Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Russian writer, publicist, poet and politician (1918–2008) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian writer. He was the winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in literature.[1]

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn | |

|---|---|

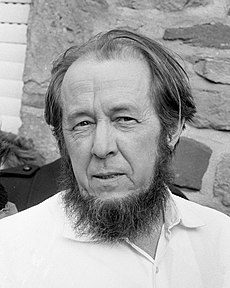

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in 1974 | |

| Born | Алекса́ндр Иса́евич Солжени́цын (Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn) 11 December 1918 Kislovodsk, RSFSR |

| Died | 3 August 2008 (aged 89) |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1970 Templeton Prize 1983 |

Solzhenitsyn was a novelist, dramatist, and historian. With his works, the Gulags, a network of Soviet labor camp (see forced labor), became well known. Due to this, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970, but also was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974. In 1994, Solzhenitsyn went back to Russia. After he died (of heart failure) he received a state funeral. He was very significant for revealing what life was like in the Soviet days.

During his imprisonment he left Marxism and converted to the Russian Orthodox Church.[2]

Best-known works

Much of Solzhenitsyn's work is autobiographical, based on things he saw and experienced in his own life. Solzhenitsyn was himself imprisoned in the Gulag for many years, and later was in a cancer ward (he recovered from the cancer).[source?]

After Khrushchev's Secret Speech in 1956 Solzhenitsyn was freed from exile and exonerated (cleared of all charges). The manuscript of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in edited form in 1962, with the explicit approval of Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev defended it at the Praesidium of the Politburo hearing on whether to allow its publishing, and added: "There's a Stalinist in each of you; there's even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil".[3]

Thus the lines between autobiography, reportage,[4] fiction and political observations are tied up together, more so than with most writers.[source?]

Poetry

- Prussian Nights (1974) (Russian: Прусские ночи)

Novels

- The First Circle (1968) A fuller version of the book was published in English in 2009.

- The title is an allusion to Dante's first circle of Hell in The Divine Comedy, where the philosophers of Greece, and other non-Christians, live in a walled green garden. They are unable to enter Heaven, as they were born before Christ, but enjoy a small space of relative freedom in the heart of Hell. The story is about prisoners (zeks) who are technicians or academics. They have been arrested under Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code in Joseph Stalin's purges after the Second World War.

- Cancer Ward (1968)

- The novel tells the story of a small group of cancer patients in Uzbekistan in 1955, in the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. It explores the moral responsibility – symbolized by the patients' malignant tumors – of those responsible for the suffering of their fellow citizens. During Stalin's Great Purge millions were killed, sent to labor camps, or exiled. Apart from officials who took the decisions, many more stood by and did nothing. They, too, were implicated. Others did worse: they denounced innocent people in order to gain advantages for themselves. The novel tells of how patients come to realise their part in these tragic events.

- August 1914 (1971)

- This is about Imperial Russia's defeat at the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia. The novel is an unusual blend of fiction narrative and historiography. It caused extensive and bitter controversy, both from the literary and the historical point of view. In 1984 a new version of the novel, much expanded, was published. By this time Solzhenitsyn had lived in the USA for some years. He was able to publish chapters previously suppressed, and new parts written after research at the library of the Hoover Institution. These included chapters on Vladimir Lenin which were published separately as Lenin in Zurich.

Short fiction

- The story is set in a Soviet labor camp in the 1950s, and describes a single day of an ordinary prisoner, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. The book's publication was an extraordinary event in Soviet literary history; never before had an account of Stalinist repression been openly distributed.

- For the Good of the Cause (1963)

- In a provincial town, the students of the local college help to build new college premises by doing most of the work themselves. When it is built, Soviet authorities order that the building should be handed over to a research institute; the students are told that this is "for the good of the cause". The story is an open criticism of the lack of democracy the prevailed at the time, and the lack of integrity of political leaders.

- Matryona's Place (1968)

- This is Solzhenitsyn's most read short story.[5] The narrator, a former prisoner of the gulag, longs to return to live in the Russian provinces. He takes a job at a school on a collective farm. Matryona offers him a place to live in her tiny, run-down home. They share a single room where they eat and sleep; the narrator sleeps on a camp-bed and Matryona near the stove. The narrator finds the farm workers' lives little different to those of the pre-revolutionary landlords and their serfs. Matryona works on the farm for little or no pay. Helping others one night, she is killed by a train. Her character has been described as "the only true Christian (and) the only true Communist" and her death symbolic of Russia's martyrdom.[6]

Non-fiction

- The Gulag Archipelago (three volumes, 1973–78)

- A history of the entire process of developing and administering a police state in the Soviet Union. It was circulated in samizdat (underground publication) form in the Soviet Union until its official publication in 1989. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Russian Federation, The Gulag Archipelago became required reading in Russian high schools.[7] The Arkhipelag GuLag (its Russian title), is both a rhyme and a metaphor used throughout the work. The word archipelago describes the system of labour camps spread across the huge Soviet Union as a vast chain of islands, known only to those who were fated to visit them.

Related pages

Notes and references

Other websites

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.