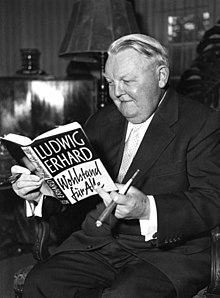

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard (4 February 1897 – 5 May 1977) was a German politician affiliated with the CDU and the second Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) from 1963 until 1966. He is often famed for leading German postwar economic reforms and economic recovery ("Wirtschaftswunder," German for "economic miracle") in his role as Minister of Economic Affairs under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer from 1949 to 1963. During that period he promoted the concept of the social market economy (soziale Marktwirtschaft), on which Germany's economic policy in the 21st century continues to be based. In his tenure as chancellor, however, Erhard failed to win confidence in his handling of a budget deficit and his direction of foreign policy, and his popularity waned. He resigned his chancellorship on 1 December 1966.

Quotes

- [Erhard said his] ambition was to drive up the German standard of living until it approximated to that of the United States. That could not be achieved overnight, but it could be done, for the standard of living in the United States was determined not by the climate but by a successful economic policy.

- Speech to the European Conference of the Association of German Industry in Trier, quoted in The Times (3 November 1952), p. 6

- [Erhard] forecast that this year German exports would reach a volume of 16,000m. marks. He recalled that in 1948, when exports totalled 2,000m. marks, he had calculated that in 1952 they might be 8,000m. marks. ... a balanced budget could be achieved in the long run only by a steadily rising volume of goods, a greater national income, higher productivity, and increased national wealth. To-day the Federal Republic had virtually attained full employment.

- Speech (November 1952), quoted in The Times (3 November 1952), p. 6

- [Erhard said that] no other country had advanced to such a degree as western Germany in the past five years. They could not stand still, however; production must be raised and consumption increased. ... Abroad...it had become the habit to speak about the German "miracle". In fact, there was no miracle. What had been achieved in the past five years was due to German initiative and industriousness. Western Germany to-day had one of the soundest currencies in the world; bottlenecks had been overcome and the trade balance was favourable. He looked forward to widening consumption so that such things as refrigerators, washing machines, motor-cycles, and motor-cars could be made available to new classes of the community. Plans were in hand for stimulating consumption to this end.

- Speech (2 March 1953), quoted in The Times (3 March 1953), p. 6

- National autonomy in economic matters should not be an obstacle to a free world economic system. But to achieve free convertibility within the European Payments Union only would lead to further upheavals. The dollar and the pound sterling should be included in any such step, if a new single world market was to be created. A free political order implied a free economic order; this would stand foremost amongst the preoccupations of the new Bundestag.

- Speech to the opening of the fourth German Industrial Fair in Berlin (26 September 1953), quoted in The Times (28 September 1953), p. 5

- [Erhard said that] in the next four years he would fight unrelentingly against all forms of restrictive practices. The threat to the German economy came not so much from the Social Democrats as from opposition within the economy to free competition. "I will not retreat one step from my stand on the subject of cartels and professional rings. It will be a hard fight." He warned industrialists that they endangered the whole economic system by their predilection for cartels in the search for an illusory security. There was no security for the owner of a business.

- Speech to United Action for a Social and Liberal Economy (Soziale Marktwirtschaft) (19 November 1953), quoted in The Times (20 November 1953), p. 6

- [Erhard] emphasized that the aim of a common market was to free the movement of goods and capital. It did not exclude differentiation in tariffs, but he had been at pains to allay any anxiety lest the establishment of a common market by the six countries would mean discrimination against Britain. He believed that he had succeeded in dissipating some of the fears regarding European integration.

- Speech to correspondents after his visit to London (24 February 1956), quoted in The Times (25 February 1956), p. 5

- The German economy compared very favourably with the situation in other countries: the average income of workers here had risen in the past two years by 16 per cent. while the cost of living had gone up by only four per cent. He was anxious to avoid making too little of the rise in prices, but pointed out that whereas the cost of living in the Federal Republic was now 13 per cent. above the 1950 figure, in Britain and France the rise over the same period was a third or more.

- Speech in the Bundestag (22 June 1956), quoted in The Times (23 June 1956), p. 5

- [Erhard said that] a new phase in the development of the German free economy would begin with the transformation of publicly owned enterprises into joint stock companies in which those with small savings could invest.

- Speech to the Christian Democratic congress in Hamburg (14 May 1957), quoted in The Times (15 May 1957), p. 9

- In a community of free people the freedom of economic activity is an inseparable part of the whole, and only this freedom will ensure a life worth living.

- Message to the international industrial development conference in San Francisco, quoted in The Times (16 October 1957), p. 7

- A collectivist-totalitarian economic system, which in the final analysis serves only to glorify and increase the power of the state, can achieve great success in the easily controllable field of the basic industries but it will always remain incapable of serving man, in other words of providing the rich abundance of goods which gives the individual consumer a free choice and which enriches and beautifies his life.

- The Economics of Success (D. van Nostrand & Co., 1963), p. 281

- As I have said time and again, the focal point of our economy is the individual.

- The Economics of Success (D. van Nostrand & Co., 1963), pp. 283–284

- Any liberal system must proceed from the assumption that freedom is one and indivisible and that elementary human freedom in all spheres of life must go hand in hand with political, religious, economic and spiritual freedom. The strategy of collectivist thinking has always been to split up this most essential and most universal of human values as a means of making inroads into the free system itself.

- The Economics of Success (D. van Nostrand & Co., 1963), pp. 291–292

- Who carries the real responsibility and who is responsible to whom? Naturally the Christian reply is: Let every man carry responsibility, and in fact each man is responsible to his conscience, his fellowmen and finally to God. But when I, for example, have the pleasure of holding discussions with representatives of various groups, I seldom feel that they are aware of this responsibility; on the contrary, I hear talk of nothing but a unilateral responsibility to the interests they are representing. In such cases, if the concept of 'responsibility' is not turned upside-down, it is at least so devalued and falsified that one can only speak of rank misuse.

- The Economics of Success (D. van Nostrand & Co., 1963), p. 379

- Freedom can be saved only for those who are willing to hold and defend it, and for whom it means more than a desirable, but not really essential luxury. Freedom demands above all self-restraint, and it does not flourish in an atmosphere that is indifferent to values. Even where we speak of individual freedom, we think of it in relation to the human conscience, and having its proper place in the community and the body social. I repeat what I have often said: "Freedom without order will only too easily drift into chaos—order without freedom will deliver us to coercion."

- Speech to the Mont Pelerin Society in Aviemore, Scotland ("On Freedom and Dissent") (September 1968), quoted in Review of Social Economy Vol. 27, No. 1 (March 1969), p. 40

Quotes about Erhard

- Erhard was a man who had his moment in history and grasped it. As head of the Economic Department of the administration which preceded the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany, he was the author of the decision to combine the currency reform of 1948 with the abolition of rationing, and of restrictive regulations concerning production, distribution and capital movements. Many have argued that Germany’s ‘economic miracle’ (and not less the political miracle) owes much to these decisions which at the time were regarded as either unrealistic or indefensible by many, including the Occupation Powers.

- Ralf Dahrendorf, quoted in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (1987), pp. 1-2

- It seemed a miracle when West Germany—a defeated and devastated country—became one of the strongest economies on the continent of Europe in less than a decade. It was the miracle of a free market. Ludwig Erhard, an economist, was the German Minister of Economics. On Sunday, the twentieth of June, 1948, he simultaneously introduced a new currency, today's Deutsche Mark, and abolished almost all controls on wages and prices. He acted on a Sunday, he was fond of saying, because the offices of the French, American, and British occupation authorities were closed that day. Given their favorable attitudes towards controls, he was sure that if he had acted when the offices were open, the occupation authorities would have countermanded his orders. His measures worked like a charm. Within days the shops were full of goods. Within months the German economy was humming away.

- Rose and Milton Friedman, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement (1980), p. 56

- Thomas Hazlett: Do you have any examples in mind of countries that, once having flirted with socialism or the welfare state, have been able to reinstitute the rule of law?

Friedrich Hayek: Oh, very clearly Germany after World War II, although in that case it was really the achievement of a single man, almost.

Hazlett: Ludwig Erhard?

Hayek: Ludwig Erhard, yes.- Interview (12 November 1978), quoted in Noble Prize-Winning Economist Friedrich A. von Hayek (1983), p. 341

- May I tell you the story of when I last spoke to Dr Ludwig Erhard? We were alone for a moment and he turned to me and said, “I hope you don't misunderstand me when I speak of a social market economy (sozialen Marktwirtschaft). I mean by that that the market economy as such is social, not that it needs to be made social.”

- Friedrich Hayek, Encounter (May 1983), quoted in The Times (21 November 1983), p. 11

- Ludwig Erhard...deserves far greater credit for the restoration of a free society in Germany than he is given for either inside or outside Germany... It must be admitted, however, that Erhard could never have accomplished what he did under bureaucratic or democratic constraints. It was a lucky moment when the right person in the right spot was free to do what he thought right, although he could never have convinced anybody else it was the right thing.

- Friedrich Hayek, 'The Rediscovery of Freedom: Personal Recollections' (1983), in Peter G. Klein (ed.), The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, Vol. IV: The Fortunes of Liberalism: Essays on Austrian Economics and the Ideal of Freedom (1992), pp. 193-194

- Heartiest congratulations on your great victory. I look forward to an early chance to meet with you again and to discuss our great common tasks in working for the peace of Europe, the reunion of Germany, and the steady growth of the Atlantic community.

- Lyndon B. Johnson; Message to Chancellor Erhard on His Victory in the German Elections Online, The American Presidency Project; 20 September 1965

- In January 1947, the US and Britain established a common economic policy for their zones. France joined the following year, making it the ‘Trizone’. The economist Ludwig Erhard was appointed as director of the Economic Council and oversaw the smooth transition to the new currency, the Deutschmark. He coupled it with eliminating both price controls and rationing. Erhard’s bold economic policy inspired a recovery that eventually enabled political reconstruction based on a constitution approved by the Allied Powers.

- Henry Kissinger, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy (2021), p. 39

- Like everyone else, I was familiar with Erhard's heavy bulk, and I knew his reputation for stubbornness. But when I met him, I found that he was subtle and highly intelligent – although we did not always agree. The prestige he enjoyed was well deserved: he had shown clear-sighted courage in successfully imposing and carrying out his ideas. He had no reason to doubt the superiority of the so-called ‘liberal’ economic policies that had worked so well in his own country. He was no nationalist, but the Schuman Plan had no place in his vision of an international economy based on pure free trade. Where we were proposing a code of good conduct, he scented the danger of dirigisme; where we were organizing European solidarity, he suspected protectionism.

- Jean Monnet, Memoirs (1978), p. 351

- What Erhard said was breath-taking in its simplicity. Provided the state defends the currency, he said, there is no need to control prices, wages, goods, capital or anything else. In fact, so long as these controls remain, we shall continue to suffer from both inflation and scarcity. Abolish the lot and all will come right. The miracle was that he got away with being allowed to do it. ... In the early stages of his policy, Erhard was surrounded by capitalists and unionists, economists and bankers, crying “Woe, woe” and warning of the dire and imminent consequences of removing what they imagined were the foundations on which the fabric of things rested. As he used to say, “My room resounds with catastrophe from morn to night.” But he was right, and they were wrong: the new mark stayed rock hard and Germany in a decade was contemplating the economies of her victors with patronising contempt.

- Enoch Powell, speech to the Hounslow Chamber of Commerce (22 June 1977), quoted in Enoch Powell, A Nation or No Nation? Six Years in British Politics, ed. Richard Ritchie (1978), p. 128

- In West Germany and here in Berlin, there took place an economic miracle, the Wirtschaftswunder [Miracle on the Rhine]. Adenauer, Erhard, Reuter, and other leaders understood the practical importance of liberty -- that just as truth can flourish only when the journalist is given freedom of speech, so prosperity can come about only when the farmer and businessman enjoy economic freedom. The German leaders -- the German leaders reduced tariffs, expanded free trade, lowered taxes. From 1950 to 1960 alone, the standard of living in West Germany and Berlin doubled.

- Ronald Reagan, Brandenburg Gate Speech, 12 June 1987

- Ludwig Erhard had by this time [1975] retired from any involvement in active politics, but apparently he had heard that my politics (and economics) were sufficiently different (that is to say similar to his own) to make a discussion appealing. I was glad to discover that the former Chancellor, as well as being the architect of German prosperity, had a considerable presence and shrewdness. He asked me a number of searching questions about my economic approach, at the end of which he seemed satisfied. I felt I had performed well in an important tutorial.

- Margaret Thatcher, The Path to Power (1995), p. 344

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.