Wheeler & Wilson

Former American sewing machine company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Wheeler & Wilson was an American company which produced sewing machines. The company was started as a partnership between Allen B. Wilson and Nathaniel Wheeler after Wheeler agreed to help Wilson mass-produce a sewing machine he designed.[1] The two launched their enterprise in the early 1850s, and quickly gained widespread acclamation for their machines' designs.[1] Both Wheeler and Wilson died in the late 19th century, resulting in the company's sale to the Singer Corporation.[1] Shortly after, the Singer Corporation phased out Wheeler & Wilson's designs.[1] The company sold a total of nearly 2,000,000 sewing machines during its existence.[1]

| Industry | Sewing Machines |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Warren, Wheeler & Woodruff |

| Founded | 1853 |

| Defunct | 1905 |

| Fate | Acquired by Singer Corporation |

| Headquarters | 1853–1856: Watertown, Connecticut 1856–1905: Bridgeport, Connecticut , United States |

Company history

Summarize

Perspective

Formation

Throughout the late 1840s, Allen B. Wilson traveled throughout the United States as a journeyman, and conceived the idea for a sewing machine in 1847, unaware that it had already been invented.[2][3] By 1848, Wilson moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and began creating drawings for a sewing machine, before eventually beginning construction one on February 8, 1849.[2][3] By April 1, 1849, Wilson completed his prototype, which he sold for $200.[3] Using this money, Wilson acquired a patent for his sewing machine on November 12, 1850, which differed from existing models in that with each movement it inserted two stitches instead of one.[2][3]

Nathaniel Wheeler, who had previously met Wilson while on a business trip in 1849, met with Wilson again in August 1851.[1] Wheeler contracted Wilson to produce 500 sewing machines for Wheeler's existing business in Watertown, Connecticut: Warren, Wheeler & Woodruff.[1][4] During this time, Wilson filed a patent for his machines' rotating hook and its four-motion feed.[2] In October 1853, Wheeler and Wilson used $160,000 to officially relaunch their enterprise as the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Co.[1][4] Wheeler incorporated the company with Alanson Warren, who served as its first president, and George P. Woodruff, who served as the company's first secretary and treasurer.[5] The other general offices of the company were held for many years by Isaac Holden as vice-president, William H. Perry as general superintendent, secretary and treasurer, and Frederick Hurd as secretary and treasurer.[5] Wheeler served as the company's General Manager, and became the company's President in 1855 following Warren's resignation.[4][5]

Initial expansion

The company began producing these sewing machines in Watertown, producing 3,000 units before relocating to Bridgeport to take advantage of the city's superior transportation links, communication links, and a larger facility size.[1][3][4][6] Here, the firm occupied a facility which formerly belonged to the Jerome Clock Company.[4]

Later years

By 1859, the company had the most sewing machine sales in the United States.[2] The company's capital stock was increased in July, 1859, to $400,000, and June 29, 1864, the company was granted a special charter by the Connecticut state government, and the capital stock was further increased to $1.000,000.[5] During this time, the company's sales grew exponentially, from just over 21,000 units in 1859, to nearly 130,000 twelve years later.[2] Allen Wilson died in Woodmont, Connecticut on April 29, 1888.[1][3] Nathaniel Wheeler continued to serve as the company's General Manager and President until his death.[5] Wheeler died in Bridgeport on December 31, 1893.[1][4] After Nathaniel Wheeler's death, his son, Samuel Wheeler, succeeded to the presidency. His official associates were George M. Eames, vice-president, and Newton H. Hoyt. secretary and treasurer.[5]

Acquisition by the Singer Corporation

By 1905, Wheeler & Wilson were employing about 2,000 hands at their facility in Bridgeport.[5] Singer Corporation took over the Wheeler and Wilson Manufacturing Company in 1905.[1][6] After the acquisition, Singer continued to promote Wheeler and Wilson machines for a number of years,[1] and continued producing their No. 9 model sewing machine under its own brand name until at least 1913.[6]

Sales by year

The following table shows the company's unit sales by year:[2]

| Year | 1853 | 1859 | 1867 | 1871 | 1873 | 1876 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales | 799 | 21,306 | 38,055 | 128,526 | 119,190 | 108,997 |

Awards

Summarize

Perspective

The company won a number of Prize Medals, including at the 1861 Industrial Exposition in Paris,[1][6] the 1862 International Exhibition of London,[1][6] the Exposition Universelle, Paris 1868, the 1878 Exposition Universelle,[6] and 1889 Exposition Universelle.[6]

At the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, Wheeler & Wilson was the only sewing machine company to be awarded the Grand Medals of Progress and of Merit.[7]

According to advertisements run by the company, other awards they received include the Gold Medal of Honour of the American Institute of New York, in September 1873, the Gold Medal at Maryland Institute in October, and a Silver Medal (the highest premium for "Stitching Leather") at the Georgia State Fair in November 1873.[8][9]

In July 1874, the jury awarded the First Prize, a silver cup, on account of the "ease of working, the little noise, speed of executing work, and durability of the sewing machines made by the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company.", at the Bury Agricultural Show in August 1874 the first prize, at the Manchester and Liverpool Agricultural Show on September 10, 1874 the Society's Silver Medal for "excellence of manufacture, progress and novelty in mechanism, and superiority of work done by it." and at the Cheshire Agricultural Society's Show in Warrington on September 23, 1874 the first prize.[citation needed]

Sewing machine innovations

Summarize

Perspective

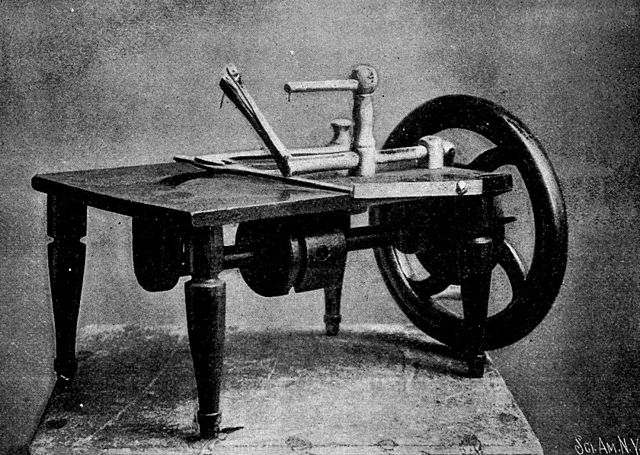

Allen B. Wilson filed two important patents for Wheeler & Wilson's sewing machines: the rotating hook and the four-motion feed.[2] His first machine formed a lock stitch by means of a curved needle on a vibrating arm above the cloth plate, and a reciprocating two-pointed shuttle traveling in a curved race below the plate. The feed motion was obtained by the two metal bars which are seen intersecting above the shuttle race. The lower bar, called the feed bar, had teeth on its upper face, and by means of a transverse sliding motion it moved the cloth, which was placed between the two bars, the desired distance, as each stitch was made.[2]

Rotating hook

In 1851 Wilson patented the rotating hook, which performed the functions of a shuttle by seizing the upper thread and throwing its loop over a circular bobbin containing the under thread.[2] This simplified the construction of the machine by getting rid of the reciprocation motion of the ordinary shuttle, and contributed to make a light tool silent running machine, eminently adapted to domestic use.[2]

Four-motion feed

In 1852 Wilson patented his four-motion feed, which, as its name indicates, had four distinct motions: two vertical and two horizontal.[2] The machines' feed bar is first raised, then carried forward, then dropped, and finally gets drawn back by a spring to its original position.[2] This machine used the curved needle and embodies the rotating hook and the four-motion feed.[2]

- A copy of a Wheeler and Wilson number 4 machine made under licence by Gibson Brothers at Hebden Bridge C1866

- A number 8 machine.

- A number 9 machine.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.