Loading AI tools

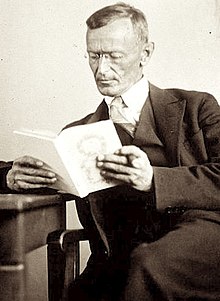

Siddhartha: An Indian Poem is a 1922 novel by Hermann Hesse that deals with the spiritual journey of self-discovery of a man named Siddhartha during the time of the Gautama Buddha.

Quotes

As translated by H. Rosner (Bantam: 1971)

- Siddhartha hatte begonnen, Unzufriedenheit in sich zu nähren. … Er hatte begonnen zu ahnen, daß sein ehrwürdiger Vater und seine anderen Lehrer, daß die weisen Brahmanen ihm von ihrer Weisheit das meiste und beste schon mitgeteilt, daß sie ihre Fülle schon in sein wartendes Gefäß gegossen hätten, und das Gefäß war nicht voll, der Geist war nicht begnügt, die Seele war nicht ruhig, das Herz nicht gestillt.

- Siddhartha had begun to feel the seeds of discontent within him. … He had begun to suspect that his worthy father and his other teachers, the wise Brahmins, had already passed on to him the bulk and best of their wisdom, that they had already poured the sum total of their knowledge into his waiting vessel; and the vessel was not full, his intellect was not satisfied.

- p. 5

- Siddhartha had begun to feel the seeds of discontent within him. … He had begun to suspect that his worthy father and his other teachers, the wise Brahmins, had already passed on to him the bulk and best of their wisdom, that they had already poured the sum total of their knowledge into his waiting vessel; and the vessel was not full, his intellect was not satisfied.

- Nein, nicht gering zu achten war das Ungeheure an Erkenntnis, das hier von unzählbaren Geschlechterfolgen weiser Brahmanen gesammelt und bewahrt lag.—Aber wo waren die Brahmanen, wo die Priester, wo die Weisen oder Büßer, denen es gelungen war, dieses tiefste Wissen nicht bloß zu wissen, sondern zu leben?

- No, this tremendous amount of knowledge, collected and preserved by successive generations of wise Brahmins, could not be easily overlooked. But where were the Brahmins, the wise men, the priests who were successful in not only having this most profound knowledge, but in living it?

- p. 7

- No, this tremendous amount of knowledge, collected and preserved by successive generations of wise Brahmins, could not be easily overlooked. But where were the Brahmins, the wise men, the priests who were successful in not only having this most profound knowledge, but in living it?

- The teaching which you have heard, however, is not my opinion, and its goal is not to explain the world to those who are thirsty for knowledge. Its goal is quite different; its goal is salvation from suffering. That is what Gotama teaches, nothing else.

- I have never seen a man look and smile, sit and walk like that, he thought. I, also, would like to look and smile, sit and walk like that, so free, so worthy, so restrained, so candid, so childlike and mysterious. A man only looks and walks like that when he has conquered his self. I also will conquer my self.

- p. 35

- Er blickte um sich, als sähe er zum ersten Male die Welt. Schön war die Welt, bunt war die Welt, seltsam und rätselhaft war die Welt! Hier war Blau, hier war Gelb, hier war Grün, Himmel floß und Fluß, Wald starrte und Gebirg, alles schön, alles rätselvoll und magisch, und inmitten er, Siddhartha, der Erwachende, auf dem Wege zu sich selbst. All dieses, all dies Gelb und Blau, Fluß und Wald, ging zum erstenmal durchs Auge in Siddhartha ein, war nicht mehr Zauber Maras, war nicht mehr der Schleier der Maya, war nicht mehr sinnlose und zufällige Vielfalt der Erscheinungswelt, verächtlich dem tief denkenden Brahmanen, der die Vielfalt verschmäht, der die Einheit sucht. Blau war Blau, Fluß war Fluß, und wenn auch im Blau und Fluß in Siddhartha das Eine und Göttliche verborgen lebte, so war es doch eben des Göttlichen Art und Sinn, hier Gelb, hier Blau, dort Himmel, dort Wald und hier Siddhartha zu sein. Sinn und Wesen war nicht irgendwo hinter den Dingen, sie waren in ihnen, in allem.

- „Wie bin ich taub und stumpf gewesen!” dachte der rasch dahin Wandelnde. „Wenn einer eine Schrift liest, deren Sinn er suchen will, so verachtet er nicht die Zeichen und Buchstaben und nennt sie Täuschung, Zufall und wertlose Schale, sondern er liest sie, er studiert und liebt sie, Buchstabe um Buchstabe. Ich aber, der ich das Buch der Welt und das Buch meines eigenen Wesens lesen wollte, ich habe, einem im voraus vermuteten Sinn zuliebe, die Zeichen und Buchstaben verachtet, ich nannte die Welt der Erscheinungen Täuschung, nannte mein Auge und meine Zunge zufällige und wertlose Erscheinungen.”

- All this yellow and blue, river and wood, passed for the first time across Siddhartha’s eyes. It was no longer the magic o Mara, it was no more the veil of Maya, it was no longer meaningless and the chance diversities of the appearances of the world, despised by deep-thinking Brahmins, who scorned diversity, who sought unity. … Meaning and reality were not hidden somewhere behind things, they were in them, in all of the,.

- How deaf and stupid I have been, he thought, walking on quickly. When anyone reads anything which he wishes to study, he does not despise the letters and punctuation marks, and call them illusion, chance and worthless shells, but he reads them, he studies them, he loves them, letter by letter. But I, who wished to read the book of the world and the book of my own nature, did presume to despise the letters and signs. I called the world of appearances, illusion. I called my eyes and tongue, chance.

- pp. 39-40

- The sun and moon had always shone; the rivers had always flowed and the bees had hummed, but in previous times all this had been nothing to Siddhartha but a fleeting and illusive veil before his eyes, regarded with distrust, condemned to be disregarded and ostracized from the thoughts, because it was not reality, because reality lay on the other side of the visible. But now his thoughts lingered on this side; he saw and recognized the visible and he sought his place in this world. He did not seek reality; his goal was not on any other side. The world was beautiful when looked at in this way—without any seeking, so simple, so childlike. The moon and the stars were beautiful, the brook, the shore, the forest and the rock, the goat and the golden beetle, the flower and the butterfly were beautiful. It was beautiful and pleasant to go through the world like that, so childlike, so awakened, so concerned with the immediate, without any distrust. …

- All this had always been and he had never seen it; he was never present. Now he was present and belonged to it. Through his eyes he saw light and shadows; through his mind he was aware of moon and stars.

- pp. 45-46

- He had never really found his self, because he had wanted to trap it in the net of thoughts. The body was certainly not the self, nor the play of senses, nor thought, nor understanding, nor acquired wisdom or art with which to draw conclusions and from already existing thoughts to spin new thoughts. No, this world of thought was still on the side, and it led to no goal when one destroyed the senses of the incidental self but fed it with thoughts and erudition. Both thought and the senses were fine things; behind both of them lay hidden the last meaning; it was worth while listening to them both, to play with both, neither to despise nor overrate either of them, but to listen intently to both voices.

- p. 47

- Although he found it so easy to speak to everyone, to live with everyone, to learn from everyone, he was very conscious of the fact that there was something which separated him from them. … He saw people living in a childish or animal-like way, which he both loved and despised. He saw them toiling, saw them suffer and grow gray about things that to him did not seem worth the price—for money, small pleasures and trivial honors. He saw them scold and hurt each other; he saw then lament over pains at which the Samana laughs, and suffer at deprivations which a Samana does not feel.

- pp. 69-70

- “You are like me; you are different from other people. You are Kamala and no one else, and within you there is a stillness and sanctuary to which you can retreat at any time and be yourself, just as I can. Few people have that capacity and yet everyone could have it.”

- “Not all people are clever,” said Kamala.

- “It has nothing to do with that, Kamala,” said Siddhartha. “Kamaswami is just as clever as I am and yet he has no sanctuary. Others have it who are only children in understanding. Most people, Kamala, are like a falling leaf that drifts and turns in the air, flutters, and falls to the ground. But a few others are like stars which travel one defined path: no wind reaches them, they have within themselves their guide and path.

- pp. 71-72

- Just as the potter’s wheel, once set in motion, still turns for a long time and then turns only very slowly and stops, so did the wheel of the ascetic, the wheel of thinking, the wheel of discrimination, still revolve for a long time in Siddhartha’s soul; it still revolved, but slowly and hesitatingly, and it had nearly come to a standstill. Slowly, like moisture entering the dying tree trunk, slowly filling and rotting it, so did the world and inertia creep into Siddhartha’s soul; it slowly filled his soul, made it heavy, made it tired, sent it to sleep. But on the other hand his senses became more awakened, they learned a great deal, experienced a great deal. … He had always felt different and superior to the others; he had always watch them a little scornfully, with a slightly mocking disdain, with that disdain which a Samana always feels towards the people of the world. If Kamaswami was upset, if he felt that he had been insulted, or if he was troubled with his business affairs, Siddhartha had always regarded him mockingly. But slowly and imperceptible, with the passing of the seasons, his mockery and feeling of superiority diminished. Gradually, along with his growing riches, Siddhartha himself acquired some of the characteristics of the ordinary people, some of their childishness and some of their anxiety. … His face was still more clever and intellectual than other people’s, but he rarely laughed, and gradually his face assumed the expressions which are so often found among rich people—the expressions of discontent, of sickliness, of displeasure, of idleness, of lovelessness. Slowly the soul sickness of the rich crept over him.

- Like a veil, like a thin mist, a weariness settled on Siddhartha, slowly, every day a little thicker, every month a little darker, every hear a little heavier. As a new dress grows old with time, loses its bright color, becomes stained and creased, the hems frayed and here and there weak and threadbare places, so had Siddhartha’s new life which he had begun after his parting from Govinda, become old. In the same way it lost its color and sheen with the passing of the years: creases and stains accumulated, and hidden in the depths, here and there already appearing, waited disillusionment and nausea. Siddhartha did not notice it. He only noticed that the bright and clear inward voice, the voice that had once awakened in him and had always guided him in his finest hours, had become silent.

- The world had caught him; pleasure, covetousness, idleness, and finally also that vice he had always despised and scorned as the most foolish—acquisitiveness. Property, possessions and riches had also finally trapped him. They were no longer a game and a toy. They had become a chain and a burden.

- pp. 76-79

- Like one who has eaten and drunk too much and vomits painfully, and then feels better, so did the restless man wish he could rid himself with one terrific heave of these pleasures, of these habits of this entirely senseless life. … It seemed to him that he had spent his life in an entirely worthless and senseless manner; he retained nothing vital, nothing in any way precious or worth while. He stood alone, like a shipwrecked man on the shore.

- p. 82

- When had he really experienced joy? … He had tasted it in the days of his boyhood, when … he far outstripped his contemporaries, when he excelled himself … in argument with the learned men. … And again as a youth when his continually soaring goal had propelled him in and out of the crowd of similar seekers, … when every freshly acquired knowledge only engendered a new thirst. Onwards, onwards, this is your path. He had heard this voice when he had left his home and chosen the life of the Samanas. … … How long was it now since he had heard this voice, since he had soared to any new heights? How flat and desolate his path had been! How many long years he had spent without any lofty goal, without any thirst, without any exaltation, content with small pleasures and yet never really satisfied! Without knowing it, he had endeavored and longed all these years to be like all the other people, like these children, and yet his life had been must more wretched and poorer than theirs, for their aims were not his, nor their sorrows his.

- pp. 83-84

- That was just the magic that had happened to him during his sleep— … he loved everything, he was full of joyous love towards everything that he saw. And it seemed to him that was just why he was previously so ill—because he could love nothing and nobody.

- p. 94

- How strange it is! Now, when I am no longer young, when my hair is fast growing gray, when strength begins to diminish, now I am beginning again like a child.

- p. 95

- When he now took the usual kind of travelers across, businessmen, soldiers and women, they no longer seemed alien to him as they once had. He did not understand or share their thoughts and views, but he shared with them life’s urges and desires. Although he had reached a high stage of self-discipline and bore his last wound well, he now felt as if these ordinary people were his brothers. Their vanities, desires and trivialities no longer seemed absurd to him; they had become understandable, lovable and even worthy of respect. There was the blind love of a mother for her child, the blind foolish pride of a fond father for his only son, the blind eager strivings of a young vain woman for ornament and the admiration of men. All these little simple, foolish, but tremendously strong, vital, passionate urges and desires no longer seemed trivial to Siddhartha. For their sake he saw people live and do great things, travel, conduct wars, suffer and endure immensely, and he loved them for it. He saw life, vitality, the indestructible and Brahman in all their desires and needs. These people were worthy of love and admiration in their blind loyalty, in their blind strength and tenacity. ... The men of the world were equal to the thinkers in every other respect and were often superior to them, just as animals in their tenacious undeviating actions in cases of necessity may often seem superior to human beings.

- pp. 129-130

- What could I say to you that would be of value, except that perhaps you seek too much, that as a result of your seeking you cannot find. … When someone is seeking, it happens quite easily that he only sees the thing that he is seeking; that he is unable to find anything, unable to absorb anything, because he is only thinking of the thing he is seeking, because he has a goal, because he is obsessed with his goal. Seeking means: to have a goal; but finding means: to be free, to be receptive, to have no goal. You, O worthy one, are perhaps indeed a seeker, for in striving towards your goal, you do not see many things that are under your nose.

- p. 140

- The sinner is not on the way to a Buddha-like state; he is not evolving, although our thinking cannot conceive things otherwise. No, the potential Buddha already exists in the sinner; his future is already there. The potential hidden Buddha must be recognized in him, in you, in everybody. The world, Govinda, is not imperfect or slowly evolving along a long path to perfection. No it is perfect at every moment; every sin already carries grace within it. .... The Buddha exists in the robber and dice player; the robber exists in the Brahmin. During deep meditation it is possible to dispel time, to see simultaneously all the past, present and future, and then everything is good, everything is perfect, everything is Brahman. Therefore it seems to me that everything that exists is good—death as well as life, sin as well as holiness, wisdom as well as folly. Everything is necessary, everything needs only my agreement, my assent, my loving understanding; then all is well with me and nothing can harm me. I learned through my body and soul that it was necessary for me to sin, that I needed lust, that I had to strive for property and experience nausea and the depths of despair in order to learn not resist them, in order to learn to love the world, and no longer compare it with some kind of desired imaginary world, some imaginary vision of perfection, but to leave it as it is, to love it and be glad to belong to it.

- pp. 143-144

- “But what you call a thing, is it something real, something intrinsic? Is it not only the illusion of Maya, only illusion and appearance?”

- “If they are illusion, then I also am illusion, so they are always of the same nature as myself.”

- p. 147

- It may be important to great thinkers to examine the world, to explain and despise it. But I think it is only important to love the world, not to despise it.

- p. 147

- I can love a stone, Govinda, and a tree or a piece of bark. These are things and one can love things. But one cannot love words. … Also with this great teacher, the thing to me is of greater importance than the words; his deeds and life are more important to me than his talk, the gesture of his hand is more important to me than his opinions. Not in speech or thought do I regard him as a great man, but in his deeds and life.

- pp. 146-148

As translated by: Gunther Olesch, Anke Dreher, Amy Coulter, Stefan Langer and Semyon Chaichenets, (Release Date: February, 2001)

(Full text multiple formats)

- In the shade of the house, in the sunshine of the riverbank near the boats, in the shade of the Sal-wood forest, in the shade of the fig tree is where Siddhartha grew up, the handsome son of the Brahman, the young falcon, together with his friend Govinda, son of a Brahman. The sun tanned his light shoulders by the banks of the river when bathing, performing the sacred ablutions, the sacred offerings.

- For a long time, Siddhartha had been partaking in the discussions of the wise men, practising debate with Govinda, practising with Govinda the art of reflection, the service of meditation. He already knew how to speak the Om silently, the word of words, to speak it silently into himself while inhaling, to speak it silently out of himself while exhaling, with all the concentration of his soul, the forehead surrounded by the glow of the clear-thinking spirit.

- He already knew to feel Atman in the depths of his being, indestructible, one with the universe.

- Joy leapt in his father’s heart for his son who was quick to learn, thirsty for knowledge; he saw him growing up to become great wise man and priest, a prince among the Brahmans.

- Bliss leapt in his mother’s breast when she saw him, when she saw him walking, when she saw him sit down and get up, Siddhartha, strong, handsome, he who was walking on slender legs, greeting her with perfect respect.

- Love touched the hearts of the Brahmans’ young daughters when Siddhartha walked through the lanes of the town with the luminous forehead, with the eye of a king, with his slim hips.

- But more than all the others he was loved by Govinda, his friend, the son of a Brahman. He loved Siddhartha’s eye and sweet voice, he loved his walk and the perfect decency of his movements, he loved everything Siddhartha did and said and what he loved most was his spirit, his transcendent, fiery thoughts, his ardent will, his high calling.

- Govinda knew: he would not become a common Brahman, not a lazy official in charge of offerings; not a greedy merchant with magic spells; not a vain, vacuous speaker; not a mean, deceitful priest; and also not a decent, stupid sheep in the herd of the many. No, and he, Govinda, as well did not want to become one of those, not one of those tens of thousands of Brahmans.

- Govinda: Siddhartha... we have become old men. It is unlikely for one of us to see the other again in this incarnation. I see, beloved, that you have found peace. I confess that I haven’t found it. Tell me, oh honourable one, one more word, give me something on my way which I can grasp, which I can understand! Give me something to be with me on my path. It is often hard, my path, often dark, Siddhartha.

- Siddhartha said nothing and looked at him with the ever unchanged, quiet smile. Govinda stared at his face, with fear, with yearning, suffering, and the eternal search was visible in his look, eternal not-finding. Siddhartha saw it and smiled (and said) Bend down to me! Bend down to me! Like this, even closer! Very close! Kiss my forehead, Govinda!

- But while Govinda with astonishment, and yet drawn by great love and expectation, obeyed his words, bent down closely to him and touched his forehead with his lips, something miraculous happened to him. While his thoughts were still dwelling on Siddhartha’s wondrous words, while he was still struggling in vain and with reluctance to think away time, to imagine Nirvana and Sansara as one, while even a certain contempt for the words of his friend was fighting in him against an immense love and veneration

- He no longer saw the face of his friend Siddhartha, instead he saw other faces, many, a long sequence, a flowing river of faces, of hundreds, of thousands, which all came and disappeared, and yet all seemed to be there simultaneously, which all constantly changed and renewed themselves, and which were still all Siddhartha. He saw the face of a fish, a carp, with an infinitely painfully opened mouth, the face of a dying fish, with fading eyes—he saw the face of a new-born child, red and full of wrinkles, distorted from crying—he saw the face of a murderer, he saw him plunging a knife into the body of another person—he saw, in the same second, this criminal in bondage, kneeling and his head being chopped off by the executioner with one blow of his sword—he saw the bodies of men and women, naked in positions and cramps of frenzied love—he saw corpses stretched out, motionless, cold, void—he saw the heads of animals, of boars, of crocodiles, of elephants, of bulls, of birds—he saw gods, saw Krishna, saw Agni—he saw all of these figures and faces in a thousand relationships with one another, each one helping the other, loving it, hating it, destroying it, giving re-birth to it, each one was a will to die, a passionately painful confession of transitoriness, and yet none of them died, each one only transformed, was always reborn, received evermore a new face...

- They were all constantly covered by something thin, without individuality of its own, but yet existing, like a thin glass or ice, like a transparent skin, a shell or mold or mask of water, and this mask was smiling, and this mask was Siddhartha’s smiling face, which he, Govinda, in this very same moment touched with his lips. And, Govinda saw it like this, this smile of the mask, this smile of oneness above the flowing forms, this smile of simultaneousness above the thousand births and deaths

- This smile of Siddhartha was precisely the same, was precisely of the same kind as the quiet, delicate, impenetrable, perhaps benevolent, perhaps mocking, wise, thousand-fold smile of Gotama, the Buddha, as he had seen it himself with great respect a hundred times. Like this, Govinda knew, the perfected ones are smiling.

- Not knowing any more whether time existed, whether the vision had lasted a second or a hundred years, not knowing any more whether there existed a Siddhartha, a Gotama, a me and a you, feeling in his innermost self as if he had been wounded by a divine arrow, the injury of which tasted sweet

- The face was unchanged, after under its surface the depth of the thousand-foldness had closed up again, he smiled silently, smiled quietly and softly, perhaps very benevolently, perhaps very mockingly, precisely as he used to smile, the exalted one.

- Deeply, Govinda bowed; tears he knew nothing of, ran down his old face; like a fire burned the feeling of the most intimate love, the humblest veneration in his heart. Deeply, he bowed, touching the ground, before him who was sitting motionlessly, whose smile reminded him of everything he had ever loved in his life, what had ever been valuable and holy to him in his life.

External links

- Hermann Hesse; Gunther Olesch, Anke Dreher, Amy Coulter, Stefan Langer, Semyon Chaichenets (February 1, 2001). Siddhartha. Gutenberg.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.