Zaporizhzhia

City and administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

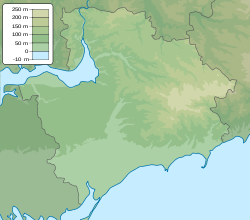

Zaporizhzhia,[1][note 1] formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921,[note 2] is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast.[2] Zaporizhzhia has a population of 710,052 (2022 estimate).[3]

Zaporizhzhia

Запоріжжя | |

|---|---|

| Ukrainian transcription(s) | |

| • National/"BGN/PCGN" | Zaporizhzhia |

| • ALA-LC | Zaporiz͡hz͡hi͡a |

| • Scholarly | Zaporižžja |

From top to bottom and left to right:

| |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 47°51′00″N 35°07′03″E | |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Oblast | Zaporizhzhia Oblast |

| Raion | Zaporizhzhia Raion |

| Hromada | Zaporizhzhia urban hromada |

| Founded | 1770 |

| City rights | 1806 |

| Raions | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rehina Kharchenko |

| Area | |

| 334 km2 (129 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 4,675 km2 (1,805 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

| 710,052 | |

| • Density | 1,365.2/km2 (3,536/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 840,866 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 69xxx |

| Area code | +380 61(2) |

| Climate | Dfa |

| |

Zaporizhzhia is known for the historic island of Khortytsia, multiple power stations and for being an important industrial centre. Steel, aluminium, aircraft engines, automobiles, transformers for substations, and other heavy industrial goods are produced in the region.

Names and etymology

The name Zaporizhzhia refers to the position of the city: "beyond the rapids"—downstream or south of the Dnieper Rapids. These were previously an impediment to navigation and the site of important portages. In 1932, the rapids were flooded to become part of the reservoir of the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station.[4]

Before 1921, the city was called Aleksandrovsk (or Oleksandrivsk), named after the original fortress that formed a part of the Dnieper Defence Line of the Russian Empire.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Zaporizhzhia was founded in 1770, when the Aleksandrovskaya (Александровская) Fortress was built as a part of the Dnieper Defence Line, to protect the southern territories of the Russian Empire from Crimean Tatar invasions.[5] Following the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1775, the southern lands of the Russian Plain and the Crimean peninsula were absorbed into the Russian Empire. The Aleksandrovskaya Fortress then lost its military significance, and became a small rural town, which from 1806 to around 1930 was called Alexandrovsk.[4]

The opening of the Kichkas Bridge at the start of the 20th century, the first rail crossing of the Dnieper, was followed by the industrial growth of Zaporizhzhia.[6] In 1916, during World War I, the DEKA Stock Association transferred its aircraft engine manufacturing plant from Saint Petersburg to Zaporizhzhia.[7]

During the Russian Civil War (1918–1921), Zaporizhzhia was the scene of fierce fighting between the Red Army and the White armies of Denikin and Wrangel, Petliura's Ukrainian People's Army of the Ukrainian People's Republic, and German-Austrian troops. The opposing armies used the strategically important Kichkas Bridge to transfer troops, ammunition, and medical supplies. The Soviet government industrialized Zaporizhzhia still further during the 1920s and 1930s, when the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station, and the Zaporizhzhia Steel Plant, and the Dnieper Aluminium Plant were built.[8][9][10] In the 1930s, the American United Engineering and Foundry Company built a strip mill similar to the Ford River Rouge steel mill to produce rolling steel strip. The annual capacity of the mill reached 540,000 tonnes (600,000 short tons) of 170 cm (66 inches) wide steel.[11]

World War II (1941–1945)

After the outbreak of the War between the USSR and Nazi Germany in June 1941, the Soviet government began evacuating Zaporizhzhia's industries to Siberia.[12] and the Soviet security forces began shooting political prisoners in the city.[13] On 18 August 1941, elements of the German 1st Panzergruppe reached the outskirts of Zaporizhzhia on the right bank and seized the island of Khortytsia.[14]

The Red Army blew a 120 by 10 metres (394 ft × 33 ft) hole in the Dnieper hydroelectric dam on 18 August 1941, producing a flood wave that swept from Zaporizhzhia to Nikopol.[12] The flood killed local residents as well as soldiers from both armies, with historians estimating a death toll between 20,000 and 100,000.[15] Despite reinforcements, Zaporizhzhia was taken on 3 October 1941.[16] The German occupation lasted two years; during which the Germans shot over 35,000 people, and sent 58,000 people to Germany as forced labourers.[12]

The Germans reformed Army Group South in February 1943, and put its headquarters in Zaporizhzhia.[17] Adolf Hitler visited the headquarters in February 1943, and again the following month, where he was briefed by Field Marshal Eric von Manstein and his air force counterpart Field Marshal Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, and in September 1943,[18] the month the Army Group moved its headquarters to Kirovohrad.[19]

In August 1943, the Germans built the Panther-Wotan defence line along the Dnieper from Kyiv to Crimea. They retreated back to this line in September 1943, holding the city as a bridgehead over the Dnieper with elements of 40th Panzer and 17th Corps.[20] The Soviet Southwestern Front, commanded by Army General Rodion Malinovsky, attacked Zaporizhzhia on 10 October 1943.[20] The defenders repelled these attacks, but the Red Army launched a surprise night attack on 13 October, which succeeded in reclaiming most parts of the city.[21]

1991–present

In 2004, to alleviate congestion around the Zaporizhzhia Arch Bridge area, construction began on the New Zaporizhzhia Dniper Bridge, although construction was halted soon after it began, due to a lack of funding.[22]

Russo-Ukrainian War

During the 2014 Euromaidan regional state administration occupations, during protests against President Viktor Yanukovych,[23] Zaporizhzhia's regional state administration building was occupied by 4,500 protesters,[24] and there were clashes between Ukrainian and pro-Russian activists in April 2014.[25]

On 19 May 2016, the Verkhovna Rada approved the "Decommunisation Law".[26] Since the introduction of the law, the Zaporizhzhia City Council has renamed over 50 streets and administrative areas of the city,[note 3] monuments of the Soviet Union leaders Lenin and Felix Dzerzhinsky have been destroyed,[27][28] and names honouring Soviet leaders in the titles of industrial plants, factories, culture centres, and the DniproHES have been removed.[29]

Russian invasion (2022)

Russian forces have been engaged in ongoing attacks on Zaporizhzhia since the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. On 27 February, fighting was reported in the southern outskirts,[30] and Russian forces began shelling the city later that evening.[31] Russia invaded and occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast but failed to take Zaporizhzhia itself. On 3 March, Russian forces approached the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, raising concerns about a potential nuclear meltdown.[32][33] Russian military forces fired missiles on Zaporizhzhia on the evening of 12/13 May.[34]

On 30 September, hours before Russia formally annexed Southern and Eastern Ukraine, the Russian Armed Forces launched S-300 missiles at a civilian convoy in Zaporizhzhia, killing at least 30 people.[35] On 9 October, Russian forces launched rockets at residential buildings, killing at least 17 people.[36]

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

Zaporizhzhia is located in south-eastern Ukraine. The Dnieper splits the city in two; between them is Khortytsia Island. The city covers 334 km2 (129 sq mi) at an elevation of 50 m (160 ft) above sea level.[37] The New and Old Dnieper flow past around Khortytsia: The New Dnieper is about 800 m (2,600 feet) wide while the Old Dnieper is about 200 m (660 feet) wide. The island size is 12 km × 2 km (7.5 mi × 1.2 mi). Smaller rivers in the city also enter the Dnieper: Sukha and Mokra Moskovka, Kushuhum, and Verkhnia Khortytsia.

The flora of Khortytsia is unique and diverse, due to the dry steppe air and a large freshwater basin, which cleans the air polluted by industry. The island is a national park. The ground surface is cut by large ravines ("balka"), hiking routes and historical monuments. The island, which is a popular recreational area, has sanatoriums, resorts, health centres, and sandy beaches.[38]

Climate

| Climate data for Zaporizhzhia (1991–2020, extremes 1959–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.3 (−20.7) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−25 (−13) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−2 (28) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−3 (27) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−26.2 (−15.2) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

37 (1.5) |

41 (1.6) |

51 (2.0) |

61 (2.4) |

45 (1.8) |

44 (1.7) |

38 (1.5) |

34 (1.3) |

40 (1.6) |

53 (2.1) |

515 (20.3) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 7 (2.8) |

8 (3.1) |

4 (1.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

8 (3.1) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 130 |

| Average snowy days | 14 | 14 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 58 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.8 | 82.6 | 76.3 | 66.5 | 64.3 | 64.5 | 62.5 | 60.6 | 67.6 | 76.6 | 83.9 | 86.5 | 73.1 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[39] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity 1991–2020)[40] | |||||||||||||

Governance

Zaporizhzhia is the main city of Zaporizhzhia Oblast with a form of self-rule within the oblast. The city is divided into 7 urban districts.

|

|

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

City population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 18,849 | — |

| 1926 | 55,260 | +193.2% |

| 1939 | 289,280 | +423.5% |

| 1959 | 434,638 | +50.2% |

| 1970 | 657,890 | +51.4% |

| 1979 | 780,745 | +18.7% |

| 1989 | 883,909 | +13.2% |

| 2001 | 815,256 | −7.8% |

| 2011 | 776,535 | −4.7% |

| 2022 | 710,052 | −8.6% |

| Source: [42] | ||

The city population has been declining since the first years of state independence. In 2014–2015 the rate of the population decrease was −0.56%/year.[43]

In January 2017, the population was 750,685.[44] The total reduction of the population of the city since independence has been around 146,000 (not including 2017–2018).

|

|

|

Ethnic structure

According to the 2001 census,[68] 70.28% of the population of Zaporizhzhia (total population 815,300) were Ukrainians, 25.39% were Russians, 0.67% were Belarusians, 0.44% were Bulgarians, 0.42% were Jews, 0.38% were Georgians, 0.38% were Armenians, 0.27% were Tatar, 0.15% were Azeris, 0.11% were Roma (Gypsies), 0.1% were Poles, 0.09% were Germans, 0.09% were Moldovans, and 0.07% were Greeks.

Language

Ukrainian is used for official government business. The native language of people living in Zaporizhzhia, according to censuses in Ukraine (by percent):

Religion

The following religious denominations are present in Zaporizhzhia:[73]

- Christianity

- Orthodoxy

Most of the citizens are Orthodox Christians of Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) or Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Among the Orthodox churches the Church of the Intercession, which is under the Moscow Patriarchate, is most popular. There are also St. Nicholas Church and St. Andrew's Cathedral in the city.

- Protestantism

Protestantism is represented by:

- All-Ukrainian Union of Christians of Evangelical Faith;

- Seventh-day Adventist Church;

- Full Gospel Church.

- Catholicism

Catholicism is represented by:

The biggest Catholic church is Church of God, the Father of Mercy

- Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is represented by one union and six communities.

- Islam

In the Zaporizhzhia district there are five communities which are part of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Ukraine and four independent Muslim communities.

- Hinduism

The city hosts a branch of the Vedic Academy.

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

Industry

Zaporizhzhia is an important industrial centre of Ukraine, the country's main car manufacturing company, the Motor-Sich aircraft engine manufacturer. Well supplied with electricity, Zaporizhzhia forms, together with the adjoining Donets Basin (Donbas) and the Nikopol manganese and Kryvyi Rih iron mines, one of Ukraine's leading industrial complexes.

The city is a home of Ukraine's main automobile production centre, which is based at the Zaporizhzhia Automobile Factory (ZAZ), producing Ukrainian car brands such as Zaporozhets and Tavria.

After the end of the Russian Revolution, the city became an important industrial centre. The presence of cheap labor and the proximity of deposits of coal, iron ore, and manganese created favorable conditions for large-scale enterprises of the iron and mechanical engineering industries. Today Zaporizhzhia is an important industrial centre of the region with heavy industry (particularly metallurgy), aluminium, and chemical industry. Cars, avia motors and radioelectronics are manufactured in the city. The port of Zaporizhzhia is important for transshipment for goods from the Donbas.

Zaporizhstal, Ukraine's fourth largest steel maker, and ranking 54th in the world, is based in the city.

Electricity generation

Zaporizhzhia is a large electricity generating hub. There are hydroelectric power plant known as "DniproHES" Dnieper Hydroelectric Station and the largest nuclear power plant in Europe. Prior to the 2022 invasion, the plants generated about 25% of the Ukrainian electricity supply. Located near Enerhodar and about 60 km (37 miles) from Zaporizhzhia is the Zaporizhzhia thermal power station and the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear power plant in Europe.

Culture

Zaporizhzhia has an orchestra, museums, theatres, and libraries. These include the Magara Academic Drama Theatre, the Municipal Theatre Lab "VIE", the Theatre for Young-Age spectators, the Theatre of Horse Riding "Zaporizhzhian Cossacks", the Zaporizhzhia Regional Museum, the National Museum of the History of the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, the Zaporizhzhia Regional Art Museum, the Motor Sich Aviation Museum, and the Zaporizhzhia Region Universal Scientific Library.

There are a number of small amateur groups of folk music bands, art galleries in Zaporizhzhia. The city regularly holds festivals, Cossack martial arts competitions, and art exhibitions.

Zaporizhzhia has an open-air exhibition-and-sale of Zaporizhzhia city association of artists «Kolorit» near the 'Fountain of Life' at the Mayakovskoho square. A daily exhibition of artists' organizations of the city is a unique place in Zaporizhzhia, where people can meet craftsmen and artists, watch carving, embroidery, beading classes, and receive advice from professional artists and designers.

Main sights

The historical and cultural museum "Zaporizka Sich" is placed on the northern rocky part of Khotritsa Island. The museum is a reconstruction of the stronghold of the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, and contains features of the military camp life and their lifestyle.

Each of the smaller islands between the dam and the island Khortytsia has its own legend. On one of them, Durnya Scala ("Rock of the Fool"), Tzar Peter the Great flogged the Cossacks for their betrayal of the Russians during the Great Northern War between Russia and Sweden. Another small island, Stolb ("Pillar"), has a geological feature, which looks like a large bowl in granite slabs, the Cossack's Bowl. It is said that in summer days, water can be boiled in this "bowl", and the Cossacks used it for cooking galushki (boiled dough in a spicy broth).[75]

Transport links

Summarize

Perspective

Zaporizhzhia is an important transportation hub in Ukraine that includes roads, as well as rail, river and air links for passenger and freight transport. Zaporizhzhia International Airport, located to the east of the city on the left-bank of the Dnieper, serves domestic and international flights. Shyroke Airfield is to the west of the city on the right-bank of the Dnieper.

Zaporizhzhia is bypassed beyond its eastern outskirts by a major national highway M18, which connects Kharkiv with Simferopol. The H08, which starts just outside Kyiv and travels southeast along the Dnieper through Kremenchuk, Kamianske, Dnipro, passes through Zaporizhzhia on the way to Mariupol. The H15 from Donetsk and the H23 from Kropyvnytskyi via Kryvyi Rih, both end in Zaporizhzhia.

There are four road bridges and two rail bridges over the Dnieper, nearly all of which bridges cross Khortytsia Island. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy opened the first stage of the New Zaporizhzhia Dniper Bridge early in 2022.

The city has two rail stations, Zaporizhzhia-1 railway station and Zaporizhzhia-the-Second. The First is the central station, located in the southern part of the city and is a part of Simferopol-Kharkiv, the "north-south" transit route. The line of the Zaporizhzhia-the-Second station connects the Donbas coalfield with Kryvyi Rih. The city has an extensive tram network with 7 lines called the Zaporizhzhia Tram.

The city's two river ports are part of the national water transportation infrastructure that connects Kyiv to Kherson along the Dnieper. Freight ships and cutter boats travel between Zaporizhzhia and nearby villages. The island of Khortytsia splits the Dnieper into two; the main channel passes the island on its eastern side, with the Staryi Dnipro (Old Dnieper) flowing past the island on the western side.

Sports

The mmain association football club of the city is FC Metalurh Zaporizhzhia, whose home ground is Slavutych-Arena.

Notable people

- Alyosha (born 1986), Ukrainian singer, stage name of Olena Oleksandrivna Kucher

- Anzhelika Bielova (born 1995), Ukrainian activist of Romani origin[76]

- Vasiliy Bebko, (1932–2022), Russian diplomat

- Tamara Bulat (1933–2004), Ukrainian-American musicologist

- Victoria Bulitko (born 1983), a Ukrainian film, TV and theatre actress.

- Evgeniy Chernyak (born 1969), Ukrainian businessman

- Evgeniy Chuikov (1924–2000) Ukrainian landscape painter working in the Russian realist and French Impressionist traditions.

- Volodymyr Dakhno (1932–2006) Ukrainian animator and animation film director.

- Valentyna Danishevska (born 1957), Ukrainian lawyer and judge

- Gerhard Ens (1863–1952), farmer, immigration agent and politician in Saskatchewan

- Igor Fesunenko (1933–2016), Russian journalist and foreign affairs writer

- Arkady Gendler (1921–2017), Yiddish singer

- Sergey Glazyev (born 1961), Russian politician and economist

- Alina Gorlova (born 1992), a Ukrainian filmmaker, director, and screenwriter

- Konstantin Grigorishin (born 1965), a Russian-Ukrainian businessman and billionaire.

- Volodymyr Horbulin (born 1939), Ukrainian politician

- Valeriy Ivaschenko (born 1956), Ukrainian former Deputy Minister of Defence

- Boris Ivchenko, (1941–1990) Ukrainian actor and film director

- Igor P. Kaidashev (born 1969), Ukrainian immunologist and allergist

- Valeriy Kostyuk (born 1940), Russian scientist

- Maxim Ksenzov (born 1973), Russian statesman

- Valery Kulikov (born 1956), Ukrainian-born Russian politician

- Gosha Kutsenko (born 1967), Russian actor, producer, singer, poet and screenwriter

- Arsen Mirzoyan (born 1978), Ukrainian singer and songwriter

- Valentyn Nalyvaichenko (born 1966), Ukrainian diplomat and politician.

- Eva Neymann (born 1974), Ukrainian film director

- Maria Nikiforova (1885–1919), revolutionary insurgent and Anarchist partisan leader.

- Anna October (born 1991), Ukrainian fashion designer

- Aleksandr Panayotov (born 1984), Russian-Ukrainian singer and songwriter

- Mykhailo Papiyev (born 1960), Ukrainian engineer and politician

- Oleksandr Peklushenko, (1954–2015) Ukrainian politician

- Max Polyakov (born 1977), an international technology entrepreneur, economist and philanthropist

- Georgy Shchokin (born 1954), businessman, sociologist, psychologist and politician

- Boris Shtein, (1892–1961) Soviet diplomat

- Oleksandr Sin (born 1961), Ukrainian politician former mayor of Zaporizhzhia

- Serhiy Sobolyev (born 1961), Ukrainian politician

- Yanina Sokolova (born 1984) a journalist, TV presenter and actress.

- Naum Sorkin, (1899–1980) a Soviet military officer and diplomat.

- Oleksandr Starukh (born 1973), Ukrainian historian and politician

- Liudmyla Suprun (born 1965), a Ukrainian politician

- Yevhen Synelnykov (born 1981), a Ukrainian TV presenter, director and actor

- Estas Tonne (born 1975), a musician, plays guitar and flute

- Vladyslav Yama (born 1982), a Ukrainian dancer and educator

- Maksym Ostapenko (born 1971), Ukrainian scientist, archaeologist, cultural activist, and a soldier

- Vlad Savchenko (born 1991), film producer and public activist

Sport

- Polina Astakhova (1936–2005) an artistic gymnast; won ten medals at the 1956, 1960 and 1964 Summer Olympics.

- Anastasia Bliznyuk (born 1994), a Russian group rhythmic gymnast.

- Maksym Dolhov (born 1996), Ukrainian diver

- Yan Kovalevskyi (born 1993), Ukrainian footballer

- Tanja Logwin (born 1974), Ukrainian-born Austrian handball player

- Alina Maksymenko (born 1991), Ukrainian rhythmic gymnast

- Oleksii Pashkov (born 1981), silver medallist in the discus at the 2012 Summer Paralympics

- Volodymyr Polikarpenko (born 1972), Ukrainian former trialthon athlete

- Yakiv Punkin (1921–1994) wrestler, gold medallist at the 1952 Summer Olympics.

- Oksana Skaldina (born 1972) gymnast; bronze medallist at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Ganna Sorokina (born 1976) diver; team bronze medallist at the 2000 Summer Olympics

- Olga Strazheva (born 1972) gymnast; team gold medallist at the 1988 Summer Olympics

- Vita Styopina (born 1976) high jumper; bronze medallist at the 2004 Summer Olympics

- Denys Sylantyev (born 1976) politician and swimmer; four time Olympian, silver medallist at the 2000 Summer Olympics and national flag bearer at the 2004 Summer Olympics.

- Razmik Tonoyan (born 1988), Ukrainian sambist, (a Soviet-origin Russian martial art)

- Roman Volod'kov (born 1973), Ukrainian former diver

- Sergiusz Wołczaniecki (born 1964) a Polish weightlifter; bronze medallist at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Olena Zhupina (born 1973), Ukrainian diver

In popular culture

Zaporizhzhia is a setting in two Axis victory in World War II short novels by the American author Harry Turtledove, Ready for the Fatherland (1991) and The Phantom Tolbukhin (1998).

Twin towns – sister cities

Zaporizhzhia is twinned with:[77][78]

Lahti, Finland (1953)

Lahti, Finland (1953) Belfort, France (1967)

Belfort, France (1967) Birmingham, United Kingdom (1973)

Birmingham, United Kingdom (1973) Linz, Austria (1983)

Linz, Austria (1983) Oberhausen, Germany (1986)

Oberhausen, Germany (1986) Yichang, China (1997)

Yichang, China (1997) Magdeburg, Germany (2008)

Magdeburg, Germany (2008) Ashdod, Israel (2011)

Ashdod, Israel (2011) Steinbach, Canada (2018)

Steinbach, Canada (2018)

In 1969, the city renamed one of its streets after the city of Wrocław. The Wrocław authorities reciprocated, and a part of the Sudecka – Grabiszyńska Street towards the Square of the Silesian Insurgents was renamed Zaporoska Street.[79]

See also

Notes

- Ukrainian: Запоріжжя, IPA: [zɐpoˈriʒʲːɐ] ⓘ; Russian: Запорожье, romanized: Zaporozhye, IPA: [zəpɐˈroʐje] ⓘ; also spelled as Zaporizhzhya or Zaporizhia.

- Since modern Zaporizhiazhia was greatly enlarged in the Soviet Union, many typography in the city had to be renamed. In the year of the fall of the Russian Empire (1917), the population of Alexandrovsk was about 60,000 people. In the year of Ukraine's declaration of independence (1991), the city's population reached almost 1 million people.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.