边的墙壁是保存不良壁画的碎片,显示出一匹马向右移动还有三组波斯发型,也许表示著在一条路线上前进的骑士。

这些人物的眼睛已经被刮伤了,大概是由建造教堂的石匠所造成的。[g]

天花板画是对称的并且有一个精巧的框架。里面是一篮的葡萄在两侧有两只鸟(可能是孔雀?)和两碟盘子。在早期的绘画层上应该会有一幅密特拉斯的圣像,因为在连同祂大希腊字母名号一起的石膏碎片被重新找回了。

在恶魔的描绘下面没有长椅的设置。在右边的长椅有被找到。最后的仪式还有剩下一些膳食残余,由鸡肉和猪肉所构成的。几盏灯具和灯具碎片,材质是以陶器和玻璃制成,年代约为西元四世纪到西元五世纪,也有被发现到。

在北边的墙壁上是两只狮子的场景,彼此对峙的,撕裂了黑色人类形像。狮子身体保存不完整。相对的人的下半身保存得更好,穿着一条短裙,有红色、有绿色。第三位黑人的嘴巴上显示出流淌著血液,但他的裙子没有保存下来。

在东边的墙壁上,门口的北边,有更进一步的壁画。右边画有一只巨大的白马,它的其中一只前腿抬起,蹄的部分隐藏着一座四脚架或祭坛,一条蛇围绕盘曲起来。在马前面有伫立着一名雄伟的男性人物从他的腰部的绘画还有保留下来。他穿着红色长袍到达膝盖,在前面的装饰在两排垂直的珍珠之间带有镶边的宝石。长袍越过了他的裤子,这条长袍穿过他的裤子,其中每条腿也是同样地编织着两排垂直的珍珠之间带有镶边的宝石。然而,这幅壁画最引人注目的特点是,那个可怜的同伴被英雄人般的物用链子锁在一起了。链子是两条的,长度是从骑士的手到达黑人的每个手腕,这黑人从背面来看他完全是赤身裸体的,采蹲伏的姿势。这位人物绘画整体保存完好,所以非常清楚的是其形象除了正常的身体之外他有两个明显不同的头,转向相对的侧面并且在颈部戴着金属项圈。

与密特拉寺相关联的物品被重新找回的很少。只有其中的几个奉献祭坛有被刻写上文字存在着,显然地年代是在西元二世纪期间。祭坛上具有一个马库斯·隆吉努斯(Marcus Longinus)的名字,乃是以希腊文所刻写的。

还有神像的脚可能属于狮头神灵的。

其他的神明

这支密特拉斯的信仰教派在罗马帝国境内的宗教之中具有融合性质的一部分。几乎所有的密特拉寺都包含着专门献给其他信仰的神明之神像,并且在其他的圣所之中找到专门献给密特拉斯的碑铭这也是很常见到的情形,尤其是在朱庇特·多立克努斯的那些圣所更是如此。[241]密特拉教对于罗马的其他传统宗教而言并不是非传统的,而是宗教习俗的许多形式之一,还有也能够发现到许多密特拉密教的入教者参与了罗马公民的宗教活动,并且他们(密特拉密教的入教者)还可以作其他秘密宗教信仰崇拜的入教者。[242]

密特拉斯有时候会以类似于俄耳甫斯教的神灵法涅斯的方式来描绘。

在俄耳甫斯教之中,这尊神灵法涅斯[243]在最初一开始就从宇宙蛋(World-Egg or Cosmic egg)或者是奥菲斯蛋中诞生出来,因而创造出了宇宙天地。有证据表明著关于这项俄耳甫斯教的教义有时影响了密特拉斯的崇拜。[244]

有一些文献证据连接了密特拉斯和法涅斯,或者是祂们神格的互换。一份出现在柴乐诺波以及士麦那(位于土耳其西部港市伊兹密尔)的席恩(Theon)有关于宇宙创造八元素的目录之中;大多数元素都是一样的,但是在柴乐诺波手中的那份目录第七个元素是‘密特拉斯’,在席恩手中的那一份则是为‘法涅斯’。[245]

这两份目录是从罗马的希腊碑铭所显示出来的是能够被确认的史料,即CIMRM 475号,这碑铭乃是由一位“教父”与祭司奉献给予宙斯-赫利俄斯-密特拉斯-法涅斯(Zeus-Helios-Mithras-Phanes)。[246][247]

CIMRM 860号,出自于维科维恩/波柯维西恩(Vercovium / Borcovecium,豪塞斯特兹)在哈德良长城上的浮雕显示出一尊神灵手握匕首与火焰并且从宇宙蛋之中诞生,都是同样表现为黄道环(在周围)的形状。[248]这件宗教历史文物是在豪塞斯特兹的密特拉密教洞穴中所发现到的,在两座奉献予密特拉斯的祭坛之间,并且在主要信仰浮雕的前方。[249]

CIMRM 985号,是一件类似的浮雕,于1928年被发现在特里尔的密特拉寺里面,一样是在两座祭坛之间,一座是属于密特拉斯的以及另一座是属于索尔的,并且又可能有主要信仰的浮雕在其后方。这浮雕描绘了密特拉斯从岩石内的一轮黄道带中之宇宙诞生。密特拉斯一只手正在握着世界之球,另一只手则伸出来摸触著黄道带。[250]

这些与在意大利摩德纳境内埃斯泰画廊(the Galleria Estense,或译为:埃斯特美术馆)里的浮雕有相似之处,最初是来自于穆蒂纳(Mutina,现名摩德纳)或者是罗马,在许多相同的背景下这浮雕所显示的神祇是法涅斯而不是密特拉斯。[251]这显示了法涅斯源自于一颗蛋(宇宙蛋、世界蛋)连同在祂的双脚附近有火焰喷发而出,在法涅斯的外围被黄道十二星座所环绕着,图像与位在纽卡斯尔的相关图像是非常的相似。[252]

乌兰西已经解说了在密特拉斯、法涅斯、艾翁,以及狮首神祂们之间的各种相似之处,其中还包括了摩德纳的浮雕、原来的俄耳甫斯教,进入到了密特拉斯的入教者手中,这是根据着一份上面已有刮伤的碑铭之记述。[253]

密特拉斯在碑铭之中素来被描绘成“sol invictus(索尔·无敌者)”(无敌的太阳)。[254]但是索尔和密特拉斯是不同的神灵。[255]invictus(无敌者)这个词的模糊暧昧之处意味着祂被用来当作许多神灵的头衔。[256]密特拉教从来没有成为国家性的信仰,然而,也不像罗马官方晚期的索尔·无敌者信仰。[257]

尽管密特拉斯祂自己被人们称呼为索尔·无敌者,“无敌的太阳”,不过祂和索尔还是有以作为独立的身份出现在几个场景之中,以关于宴会场景而言正是最突出的例子。于其他场景的特点则是密特拉斯攀登到索尔的战车后方上、神灵们握着手以及两尊神明在一座祭坛上连带着一大块肉在考托佩斯使用商神杖喷出火舌或者是爆出火花的上方。 一个特殊的场景显示出索尔在密特拉斯的面前屈膝,密特拉斯握着一个物体,祂手中的东西,被解读为若不是波斯帽就是公牛的腰腿。[258]

朱庇特·多立克努斯,乃为罗马秘密宗教信仰的神明,起初是赫梯-胡里安(Hittite-Hurrian)当地的丰饶之神,以及位在多立克(Doliche)城(就是现代在土耳其境内东南方的大加济安泰普市内悉嘎米〔Şehitkamil〕区的一个村庄──杜鲁克〔Dülük〕)的雷霆崇拜。后来这尊神灵被赋予了闪米特族的性格,但是,在阿契美尼德王朝的统治(公元前六世纪到公元前四世纪)之下,祂被认为与波斯主神阿胡拉·马兹达等同,从而成为宇宙之神。通过了希腊人的影响后,祂为宙斯·奥罗马斯德斯(Zeus Oromasdes);并且在这称号之下,祂是与波斯的另一尊神灵密特拉的信仰密切相关。朱庇特·多立克努斯及其配偶的崇拜逐渐向西被带进了罗马以及其他军事中心,后来在西元二世纪与西元三世纪期间,这支教派变得非常受欢迎。在罗马秘密宗教之中,祂不仅被公认为是天上神明,而且被认为是具备着控制军事成功和安全的职掌。祂通常的宗教形象表现是站在一头公牛之上并且携带祂的特殊武器,及双斧与闪电。

而密特拉斯与朱庇特·多立克努斯的信仰的关系,可以从考古学上位于卡农顿的密特拉寺所拥有的建筑构造看来像是与当代的朱庇特·多立克努斯神庙有密切相连。[259]另外有两座密特拉寺是被发现于科马基尼王国本身的多立克城。该相关书面资料的出版者提出了追溯到西元一世纪的年代,但是一般来说追溯到西元二到三世纪的年代才是优先选用的历史时期,并且这两座(密特拉斯的)神庙是与莱茵河边界的密特拉寺有关。[260]

早期的基督教护教士指出了密特拉密教和基督教仪式之间的相似之处,但依然对密特拉教采取了非常消极的观点:他们将密特拉密教仪式解读为基督教仪式的邪恶副本。[261][262][h]譬如,特土良写道作为密特拉密教启蒙礼仪的序幕,这入教者及在礼仪结束之时便给予沐浴的仪式,会在额头上获得一个被承认的印记。他描述这些仪式为一种恶魔所假冒的基督徒之洗礼以及搽圣油(chrismation)。[263]特土良与许多教父不同,他从来没有被东方或西方普世的传统教会认定为圣人,因为他对诸如圣子和圣灵到圣父的明确从属关系等问题的教诲,[264][265]以及他谴责寡妇再婚和逃离迫害,与这些传统的教义相抵触。但是可以确定的一点是他因理论贡献被誉为拉丁教父和西方基督教神学鼻祖之一。早期的基督教与密特拉斯的崇拜之间关联的概念是基于西元二世纪的基督教作家殉教者·游斯丁的一份评注而来,他指责了密特拉斯的入教者冒充基督教圣餐仪式。[266]殉教者·游斯丁还将密特拉密教启蒙领圣礼与(基督教的)圣餐礼一起做了个比较:[267]

译文:因此在这密特拉斯的秘密宗教里面模仿中的邪恶之魔鬼也已经流传了应该执行的同样事情。对于那些面包和一只水杯于这些秘密宗教中陈设在这入教者连同著一定的演说你可以知道或者可以学习之前。[268] 原文:Wherefore also the evil demons in mimicry have handed down that the same thing should be done in the Mysteries of Mithras. For that bread and a cup of water are in these mysteries set before the initiate with certain speeches you either know or can learn.

基于此,欧内斯特·勒南在1882年时提出了,在不同的情况下,密特拉教可能已经跃升到了现代基督教的重要地位。勒南对两个对立的宗教信仰进行了生动描述因而写道:“如果基督教的发展被某些致命的弊病给抑制了,世界将会是密特拉密教的…”[269][270]不过在勒南执笔撰写的时候,在库蒙收集史料之前,很少有人知道关于密特拉斯(的崇拜)。[271][272]然而,这个理论从此就有所争议了。列奥那多·鲍伊(Leonard Boyle)他在1987年写道:“太多了…已经成了密特拉教对于基督教的‘威胁’,”[273]指出了在整个罗马市不过是有五十座已知的密特拉寺。J. 阿尔瓦·埃斯克拉(J. Alvar Ezquerra)认为着由于这两个宗教没有同样相似的宗旨,事实上两个宗教团体的宗旨是不同的,于此密特拉教从来没有接管罗马世界的真正威胁。还有密特拉斯信仰没有普及任务上的意图,甚至在其受欢迎程度的高峰期也没有过。[274]

根据玛丽·博伊斯所述,对于位在西方的基督教而言密特拉教是个强而有力的敌人,虽说她对在东方持有怀疑态度。[275][276][277]菲利波·夸雷利(Filippo Coarelli,在1979年的时候)已把四十个实际或可能的列成表并估计著罗马将有“不少于680~690座(not less than 680–690)”的密特拉寺。[7]刘易斯·M. 霍普费声明著多于400处的密特拉密教遗址已被发现。这些遗址遍布了整个罗马帝国地点从远在位于东边的杜拉·欧罗普斯,以及直到西边的英格兰都有。他,连带的,那么说了密特拉教可能是基督教的对手。[10]大卫·乌兰西认为勒南的言论“有些夸张”,[278]除了将密特拉教视为“罗马帝国境内基督教的主要竞争对手之一”之外。[278]乌兰西注意到了对于理解“基督教信仰到诞生其文化的基体(the cultural matrix out of which the Christian religion came to birth)”密特拉教的研究同样是非常重要的。[278]

没有任何方向的证据来表明在密特拉斯的崇拜和早期基督教之间有直接的影响。[279]更准确地说这样的类似性既然会存在是归因于两者出现在共同的环境。

在西元二世纪的哲学家克理索(Celsus)提供了一些证据来证明了奥菲特·诺斯替(Ophite gnostic)教义思想影响了密特拉斯的秘密宗教。[280]

在较古老的学术文献之中基督教与密特拉斯的崇拜之间出现了许多应该的相似之处。一般来说这些都是基于推测,或者是起于试图通过观察基督教思想而对密特拉斯的崇拜散发出了一些理解。

费尔马歇仁在1975年时写道相似之处来自于共同文化世界的存在。[281]除了这个相同因素之外,而不是(直接的)在任何一个方向上有看到借用的迹象,曼弗雷德·克劳斯也持相同的意见。[282]

一些极其猖獗的声称──那密特拉斯有着12位门徒、是一名流浪的导师、死亡与再次升天,等等。──在密特拉斯与耶稣之下作为替代的被讨论著。

库蒙陈述到了密特拉斯的诞生日是在12月25日,在举行太阳盛宴的基础上于这个日子中还有密特拉斯(的圣诞可能会一起庆祝),当然了,也都包括。这个想法只是猜测,但已被广泛接受。[283]克劳斯重复了这一说法。[284]但贝克表示说事实并非如此。事实上他称这个主张为“古老久远的‘事实’”。他接着说道:“事实上,唯一的证据就是在费罗卡鲁的历法上无敌者诞辰庆典的日期。‘无敌者’当然就是索尔·无敌者,(罗马皇帝)奥勒良的太阳神。其非遵循着一尊不同的、早期的,以及非官方的太阳神,索尔·无敌者·密特拉斯,是必然的或者甚至是可能的,也是在那天出生的。”[285]

但后来的克劳斯表示:“密特拉密教没有自己的公开仪式。natalis Invicti〔无敌的(太阳)诞生〕的节日,12月25日举行,是普遍性的太阳节日,并且绝非是特定于密特拉斯的秘密宗教。(the Mithraic Mysteries had no public ceremonies of its own. The festival of natalis Invicti [Birth of the Unconquerable (Sun)], held on 25 December, was a general festival of the Sun, and by no means specific to the Mysteries of Mithras.)”。[286]

史蒂芬·希曼斯(Steven Hijmans)已详细地论述了是否普遍性的“natalis Invicti(无敌的(太阳)诞生)”的节日与圣诞节有关但是没有说出密特拉斯作为一个可能来源的问题。[287]

于罗马境内在圣塔普利斯卡密特拉寺墙上一段严重损坏的描绘文字(CIMRM 485号,约公元200年)[288]可能包含以下言辞:et nos servasti (?) . . . sanguine fuso(英译为:and you have saved us ... in the shed blood;汉译为:而且你救了我们…在流淌著血之中)。这个意思是不清楚的,虽然大概是提及密特拉斯屠杀了公牛,因为没有其他来源言及到是密特拉密教救赎。servasti(救赎)已被视为确定的;但实际上只是一个推测,并且潘切里(Pancieri),乃是考察这个项目最近来的考古学家,他陈述道这应该是错的。[289]根据罗伯特·图尔坎所述,[290]密特拉密教救赎与个人灵魂的另一个世俗命运几乎没有(产生)关系,而是在人类参与了宇宙中善良创造反对邪恶力量著的斗争之琐罗亚斯德教模式。[291]

在多瑙河地区的宗教遗迹描绘了密特拉斯在火炬手的面前向岩石上射出弓箭,显然是要促进水喷将出来。[292]克劳斯陈述道,在膳食仪式之后,这提供了“与基督教显然是相似的”。[293]

有些学者表示说密特拉斯的入教者在前额上标有十字架的符号。这个想法被描述为(属于)一个学术上的神话。[294]

这个想法的基础是建立于特土良,他声明说密拉斯的追随者以非特定的方式在额头上被标记。[295]没有迹象表明这是一个十字架,或者是一个烙印,或者是纹身,或者是任何一种永久性的标记。[296]

出自于十八世纪末的一些作家已经认为着在中世纪的基督教艺术中的某些元素反映出了在密特拉密教里找到的形象。[297]弗朗茨·库蒙是其中之一,尽管他是在孤立地(元素)状况之下研究每一个主题而不是几个元素的结合以及他们是否在基督教艺术之中以相同的方式来相结合。[298]库蒙说明了在教会胜过异教之后,艺术家们继续采用着最初为密特拉斯设计的偶像形像以便来描绘着《圣经》中新的和陌生的故事。“工作坊的束缚”意味着第一批基督教艺术品在很大程度上以异教艺术为基础,以及“服装和姿势上的一些改变把异教的场景转换成了基督教的画面”。[299]

从此一系列的学者就密特拉密教的浮雕在中世纪罗马式艺术之中作了可能相之处的讨论。[300]费尔马歇仁表示说这种影响唯一确定的例子就是以利亚乘火马驾驶的战车上天空的形象。[301]德曼(Deman)陈述道比较孤立的元素是没有帮助的,而且应该研究结合(的元素)。他还指出了形象的相似性并不能告诉我们这样是否意味着意识形态的影响,或者仅仅是工艺的传统。然后他提供了一张对比密特拉密教图像的中世纪浮雕表单,但是谢绝从这张表单得出结论,因为这些将会是主观的。[302]

几座保存最完好的密特拉寺,这些密特拉寺尤其是在罗马境内像是位在圣克莱门特宗座圣殿(,而且位在圣塔普利斯卡,是现今在基督教教堂下面被发现的密特拉寺。在一些情况下教堂最初是建于西元五世纪荒废的、具崇高威望的建筑物顶端,并且其中一些曾经在地下室里含盖着密特拉寺。[303]

有证据表明著奥斯提亚境内密特拉寺的密特拉斯公共浴场可能在西元四世纪中叶被转换成教堂了。这年代是根据着建筑技术,以及字母Α(α,发音:alpha)和Ω(ω,发音:omega)的存在来做追溯的。[304]

在英国早期基督教教会的一项研究结论得出了那里的证据显示有倾向于避免将教堂定位在原先密特拉寺的遗址上。[305]

在十一世纪初的英格兰,于林肯境内的圣彼得在高斯(St.Peter-at-Gowts)教堂增建了一座塔楼,那里有一个非常饱受风化的浮雕被并入石工工程里,可能来自于罗马林肯一座未知的密特拉寺。祂被认为是狮首神的浮雕,通常描绘成带有着一双钥匙。有人认为着这种浮雕可能于十一世纪时被人们在其描绘圣彼得和他的两把钥匙的印像下重新的被使用着。[306]

相关条目

注释

参考文献

延伸阅读

外部链接

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.