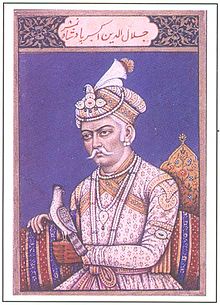

Akbar

3rd Mughal emperor from 1556 to 1605 From Wikiquote, the free quote compendium

Abu'l-Fath Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar, popularly known as Akbar I (IPA: [əkbər], literally "the great"; 15 October 1542– 27 October 1605), and later Akbar the Great (Urdu: Akbar-e-Azam; literally "Great the Great"), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expand and consolidate Mughal domains in India.

Quotes

- راستی موجب رضایٔ خداست

کس ندیدم که گم شد از رہ راست - Akbar – The great Mogul Emperor of India, the famous patron of religions, arts, and sciences, the most liberal of all the Mussulman sovereigns. There has never been a more tolerant or enlightened ruler than the Emperor Akbar, either in India or in any other Mahometan country.

- H.P. Blavatsky, Theosophical Glossary, (1892)

- The compassionate heart of his majesty finds no pleasure in cruelties or in causing sorrow to others; he is ever sparing of the lives of his subjects, wishing to bestow happiness upon all.

- Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl. quoted from Lal, K. S. (1999). Theory and practice of Muslim state in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 2

- The king, in his wisdom, understood the spirit of the age, and shaped his plans accordingly.

- Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl. quoted from Lal, K. S. (1992). The legacy of Muslim rule in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 3

- Like a good Turk he had no effeminate distaste for human blood; when, at the age of fourteen, he was invited to win the title of Ghazi—Slayer of the Infidel—by killing a Hindu prisoner, he cut off the man’s head at once with one stroke of his scimitar. These were the barbarous beginnings of a man destined to become one of the wisest, most humane and most cultured of all the kings known to history.

- Will Durant Our Oriental Heritage. Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- Both law and taxation were severe, but far less than before. From one-sixth to one-third of the gross produce of the soil was taken from the peasants, amounting to some $100,000,000 a year in land tax. The Emperor was legislator, executive and judge; as supreme court he spent many hours in giving audience to important litigants. His law forbade child marriage and compulsory suttee, sanctioned the remarriage of widows, abolished the slavery of captives and the slaughter of animals for sacrifice, gave freedom to all religions, opened career to every talent of whatever creed or race, and removed the head-tax that the Afghan rulers had placed upon all Hindus unconverted to Islam.91 At the beginning of his reign the law included such punishments as mutilation; at the end it was probably the most enlightened code of any sixteenth-century government. Every state begins with violence, and (if it becomes secure) mellows into liberty.

- Will Durant Our Oriental Heritage. Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- While Catholics were murdering Protestants in France, and Protestants, under Elizabeth, were murdering Catholics in England, and the Inquisition was killing and robbing Jews in Spain, and Bruno was being burned at the stake in Italy, Akbar invited the representatives of all the religions in his empire to a conference, pledged them to peace, issued edicts of toleration for every cult and creed, and, as evidence of his own neutrality, married wives from the Brahman, Buddhist, and Mohammedan faiths.

His greatest pleasure, after the fires of youth had cooled, was in the free discussion of religious beliefs. … The King took no stock in revelations, and would accept nothing that could not justify itself with science and philosophy. It was not unusual for him to gather friends and prelates of various sects together, and discuss religion with them from Thursday evening to Friday noon. When the Moslem mullahs and the Christian priests quarreled he reproved them both, saying that God should be worshiped through the intellect, and not by a blind adherence to supposed revelations. "Each person," he said, in the spirit — and perhaps through the influence — of the Upanishads and Kabir, "according to his condition gives the Supreme Being a name; but in reality to name the Unknowable is vain."- Will Durant Our Oriental Heritage. Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- Harassed by the religious divisions in his kingdom, and disturbed by the thought that they might disrupt it after his death, Akbar finally decided to promulgate a new religion, containing in simple form the essentials of the warring faiths... The Council perforce consenting, he issued a decree proclaiming himself the infallible head of the church; this was the chief contribution of Christianity to the new religion. The creed was a pantheistic monotheism in the best Hindu tradition, with a spark of sun and fire worship from the Zoroastrians, and a semi-Jain recommendation to abstain from meat. The slaughter of cows was made a capital offense: nothing could have pleased the Hindus more, or the Moslems less. A later edict made vegetarianism compulsory on the entire population for at least a hundred days in the year; and in further consideration of native ideas, garlic and onions were prohibited. The building of mosques, the fast of Ramadan, the pilgrimage to Mecca, and other Mohammedan customs were banned. Many Moslems who resisted the edicts were exiled.108 In the center of the Peace Court at Fathpur-Sikri a Temple of United Religion was built (and still stands there) as a symbol of the Emperor’s fond hope that now all the inhabitants of India might be brothers, worshiping the same God. As a religion the Din Ilahi never succeeded; Akbar found tradition too strong for his infallibility. A few thousand rallied to the new cult, largely as a means of securing official favor; the vast majority adhered to their inherited gods. Politically the stroke had some beneficent results. The abolition of the head-tax and the pilgrim-tax on the Hindus, the freedom granted to all religions,XV the weakening of racial and religious fanaticism, dogmatism and division, far outweighed the egotism and excesses of Akbar’s novel revelation. And it won him such loyalty from even the Hindus who did not accept his creed that his prime purpose—political unity—was largely achieved.

- Will Durant Our Oriental Heritage. Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- With his own fellow Moslems, however, the Din Ilahi was a source of bitter resentment, leading at one time to open revolt, and stirring Prince Jehangir into treacherous machinations against his father. The Prince complained that Akbar had reigned forty years, and had so strong a constitution that there was no prospect of his early death. Jehangir organized an army of thirty thousand horsemen, killed Abu-1 Fazl, the King’s court historian and dearest friend, and proclaimed himself emperor. Akbar persuaded the youth to submit, and forgave him after a day; but the disloyalty of his son, added to the death of his mother and his friend, broke his spirit, and left him an easy prey for the Great Enemy. In his last days his children ignored him, and gave their energies to quarreling for his throne. Only a few intimates were with him when he died—presumably of dysentery, perhaps of poisoning by Jehangir. Mullahs came to his deathbed to reconvert him to Islam, but they failed; the King “passed away without the benefit of the prayers of any church or sect.”109 No crowd followed his simple funeral; and the sons and courtiers who had worn mourning for the event discarded it the same evening, and rejoiced that they had inherited his kingdom. It was a bitter death for the justest and wisest ruler that Asia has ever known.

- Will Durant Our Oriental Heritage. Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- To most Hindus Akbar is one of the greatest of the Muslim emperors of India and Aurangzeb one of the worst; to many Muslims the opposite is the case. To an outsider there can be little doubt that Akbar's way was the right one. . . . Akbar disrupted the Muslim community by recognizing that India is not an Islamic country: Aurangzeb disrupted India by behaving as though it were.

- Gascoigne, Bamber. The Great Moghuls. London, 1976. 227, in Ibn Warraq, Why I am not a muslim, 1995. p 224

- It is highly doubtful if the Mughal period deserves the credit it has been given as a period of religious tolerance. Akbar is now known only for his policy of sulh-i-kul, at least among the learned Hindus. It is no more remembered that to start with he was also a pious Muslim who had viewed as jihãd his sack of Chittor. Nor is it understood by the learned Hindus that his policy of sulh-i-kul was motivated mainly by his bid to free himself from the stranglehold of the orthodox ‘Ulamã, and that any benefit which Hindus derived from it was no more than a by-product. Akbar never failed to demand daughters of the Rajput kings for his harem. Moreover, as our citations show, he was not able to control the religious zeal of his functionaries at the lower levels so far as Hindu temples were concerned. ... The reversal of Akbar’s policy thus started by his two immediate successors reached its apotheosis in the reign of Aurangzeb, the paragon of Islamic piety in the minds of India’s Muslims. What is more significant, Akbar has never been forgiven by those who have regarded themselves as custodians of Islam, right upto our own times; Maulana Abul Kalam Azad is a typical example. In any case one swallow has never made a summer.

- Goel, S. R. et al. (1993). Hindu temples : what happened to them.

- This hall was, by order of the Emperor Jehanguire, the son of Acbar, highly decorated with painting and gilding; but in the lapse of time it was found to be gone greatly to decay; and the Emperor Aurungzebe, either from superstition or avarice, ordered it to be entirely defaced, and the walls whitened.

- About the defaced tomb of Akbar. William Hodges, Travels in India during the Years 1780, 1781, 1782 and 1783.

- Akbar's liberalism can be adjudged from another fact, namely that he issued gold and silver coins bearing the figures of Rama and Sita and inscribed with the legend Rama Siya.

- Lal, B. B. (2008). Rāma, his historicity, mandir, and setu: Evidence of literature, archaeology, and other sciences. New Delhi: Aryan Books International. p.6

- Akbar had prohibited enslavement and sale of women and children of peasants who had defaulted in payment of revenue. He knew, as Abul Fazl says, that many evil hearted and vicious men either because of ill-founded suspicion or sheer greed, used to proceed to villages and mahals and sack them.

- Lal, K. S. (2012). Indian muslims: Who are they.

- The first revolutionary step of Akbar was the abolition of the Jiziyah, the hated discriminatory tax paid by Hindu Zimmis. The Hindus, as Zimmis, had become second class citizens in their own homeland and were suffered to live under certain disabilities.

- Lal, K. S. (1999). Theory and practice of Muslim state in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 2

- Akbar’s court was essentially foreign, and even in his later years the Indian element, whether Hindu or Moslem, constituted only a small proportion of the whole.

- Moreland, India at the Death of Akbar, quoted from Lal, K. S. (1994). Muslim slave system in medieval India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 10

- "At the religious discussion meetings held by Akbar, 'at which every one... might say or ask what he liked,' the emperor examined people about the creation of the Quran, elicited their belief, or otherwise, in revelation, and raised doubts in them regarding all things connected with the Prophet and the imams. He distinctly denied the existence of Jins, of angels, and of all other beings of the invisible world, as well as the miracles of the Prophet."

- Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh by Abdul Qadir Badaoni, vol. II, quoted from Lal, K. S. (1999). Theory and practice of Muslim state in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 2

- [The people also got busy collecting] "all kinds of exploded errors, and brought them to his Majesty, as if they were so many presents... Every doctrine and command of Islam as the prophetship, the harmony of Islam with reason... the details of the day of resurrection and judgement, all were doubted and ridiculed."

- Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh by Abdul Qadir Badaoni, vol. II, p. 307. quoted from Lal, K. S. (1999). Theory and practice of Muslim state in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 2

- [Brahmans] surpass other learned men in their treatises on morals....His Majesty, on hearing… how much the people of the country prized their institutions, commenced to look upon them with affection.

- Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh by Abdul Qadir Badaoni, vol. II, quoted from Lal, K. S. (1992). The legacy of Muslim rule in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Akbar was the first emperor to abolish Jizyah with one stroke of pen, along with all its associations and implications, including the distinction of Muslim and Dhimmî into the bargain. His son and grandson followed his example in regard to Jizyah, generally speaking, but reimposed upon the Hindus all the other restrictions and disabilities suffered by them before.

- Harsh Narain, Jizyah and the spread of Islam, chapter 3

- The same spirit of intolerance was shown by the Jesuit fathers in the Moghul court. The Emperor Akbar took great interest in religious discussions and summoned to the court scholarly Jesuit missionaries from Goa. They were received with great courtesy, but the free discussions in the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship), where the debates on religion took place, displeased the Jesuit fathers greatly. Their intolerance of other religions and their arrogant attitude towards the exponents of other faiths were unwelcome also to the Emperor. So the missionaries had to leave the capital greatly disappointed.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1953). Asia and Western dominance, a survey of the Vasco da Gama epoch of Asian history, 1498-1945, by K.M. Panikkar. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

- [Akbar is reported to have said:] “My dear child… with all of God’s creatures, I am at peace; why should I permit myself, under any consideration, to be the cause of molestation or aggression to any one? Besides, are not five parts in six of mankind either Hindus or aliens to the faith; and were I to be governed by motives of the kind suggested in your inquiry, what alternative can I have but to put them all to death? I have thought it therefore my wisest plan to let these men alone.”

- Tarikh-i-Salim Shahi (Calcutta Edition), pp. 21-22. (Some scholars hold that this work is a fabrication and does not comprise the real Memoirs of Jahangir) quoted from Lal, K. S. (1990). Indian muslims: Who are they.

- Islam, like the other two religions of the Judaic family, is exclusive-minded and intolerant by comparison with the religions and philosophies of Indian origin. Yet the influence of India on Akbar went so deep that he was characteristically Indian in (his) large-hearted catholicity.

- A. J. Toynbee, One World and India, p. 19. quoted from Lal, K. S. (1999). Theory and practice of Muslim state in India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 2

- With Islamic zeal, Akbar at first persecuted the Hindus.

- Yogananda, P., . Autobiography of a Yogi. S.I.: Duke Classics. Ch.21

- It is significant and ironic that the most tolerant of all the Muslim rulers in the history of India was also the one who moved farthest away from orthodox Islam and, in the end, rejected it for an eclectic religion of his own devising... Akbar's driving principle was universal toleration, and all the Hindus, Christians, Jains, and Parsees enjoyed full liberty of conscience and of public worship. He married Hindu princesses, abolished pilgrim dues, and employed Hindus in high office. The Hindu princesses were even allowed to practice their own religious rites inside the palace. "No pressure was put on the princes of Amber, Marwar, or Bikaner to adopt Islam, and they were freely entrusted with the highest military commands and the most responsible administrative offices. That was an entirely new departure, due to Akbar himself."

- Ibn Warraq, Why I am not a muslim, 1995. p 223

- Professor Mubarak Ali, a respected historian living in Lahore, asserts that Akbar has been systematically eliminated from most textbooks in Pakistan in order to "divert attention away from his 'misplaced' policies". Where they exist, discussions of Akbar are short and superficial...

- M Ali cited by : Y. Rosser, Islamization of Pakistani Social Studies Textbooks, 2003

- Although the Mughal emperor Akbar attempted to prohibit the practice of enslaving conquered Hindus, his efforts were only temporarily successful.43 According to one early seventeenth-century account, 'Abd Allah Khan Firuz Jang, an Uzbek noble at the Mughal court during the 1620s and 1630s, was appointed to the position of governor of the regions of Kalpi and Kher and, in the process of subjugating the local rebels, "beheaded the leaders and enslaved their women, daughters and children, who were more than 2 lacks [200,000] in number".

- Hindus beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade Author(s): Scott C. Levi Source: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Third Series, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Nov., 2002), pp. 277-288

Quotes about Akbar's military campaigns

- “On the 1st Rajab 990 [AD 1582] he (Husain Qulî Khãn) encamped by a field of maize near NagarkoT. The fortress (hissãr) of Bhîm, which is an idol temple of Mahãmãî, and in which none but her servants dwelt, was taken by the valour of the assailants at the first assault. A party of Rajpûts, who had resolved to die, fought most desperately till they were all cut down. A number of Brãhmans who for many years had served the temple, never gave one thought to flight, and were killed. Nearly 200 black cows belonging to Hindûs had, during the struggle, crowded together for shelter in the temple. Some savage Turks, while the arrows and bullets were falling like rain, killed those cows. They then took off their boots and filled them with the blood and cast it upon the roof and walls of the temple.”173

- Tabqãt-i-Akharî by Nizamuddin Ahmad. Jalãlu’d-Dîn Muhammad Akbar Pãdshãh Ghãzî (AD 1556-1605) Nagarkot Kangra (Himachal Pradesh)

- “…The temple of Nagarkot, which is outside the city, was taken at the very outset… On this occasion many mountaineers became food for the flashing sword. And that golden umbrella, which was erected on the top of the cupola of the temple, they riddled with arrows… And black cows, to the number of 200, to which they pay boundless respect, and actually worship, and present to the temple, which they look upon as an asylum, and let loose there, were killed by the Musulmans. And, while arrows and bullets were continually falling like drops of rain, through their zeal and excessive hatred of idolatry they filled their shoes full of blood and threw it on the doors and walls of the temple… the army of Husain Quli Khan was suffering great hardships. For these reasons he concluded a treaty with them… and having put all things straight he built the cupola of a lofty mosque over the gateway of Rajah Jai Chand.”

- `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni, Muntkhab-ut-Tawarikh. Jalalu’d-Din Muhammad Akbar Padshah Ghazi (AD 1556-1605). Muntkhab-ut-Tawarikh. Nagarkot Kangra (Himachal Pradesh)

- “In this year on the dismissal of Husain Khan the Emperor gave the pargana of Lak’hnou as jagir to Mahdi Qasim Khan… Husain Khan was exceedingly indignant with Mahdi Qasim Khan on account of this… After a time he left her in helplessness, and the daughter of Mahdi Qasim Bêg at Khairabad with her brothers, and set off from Lak’hnou with the intention of carrying on a religious war, and of breaking the idols and destroying the idol-temples. He had heard that the bricks of these were of silver and gold, and conceiving a desire for this and all the other abundant and unlimited treasures, of which he had heard a lying report, he set out by way of Oudh to the Siwalik mountains…”

- `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni, Muntkhab-ut-Tawarikh. Jalalu’d-Din Muhammad Akbar Padshah Ghazi (AD 1556-1605) Siwalik (Uttar Pradesh)

- When Mewar was invaded [AD 1600] many temples were demolished by the invading Mughal army [led by Prince Salîm].

- Jalãlu’d-Dîn Muhammad Akbar Pãdshãh Ghãzî (AD 1556-1605) Mewar (Rajasthan) . Zubdatu’t-Tawãrîkh, Shaykh Nãru’l-Haqq al-Mashriqî al-Dihlivî al-Bukhãrî, Tãrîkh-i-Haqqî (of which Zubdatu’t-Tawãrîkh is an extension) cited by Sharma Sri Ram. 1988. The Religious Policy of the Mughal Emperors. 3rd ed. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.,, p. 62.

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.