Loading AI tools

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchyov (17 April 1894 – 11 September 1971) served as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and as chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev stunned the communist world with his denunciation of Stalin's crimes, and embarked on a policy of de-Stalinization with his key ally Anastas Mikoyan. He sponsored the early Soviet space program, and made some reforms to domestic policy. After some false starts, and a narrowly avoided nuclear war over Cuba, he conducted successful negotiations with the United States to reduce Cold War tensions. His proclivity toward recklessness led the Kremlin leadership to strip him of power, replacing him with Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as Premier.

- They say that the Soviet delegates smile. That smile is genuine. It is not artificial. We wish to live in peace, tranquility. But if anyone believes that our smiles involve abandonment of the teaching of Marx, Engels and Lenin he deceives himself poorly. Those who wait for that must wait until a shrimp learns to whistle.

- Impromptu speech at a dinner for visiting East German dignitaries, Moscow (September 17, 1955), as reported by The New York Times (September 18, 1955), p. 19.

- Yes, today we have genuine Russian weather. Yesterday we had Swedish weather. I can't understand why your weather is so terrible. Maybe it is because you are immediate neighbours of NATO.

- At a Swedish-Soviet summit which began on March 30, 1956, in Moscow. The stenographed discussion was later published by the Swedish Government.as quoted in Raoul Wallenberg (1985) by Eric Sjöquist, p. 119 ISBN 9153650875

- Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will dig you in. (We will bury you.)

- Нравится вам или нет, но история на нашей стороне. Мы вас похороним!

- Remark to western ambassadors during a diplomatic reception in Moscow (18 November 1956) as quoted in Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Statesman, 1953-1964, Penn State Press, 2007, (2007) by Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, p. 893

- When it is a question of fighting against imperialism we can state with conviction that we are all Stalinists. We can take pride that we have taken part in the fight for the advance of our great cause against our enemies. From that point of view I am proud that we are Stalinists.

- Remark made at Kremlin New Year's Eve reception, December 31, 1956. Quoted in Khrushchev by Edward Crankshaw. ISBN 9781448205059

- I am very glad to hear this, since I come from the Ukraine. From now on I can sleep peacefully. I will immediately telegraph my daughter in Kiev.

- Khrushchev's reply when the Swedish prime minister Erlander assured him that Sweden had no intention of repeating the 1709 Battle of Poltava in eastern Ukraine between Russia and Sweden. From a Swedish-Soviet summit which began on March 30, 1956, in Moscow, as quoted in Raoul Wallenberg (1985) by Eric Sjöquist, p. 125 ISBN 9153650875

- If Adenauer were here with us in the sauna, we could see for ourselves that Germany is and will remain divided but also that Germany never will rise again.

- Said during a late night visit to a sauna with Finland's president Kekkonen in June 1957. Translated from Våldets århundrade (2001) by Max Jakobson, p. 220 ISBN 9174866389

- A man emaciated by a grave illness is at first treated by doctors gradually. Food is administered to him in small doses. If more is administered to the patient, it might kill him. And so we want to begin disarmament not with a full dose, although we are prepared even for a full dose. I have said already that the Western powers greatly distrust us. We, too, do not trust them in everything. And so, in order not to destroy a thing which is of great and vital importance to mankind, disarmament, we suggest to begin not with a cardinal but with a gradual solution to disarmament problems.

- Interview with Iverach McDonald, London Times (January 1958)

- The thought sometimes -- the unpleasant thought sometimes creeps up on me here as to whether perhaps Khrushchev was not invited here to enable you to sort of rub him in your sauce and to show the might and the strength of the United States so as to make him sort of … so as to make him shaky at the knees. If that is so, then if I came -- if it took me about 12 hours to get here, I guess it'll just -- it'll take no more than about 10½ hours to fly back.

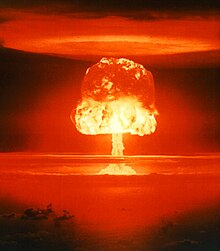

- I happened to read recently a remark by the American nuclear physicist W. Davidson, who noted that the explosion of one hydrogen bomb releases a greater amount of energy than all the explosions set off by all countries in all wars known in the entire history of mankind. And he, apparently, is right.

- Address to the United Nations, New York City (September 18, 1959), as reported by The New York Times (September 19, 1959), p. 8. The physicist quoted was eventually found to be William Davidon, associate physicist at Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois.

- We have come to this town where lives the cream of American art.… But just now I was told that I could not go to Disneyland. I asked "Why not? What is it? Do you have rocket-launching pads there?" I do not know. Just listen to what reason I was told: "We," which means the American authorities, "cannot guarantee your security if you go there." What is it? Is there an epidemic of cholera there or something? Or have gangsters taken over the place that can destroy me? Then what must I do? Commit suicide? … For me, this situation is inconceivable. I cannot find words to explain this to my people.

- Remarks during a Hollywood luncheon (19 September 1959), quoted in New York Times (20 September 1959) "Text of Khrushchev Debate With Skouras"

- Mr. President, call the toady of American imperialism to order.

- Remark in the United Nations General Assembly (12 October 1960),[specific citation needed] denouncing a speech by Philippines delegate Lorenzo Sumulong

- I have participated in two wars and know that war ends when it has rolled through cities and villages, everywhere sowing death and destruction. For such is the logic of war. If people do not display wisdom, they will clash like blind moles and then mutual annihilation will commence.… We and you ought not to pull on the ends of a rope in which you have tied the knot of war. Because the more the two of us pull, the tighter the knot will be tied. And then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you.

- Telegram to John F. Kennedy (26 October 1962)

- I see, Mr. President, that you too are not devoid of a sense of anxiety for the fate of the world understanding, and of what war entails. What would a war give you? You are threatening us with war. But you well know that the very least which you would receive in reply would be that you would experience the same consequences as those which you sent us. And that must be clear to us, people invested with authority, trust, and responsibility. We must not succumb to intoxication and petty passions, regardless of whether elections are impending in this or that country, or not impending. These are all transient things, but if indeed war should break out, then it would not be in our power to stop it, for such is the logic of war. I have participated in two wars and know that war ends when it has rolled through cities and villages, everywhere sowing death and destruction. [...] If people do not show wisdom, then in the final analysis they will come to a clash, like blind moles, and then reciprocal extermination will begin. [...] Mr. President, I appeal to you to weigh well what the aggressive, piratical actions, which you have declared the USA intends to carry out in international waters, would lead to. You yourself know that any sensible man simply cannot agree with this, cannot recognize your right to such actions. If you did this as the first step towards the unleashing of war, well then, it is evident that nothing else is left to us but to accept this challenge of yours. If, however, you have not lost your self-control and sensibly conceive what this might lead to, then, Mr. President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our countries dispose. Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.

- Department of State Telegram Transmitting Letter From Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy, October 26, 1962. As provided by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022.

- Don't you know how to paint? My grandson will paint it better! What is this? Are you men or damned pederasts? How can you paint like that? Do you have a conscience?

- Said to avant-garde artists Ely Bielutin and Ernst Neizvestny during a visit to their exhibition (1 December 1962)

- Politicians are the same all over. They promise to build a bridge even where there is no river.

- Comment on the construction of a bridge in Belgrade (22 August 1963), quoted in Chicago Tribune (22 August 1963) "Khrushchev Needles Peking"

- Berlin is the testicle of the West. When I want the West to scream, I squeeze on Berlin.

- Aug. 24, 1963, speech in Yugoslavia[citation needed]

- If you start throwing hedgehogs under me, I shall throw a couple of porcupines under you.

- As quoted in The New York Times (7 November 1963)

- I remember President Kennedy once stated... that the United States had the nuclear missile capacity to wipe out the Soviet Union two times over, while the Soviet Union had enough atomic weapons to wipe out the United States only once... When journalists asked me to comment... I said jokingly, "Yes, I know what Kennedy claims, and he's quite right. But I'm not complaining... We're satisfied to be able to finish off the United States first time round. Once is quite enough. What good does it do to annihilate a country twice? We're not a bloodthirsty people."

- As quoted in Khrushchev Remembers: The Last Testament (1974)

- My arms are up to the elbows in blood. That is the most terrible thing that lies in my soul.

- Told to Soviet playwright Nikolay Shatrov, as quoted in William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York: W.W. Norton, 2002)

"Secret Report to the 20th Party Congress of the CPSU"

"The Cult of the Individual and Its Consequences" (24 February 1956)

- Comrades! We must abolish the cult of the individual decisively, once and for all.

- Concerning Stalin's merits, an entirely sufficient number of books, pamphlets and studies had already been written in his lifetime. The role of Stalin in the preparation and execution of the socialist revolution, in the Civil War, and in the fight for the construction of socialism in our country, is universally known.

- The Stalinist Legacy (1984)

- When we analyze the practice of Stalin in regard to the direction of the party and the country, when we pause to consider everything which Stalin perpetrated, we must be convinced that Lenin's fear were justified. The negative characteristics of Stalin, which, in Lenin's time, were only incipient, transformed themselves during the last years into a grave abuse of power by Stalin, which caused untold harm.

- Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient cooperation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint and the correctness of his position was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation.

- We must affirm that the part had fought a serious fight against the Trotskyistes, rightists and bourgeois nationalists, and that it disarmed ideologically all the enemies of Leninism. This ideological fight was carried on successfully, as a result of which the party became strengthened and tempered. Here Stalin played a positive role.

- Stalin originated the concept of 'enemy of the people'. This term automatically rendered it unnecessary that the ideological errors of a man or men engaged in a controversy be proven; this term made possible the usage of the most cruel repression, violating all norms of revolutionary legality, against anyone who in any way disagreed with Stalin, against those who were only suspected of hostile intent, against those who had bad reputations. This concept 'enemy of the people' actually eliminated the possibility of any kind of ideological fight or the making of one's views known on this or that issue, even those of a practical character. In the main, and in actuality, the only proof of guilt used, against all norms of current legal science, was the 'confession' of the accused himself.

- When the fascist armies had actually invaded Soviet territory and military operations began, Moscow issued the order that the German fire was not to be returned. Why? It was because Stalin, despite evident facts, thought that the war had not yet started, that this was only a provocative action on the part of several undisciplined sections of the German Army, and that reaction might serve as a reason for the Germans to begin the war.

- The living will envy the dead.

- No instance of this statement, allegedly in reference to nuclear war, has been found in Khrushchev's writings or documented remarks, as indicated in Respectfully Quoted : A Dictionary of Quotations (1989). Herman Kahn used "the survivors [will] envy the dead" in his 1960 book On Thermonuclear War. In Russia the quote is usually attributed to the translation of Treasure Island by Nikolay Chukovsky: "А те из вас, кто останется в живых, позавидуют мертвым!" "Those of you who will be still alive will envy the dead", originally: "Them that die'll be the lucky ones." A precedent for all of these is Jeremiah 8:3, "Death shall be chosen rather than life by all the residue of them that remain."

- We cannot expect the Americans to jump from capitalism to communism, but we can aid their elected leaders in giving them small doses of socialism until suddenly they awake to find they have communism.

- This quotation circulated in American anti-communist propaganda during the years after Khrushchev's September 1959 visit to the United States, typically attributed as something he said three and a half months before the visit. A contemporary investigation by the Library of Congress and the US Information Agency found no source, although Khrushchev did refer to "small doses" in an entirely different context, quoted above. See "Khrushchev Could Have Said It" by Morris K. Udall

- Khrushchev was overthrown in October 1964 by a politburo disgruntled by his brinkmanship over Suez, Berlin, and Cuba and also opposed to his erratic search for coexistence with the United States. During his nine-year rule, Khrushchev had attempted to achieve the impossible: while striving to dismantle the repressive elements of Stalinism, he had used Stalinist measures to crush popular revolutions in Eastern Europe; while seeking to unify global communism, he had created a powerful rival in Mao’s China; while seeking to revive Marxist-Leninist revolutionary impulses in the Third World, he had not only raised Washington’s hackles but also embraced nationalist leaders who imprisoned their left-wing opposition; and while seeking détente with the United States and the end of NATO, his inflammatory language and nuclear threats had underscored the need for a united West. Despite their differences in age and temperament, Kennedy and Khrushchev were both hardened Cold Warriors who only dimly recognized the radical changes in the world landscape that were beginning to reduce the Superpowers’ control. Their successors, less experienced in diplomacy and more intent on domestic reforms, would create a dangerous pause in the Superpowers’ post-Berlin, post- Cuba search for détente.

- Carole C. Fink, Cold War: An International History (2017), p. 115

- Political conditions on the other side had also changed significantly as a result of the Sino-Soviet rupture. In the late 1950s, Mao, resentful of Moscow's refusal to support China's atomic weapons program, condemned Krushchev's abandonment of the doctrine of revolutionary warfare and his pursuit of peaceful coexistence. Krushchev, a critic of Mao's disastrous Great Leap Forward and belligerence toward his neighbors, in 1960 suddenly withdrew Soviet experts and reduced Soviet assistance to China. After the split became public at the Twenty-Second Party Congress in October 1961, Mao openly mocked Krushchev's retreat during the Cuban missile crisis, complained of Moscow's pro-New Delhi stance during the 1962 Sino-Indian border conflict, and denounced the test ban treaty as a means of preventing China from developing its own nuclear weapons. By the end of 1963 the two communist giants were openly competing for leadership of the revolutionary movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- Carole C. Fink, Cold War: An International History (2017), p. 125

- Our only "crime" is that in Bucharest we did not agree that a fraternal communist party like the Chinese Communist Party should be unjustly condemned; our only "crime" is that we had the courage to oppose openly, at an international communist meeting (and not in the marketplace) the unjust action of Comrade Khrushchev, our only "crime" is that we are a small Party of a small and poor country which, according to Comrade Khrushchev, should merely applaud and approve but express no opinion of its own. But this is neither Marxist nor acceptable. Marxism-Leninism has granted us the right to have our say and we will not give up this right for any one, neither on account of political and economic pressure nor on account of the threats and epithets that they might hurl at us. On this occasion we would like to ask Comrade Khrushchev why he did not make such a statement to us instead of to a representative of a third party. Or does Comrade Khrushchev think that the Party of Labor of Albania has no views of its own but has made common cause with the Communist Party of China in an unprincipled manner, and therefore, on matters pertaining to our Party, one can talk with the Chinese comrades? No, Comrade Khrushchev, you continue to blunder and hold very wrong opinions about our Party. The Party of Labor of Albania has its own views and will answer for them both to its own people as well as to the international communist and workers' movement.

- It is not we who behave like the Yugoslavs but you, comrade Khrushchev, who are using methods alien to Marxism-Leninism against our Party. You consider Albania as a market commodity which can be gained by one or lost by another. There was a time when Albania was considered a medium of exchange, when others thought it depended on them whether Albania should or should not exist, but that time came to an end with the triumph of the ideas of Marxism-Leninism in our country. You were repeating the same thing when you decided that you had "lost" Albania or that some one else had "won" it, when you decided that Albania is no longer a socialist country, as it turns out from the letter you handed to us on November 8, in which our country is not mentioned as a socialist country.

- Enver Hoxha, Reject the Revisionist Theses of the XX Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Anti-Marxist Stand of Krushchev's Group! Uphold Marxism-Leninism!, Speech Delivered by Enver Hoxha as Head of the Delegation of the Party of Labor of Albania Before the Meeting of 81 Communist and Workers Parties, Moscow, 16 November, 1960

- Nikita Khruschev was a difficult man to deal with, often very hard, always determined. But his peasant side which made him alternatively good-natured and cunning, also made him likeable.

- Muhammad Reza Pahlavi (1980) The Shah's Story, page 142

- Comrade Khrushchev often repeats that Socialism cannot be built with American wheat. I think it can be done by anyone who knows how to do it, while a person who doesn't know how to do it cannot build Socialism even with his own wheat. Khrushchev says we live on charity received from the imperialist countries … What moral right have those who attack us to rebuke us about American aid or credits when Khruschev himself has just tried to conclude an economic agreement with America?

- Josip Broz Tito, as quoted by Jasper Ridley, Tito: A Biography (Constable and Company Ltd., 1994), p. 348-349.

- He's a charming fellow between sentences.

- John Charles Daly, What's my Line?, 20 September 1959.

- The peoples of all our democracies are hungry for peace and security. For 20 years some of us have lived either at war or under the shadow of war. They yearn for some alleviation of the exertions and sacrifices that have been demanded of them. They hear the argument put forward that the development of nuclear weapons has rendered conventional forces obsolete and unnecessary, and that it is a waste of money and effort to continue to maintain them. They are asked by some to believe that the hydrogen bomb has rendered war impossible because it is so deadly that both sides would be annihilated. There is therefore a danger that the free peoples may be lulled into a sense of false security, and that they will succumb to the temptation to relax their efforts which are still essential, if peace is to be preserved, and if our freedom and way of life are to be safeguarded. We must therefore be very careful not to be misled by specious and wholly untenable arguments, or read more into the smiles of the Kremlin than the facts of the case warrant. After all, even Mr. Krushev has himself warned us against wishful thinking. Here is what he said at a Kremlin banquet as recently as a fortnight ago: "The West say that the Soviet leaders smile, but that their actions do not match their smiles. But I assure them that the smiles are sincere. They are not artificial. We wish to live in peace. But if anyone thinks that our smiles mean that we abandon the teachings of Marx and Lenin" (i.e. that the ultimate purpose of Soviet policy is world revolution),"or abandon our Communist road, then they are fooling themselves". In the circumstances I submit that our course is plain. If we are to achieve a lasting relaxation of tension between East and West, and with it practical measures for peace, we can only do so by maintaining our unity and continuing to build up our collective strength.

- Hastings Ismay, Speech at the Danish Society for the Atlantic Pact and Democracy, 30 September 1955

- And lastly, Chairman Khrushchev has compared the United States to a worn-out runner living on its past performance, and stated that the Soviet Union would out-produce the United States by 1970. Without wishing to trade hyperbole with the Chairman, I do suggest that he reminds me of the tiger hunter who has picked a place on the wall to hang the tiger's skin long before he his caught the tiger. This tiger has other ideas.

- President John F. Kennedy's 13th News Conferences on June 28, 1961 John Source: F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum

- In Thompson's mind was this thought: Khrushchev's gotten himself in a hell of a fix. He would then think to himself, "My God, if I can get out of this with a deal that I can say to the Russian people: 'Kennedy was going to destroy Castro and I prevented it.'" Thompson, knowing Khrushchev as he did, thought Khrushchev will accept that. And Thompson was right.

- Robert McNamara, The Fog of War (2003)

- Khrushchev relaxed somewhat the dead dictator’s regime without changing its basic institutions or laws: one-party rule remained in place, as did the ubiquitous secret police and censorship. Nevertheless, life for Soviet citizens eased considerably. Millions of concentration-camp inmates regained their freedom. Many victims of repression were rehabilitated, which did not benefit them but brought relief to their families. Limited contacts with foreign nationals were permitted once again. More visitors from abroad received entry visas, and more Soviet citizens could travel outside the USSR. The jamming of foreign short-wave broadcasts continued as before, but it was not foolproof, so that the Soviet public could obtain a more realistic picture of life abroad as well as at home. The effect was to open people’s eyes.

- Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (2003)

- Nikita Krushchev's eagerness to challenge U.S. interests around the world contributed to the spread of the Cold War in the Middle East, East Asia, Latin America, and even Africa. Krushchev's aggressiveness was motivated not only by a desire to take advantage of an opportunity to expand Soviet influence but also by the perceived Soviet need to fend off a growing challenge by China for leadership of the communist movement. Krushchev's willingness to engage the United States in a nuclear arms race was motivated primarily by his realization that the Soviet Union, despite the continuing development of its nuclear arsenal, was still vulnerable to an American nuclear strike. He undoubtedly believed that the best defense is a good offense and that a forward policy would conceal Soviet nuclear weakness while serving to pressure the West to resolve issues, such as Berlin, to the satisfaction of the Soviet Union. Krushchev's aggressiveness also made Soviet-American reconciliation impossible during the 1950s.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 133-134

- Krushchev's public rhetoric also made Soviet-American reconciliation difficult, if not impossible, early in Kennedy's presidency. On January 6, 1961, the Soviet leader declared his country would support "wars of national liberation" in the underdeveloped world. Krushchev's declaration, wrote the president's confidante and historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., "alarmed Kennedy more than Moscow's amiable signals assuaged him." Although Kennedy was willing to negotiate an end to the Cold War, the Third World challenge which Krushchev threw at him would have to be dealt with first.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 135

- In the opinion of another historian, Bruce Miroff, Kennedy's reaction to Krushchev's blustering revealed an acute inferiority complex, which the president manifested by a perverse need to prove his leadership capabilities. As a result, rather than ignoring or minimizing Krushchev's threats, as Eisenhower usually did, Kennedy personalized them and converted them into tests of will, in the process manufacturing crises that need not have been. "There was really nothing in that [Eisenhower] era comparable to the Berlin crisis of 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis of 1962," Miroff observes, both of which represented the closest approaches to a superpower nuclear war during the Cold War. For whatever reasons, whether they were primarily ideological, political, or psychological- and all were important- in formulating his initial response to the Soviet Union Kennedy chose to emphasize Krushchev's bellicose actions rather than his friendly gestures. Only after Kennedy had proved to the Soviet leader that he was not soft on communism would diplomacy make any headway during his presidency.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 136

- Partly to offset America's nuclear superiority, but primarily to deter another U.S.-backed invasion of Cuba, Krushchev decided in early 1962 to deploy on that island nation thirty-six medium-range ballistic missiles (with a range of 2,200 nautical miles). Since the United States had deployed Jupiter IRBMs in Turkey, the Soviet leader had no qualms about trying to do the same thing in Cuba. "It was high time," he recalled thinking in his own memoir, "America learned what it feels like to have her own land and her own people threatened."

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 142

- It is probable that Krushchev also wanted a dramatic way of achieving a breakthrough on the Berlin problem, and perhaps expected that the successful deployment of missiles in Cuba would do much to neutralize U.S. nuclear superiority, thereby enabling him to increase Soviet pressure on that beleaguered city. In addition, some analysts believe, the successful deployment of Soviet missiles in Cuba would distract attention from Krushchev's growing domestic problems, primarily the mediocre performance of Soviet agriculture, and solidify the leadership of the Soviet Union in the international communist movement, which was being increasingly challenged by the Chinese.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 142

- Ironically, the enhanced short-term prestige that Kennedy experienced in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis only produced greater long-term insecurity for his country. The humiliation Krushchev suffered at the hands of Kennedy during the missile crisis contributed to his removal from power in October 1964. The new Soviet leadership, headed by Leonid Brezhnev, was determined to avoid a repetition of the humiliation Krushchev had experienced. Beginning in early 1965, the Kremlin embarked on a massive expansion of the Soviet nuclear arsenal that would enable the Soviet Union to achieve nuclear parity with the United States by the end of the decade.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 144

- Let’s set the record straight. There is no argument over the choice between peace and war, but there is only one guaranteed way you can have peace—and you can have it in the next second—surrender. Admittedly there is a risk in any course we follow other than this, but every lesson in history tells us that the greater risk lies in appeasement, and this is the specter our well-meaning liberal friends refuse to face—that their policy of accommodation is appeasement, and it gives no choice between peace and war, only between fight and surrender. If we continue to accommodate, continue to back and retreat, eventually we have to face the final demand—the ultimatum. And what then? When Nikita Khrushchev has told his people he knows what our answer will be? He has told them that we are retreating under the pressure of the Cold War, and someday when the time comes to deliver the ultimatum, our surrender will be voluntary because by that time we will have weakened from within spiritually, morally, and economically. He believes this because from our side he has heard voices pleading for “peace at any price” or “better Red than dead,” or as one commentator put it, he would rather “live on his knees than die on his feet.” And therein lies the road to war, because those voices don’t speak for the rest of us.

- Ronald Reagan, "A Time for Choosing" speech, (1964)

- Both Khrushchëv and his successor Brezhnev asserted that communism around the world outdid the West’s advanced capitalist countries in freedom and welfare. They ignored the point that elections were pointless when a single candidate from one party alone was allowed to stand in them; they glossed over the detention of political, intellectual and religious dissenters in the Gulag. But Soviet leaders were frequently thought to score better on other matters. There was no unemployment in the USSR. Citizens were guaranteed shelter, heating, fuel, schooling, public transport and healthcare at little or no cost. Tourists to the Soviet Union reported that muggings were rare and graffiti scrawls practically unknown; and neon-light advertisements were nowhere to be seen. What is more, Soviet spokesmen castigated racism, imperialism and nationalism. The USSR was a multinational state. Its spokesmen insisted that it had eliminated the iniquities of imperialism, nationalism and racism. Although the European empires dissolved themselves in the 1950s and 1960s, the former colonies continued to face difficulties of economic dependency and under-development. Soviet Azerbaijan was compared favourably with ex-British Nigeria, ex-French Algeria and ex-Dutch Malaysia.

- Robert Service, Comrades: A History of World Communism (2009)

- in January 1961, she (Carol Ruth Silver) saw Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev bang his shoe on the table during his famous address declaring the Soviet Union's support for national liberation struggles in Cuba and Vietnam. Witnessing Khrushchev's historic challenge to U.S. hegemony in international affairs broadened Silver's thinking.

- Debra L. Schultz Going South: Jewish Women in the Civil Rights Movement (2002)

- Even so, the new leadership, among whom Nikita Khrushchev slowly emerged as the head, went ahead with gradually setting free many of those imprisoned in the GULag. While labor camps would continue to exist right up to the end of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev removed them as a key part of the country’s economy, which under Stalin had been completely dependent on prison labor. Hundreds of thousands of prisoners—political protesters, petty thieves, foreign soldiers, those who belonged to the “wrong” nationality, and those many who had no idea why they had been arrested—started to emerge from the camps, and struggled to get home or find a new place in society. These are the people the Russian Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn immortalized in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and the process Ilya Ehrenburg called “The Thaw.” But Khrushchev himself later admitted that the new leaders “were scared—really scared. We were afraid that the thaw might unleash a flood, which we wouldn’t be able to control and which would drown us.”

- Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A Global History (2017)

- The new Soviet leaders understood that some of Stalin’s policies had created the resistance that had boiled to the surface after his death, not just in East Germany but elsewhere as well. But they were also afraid that the East German rebellion could be repeated elsewhere if they were not careful. By late 1953 they had therefore developed what they called a “new course,” which was intent on reform without weakening the Communists’ monopoly on power. The main parts of the reform program were reducing the number of people who were arrested or otherwise excluded from society, amnesty for most political prisoners, cuts in heavy industry and defense industry output, and improvements in the production of food and consumer products.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A Global History (2017)

- Obituary, The New York Times (12 September 1971)

- "The Case of Khrushchev's Shoe" by Nina Khrushcheva (Nikita's granddaughter) in New Statesman (2 October 2000)

- "Nikita S. Khrushchev: The Secret Speech — On the Cult of Personality" (1956) at Modern History Sourcebook

- A "Stalinist" rebuttal of Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" from the CPUSA (1956)

- "Tumultuous, prolonged applause ending in ovation. All rise." Khrushchev's "Secret Report" and Poland (March 2006)

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.