Loading AI tools

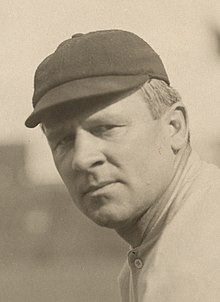

John Joseph McGraw (April 7, 1873 – February 25, 1934) is considered to be one of the greatest managers in baseball history. He started his baseball career in 1891 as a player with the Baltimore Orioles of the American Association. He took his first managing job in 1899 with the Orioles, but his greatest managerial success would come with the New York Giants, as he went on to manage that team for 30 years. When he retired from baseball in 1932, he had 2,763 managerial wins (second all-time behind Connie Mack) and had led his teams to 10 pennants.

| This article about a sportsperson is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

- McGraw was an improviser, a teacher. He brought much to the game that keeps baseball fresh and suspenseful today—the hit-and-run play, the steal, the squeeze play, the uses of the bunt and the defenses against it. He helped turn the game into a thing of fluid beauty, infielders charging the plate or roaming far from their bases, outfielders moving with each pitch, racing in for base hits before them, backing each other in the outfield, entering the infield itself on rundown plays. Yet when the game changed radically, with the introduction of the livelier baseball, McGraw naturally shifted to a power emphasis, founding his team about such men as George Kelly, Bill Terry, Mel Ott. He knew, too, that the old pitching style of permitting a man to hit a deadened ball because it would then be caught in the big fields had to be changed, and his staffs led the league year after year in strikeouts, in earned-runs.

- Hano, Arnold (1967). Greatest Giants of Them All. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 248–249.

- He wanted to win so badly it killed him. But before it killed him, it elevated the game of baseball, at the Polo Grounds, to a grim spectacle of play-war. The analogy fits McGraw. He reminds you more of a battlefield general than he does a sportsman, and if he reminds you of a general, it would be a man who combined the fury of a Patton and the spectacular, yet knowledgeable, flair of MacArthur. Perhaps this desire to win occasionally overflowed its normal limits and became an obsession; perhaps the grimness darkened the sport at times. This was his weakness, for McGraw was not infallible; McGraw was not perfect. Perfection is lifeless, mechanical, uncaring. McGraw was never uncaring. If he was anything, he was a man who cared.

- Hano. Greatest Giants of Them All. p. 250.

- In 1884, when diphtheria swept through his village, he was a slight, eager eleven-year-old whose proudest possession was the battered baseball he had been allowed to order from the Spalding catalogue. He watched helplessly as, one by one, his mother and four of his brothers and sisters died. His father took out his grief and anger on his son, beating him so often and so mercilessly that at twelve he feared for his life and ran away from home.

- Ward, Geoffrey C. and Ken Burns. Baseball: An Illustrated History. Random House LLC, 1996. ISBN: 0679765417, 9780679765417

- He supported himself at odd jobs until he won himself a place on the Olean (New York) professional team at sixteen and never again willingly took orders from any man. Although he was short and weighed barely 155 pounds, he held far bigger base runners back by the belt, blocked them, tripped them, spiked them - and rarely complained when they did the same to him.

- Ibid.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.