William "Tiger" Dunlop

Military physician, businessman and politician in Upper Canada From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Dunlop (19 November 1792 – 29 June 1848) also known as Tiger Dunlop, was an army officer, surgeon, Canada Company official, author, justice of the peace, militia officer, politician, and office holder. He is notable for his contributions to the War of 1812 in Canada and his work in the Canada Company, helping to develop and populate a large part of Southern Ontario (the Huron Tract). He was later elected as a Member of Parliament for the Huron riding in the 1st Parliament of the Province of Canada, Canada West.

William "Tiger" Dunlop | |

|---|---|

William "Tiger" Dunlop | |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for Huron | |

| In office 1841–1846 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governors General | Lord Sydenham (1841) Charles Bagot (1842–1843) Sir Charles Metcalfe (1843–1845) Lord Cathcart (1845–1847) |

| Preceded by | James McGill Strachan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Dunlop November 17, 1792 Greenock, Scotland |

| Died | June 29, 1848 (aged 55) Côte-Saint-Paul, Montreal, Canada East |

| Resting place | Originally Hamilton, Canada West; later re-interred at Goderich, Canada West |

| Citizenship | British subject |

| Political party | Tory (moderate) |

| Parent(s) | Alexander Dunlop and Janet Graham |

| Relatives | Robert Graham Dunlop (brother) |

| Education | University of Glasgow |

| Occupation | Military physician, author, woodsman, soldier, politician |

| Profession | Physician |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army Upper Canada militia |

| Years of service | 1813–1828 (British Army) 1837–1838 (Upper Canada militia) |

| Rank | Assistant Surgeon (British Army); Lieutenant Colonel (Upper Canada militia) |

| Unit | 89th Regiment of Foot 1st Huron Regiment (militia) |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 Battle of Crysler's Farm Battle of Lundy's Lane |

Early life and education

Tiger Dunlop was born 19 November 1792 in Greenock, Scotland, the third son of a local banker Alexander Dunlop and Janet Graham. He pursued his medical studies at the University of Glasgow and in London.[1]

British Army

In January 1813 Dunlop joined the army as a hospital mate. A month later he was posted as an assistant surgeon in the 89th Regiment of Foot. He was first posted to the Isle of Wight, later leaving for Quebec in August 1813. He remained with the Army until 1828, although after the end of the Napoleonic Wars much of that time he was on half-pay and not serving.

From 1815 to 1820 Dunlop was in India, as a journalist and possibly other commercial activities. On returning to Britain, he taught medical jurisprudence at the University of Edinburgh, and also was in London.[1][2]

Life in Canada

Summarize

Perspective

War of 1812

The 89th Regiment left Britain on 4 February 1813, with Dunlop appointed assistant surgeon. The regiment was posted to Upper Canada during the War of 1812 in time to participate in the Battle of Crysler's Farm and the Battle of Lundy's Lane.

Like other war doctors, Dunlop was faced with seemingly impossible tasks. After the Battle of Chippawa, Dunlop worked alone on 220 men from both armies because no other surgeons were available. The story continues that Dunlop worked alone for more than two full days, barely sitting down and stopping only to eat and change clothes.[3] He played a more active role in the assault on Fort Erie on 15 August 1814, carrying about a dozen injured men out of the range of fire and providing survivors with basic necessities. He served with a road-cutting party near Penetanguishene in the spring of 1815.[2]

Dunlop subsequently wrote a book about his war-time experience in Canada, entitled Recollections of the American War of 1812–1814.

The Canada Company

In 1826, Dunlop moved to Upper Canada to work with John Galt and the Canada Company, settling in Goderich. The Canada Company had received a grant of management and settlement for the Huron Tract, a large tract of land to the south-west of Lake Huron. Galt, a Scottish novelist, had been appointed the director of the Company's affairs. Galt in turn appointed Dunlop as Warden of the Company's Woods and Forests by of the Canada Company. The position involved inspecting the company lands in the Huron Tract along the eastern shore of Lake Huron to protect them and the selection of land to be sold to settlers from Europe for profit. This position put Tiger Dunlop as second-in-command to Galt of the Company in Canada.

In 1829, Galt was recalled to England and dismissed for mismanagement, particularly incompetent bookkeeping.[4] As was the custom of the day, positions such as that held by Dunlop were personal appointments; he was in some danger of losing his position, but managed to keep it. In 1833 he was appointed the General Superintendent of the Huron Tract. It was at this time that Dunlop published Statistical Sketches of Upper Canada to encourage young people to come to Canada.[3]

Dunlop was present at the founding of Guelph, Ontario, the company headquarters for the Canada Company, and built his home north of Goderich.[2] A historic plaque in that city commemorates his assisting John Galt in helping to populate the Huron Tract.[5] The Company's achievement was later called "the most important single attempt at settlement in Canadian history".[6]

Dunlop left the Canada Company in 1838 because he refused to cease military activities as ordered by the Company.[1][7]

Rebellions of 1837

During the Rebellions of 1837, Dunlop formed and commanded the Huron Regiment in Upper Canada nicknamed The Bloody Useless.[1][7] The rebellion was short-lived and led by the radicals fighting for responsible government. The Huron Regiment consisted of approximately 600 men with primitive arms and few resources.[2] The regiment was made up of Colborne men with the surrounding townships supplying many of the men. Dunlop drilled his men in Read's Tavern while scavenging for blankets, coats, boot and more.[8] Dunlop commandeered supplies and food from Canada Company stores for the benefit of his men, leading to demands from the Canada Company for his withdrawal from militia activities. Dunlop refused, but resigned from the company later in 1838.[1]

Colonel Dunlop had five company commanders: Henry Hyndman, Thomas W. Luard, W.F.Gooding, Daniel Home Lizars, and Captain Annand. Late in December the government dispatches orders to the 1st Hurons and on December 25 Dunlop dispatches as follows:

- Hyndman's Company to Walpole Island on the St. Clair frontier

- W.F. Gooding near Sarnia

- Luard at Navy Island

- Lizars at Clinton

- Captain Annand as home guard at Goderich.[8]

Unprepared and poorly managed as the rebels were, the Rebellion of 1837 Upper Canada was quickly over. The Regiment of the Bloody Useless saw no action. Dunlop worked fiercely to ensure that his men were paid for their three months of service.

Political career: Member of Parliament

Summarize

Perspective

First term: 1841–1844

Hard-fought election

Dunlop left the Canada Company in 1838. When Dunlop resigned from the Canada Company the divisions in Huron County became more evident where the Canada Company provided some with a living and others with obstacles to overcome. Dunlop became the natural leader of an anti-Company group known as the Colbornites, residents in Colborne township.[1]

In February 1841, Dunlop's brother Robert died. Robert Dunlop had represented Huron in the assembly since 1835. The union of Upper and Lower Canada took place shortly after Robert's death. In the subsequent election later that year William ran against James McGill Strachan, the preferred candidate of the Canada Company. Strachan was the son of Bishop John Strachan, a leader of the Family Compact, and brother-in-law of Thomas Mercer Jones. Strachan lived and worked in York, while Dunlop was a local resident. Although Strachan had been thought to have little chance of winning, with one newspaper asserting that he had "...no more chance, than a stump-tailed ox in fly time," he was declared elected, by a majority of 10 votes (159 to 149).[9][10] He took the seat and participated in the initial proceedings of the First Parliament.[11]

Dunlop lodged a controverted election petition with the Legislative Assembly. Colonel John Prince, the member for the neighbouring riding of Essex, acted for Dunlop in moving the matter through the Assembly.[9] Two months into the session, during which Strachan participated as a member, the Assembly allowed Dunlop's appeal, ruling that unqualified voters had been allowed to vote in favour of Strachan. Dunlop was awarded the seat on 20 August 1841, replacing Strachan.[12][13][14] Dunlop sat as member for Huron for the duration of the first Parliament.

Legislative role

Despite his flamboyant character and occasional radical stances, in the legislature Dunlop took a moderate Tory position. He became notable for his humour. On one occasion, when the Assembly was debating whether to impose new taxes. Dunlop was speaking in favour and was interrupted by another member, who asked: "Would the honourable member advocate placing a tax on bachelors, as such?" The unmarried Dunlop immediately replied: "Certainly. I believe all luxuries should be taxed."[2]

In 1841 he chaired a committee to hear the grievances of the exiled radical Robert Fleming Gourlay. Dunlop's report was an even-handed treatment of Gourlay's situation[1]

Tiger was a colourful character and made interesting speeches and wrote direct letters to the newspapers of Toronto. Dunlop's short foray into journalism gave him the knowledge of the trade to catch the eyes of the editors in London, England.

Voting record

Dunlop's record as a parliamentarian demonstrates that he did not vote along party lines. This is not an exhaustive list, but a list that is meant to provide some insight into the thought and ideology of a man of contradictions who genuinely spans the Tory to Reform spectrum in the early days of Canada.

- Education – always voted to improve schooling for the general public.[15]

- Secular university to replace the Anglican King's College; later known as the University of Toronto. Voted yes.[16]

- Choice of Speaker of the House 1844 – Voted for a bilingual member to take the position.[17]

- Should magistrates be lawyers? – Voted no.[18]

- The lawful use of corpses to facilitate the study of anatomy – Voted yes.[19]

- Customs union with the British West Indies – Voted yes.[16]

- Forbidding of processions by private societies; aimed at the Orange Lodge. – Voted yes.[16]

1st Warden of the District of Huron

As a member of Parliament, Dunlop was appointed as the 1st Warden of the District of Huron. With his experience as the Canada Company Warden of the Woods,[20] Dunlop was uniquely qualified for this work. However, his methods often left questions in the minds of those around him and he was replaced in 1846.[1]

Second term and resignation

In the general election of 1844 Dunlop ran unopposed.[14]

Dunlop resigned his seat in 1846. It is not clear why he did so. However, two reasons are generally cited for the resignation; health and alcohol. The years spent living in the primitive forests of Canada and the ever-increasing use of alcohol appear to have taken a toll. William Tiger Dunlop was a tired and sick man.[8] Tiger was not taken seriously in Parliament or in the newspaper editorials of the day. Unfortunately, the two political concepts of the Parliament of Canada that he could not absorb were responsible government and the concept of group or social liberty. Dunlop firmly believed in individual liberty and in patronage. Moreover, Dunlop was far ahead of his time on other issues, such as education, professional independence, commerce and the rights of French Canadians.[8] Dunlop was tired of the fight and the irrelevant place he had carved for himself in Parliament with his outspokenness.

Tory ministers William Henry Draper and Denis-Benjamin Viger apparently wanted their colleague Inspector General William Cayley to have a safe seat in parliament and looked to Huron. Dunlop was offered the superintendency of the Lachine Canal in return for his seat. To the surprise of all, Dunlop accepted the post.[1]

Character

Summarize

Perspective

Origins of the nickname "Tiger"

Dunlop was known under a variety of nicknames, but the one that has lasted and remains with him to this day is "Tiger". In Upper Canada, he was also known as The Doctor, Peter Poundtext, or Ursa Major and often as The Backwoodsman.[1]

- The Doctor, of course, is a reference to his professional occupation

- Poundtext is a word play on a type of loan, where no matter the credit rating of the borrower, he may borrow and then repay in seven days.

- Ursa Major is a constellation containing the Big Dipper—another financial reference to Dunlop, but probably more accurate is Ursa Major containing the great bear, a reference to Dunlop's herculean body.

- The Backwoodsman refers to his life as a frontierman.

The nickname "Tiger" is supposed to have been given to him during his time in India.[1] Some sources describe it as Dunlop participating in a sport; others describe it as a business trip. The combination of two seems to be more inline with Dunlop's character. The business trip included a cull of the Saugor Island tigers.<ref=DCB/>

Stories of the legend

During his time and certainly after William Tiger Dunlop became a legend. It was common for people to seek him out just for the pleasure of having been said to have met Tiger Dunlop. The stories that surrounded him became the stuff of legend; some verifiable, some not.

Impersonating a general

Dunlop and a fellow army friend had been ordered to join their regiment on the Niagara frontier two hundred and eighty miles from their present location in Kingston. Although the road from Kingston to Niagara had many post houses, they were not well supplied and junior officers came in low in the pecking order. It became common for Dunlop and friend to find worn out nags available as their transportation. Being in a hurry, the two men decided to speed up the process and gave themselves instant promotions. Dunlop became a major-general and the friend became his aide. The "aide" demanded good horses for his general who had apparently been sent by the Duke of Wellington to instruct Sir Gordon Drummond on how to conduct the campaign. With no shortage of the theatrical in their nature, the imposters pulled off the hoax and rode good horses. Dunlop was twenty-two at the time.[8]

Regiment of the Bloody Useless

During the Rebellions of 1837, William Dunlop, who had become a Colonel, was requested to raise a militia unit that would become known as the 1st Regiment Huron Militia. The Regiment consisted of some 600 badly outfitted and ill-equipped men. The Regiment experienced great difficulty obtaining even the most rudimentary supplies according to the Memorial by Lieutenant-Colonel Taylor 1st Regiment Huron Militia to the House of Assembly of the Province of Upper Canada in Provincial Parliament Assembled. Dunlop nicknamed the militia unit "The Bloody Useless."[2] Little wonder that the 1st Regiment Huron Militia played no significant role in any of the activities of the Rebellions. Notwithstanding that Dunlop was still an employee of the Canada Company while engaged in this Militia activity, Dunlop took it upon himself to commandeer supplies and food from the Canada Company so that his soldiers could eat and defend themselves.[1]

Marriage

William and his brother Robert Graham Dunlop shared a home near Goderich, at Gairbraid (now known as Saltford, Ontario). Being both bachelors and unaccustomed to domestic work, they sent home to Scotland for a housekeeper. Louisa McColl arrived in Canada to take care of the two brothers. Shortly after, tongues began wagging and it soon became clear that Louisa's situation was insupportable and she would need to either marry or leave the country. Robert and William decided McColl was irreplaceable and tossed a coin to see which brother would marry Louisa. William supplied the coin and Robert lost the toss; after the wedding it became known that William had supplied a coin with the same face on both sides. Robert never objected.[1][2][21]

Crossing the US border

Dunlop was fond of snuff, a tobacco product. Like any other consumable, Dunlop enjoyed snuff in large quantities. The box in which he carried his snuff, he called The Coffin. Crossing the Canada/US border, a US inspector found it doubtful that the amount of snuff carried with him was just for personal use. Dunlop is said to have tossed a handful of snuff in the air, then snorting it as it fell around him. He said: "There, that's what I want it for; that's the way I use it".[1]

Nails in a barrel

Enjoying a good practical joke, Dunlop and a friend were passing the time in a Goderich store. A porcupine had been deposited in a barrel normally used for nails. As each person came into the store Dunlop would request help in getting a few nails. Dunlop's delight in shocking was spontaneous.[1]

Final years and burial

Summarize

Perspective

Tiger Dunlop died within two years of leaving the legislature on 29 June 1848, at the age of 56. He died in Montreal, while carrying out his duties as supervisor of the Lachine canal. Louisa, widow of his brother Robert, carried out his last wish to be buried in Goderich. It took two stages to move his body from Montreal to Goderich. Because of the summer heat, he was buried temporarily in Hamilton, en route to Goderich. The second stage was completed in January, when his body was moved to the family burial site at Gairbraid in Goderich, Upper Canada, where he was buried next to his brother Robert.[2][22]

Dunlop wrote his own will, assigning different mementos to his various family members, with humorous comments on their characters and personal idiosyncrasies. When he asked a friend to review it, the friend cautioned that it might be invalid because it treated such a serious subject with levity. Dunlop consulted his friend, Colonel Prince, a lawyer, who wrote back: "I have perused the above Will. It is eccentric, but it is not in that sense illegal or informal. To a mind who knows the mind of the testator it will remain a relict of his perfect indifference (an indifference to be commended, in my opinion), to what is called Fashion, even in testamentary matters."[2]

Memorials

The Tiger Dunlop Plaque can be found near his gravesite in Goderich. The text particularly commemorates his role with the Canada Company in populating the Huron Tract and in founding Goderich.

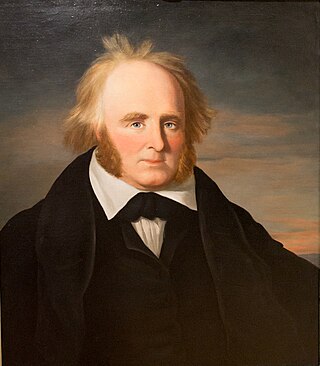

Dunlop's extremely varied life is summarised by the caption for the oils portrait of Dunlop donated to the Canadian Medical Association in 1931:

William Dunlop Esq., M.R.C.S.

1792 — 1848

"The Tiger"

Assistant Surgeon 89th Regiment

Lower Canada, Niagara, 1813–14; India, 1815–20

Lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence, Univ. of Edinburgh

Warden of the Forests, Canada Company

Lieut.-Colonel 1st Huron Regiment, 1837

Commissioner of the Peace, London District, 1838

M.P.P. for Huron, Parliament of Canada, 1841–45

Litterateur, Colonizer, Patriot.[2]

1792 — 1848

"The Tiger"

Assistant Surgeon 89th Regiment

Lower Canada, Niagara, 1813–14; India, 1815–20

Lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence, Univ. of Edinburgh

Warden of the Forests, Canada Company

Lieut.-Colonel 1st Huron Regiment, 1837

Commissioner of the Peace, London District, 1838

M.P.P. for Huron, Parliament of Canada, 1841–45

Litterateur, Colonizer, Patriot.[2]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

Dunlop's writing are best known for their depiction of Canadian frontier life in the Huron Tract. Dunlop wrote the following works under both the Backwoodsman and William Dunlop:[23]

- Recollections of the American war, 1812-14 by Dr. Dunlop ; with a biographical sketch of the author, by A.H.U. Colquhoun (Toronto : Historical Publishing Co., 1908).

- Statistical sketches of Upper Canada : for the use of emigrants, by a backwoodsman (London: J. Murray, 1832).

- Two and twenty years ago : a tale of the Canadian Rebellion, by a backwoodsman (Toronto : Cleland's Book and Job Printing House, 1859).

- Statistical sketches of Upper Canada : for the use of emigrants, by a backwoodsman, 3rd ed. (London: J. Murray, 1833).

- The Vagary, or, The last labors of a great mind, compiled from original documents ; with an appendix ... ; adapted to the times by a backwoodsman (Conneautville, Pa.: A.J. Mason, 1856).

- Lands in the Huron district (Toronto : Rowsells & Thompson, 1843).

- An address delivered to the York Mechanics' Institution, March, 1832, by Dr. Dunlop. Printed for the Mechanics' Institution at the Guardian Office (York: W.J. Coates, 1832).

- To the freeholders of the county of Huron : my friends and neighbours, it was only yesterday that I saw by accident, in an obscure print, the name of which I never before heard, an attack upon me by Mr. Morgan Hamilton (Upper Canada, 1841)

- Upper Canada, by a backwoodsman (London: John Murray, 1832).

In addition to these known works, there has been some discussion whether Dunlop was involved in some way in the creation of the Canadian Boat Song.[24]

Bibliography

- Byfield, Shadrach, Two British Soldiers in the War of 1812 : the accounts of Shadrach Byfield and William Dunlop, edited and annotated by Stuart Sutherland (Toronto: Iser Publications, 2002).

- Coleman, Thelma and Anderson, James, The Canada Company (Stratford, Ont.: Cumming Publishers, c1978).

- Dunlop, William, Tiger Dunlop's Upper Canada : comprising Recollections of the American War 1812-1814, and Statistical sketches of Upper Canada for the use of emigrants by a backwoodsman, introduction by Carl F. Klinck (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, c1967).

- Ford, Frederick Samuel Lampson, William Dunlop (Toronto: Murray, 1931).

- Ford, Frederick Samuel Lampson, William Dunlop 2nd ed. (Toronto: Britnel, 1934).

- Graham, William Hugh, The Tiger of Canada West (Toronto : Clarke, Irwin, 1962).

- Klinck, Carl Frederick, William "Tiger" Dunlop, "Blackwoodian backwoodsman" (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1958).

- Stewart, I. Anette. "The 1841 election of Dr. William Dunlop as member of parliament for Huron County", Ontario History (1947), vol. 39.

- Tazewell, Samuel Oliver, Portrait of William Dunlop. (Published for the Canadian Literary Magazine, York 1833).

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.