Remove ads

Waterways in West Virginia find their highest sources in the highland watersheds of the Allegheny Mountains. These watersheds supply drainage to the creeks often passing through deep and narrow hollows. From the hollows, rushing highland streams collect in bottom land brooks and rivers. People have lived along and boated on the waterways of what is now the Mountain State from the time of antiquity.

Remove ads

On July 13, 1709, Louis Michel, George Ritter, and Baron Christoph de Graffenried petitioned the King of England for a land grant in the Harpers Ferry and Shepherdstown area in what is now Jefferson County, in order to establish a Swiss colony. Neither the land grant nor the Swiss colony ever materialized. However, the early British fur trade outpost, Fort Conolloways (today Tonolloways) with the "Canallaway", "Cawnoyes" and "Conestogoes" tribes appeared near the mouth of the Conococheague on the Potomac River after 1695.[2] The Treaty of Albany (1720) designated the Blue Ridge Mountains as the western boundary of white settlement.[3] Orange County, Virginia, was formed in 1734. It included all areas west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, constituting all of present West Virginia. By 1739, Thomas Shepherd had constructed a flour mill powered by water from the Town Run or the Falling Springs Branch of the Potomac River. Shepherd, along with Isaac Garrison and John Welton, established the present town of Shepherdstown in today's Jefferson County. In October 1748 the Virginia General Assembly passed an act establishing a ferry across the Potomac River from the landing of Evan Watkin near the mouth of Conococheague Creek in present-day Berkeley County to the property of Edmund Wade in Maryland. Robert Harper obtained a permit to operate a ferry across the Shenandoah River at present-day Harpers Ferry, Jefferson County in March 1761.[3] Thus, these two ferry crossings became the earliest locations of government-authorized civilian commercial crafts on what would become West Virginia waterways.

Remove ads

For nearly 15 years, missionaries and "coureurs de bois" confused ideas of a "beautiful River, large, wide, deep, and worthy of comparison . . . with our great river St. Lawrence" that in 1660 and 1662 they were able to describe a river below the Great Lakes to France. In 1670, Jesuit Dablon was able to write a good description of this river. Sulpician missionaries Dollier de Casson and Bréhant de Galinée, using their contacts with the natives, reported in 1671 the aboriginal names of the Ohio or Mississippi ("Ohio", in the Iroquois language, and "Mississippi", in the Ottawa language, both mean "beautiful river"—belle rivière).[4] The French Canadian Sulpicians had replaced the Jesuit Fathers, who had replaced the original Récollets. Confused European cartographers' ideas about the Ohio Country continued somewhat beyond the first decade of the 18th century.

In 1691–92 the British sent an envoy to the Shawnoe, who were called the "further Indians" (Broshar, 1920:232) by some at this time. Dutchman Arnoult Vielle commanded this float down the Ohio River to as far as the "Falls of Ohio". Captain Arent Schuyler returned to New York from the Minisink Indians of New Jersey in February, 1694. He was told by them that, "six days agoe three Christians and two Shanwans Indians who went about fifteen months agoe with Arnout Vielle into the Shanwans Country were passed by the Minnissinek going for Albany to fech powder for Arnout and his Company."[5] On September 11, 1694, Henri de Tonti made his report to France saying, "We have even been advised that one named Annas (Arias?), of the English nation, accompanied by the Loup[6] savages has had some speech with the Miami in order to draw them to them, which will give them a strong foothold for the success of their enterprise, if he corrupts them."[7] With the help of a large number of Shawnee, and some from seven other "nations", portering beaver furs with Arnoult Vielle, they arrived in Albany, New York, at the end of a very lucrative two-year hunt in the Ohio River Valley. "A band of Shawnee left their hunting grounds on the Cumberland (River, Ky) to follow Viele east to the Delaware River where they established a settlement."[8] In August 1699, Iberville reported to France saying, "some men, twelve in number, and some Maheingans who are savages whom we call Loups started seven years ago from New York in order to go up the river Andaste which is in the province of Pennsylvania, as far as the River Ohio which is said to join the Wabash, flowing together into the Mississippi."[9] Perhaps not the first white man to go boating on the Ohio River, but, Arnoult Vielle was the first well documented as such.

Buffalo skin canoes

There have been hints in the old tellings within circles about skin-covered canoes in the Kanawha region.[10] In mixed company, these were met with scoff. Trapper James (Jacob) Le Tort Sr. moved his Penn permit (1720s~30s) trading house near Letart Falls (namesake at the Jackson and Mason county line) from the Allegheny's Beaver Creek area fur trade by 1740, where his son married a Shawnee maiden. Along with them, much of his trade was coming from Little Kanawha River tributaries and Mill Creek, which reaches into Roane County to the Elk River watershed. Western Virginia "Cherokee" were reported at Cherokee Falls[11] (today's Valley Falls) in 1705 and continued the many Kanawhan old fields. Soon, these evolved into a fireside cabin culture with the pioneer, too.[12] They had not been quite like Keetoowah, seldom called to counsel by the Ahniyvwiya. Some migrated north of Daniel Boone's Kentucky settlement before he arrived, but not all for the assimilation with local Virginia colonizers. There were several different historical tribes in the Kanawhan region during the 18th century, including the Bulltown Delaware. A Mingo Indian statue commemorates the first inhabitants of the tributaries of the Monongahela, Potomac, Greenbrier, Elk, Tygart, and Gauley highland watershed's divide, near the village of Mingo Flats.[13] Simply, none were villaging at that particular year on any Old Fields on the Kanawha River during Salling's expedition, nor did he report any people on the lower Ohio, only describing the "Ohio Falls" area as a "Spanish Manor".

There is a gap between the Mill Creek lowlands and the large Great Kanawha bottoms that was an eastern black buffalo (Eastern Forest Buffalo) migration route.[14] Wonderful West Virginia magazine, in July 1976, Pp. 27 & 28, "W.Va. Wildlife 1776", by Maurice Brooks mentions these extinct buffalo achieved two hundred years ago along the Pennsylvania border (omitting person's name). Similarly, "The last buffalo seen here was killed on Little Coal river, in what is now Boone county, about half a century ago (~1826), and the last elk was killed (omitting person's name), on the waters of Indian creek of Elk river, about the same time."[15]

Salling did not bother to visit Le Tort and his clientele on the east branches of the Kanawha River. Salling explored and named the Coal River as we call it today which was Huntington's Guyandot namesake Guyandotte River and southern Ohio's Shawnee farthest reach of hunting land at that time. These folk's period peaked with the Treaty of Fort Meigs. Exposing the buffalo skin boat present in West Virginia is braved in this section with the use of the following quote:

(sic) "In 1742, John Peter Salling and four or five others crossed the entire state of West Virginia without seeing a human being who made the region his home. They descended the New River from near the point where Batts saw it, and passed down the Kanawha to the Ohio, traveling in a boat made of buffalo skins." See Christopher Gist's Journals, and accompanying papers, published by William M. Dunnington, Pittsburgh, pages 253 and 254.[16][17]

Birch bark canoes

Before the ever-increasing demands of the European fur market, the rivers carried more mundane Native American goods. Corn and a "Kentucky Wonder" like string beans within the broad scope of adjoining regions' natural resources included oceanic marine shells. Various were the ancient waterway's freight.

Frontier freight included highland spice, such as Highland "ginger", creek-bank "spearmint" (mint julep), "peppermint" (Mentha canadensis) still used today, ginseng, hollar slippery elm aspirin-like and yellow birch medicinals. Other freight consisted of various dyes and minerals such as Kanawha red salt, Elizabeth surface crude oil or the "snake oil" springs and New River sulphurs and saltpeter, which were illegal to process for black powder in the colony by English guild demands. At the time, black powder was often hard to re-supply locally to the Native gatherers and pioneer Trappers.[19] Goods were canoed down major streams in the state to the few trading posts. After the local trade was made, horse-trains continued the pack across the gaps eastward and off-loaded onto boats to continue the trek down larger rivers to waiting ships at the bay.[20]

The mountain streams of the eastern side of the state from Pendleton, Grant, Hampshire and Hardy counties include the Cacapon River, Patterson Creek, Sleepy Creek, Back Creek, Opequon Creek and the South Branch Potomac River. "As early as 1721 a trader had built a cabin at the confluence of the Conococheague Creek and the Potomac River at what is now Williamsport, Md., about a dozen miles north of Martinsburg, W.Va. He was on friendly terms with the Indians (particularly the "Canawest Treaty") and so the most important inroad to the wilderness was opened, the Potomac River ("Co-hon-go-ru-ta")."[21] Charles Poke's trading post dates from 1731 at Cherokee Falls and sending upland forest goods and trade ware across this inroad. This ancient east-west mountain trail, crossing the Seneca Trail, generally follows today's U.S. Route 50 to the Potomac River. Local trails and waterways in northern West Virginia tributaries of the Monongahela River connected with Nemacolin's Trail, beginning at Redstone Old Fort as it was called in the 18th century.[22]

French Quebec canal engineer Chaussegros de Léry boated down the Allegheny and Ohio rivers in 1729. He was a noted fortifications engineer. A group of canoes under the direction of Charles Le Moyne reconnoitered down the Ohio River in 1739. The curiously found "elephant-like bones" (mastodon) became the talk of the colonies. The official colonial surveyors traveled the river in large styled birchbark canoes. It has been reported by many historians that much more than a dozen men would paddle these. The frontier clinic doctors often came along to make their "treaty" stops at fur collection villages. The reports and letters were transported by these boaters to Fort Henry (present-day Wheeling, West Virginia), and Fort Pitt (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). According to the "Draper Papers" and a few earlier historians, Simon Kenton had his first trading house at the mouth of the Elk River at today's state capital city on the Kanawha from 1771 and went by the name of Butler. There are local tales of canoeing up to his landing to trade about the year colonial surveyors such as Mr. Taylor, Captain Crawford and George Washington proceeded on the first surveys here from 1770. Native American canoe porters were seldom mentioned in these journals. A considerable amount of goods were being moved to the east and Canada during the earlier decades on the region's waterways.

Another colonial surveyor, gone boating on the Kanawha and Ohio rivers, was Captain Hanson in April 1774. While on the Kanawha River and quoting from his journal: "16th. We proceeded to Elk River, 6 miles (9.7 km) & found the canoe on the opposite shore of New River. Mr Floyd and a stranger went out to hunt; whilst we finished the canoe, which was done when he returned, after shooting a Deer & a Pike 43 inches (1,100 mm) long." "17th. We called our canoe the Good-Hope, imbarked on board of her, sailed 9 miles (14 km) down the river, there saw two canoes ashore, which caused us to land, We found Majr Fields in company...The People informed us, that the Indians had placed themselves on both sides of the Ohio, and that they intended war. The Delaware Indians told them that the Shawnese intended to rob the Pensylvainans & kill the Virginians where ever they could meet with them, We parted with them & proceeded to Crab River 3 miles (4.8 km)." "18th. We surveyed 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of Land for Col. Washington, bordered by Coal River & the Canawagh..." "19th. We passed on from hence, passing Pokatalico River at 6 miles (9.7 km), to a bottom Mr. Hogg is improving in all 14 miles (23 km), Mr. Hogg confirmed the news we had of the Indians, He says there were 13 People who intended to settle on the Ohio, and the Indians came upon them and a battle ensued..." "20th. We proceeded to the mouth of the Kanawha, 26 miles (42 km). At our arrival we found 26 People there on different designs – Some to cultivate land, others to attend the surveyors, They confirm the same story of the Indians. One of them could speak Indian language, therefore Mr. Floyd & the other Surveyors offered him 3 per month to go with them, which he refused, and told us to take care of our scalps..."[23]

Before the dams began to be built in 1885, Wheeling was known as the "head of dry navigation" during drought. The path between the two locations was used for dispatch, at the time an overnight trip. The officials accompanied by a few friendly scouts of employ could otherwise canoe them and material more quickly[24] to Fort Henry and down river to as far as Fort Kaskaskia, a small garrison trading post associated with Colonel George Croghan et al. The block house (small forts) construction material were more often moved on rafts called flatboats.

Chief Cornstalk's Shawnese (Chalahgawtha) word for canoe was "Olagashe". Again locally, the Ohio River was also called "Spaylaywitheepi" in Shawnese at the Lower Shawnee Town.[25] Shawano, Hulagî'si punhanwi, the boat is landing.[26] Iroquois (Tuscarora, Mingoe & Canawagh) call the Kanawha River "Kahnawáʼkye" meaning "waterway" (transport-way), and "kye" is an augmentive suffix. In this context, it renders "Much Transport Way", or "Big Waterway". "Kaháwa'" is a noun phrase meaning "boat" (canoe). It varies with "kahôwö'". "Uhíyu'" is a verbal nominal meaning the Ohio River or the state of Ohio. It belongs to the semantic field places. Etymology [u]- NsP/I prefix, -(i)h- /river/, -íyu- /be good, beautiful/, -' Noun suffix. Literal translation is "the beautiful river". The phrase "Kentucky" is also from "Ken-ta-ke", a Mohawk (Iroquois or Six Nations) word signifying "among the meadows". (List of names of places given to Dr. Hough, by an intelligent Indian of the Cahnawagas, or French Mohawks, of the tribe near Montreal. Hough's "History of St. Lawrence County," New York. 1858.)

Flat boats

George Washington and Christopher Gist's raft was destroyed by floating ice, stranding them on the Allegheny River's Garrison Island on December 29, 1753. A frigid night allowed them to walk from the island the next morning. Washington also wrote of the coal outcrop burning on the ridge above West Columbia in Mason County, as university scholars identify.[27] The civilian Ohio River flatboat era began about the time Colonel Brodhead had command at Fort Pitt, 1778–81. His reports and letters became public in the early 1850s.[28] With the assistance of friendly Kanawha and Monongahela Indians his army retaliated hostiles coming down the Allegheny River. His campaigns continued which defeated the war chiefs from Ohio in 1781 who came to power after "White Eyes" died. This clearing of hostiles on the upper Ohio River system aided arrivals from Europe to build flatboats to take them to their new pioneer homes. Some French and Indian War veterans sold their patent surveyed land for cash to frontier settlement arrivals, not wishing to uproot from their already established easterly homesteads. Many settlers came down the Ohio from the Forks of Ohio and the young town of Wheeling, located at the end of the Cumberland Road, building their flatboats there. By 1800, a variation as a houseboat was called an arc. It included a "fireplace" (Franklin stove?) within the cabin. One of these is recorded being anchored within the Crooked Creek embayment near the Boone trading post at Kanawha Harbor.

Kanawha salt was moved downriver on flatboats in greater quantity than earlier occasional sacks aboard canoes. In 1782, Jacob Yoder launched from the Monongahela at Redstone with a cargo of produce, according to his friend Joseph Pierce of Cincinnati, another flatboat captain. This first commercial attempt reached New Orleans having drifted through the dangerous Spanish region. These crews walked back to their home on the Ohio River, passing through the deep South's Spanish lands. The shipping of coal on West Virginia rivers began about 1803. Fort Nelson (Louisville) and Fort Washington (Cincinnati, the population of which was about 950 at the time) were notable stops. The population of western Virginia was about 100,000 in 1810. The old river jetties did not stop the usefulness of flatboats. Variations of these were built through the following decades. They were used on the Ohio into the 20th century. They all were difficult to maneuver through the early dam's locks and by that time, steamboats' barges had replaced them.

Remove ads

The larger pirogue is more famous on the lower Mississippi River. The earlier ones were carved from cypress and sycamore. Some of these were nearly 50 feet (15 m) long and 5 feet (1.5 m) wide. These French pirogues often had a small sail which could relieve them of their pole and paddle propulsion. As their carpenters came onto the frontier, they made them with planks and a flat bottom. Spanish vessels on the Mississippi River system's shoal waters were similar.

On August 12, 1749, Celeron de Bienville, a French officer and his flotilla of canoes, "encountered two canoes, loaded with packs and guided by four Englishmen." On the August 13, he "encountered several pirogues, conducted by Iroquois, who were hunting on the rivers which intersect the land," the rivers of the western Kanawha region along the Ohio River. Of the Great Kanawha River he records: "The 18th, I departed at an early hour. I camped at noon, the rain preventing us continuing our route. I have this day placed a lead plate at the entrance of the river Chiniondaista and attached the arms of the king to a tree. This river carries canoes for forty leagues without encountering rapids, and has its source near Carolina. The English of this government come by treaty to the Belle Rivière."[29]

The West Virginia pioneers along the river built a square-sided canoe using boards butted together. The construction is similar to their building these waters' more common flat-bottomed rectangular rowboat used for fishing and river crossing of local goods. The smaller and lighter canoe shape was better suited for one person to cross over gentle rapids (portage) and paddle upstream on the Ohio River.

Pirogue mail carrier

The Northwest Ordinance was passed unanimously by the Congress of the Confederation of the United States on July 13, 1787. On August 7, 1789, the United States Congress affirmed the ordinance with slight modifications under the Constitution. In 1787, pirogues began use on the upper frontier river for carrying the mail. The new United States government paid these boaters to relay mail along the Ohio River in two-week intervals between Wheeling, Marietta, Maysville and Cincinnati, with short stops along the West Virginia and Ohio settlements. To be hired as a pirogue mail carrier, a candidate had to demonstrate above-average boating and swimming skills and was required to be frontier savvy. The mail pouch was strapped securely to his body in case of a boating accident. Fort Henry at Wheeling was the Mail Master's collection point for the Pirogue mail carriers.

Remove ads

Between the hostile "Old Frontier" Indians and river pirates, the outrage by eastern investors to the frontier reached a point that something had to be done. The resulting action was known as the Northwest Indian War or the "Old War". The order was given to build a new frontier army and boats for logistics support. Keelboats, ranging from 50 to 100 tons, can be considered to have started with the efforts of Major Craig of Fort Pitt. Craig wrote to General Knox on March 11, 1792, and again in a report dated May 11, 1792 about these better-built boats and their cost.[30]

The next year, 1793, with the upper West Virginia rivers firmly under Major Craig's control, saw the first regular packet line on the Ohio River. It was a weekly keelboat trip between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh with short stops at other West Virginia and Ohio river settlements. Cincinnati merchant Jacob Meyers saw the need in this year. His vessel was built similar to Lewis and Clark's adventure galley, another variation of a keelboat. Individual packets' round-trips had taken about a month during the hostile era and some did not survive. This inspired merchant Meyers to start his "Line".

Keelboat mail carriers

An advanced route was scheduled with a relay system in June 1794. Six rowers and maybe a passenger or two paddled between Maysville, Gallipolis, Marietta and Wheeling. The government mail carriers relayed between their two assigned towns on a one-week turn-around. Each team stayed at their landing towns until the next relay team arrived. After the exchange, they soon made departure to ensure the one-week delivery. A passenger was to carry his own pouch of food, and a weapon was highly encouraged for his own personal protection.

Remove ads

The keelboat builders Tarascan, Berthoud & Company of Pittsburgh built the 120 ton schooner, Amity and the 250 ton Pittsburgh in 1792. In 1793, these were loaded with flour; one was sent to St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands and the other to Philadelphia. Coal used as ballast was sold in Philadelphia at 371⁄2 cents a bushel the next year on two of their brigantines, 200 ton Nanina and 350 ton Louisianna. The largest was the 400 ton brigantine Western Trader. Before 1803, the 70 ton gaffed rigged schooner Dorcus & Sally was built at Wheeling and fitted at Marietta, Ohio. Also, the 130 ton Mary Avery was built at Marietta. The 100 ton schooner Nancy was launched on June 27, 1808, at Wheeling and among others to include Little Kanawha before the era of the paddlewheelers. The uncommonly long wild black walnut timber used for hull construction, written in a journal of a coastal purchaser's observer, were a little lighter yet as strong as the heavier oak hull timber used at that time on the east coast. Some shipwrights from Rhode Island arrived about this time to join their neighboring regionals who had already relocated along the river's old growth forest shipyards. A few of these walnut-hulled schooners were sold with their freight, and a few were fitted as North American gun cutters (escort/patrol) with others of the US privateers during the War of 1812. One was also noted in the Caribbean. In January, 1845, Liverpool, England, not believing the marque home port and having to be shown the geography thereby not pirates, welcomed the Marietta-built 350 ton barque Muskingum. This was a cheerful first for Ohio River crews. The largest built was the ship Minnesota at Cincinnati of 850 tons for a New Orleans owner. A steaming paddlewheeler delivered it.

A few locally built and crewed barques made passage to Africa and back to the Kanawha region before the Civil War. These larger vessels moved during spring flood waters, having a little more draft than our earlier more common schooner's berthy 11-foot (3.4 m) draft or less, which were more able. The early upper Ohio Valley vessels' cargo included flour, smoked beef, barreled salt pork, glass-wares, iron, black walnut furniture, wild cherry, yellow birch and various beverages. Much of the bulk cargo were stored in flat-bottomed square-end "jonboats", as crates above the hold for some destinations required a davit method of loading and unloading the freight. It was during this era that sorghum and the Kentucky variety of tobacco were exported in greater volume from farmers in western Virginia's large bottomlands boat landings.

Remove ads

Robert Fulton built the valley's first commercial paddle-wheel steamboat, New Orleans, at Pittsburgh and Captain Nicholas Roosevelt sailed it down the Ohio to New Orleans in 1811. But it was not able to navigate back upriver from Natcheys. It was side-wheel driven with a low-pressure boiler driver compared to following plants. The machine-powered river transportation industry was on its way with the steam-engine works at Pittsburgh of Oliver Evans and managed by Mark Stackhouse which began operations in May 1812. A plant from this shop went into the early local stern-wheel steamboat Comet, launched January 1813 (University of Pittsburgh's 'Historic Pittsburgh' ). Slowly replacing keel boats, the growing machine-powered vessel industry arrived in the state. In 1816, Captain Henry Shreve built the George Washington at Wheeling. It set the pattern for future steamboats. He named the passenger cabins, calling them staterooms, after U.S. states. This vessel was stern-wheel driven. Valley Forge is reported to be the first large iron steamboat on the upper Ohio Valley.[31] Robinson and Minis launched it at Pittsburgh in September 1839.

According to Dr. Hale's Early History of the Kanawha River Valley, "The first steamboat to attempt the navigation of the river (Great Kanawha) in the early days of steamboating on the western waters was the Robert Thompson in 1819. She went as far as Red House Shoals, but lacking power to stem the swift currents in that place abandoned the effort and returned." This was at the continued skeptical amusement of the local keelboat workers. Local tradition has team of horses was used to pull vessels over shoals. A team of large draft horse would later be on board some steamboats and jumped for hookup during the drought season. This unique 'horse handler', to use an old Army classification, was both blacksmith and boat mechanic, parallel the horse-drawn machine mechanic. This job position also worked along with the vessel's boiler engineer as coal tender (fuel loading), drive repair (paddlewheel system), and deck repair.[32] Henry Shreve designed the first steam-powered snagboat in 1829, The Heliopolis. Quoting the 'Tom Bevill Visitor Center', USACE Mobile District, "This double-hull design remained the standard until the early twentieth century with the development of high-strength steel hulls."

Hale continues, "In 1820 the Andrew Donnally, a steamer built by Messrs. Andrew Donnolly and Issac Noyes, salt makers of Charleston, made the first successful run to Charleston." Expanded later about the time Liverpool Salt Works at Hartford and other notable manufacture arrived along the logistic rivers, the salt industry barrel works was located at Crooked Creek at Kanawha Harbor. It provided containers for whisky used for lamp lighting and other considerations, West Columbia's nail works, and local farmer's salt pork and cheese barrels. The fruit and chicken crate-making firms were also scattered into the navigable tributaries. From the time of keelboat operators, river trade employee method progressed as new kinds of freight such as bricks and glass increased a few decades before the zenith of showboats and the railway matrix connected with Ohio River bridges after the Civil War.

During the American Civil War, Fort Union at the mouth of the Little Kanawha River at Parkersburg was the Union Army's supply center to the western states. With no railroad bridges crossing the Ohio River, this depot connected the eastern factories' rail to steamboat packets continuing the supplies west under this Quartermaster's command, the Upper Ohio Flotilla. This supply center was under the command of Quartermaster Charles Conley (Matheny 1989). Parkersburg was also the recruiting center for the 9th West Virginia Infantry (April 1862, Co K), who were often detailed on board to protect the packetboats and river crossings on the West Virginia rivers. Recruiter Col. Whaley and Lt. Col. William C. Starr, and Regimental Commander Gen. I. H. Duval were under Federal command at Wheeling, West Virginia. Many of these recruits came from a river worker's family tradition. "The regiment was composed largely of refugees, who, having been driven from home, were fighting with a desperation that was not excelled by any troops in any army." from the writings of Theodore Lang.[33] Livestock was commandeered to feed the assemblages on both sides (Matheny 1989). In 1862, Wheeling Command instructed the unit commanders to write receipts for local goods taken in the field. Also found in local older almanac-magazines, according to both Lang and Matheny, Richmond neglected this practice in the western region of the Old Commonwealth.

Recruited river workers and the flotilla of barges and civilian packets evacuated the salt miners, residents and civilian government during the "Confederate Overrun of Charleston, West Virginia". General William W. Loring pushed back Colonel Joseph A. J. Lightburn, but, the General knew when to stop and hold his ground. Ohio Generals had provided a significant artillery and brigade for this strategic recall trap. He did not chase after the flotilla to take control of the Mouth of the Kanawha thereby stopping Union river logistics to the Kentucky-Tennessee Theatre as some figured. The Confederate were after Kanawha Salt, nothing more. Horse-pack trains for weeks moved the salt for meat processing to the south. The Union command had earlier removed a significant number troops from the state for southerly battles. This had much weakened Lightburn's command, but, not his ability to protect the public. Much of the 9th were stationed at Point Pleasant to January, 1863 to guard the packets and refugees. The 5th Infantry Regiment and 106th Cavalry also patrolled until the retaking of Charleston a couple of months later. A few detachment of river troops remained well into the following year. Confederate brigadier general Albert G. Jenkins, son of a wealthy plantation in Cabell County, Virginia (W.Va.), from the area encampments of Roane County area his cavalry using the dragoon tactics (rush in, dismount and attack targets, remount rush away- also later of gongho air) attacked along the Ohio to as far as northern Kentucky. His primary targets were the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and supply packets at the Union procurement landings. These river crossings sentry and Colonel RBJP Smith's 106th militia of Jackson and Mason counties Cavalry continued their patrols watching for routine river crossing raids of the state's persistent Jenkins' Confederate Cavalry to reappear, until Morgan and his raiders showed up in Meigs County, Ohio.

Morgan's Raid was what brought the US Navy to the state's shores. Those river workers with Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's "amphibious division" were involved in the Battle of Buffington Island. These served on the Alleghany Belle. The Magnolia, Imperial, Alleghany Belle, and Union tin-clads and armed packets were documented privateers along with other smaller private owned salt ham and ammunition vessels under Parkersburg Logistics' command. Lt Commander Leroy Fitch's fleet included the Brilliant, Fairplay, Moose, Reindeer, St. Clair, Silver Lake, Springfield, Victory, Naumkeag, Queen City which were tinclads and ironclads under the U.S. Navy Mississippi Fleet Command. Ironclad USS Naumkeag patrolled from the Kanawha Harbor of the Mouth of Kanawha area. Springfield guarded from Pomeroy towards Letart Islands. Victory's cannon balls have been found along Leading Creek, Ohio, behind the period's boat yards. Its patrol was from Middleport, Ohio to Eight Mile Island with its sentry guarded crossing. Twice, Confederate scouting units found skirmish there. The last were cavalry scouts in retreat this time who saw armed vessels. The Ravenswood crossing saw the heat of the maneuvering skirmishes during the Battle of Buffington Island. The region's newspapers headline this routing as The Calico Raid for procuring personal goods from local stores and houses. Its position on the river and during the offensive phase before breakup, Pomeroy, Ohio was the last county seat in a solidly held Union state to be raided by this Confederate column. It was reported horsemen carried away scarce luxury gifts for the anticipative return home beyond encampment food stuff.

After the war, the steamboat Mountain Boy transported government officials and documents to Charleston from Wheeling after seven years there. The steamboats Emma Graham and Chesapeake moved the state's officials and documents back to Wheeling in 1875. After a citizens' vote in August 1887, the steamboats were again called on to move the state government and records back to Charleston. In May 1885, state government officials moved from Wheeling to Charleston on board the sternwheeler "Chesapeake." The ward barge "Nick Crewley" held the state records and library. It was pushed by the steam towboat "Belle Prince."[34]

Remove ads

The flood of January 9, 1762 destroyed much of Fort Pitt at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers. It had reached a stage of 39.2 feet (11.9 m) at the Point according to University of Pittsburgh's 'Historic Pittsburgh.' Major George Washington on November 23, 1753 described the elevation of normal pool, "The Land at the Point is 20 or 25 feet (7.6 m) above the common Surface of the Water". The next major recorded flood was on April 10, 1806 reaching 37.1 feet (11.3 m) above normal pool. It was followed by the 1810 flood of 35.2 feet (10.7 m) above normal pool. The flood of 1816 reached 36.2 feet (11.0 m). Not all floods developed in the Ohio Valley up-river the tributary rivers of the state.

The first recorded flood on the Ohio River along the West Virginia shores was in 1768. The Mingo survivors declared it was the highest known. It swept away their village near today's Steubenville, Ohio. The "Great Pumpkin Flood" occurred in 1811. After some days of drizzling rain, the storm increased causing a very rapid raise of the river. It washed away outhouses, out buildings and all sorts of ground drift. The bottom's pumpkin field's bumper crop was washed away.

The 1832 flood was exceptionally destructive compared to earlier floods due to increased individual capital investing. Government encouraged Homesteader's development had not figured on that occasion of extra high water levels on the flood plain bottoms. The 1852 flood was one foot lower than the 1832. Although, the steamboats were able to navigate over islands with no problem of grounding. With more industrial growth along the river routes, this flood was the first to wreck wealthy industry investors.

The Spring flood of 1860 was average 40 feet (12 m) above pool. Team of horse and plow method, many muddied bottoms did not make vegetables nor grain before first frost. The following year in 1861 during the fall saw a few more feet higher. Many of these fields did not mature soon enough. These series of floods and harsh winter devastated the farm bottom crops and two season's income. Furthering early Civil War hardship, gathering civil groups commandeered remaining farmer's seed stock during this period. Decades ago an elderly steampacket engineer out of Kanawha Harbor declared, the Rebels not only took the egg, but the chicken-two. The local small packet's egg run found little local produce to deliver to the river town markets. Support from the Union supply depot at Parkersburg Logistics Center reestablished in 1862 their local produce procurement. This assistance encouraged local farmers to side with the Union and some river workers to recruit (Matheny, H. E. 1987).

Remove ads

The US Congress has many records on waterways with a few here to example. "Monday, December 22, 1834, Mr. McComas presented a petition of inhabitants of the county of Kanawha, in the State of Virginia, praying that a law may be passed directing the judge of the United States district court for the western district of Virginia to hold annually two sessions at Charleston, in the county of Kanawha, instead of Lewisburg; which petition was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary."[35] "The Vice-President laid before the Senate resolutions of the legislature of Virginia, in favor of an appropriation to secure the early completion of the line of water communication between the valley of the Mississippi and the Atlantic Ocean, by connecting the waters of the James River and the Greenbrier River, and for improving the New, Greenbrier and Kanawha rivers which were referred to the Committee on Commerce."[36] Mr. Ellihu B. Washburne made a motion on January 13, 1859, to the Committee on Commerce to discharge considerations of the James River and Kanawha Company concerning Mr. Ellett's plan for supplying water in the Ohio River.[37] On March 31, 1870, Mr. Willey submitted a resolution to Congress: The Committee of Commerce resolved to inquire a survey and examination be conducted under the US War Department. The purpose was twofold. A line of communication from the Chesapeake Bay on the James and Kanawha rivers and their tributaries to the mouth of the Kanawha River was to be reported back to Congress with Liberty to be presented as a Bill. It was to include a means of transporting military supplies west in case of war. The commercial necessities of the Mississippi River was to be included and considered in this prospect.[38]

In 1873, citizens of West Virginia petitioned the U.S. Congress for aid in the Little Kanawha River's improvement to Congress. Further improvement of the Kanawha River was requested to Congress in that session's Rivers and Harbors bills (8.No.1006) (H. R. No. 3168).[39] Gradually, the continental railway system and the Great Lakes connecting to the upper Mississippi River became Congress' main attention in much of the latter half of the 19th century.[40]

The U.S. Government abandoned the Little Kanawha system of locks and dams in 1937. Eleven commercial boats traveled the river in 1912. Steam packet Louise made daily runs between Parkersburg and Creston. Along with log float operators, as many as ten commercial gasoline craft had operated on the river (Bibbee, F.R. 1928).

Kanawha River dams

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began construction of modern dams on the Kanawha River in the late 1880s. The ten French System roller dams, called Chanoine dams, were completed in 1898. These dams provided year-round commercial navigation on the Kanawha River for 90 miles (140 km) from Boomer to Point Pleasant at the river's mouth. This allowed expansion of the shipyards to include contemporary ocean-going military vessels. In 1921, the General John McE. Hyde was built in Charleston on the Kanawha River by the Charles Ward Engineering Works. It saw action during World War II at Manila Bay, Philippines. Its sister ship, the General Frank M. Coxe, was finished in 1922. It served as an Army transport vessel and was later converted to a cruise ship on San Francisco Bay.

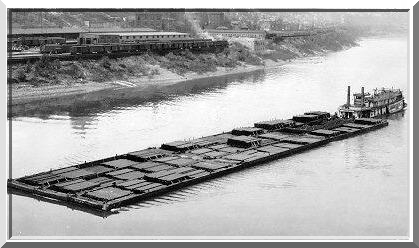

In the 1930s, the ten Chanoine dams were replaced with four High Lift German Roller System dams. This decade saw a considerable increase in military ship building. These dam locations begin at Gallipolis Ferry forming the pool on the lower Kanawha and Ohio rivers, the Winfield Pool, the Marmet Pool and the London Pool to Boomer. During drought, all ensure at least a 12-foot (3.7 m) deep navigation over old shoals, contrasting many of nature's other much deeper channels along the way. In 1989, the USACE began construction of larger and longer lock chambers. Today, most tows no longer need to break-tow to pass through to the next pool. This has allowed much less waiting for a lock through. Some tows can approach 800 feet (240 m), and some nautical authors claim 1,000 feet (300 m) long tows have been made. Smaller pleasure craft can navigate to as far as the Kanawha Falls' public access picnic park and fishing boat ramp while watching for submerged boulders as one might fish above the upper London Pool. The Robert C. Byrd Locks and Dam at Gallipolis Ferry has a public museum with artifacts on display.[41]

Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada.

Satisfying eastern tannery's growing demand for beaver more often came to the "Point" by canoe and raft from the Kanawha region's tributary creeks. Isaac Vanbibber and Daniel Boone's trading post was established about 1790 at the mouth of Crooked Creek at Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Hudson's Trade Post and early landing appears on the 1807 Madison map opposite St Albans. By this decade, the steel trap had increased efficiency as beaver became scarce within two decades. Fewer beaver dams brought drainage of many creek's "lakes". A shift to the state's other natural resources began in ever-increasing export quantity and a change to the riparian zone. The next century brought farmsteads on these naturally "drained" wetland creek bottoms. These settlers saw a slightly different "Topography as the study of place".

A network of local produce exchange was carried between the farmers' landings and major town markets along the rivers. For example, one pair in the 1880s, the paddle wheelers Courier and Express, carried the mail between Wheeling and Parkersburg. These two steamboats passed each other daily, boating also with local produce and passengers.[42]

Kanawha Harbor had a great amount of freight and passenger lay-over after the "Old War" of the 1790s. Kanawha salt production followed by coal and timber floats were moved from West Virginia streams to the populace of other regions. A number of riverside locations were used for early Industrial Revolution keelboat building in the Kanawha region, including at Leon, Ravenswood, Murraysville and on the Little Kanawha River. Earlier 19th century steamboat building and machine repair were located at Wheeling and Parkersburg followed by Point Pleasant and Mason City. Wooden coal barges were built on the Monongahela River near Morgantown, on the Coal River, and some on the Elk River near Charleston before metal barges became the trend. As an example of how local water works progressed, Kanawha Harbor's boat building increased after a horse-drawn logging "tram" with special block and tackle for the hillside harvesting was brought into use and some expansion of Crooked Creek. Later, this tram and other steam machinery were used for collecting timber to be used as railroad ties in the railway construction along the Kanawha River. It was finished about 1880. This brought the small steamboat landings of the farmers along the rivers to use the railway. Many railroading spurs were built throughout West Virginia connecting mines to the riverboats' barge and coal-tipples.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.

Remove ads