Voter-verified paper audit trail

Method of providing feedback to voters From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

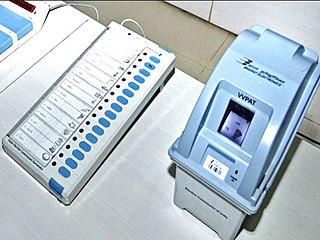

Voter verifiable paper audit trail (VVPAT) or verified paper record (VPR) is a method of providing feedback to voters who use an electronic voting system. A VVPAT allows voters to verify that their vote was cast correctly, to detect possible election fraud or malfunction, and to provide a means to audit the stored electronic results. It contains the name and party affiliation of candidates for whom the vote has been cast. While VVPAT has gained in use in the United States compared with ballotless voting systems without it, hand-marked ballots are used by a greater proportion of jurisdictions.[1]

As a paper-based medium, the VVPAT offers some fundamental advantages over an electronic-only recording medium when storing votes. A paper VVPAT is readable by the human eye and voters can directly interpret their vote. Computer memory requires a device and software which is potentially proprietary. Insecure voting machine[2] records could potentially be changed quickly without detection by the voting machine itself. Auditable paper ballots make it more difficult for voting machines to corrupt records without human intervention. Corrupt or malfunctioning voting machines might store votes other than as intended by the voter unnoticed. A VVPAT allows voters to verify their votes are cast as intended, an additional barrier to changing or destroying votes.

The VVPAT includes a direct recording electronic voting system (DRE), to assure voters that their votes have been recorded as intended and as a means to detect fraud and equipment malfunction. Depending on election laws, the paper audit trail may constitute a legal ballot and therefore provide a means by which a manual vote count can be conducted if a recount is necessary.

In non-document ballot voting systems – both mechanical voting machines and DRE voting machines – the voter does not have an option to review a tangible ballot to confirm the voting system accurately recorded his or her intent. In addition, an election official is unable to manually recount ballots in the event of a dispute. Because of this, critics claim there is an increased chance for electoral fraud or malfunction and security experts, such as Bruce Schneier, have demanded voter-verifiable paper audit trails.[3] Non-document ballot voting systems allow only a recount of the "stored votes". These "stored votes" might not represent the correct voter intent if the machine has been corrupted or suffered malfunction.

As of 2024, VVPAT systems are used in countries including the United States, India,[4] Venezuela,[5] the Philippines,[6] and Bulgaria.[7] In the U.S., 98.5 percent of registered voters live in jurisdictions offering some form of paper ballot, whether hand-marked or VVPAT. Only 1.4 percent use electronic systems with no paper record.[8]

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1897, responding to a question from Rhode Island Governor Charles W. Lippitt about the legality of using the newly-developed McTammany direct-recording voting machine,[9] Associate Justice Horatio Rogers of the Rhode Island Supreme Court noted that a voter casting a vote on such a machine without a written record "has no knowledge through his senses that he has accomplished a result. The most that can be said, is, if the machine worked as intended, then he ... has voted."[10] This observation remains at the center of concerns with ballotless DRE voting machines today.

In 1899, Joseph Gray addressed this problem with a mechanical voting machine that simultaneously recorded votes in its mechanism and punched those votes on a paper ballot that the voter could inspect before dropping it in a ballot box. Gray explained that "in this manner, we have a mechanical check for the tickets [ballots], while the ticket is also a check upon the register [mechanical vote counter]."[11] This check is only effective if there is an audit to compare the paper and mechanical records.

The idea of creating a parallel paper trail for a direct-recording voting mechanism remained dormant for a century until it was rediscovered by Rebecca Mercuri, who suggested essentially the same idea in 1992.[12] The Mercuri method, as some have called it, was refined in her Ph.D. dissertation in October 2000; in her final version, the paper record is printed behind glass so that the voter may not take it or alter it.[13]

The first commercial voting systems to incorporate voter verifiable paper audit trail printers were the Avante Vote Trakker and a retrofit to the Sequoia AVC Edge called the VeriVote Printer.[14] Avante's system saw its first trial use in 2002, and in 2003, the state of Nevada required the use of VVPAT technology statewide and adopted the Sequoia system. It is notable that, in Avante's design, the shield preventing the voter from taking the paper record was an afterthought, while in Sequoia's design, the paper record for successive voters were printed sequentially on a single roll of paper.

Voter-verifiable paper audit trail was first used in an election in India in September 2013 in Noksen (Assembly Constituency) in Nagaland.[15][16] The VVPAT system was introduced in 8 of 543 parliamentary constituencies as a pilot project in the 2014 Indian general election.[17][18][19][20] VVPAT was implemented in Lucknow, Gandhinagar, Bangalore South, Chennai Central, Jadavpur, Raipur, Patna Sahib and Mizoram constituencies.[21][22][23][24][25][26] VVPAT along with EVMs was used on a large-scale for the first time in India,[27] in 10 assembly seats out of 40 in 2013 Mizoram Legislative Assembly election.[28] VVPAT -fitted EVMs was used in entire Goa state in the 2017 assembly elections, the first time that entire state in India saw the implementation of VVPAT.[29][30] A VVPAT system was introduced in all 543 Lok sabha constituencies in the 2019 Indian general election.[31][32]

Case study: U.S. presidential election in Georgia 2020

Summarize

Perspective

In July 2019, after legal challenges and concerns about the security and reliability of its aging electronic voting machines,[33] Georgia officials approved a $107 million contract with Dominion Voting Systems to equip all 159 Georgia counties with new ballot-marking devices that provide a paper ballot for every vote cast (VVPAT). The upgrade was completed in time for the 2020 Georgia Republican and Democratic presidential primaries.

The system proved critical during the general election in November 2020. A razor-thin margin of victory for Joe Biden (0.23 percent or 11,779 votes)—the first by a Democratic presidential candidate in the state since 1992—automatically triggered a statewide audit, made possible by the new auditable paper ballot system. The audit found several human errors at the county level, netting Trump 1,274 votes. At the Trump campaign's request, this was followed by a full statewide hand recount of the paper ballots, which confirmed the result.[34]

Starting in 2002 with the statewide adoption of DREs and as recently as the 2016 election, the lack of a system producing auditable paper ballots would have made a recount impossible. The VVPAT system allowed officials to cross-check electronic results with paper records, confirming the accuracy of the final vote count[35] and refuting claims by President Trump in a January 2, 2021 phone call with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger that the count was inaccurate.

In additional to providing transparency, Georgia's new VVPAT system helped counter a strong disinformation campaign by facilitating a total of three cross-confirming counts—initial vote, audit, and hand recount. This increased voter confidence, providing a reliable method to verify the results during the intense scrutiny of the 2020 election. A survey by the Center for Election Innovation & Research conducted before and after the election found a smaller-than-expected drop in Georgia voters' confidence (from 90% in October 2020 to 85% in January 2021) that their votes would count as intended.[36]

Application

Summarize

Perspective

Various technologies can be used to implement a paper audit trail.

- Attachment of a printer to direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting machines that print paper records stored within the machine. Such designs usually present the record to the voter behind a transparent surface to enable a voter to confirm a printed record matches the electronic ballot. The records can be manually counted and compared to the electronic vote totals in the event of a dispute. The solution linking electronic ballot images and the voter-verified paper record with randomly generated unique voting session identifier is covered by patents issued and pending.[37]

- Attachment of a printer to DRE voting machines that print paper records on special paper with security features. The printed page contains both a plain text record and a simple barcode of the voter's selections. This page is the official ballot that is then fed through a scanner into a locked ballot box so that all originals are saved in case of the need for a recount or audit. The electronic record from the DRE is compared with the barcode scanner record and in case of any discrepancy, the paper ballots are used to determine the official vote, not the electronic record. The voter has the ability to proofread the ballot before it is placed into the scanner/lockbox and have it voided if there is any error, just as has always been possible with existing manual voting systems.

- Attachment of a printer to DRE voting machines that print an encrypted receipt that is either retained by the voter or stored within the machine. If the receipt is retained, the receipts can be manually counted and compared to the electronic vote totals in the event of a dispute. These systems have not been used in elections in the United States.

- Creation of an encrypted audit trail at the same time the electronic ballot is created in a DRE voting machine, a form of witness system. The audit trail can be accessed and compared to the electronic vote totals in the event of a dispute.

- Use of precinct-based optical scan or mark-sense tabulators instead of DREs. In this simple and cost-effective system, voters fill out paper ballots which are then counted electronically by a tabulator at the precinct, similar to the technology used to score standardized tests. Optical scan machines have been in use for decades, and provide a voter-verified audit trail by default. Tabulators can detect overvotes at the poll so that the voter can be given the opportunity to correct a spoiled ballot.

Systems that allow the voters to prove how they voted do not conform to the generally accepted definition of voting by secret ballot, as such proof raises the risk of voter intimidation and vote selling. As such, systems that allow such proof are generally forbidden under the terms of numerous international agreements and domestic laws.

Professor Avi Rubin has testified in front of the United States House Committee on House Administration in favor of voting systems that use a paper ballot and disfavoring systems that use retrofitted VVPAT attachments. He has said on his personal blog that "after four years of studying the issue, I now believe that a DRE with a VVPAT is not a reasonable voting system."[38]

An auditable system, such as that provided with VVPAT, can be used in randomized recounts to detect possible malfunction or fraud. With the VVPAT method, the paper ballot can be treated as the official ballot of record. In this scenario, the ballot is primary and the electronic records are used only for an initial count or, in some cases, if the VVPAT is damaged or otherwise unreadable. In any subsequent recounts or challenges the paper, not the electronic ballot, would be used for tabulation. Whenever a paper record serves as the legal ballot, that system will be subject to the same benefits and concerns of any paper ballot system.

Matt Quinn, the developer of the original Australian DRE system, believes that "There's no reason voters should trust a system that doesn't have [a voter-verified audit trail], and they shouldn't be asked to. Why on earth should [voters] have to trust me – someone with a vested interest in the project's success? A voter-verified audit trail is the only way to 'prove' the system's integrity to the vast majority of electors, who after all, own the democracy."[39]

In India, in an instance VVPAT was helpful in resolving an issue pertaining to a tally of votes in Kancheepuram (State Assembly Constituency) in 2016 Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly election as the number of votes entered in the Form 17C of a polling booth and the total number of votes recorded in the EVM control unit of that booth did not tally.[40] In June 2018, Election Commission of India introduced a built-in-hood on top of the contrast sensor and paper roll that does not soak humidity in all VVPATs to prevent it from excess light and heat.[41][42] In case of a discrepancy between the information on VVPATs and the EVMs, the paper slips of the particular polling station in question are recounted.[43] If the discrepancy persists, the count established by the VVPAT paper slips prevails over the vote count registered on the EVMs.[44]

Challenges and concerns

Summarize

Perspective

Common problems

Common VVPAT problems are:

- Video of voter behavior during an actual election revealed that most voters do not verify their choices by reading the VVPAT.[45]

- Research indicates voters who do check ballot summaries overlook discrepancies.[46]

- A manual VVPAT recount/audit is labor-intensive and expensive, and likely unaffordable to most candidates seeking it.

- And while VVPAT is designed to serve as a check on DRE (Direct Recording Electronic) vote recorders, it relies on the same proprietary programming and electronics to produce the audit trail.

Other hurdles in the implementation of paper audit trails include the performance and authority of the audit. Paper audit systems increase the cost of electronic voting systems, can be difficult to implement, often require specialized external hardware, and can be difficult to use. In the United States twenty-seven states require a paper audit trail by statute or regulation for all direct recording electronic voting machines used in public elections.[47] Another eighteen States don't require them, but use them either statewide or in local jurisdictions.[48]

Security

The introduction of malicious software into a VVPAT system can cause it to intentionally misrecord the voter's selections. This attack could minimize detection by manipulating only a small percentage of the votes or for only lesser known races.[49]

Another security concern is that a VVPAT could print while no voter is observing the paper trail, a form of ballot stuffing.[50] Even if additional votes were discovered through matching to the voters list, it would be impossible to identify legitimate ballots from fraudulent ballots.

Alternatively the printer could invalidate the printed record after the voter leaves and print a new fraudulent ballot. These ballots would be undetectable as invalidated ballots are quite common during elections.[51] Also, VVPAT systems that are technically able to reverse the paper feed could be open to manipulated software overwriting or altering the VVPAT after the voter checks it.

Usability and ergonomics

For the voter, the printed record is "in a different format than the ballot, in a different place, is verified at a different time, and has a different graphical layout with different contrast and lighting parameters."[52] In November 2003 in Wilton, CT, virtually all voters had to be prompted to find and verify their receipt, increasing the time required to vote and the work for the pollworkers. The VVPAT adds to the complexity of voting, already a deterrent to voting.[52]

In addition, a VVPAT component may not be easily usable by poll-workers, many of whom are already struggling with DRE maintenance and use and new elections law requirements. In the 2006 primary election in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, a study found that 9.6 percent of the VVPAT tapes were either destroyed, blank, illegible, missing, taped together or otherwise compromised. In one case the thermal paper was loaded into the printer backwards leaving a blank tape,[53][54] which was not realized by voters who couldn't verify the paper trail. The Cuyahoga Election Review Panel proposed in its final report to remove the opaque doors covering the VVPAT except the ones equipped with equipment for blind voters.[55] In general collecting and counting these printed records can be difficult.[52]

Records printed on continuous rolls of paper is more difficult than counting standard paper ballots or even punch cards.[52]

Privacy

DRE VVPAT systems that print the ballot records out in the order in which they were cast (often known as reel-to-reel systems) raise privacy issues, if the order of voting can also be recorded. VVPAT printers that cut the paper after each ballot to form individual ballots can avoid this concern. If there are multiple voting machines it would be more difficult to match between the full voter list and the VVPATs.

Alternatively, an attacker could watch the order in which people use a particular voting system and note the order of each particular vote he is interested in. If that attacker later obtains the paper ballot records she could compare the two and compromise the privacy of the ballot. This could also lead to vote selling and voter intimidation.[56]

In 2007, Jim Cropcho and James Moyer executed and publicized a proof of concept for this theory. Via a public records request, the two extracted voter identification from pollbooks, and voter preference from VVPATs, for a Delaware County, Ohio, precinct with multiple voting machines. Because both sets of records independently established the order of electronic ballots cast, they directly linked a voter's identification to his or her preference.[57] Over 1.4 million registered voters in ten Ohio counties were affected. The situation was resolved before the next election by omitting the consecutive numbers on Authority To Vote slips from pollbook records. However, similar vulnerabilities may still exist in other states.

Effectiveness

Also problematic is that voters are not required to actually check the paper audit before casting a ballot, which is critical to "verifying" the vote. While the option to look at the paper may provide comfort to an individual voter, the VVPAT does not serve as an effective check on malfunction or fraud unless a statistically relevant number of voters participate.

Accessibility

Current VVPAT systems are not usable by some disabled voters. Senator Christopher Dodd (D-CT) testified before the United States Senate Committee on Rules and Administration at a June 2005 hearing on Voter Verification in Federal Elections "The blind cannot verify their choices by means of a piece of paper alone in a manner that is either independent or private. Nor can an individual who has a mobility disability, such as hand limitations, verify a piece of paper alone, if that individual is required to pick up and handle the paper."[58]

Reliability

VVPAT systems can also introduce increased concern over reliability. Professor Michael Shamos points out that "Adding a paper printing device to a DRE machine naturally adds another component that can fail, run out of ink, jam or run out of paper. If DREs are alleged already to be prone to failure, adding a paper trail cannot improve that record."[59] In Brazil in 2003, where a small number of precincts had installed paper trails, failure of the printers delayed voters by as much as 12 hours, a figure that would be catastrophic in the U.S.[60]

Current implementation of VVPAT systems use thermal printers to print their paper ballot records. Ballot records printed on the thermal paper will fade with time. Also, heat applied to the paper before or after the election can destroy the printing.[52]

Implementation

It can be significantly more difficult to implement a VVPAT as an after-the-fact feature. For jurisdictions currently using DRE voting machines that lack a VVPAT, implementation can be expensive to add and difficult to implement due to the specialized external hardware required. To add a VVPAT component to a DRE machine, a jurisdiction would be required to purchase the system designed by the vendor of the DRE machine with a no bid, sole source purchase contract. That assumes the vendor has designed a component that is compatible with the DRE machine in use. The vendor may not have developed a VVPAT component that is compatible with the DRE machine in use, thus requiring the jurisdiction to purchase an entirely new voting system.

For jurisdictions not currently using DRE machines, the introduction of a new voting system that includes a VVPAT component would have less implementation challenges. Some implementations of the VVPAT place a high cognitive burden on the voter and are extraordinarily error prone.[61]

Legal questions

One important question of VVPAT systems is regarding the time of the audit. Some have suggested that random audits of direct recording electronic voting machines be performed on Election Day to protect against machine malfunction. However, the partial tallying of votes before the polls have closed could create a problem similar to the occurrence in American national elections where a winner is declared based on East Coast results long before polls have closed on the West Coast. In addition, the partial tallying of votes before the polls have closed may be illegal in some jurisdictions. Others have suggested that random audits of direct recording electronic voting machines be performed after the election or only in the event of a dispute.

In the event an audit is performed after the election and a discrepancy is discovered between the ballot count and the audit count it is unclear which count is the authoritative count. Some jurisdictions have statutorily defined the ballot as the authoritative count leaving the role of an audit in question. Because VVPAT is a recent addition to direct record voting systems the authority question remains unclear.

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.