Loading AI tools

It is by excusing nothing that pure love shows itself.

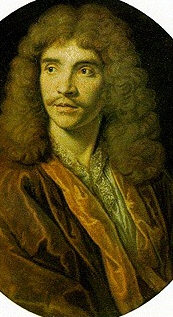

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, more famous as Molière (15 January 1622 – 17 February 1673) was a French theatre writer, director and actor, one of the masters of comic satire.

- Tirer les marrons du feu avec la patte du chat.

- Pull the chestnuts out of the fire with the cat's paw.

- L'Étourdi (1655), Act III, sc. v

- Pull the chestnuts out of the fire with the cat's paw.

- On ne meurt qu'une fois; et c'est pour si longtemps!

- We die only once, and for such a long time!

- Le Dépit Amoureux (1656), Act V, sc. iii

- We die only once, and for such a long time!

- Je fais toujours bien le premier vers: mais j'ai peine à faire les autres.

- I always make the first verse well, but I have trouble making the others.

- Les Précieuses Ridicules (1659), Act I, sc. xi

- I always make the first verse well, but I have trouble making the others.

- Le monde, chère Agnès, est une étrange chose.

- The world, dear Agnes, is a strange affair.

- L'École des Femmes (1662), Act II, sc. v

- The world, dear Agnes, is a strange affair.

- Une femme d'esprit est un diable en intrigue.

- A woman of wit is a devil of intrigue.

- L'École des Femmes (1662), Act III, sc. iii

- A woman of wit is a devil of intrigue.

- Il y a fagots et fagots.

- There are bundles and bundles.

- Le Médecin malgré lui (1666), Act i, scene 6. In this context, a fagot is a bundle of sticks, twigs or small tree branches bound together.

- There are bundles and bundles.

- Nous avons changé tout cela.

- We have changed all that.

- Le Médecin malgré lui (1666), Act ii, scene 6

- We have changed all that.

- Ah que je— Vous l'avez voulu, vous l'avez voulu, George Dandin, vous l'avez voulu, cela vous sied fort bien, et vous voilà ajusté comme il faut, vous avez justement ce que vous méritez.

- Ah that I— You would have it so, you would have it so; George Dandin, you would have it so! This suits you very nicely, and you are served right; you have precisely what you deserve.

- Georges Dandin (1668), Act I, sc. vii

- Ah that I— You would have it so, you would have it so; George Dandin, you would have it so! This suits you very nicely, and you are served right; you have precisely what you deserve.

- Que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère?

- What the devil was he doing in that galley?

- Les Fourberies de Scapin (1671), Act II, sc. vi

- What the devil was he doing in that galley?

- Ah! Il n'y a plus d'enfants!

- Ah, there are no longer any children!

- Le Malade Imaginaire (1673), Act II, sc. xi

- Ah, there are no longer any children!

- Presque tous les hommes meurent de leurs remèdes, et non pas de leurs maladies.

- Almost all men die of their remedies, not of their diseases.

- Le Malade Imaginaire (1673), Act III, sc. iii

- Almost all men die of their remedies, not of their diseases.

- Quare Opium facit dormire: … Quia est in eo Virtus dormitiva.

- Why Opium produces sleep: … Because there is in it a dormitive power.

- Le Malade Imaginaire (1673), Act III, sc. iii

- Why Opium produces sleep: … Because there is in it a dormitive power.

Tartuffe (1664)

Are always the first to attack their neighbors.

- Main article: Tartuffe

- Si l’emploi de la comédie est de corriger les vices des hommes, je ne vois pas par quelle raison il y en aura de privilégiés. Celui-ci est, dans l’État, d’une conséquence bien plus dangereuse que tous les autres ; et nous avons vu que le théâtre a une grande vertu pour la correction. Les plus beaux traits d’une sérieuse morale sont moins puissants, le plus souvent, que ceux de la satire ; et rien ne reprend mieux la plupart des hommes que la peinture de leurs défauts. C’est une grande atteinte aux vices que de les exposer à la risée de tout le monde. On souffre aisément des répréhensions ; mais on ne souffre point la raillerie. On veut bien être méchant, mais on ne veut point être ridicule.

- If the purpose of comedy be to chastise human weaknesses I see no reason why any class of people should be exempt. This particular failing is one of the most damaging of all in its public consequences and we have seen that the theatre is a great medium of correction. The finest passages of a serious moral treatise are all too often less effective than those of a satire and for the majority of people there is no better form of reproof than depicting their faults to them: the most effective way of attacking vice is to expose it to public ridicule. People can put up with rebukes but they cannot bear being laughed at: they are prepared to be wicked but they dislike appearing ridiculous.

- Preface, as translated by John Wood in The Misanthrope and Other Plays (Penguin, 1959), p. 101

- Variant translation: People do not mind being wicked; but they object to being made ridiculous.

- If the purpose of comedy be to chastise human weaknesses I see no reason why any class of people should be exempt. This particular failing is one of the most damaging of all in its public consequences and we have seen that the theatre is a great medium of correction. The finest passages of a serious moral treatise are all too often less effective than those of a satire and for the majority of people there is no better form of reproof than depicting their faults to them: the most effective way of attacking vice is to expose it to public ridicule. People can put up with rebukes but they cannot bear being laughed at: they are prepared to be wicked but they dislike appearing ridiculous.

- Vous êtes un sot en trois lettres, mon fils.

- You are a fool in three letters, my son.

- Act I, sc. i

- You are a fool in three letters, my son.

- Contre la médisance il n'est point de rempart.

- There is no rampart that will hold out against malice.

- Act I, sc. i

- There is no rampart that will hold out against malice.

- Ceux de qui la conduite offre le plus à rire

Sont toujours sur autrui les premiers à médire.- Those whose conduct gives room for talk

Are always the first to attack their neighbors.- Act I, sc. i

- Those whose conduct gives room for talk

- À votre nez, mon frère, elle se rit de vous.

- In your face, my brother, she is laughing at you.

- Act I, sc. v

- Variant translation:

- She is laughing in your face, my brother.

- In your face, my brother, she is laughing at you.

- Une femme a toujours une vengeance prête.

- A woman always has her revenge ready.

- Act II, sc. ii

- A woman always has her revenge ready.

- Couvrez ce sein que je ne saurais voir.

Par de pareils objets les âmes sont blessées.- Cover that bosom that I must not see:

Souls are wounded by such things.- Act III, sc. ii

- Cover that bosom that I must not see:

- Pour être dévot, je n'en suis pas moins homme.

- Although I am a pious man, I am not the less a man.

- Act III, sc. iii

- Although I am a pious man, I am not the less a man.

- Le scandale du monde est ce qui fait l'offense,

Et ce n'est pas pécher que pécher en silence.- To create a public scandal is what's wicked;

To sin in private is not a sin.- Act IV, sc. v

- To create a public scandal is what's wicked;

- Je l'ai vu, dis-je, de mes propres yeux vu.

- I saw him, I say, saw him with my own eyes.

- Act V, sc. iii

- I saw him, I say, saw him with my own eyes.

Le Misanthrope (1666)

- Sur quelque préférence une estime se fonde,

Et c'est n'estimer rien qu'estimer tout le monde.- On some preference esteem is based;

To esteem everything is to esteem nothing.- Act I, sc. i

- On some preference esteem is based;

- Et c’est une folie, à nulle autre, seconde,

De vouloir se mêler de corriger le monde.- The world will not reform for all your meddling.

- As published in Le Misanthrope, Molière, tr. Curtis Hidden Page, G.P. Putnam’s Sons (1913), p. 12

- Variant translation: Of all follies there is none greater than wanting to make the world a better place.

- As contained in The Columbia Dictionary of Quotations, ed. Robert Andrews, Columbia University Press (1993), p.772 : ISBN 0231071949

- Act I, sc. 1, lines 155-156 (Philinte)

- The world will not reform for all your meddling.

- C'est un parleur étrange, et qui trouve toujours

L'art de ne vous rien dire avec de grands discours.- He's a wonderful talker, who has the art

Of telling you nothing in a great harangue.- Act II, sc. iv

- He's a wonderful talker, who has the art

- Que de son cuisinier il s'est fait un mérite,

Et que c'est à sa table à qui l'on rend visite.- He makes his cook his merit,

And the world visits his dinners and not him.- Act II, sc. iv

- He makes his cook his merit,

- On voit qu'il se travaille à dire de bons mots.

- You see him laboring to produce bons mots.

- Act II, sc. iv

- You see him laboring to produce bons mots.

- Plus on aime quelqu'un, moins il faut qu'on le flatte:

À rien pardonner le pur amour éclate.- The more we love our friends, the less we flatter them;

It is by excusing nothing that pure love shows itself.- Act II, sc. iv

- The more we love our friends, the less we flatter them;

- Les doutes sont fâcheux plus que toute autre chose.

- Doubts are more cruel than the worst of truths.

- Act III, sc. v

- Doubts are more cruel than the worst of truths.

- On peut être honnête homme et faire mal des vers.

- Anyone may be an honorable man, and yet write verse badly.

- Act IV, sc. i

- Anyone may be an honorable man, and yet write verse badly.

- Si de probité tout était revêtu,

Si tous les cœurs était francs, justes et dociles,

La plupart des vertus nous seraient inutiles,

Puisqu'on en met l'usage à pouvoir sans ennui

Supporter dans nos droits l'injustice d'autrui.- If everyone were clothed with integrity,

If every heart were just, frank, kindly,

The other virtues would be well-nigh useless,

Since their chief purpose is to make us bear with patience

The injustice of our fellows.- Act V, sc. i

- If everyone were clothed with integrity,

- C'est un merveilleux assaisonnement aux plaisirs qu'on goûte que la présence des gens qu'on aime.

- It is a wonderful seasoning of all enjoyments to think of those we love.

- Act V, sc. iv

- It is a wonderful seasoning of all enjoyments to think of those we love.

Amphitryon (1666)

- J'aime mieux un vice commode,

Qu'une fatigante vertu.- I prefer an accommodating vice

To an obstinate virtue.- Act I, sc. iv

- I prefer an accommodating vice

- Le véritable Amphitryon,

Est l'Amphitryon où l'on dine.- The true Amphitryon

Is the Amphitryon who gives dinner.- Act III, sc. v

- The true Amphitryon

- Le Seigneur Jupiter sait dorer la pilule.

- My lord Jupiter knows how to sugarcoat the pill.

- Act III, sc. x

- My lord Jupiter knows how to sugarcoat the pill.

L'Avare (1668)

- [J]e veux que tu me dises à qui lu parles quand lu dis cela.

Je parle... je parle à mon bonnet.- Tell me to whom you are addressing yourself when you say that.

I am addressing myself—I am addressing myself to my cap.- Act I, scene iii

- Tell me to whom you are addressing yourself when you say that.

- Les beaux yeux de ma cassette.

- The beautiful eyes of my cash-box.

- Act V, scene iii

- The beautiful eyes of my cash-box.

- Vous parlez devant un homme à qui tout Naples est connu.

- You are speaking before a man to whom all Naples is known.

- Act V, scene v

- You are speaking before a man to whom all Naples is known.

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670)

- Tout ce qui n'est point prose, est vers; et tout ce qui n'est point vers, est prose.

- All that is not prose is verse; and all that is not verse is prose.

- Act II, sc. iv

- All that is not prose is verse; and all that is not verse is prose.

- Par ma foi, il y a plus de quarante ans que je dis de la prose, sans que j'en susse rien.

- Good heavens! For more than forty years I have been speaking prose without knowing it.

- Act II, sc. iv

- Good heavens! For more than forty years I have been speaking prose without knowing it.

- Ah, la belle chose que de savoir quelque chose.

- Ah, it's a lovely thing to know a thing or two.

- Jurons, ma belle,

Une ardeur éternelle.- Let's swear, my beauty, An eternal ardor.

- Act IV, sc. i

- Let's swear, my beauty, An eternal ardor.

- Je le soutiendrai devant tout le monde.

- I will maintain it before the whole world.

- Act IV, sc. iii

- I will maintain it before the whole world.

Les Femmes Savantes (1672)

- La grammaire qui sait régenter jusqu'aux rois.

- Grammar, which knows how to control even kings.

- Act II, sc. vi. An apparent reference to Sigismund I, at the Council of Constance, 1414, said to a prelate who had objected to his Majesty's grammar, "Ego sum rex Romanus, et supra grammaticam" (I am the Roman emperor, and am above grammar).

- Grammar, which knows how to control even kings.

- Il est de sel attique assaisonné partout.

- It is seasoned throughout with Attic salt.

- Act III, sc. ii

- It is seasoned throughout with Attic salt.

- Un sot savant est sot plus qu'un sot ignorant.

- A learned fool is more foolish than an ignorant one.

- Act IV, sc. iii

- A learned fool is more foolish than an ignorant one.

- Il faut manger pour vivre, et non pas vivre pour manger.

- One must eat to live, and not live to eat.

- L'Avare (1668), Act III, sc. i.

- Firstly, an inaccurate sourcing: in Act III, yes—but in Scene I, no: rather, in Scene V—HARPAGON, VALÈRE, MASTER JACQUES (see, e.g., the Project Gutenberg HTML version of the English translation: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6923/6923-h/6923-h.htm). Secondly, a misattribution made clear by the Molière text—the character in the play, VAL, obviously points out that the quote refers to a "saying of one of the ancients" (and the quote is precisely written in quotation marks as well), in the full line of dialogue below:

- Know, Master Jacques, you and people like you, that a table overloaded with eatables is a real cut-throat; that, to be the true friends of those we invite, frugality should reign throughout the repast we give, and that according to the saying of one of the ancients, "We must eat to live, and not live to eat."

- The "ancients" to which VAL/Molière refers is Cicero, Diogenes Laertius, and the oldest known attribution, Socrates (whom Laertius explicitly attributes—and Cicero presumably invokes). Various books of quotations document this—e.g., Elizabeth Knowles' 2006 The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (http://books.google.com/books?id=r2KIvsLi-2kC&dq=%22one+must+eat+to+live+not+live+to+eat%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s) and Jennifer Speake's 1982 A Dictionary of Proverbs (http://books.google.com/books?id=-IpkOkM3IfEC&dq=%22one+must+eat+to+live+not+live+to+eat%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s): the former lists the quote as "a proverbial saying, late 14th century, distinguishing between necessity and indulgence; Diogenes Laertius says of Socrates, 'he said that other men live to eat, but eats to live.' A similar idea is found in the Latin of Cicero, 'one must eat to live, not live to eat'"; the latter, reiterates this. Moreover, in William Shepard Walsh's 1909 Handy-book of Literary Curiosities, he adds that "According to Plutarch, what Socrates said was, 'Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.'" He also adds that Atheneus quotes similarly to Laertius, as well as explores other later variations (http://books.google.com/books?id=hrJkAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s).

- L'Avare (1668), Act III, sc. i.

- One must eat to live, and not live to eat.

- Molière at Project Gutenberg

- Molière's complete works (in French)

- Works by Molière at Project Gutenberg

- Molière's works online at toutmoliere.net (in French)

- Molière's works online at site-moliere.com

- Molière's works online at InLibroVeritas.net

- Molière's works online at classicistranieri.com

- Biography, Bibliography, Analysis, Plot overview at biblioweb.org (in French)

- Moliere's Verses Plays - Publication, Statistics, Words Research (in French)

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.