Loading AI tools

1855 and 1871 nonsense poem by Lewis Carroll From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Jabberwocky" is a nonsense poem written by Lewis Carroll about the killing of a creature named "the Jabberwock". It was included in his 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The book tells of Alice's adventures within the back-to-front world of the Looking-Glass world.

In an early scene in which she first encounters the chess piece characters White King and White Queen, Alice finds a book written in a seemingly unintelligible language. Realising that she is travelling through an inverted world, she recognises that the verses on the pages are written in mirror-writing. She holds a mirror to one of the poems and reads the reflected verse of "Jabberwocky". She finds the nonsense verse as puzzling as the odd land she has passed into, later revealed as a dreamscape.[1]

"Jabberwocky" is considered one of the greatest nonsense poems written in English.[2][3] Its playful, whimsical language has given English nonsense words and neologisms such as "galumphing" and "chortle".

A decade before the publication of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and the sequel Through the Looking-Glass, Carroll wrote the first stanza to what would become "Jabberwocky" while in Croft-on-Tees, where his parents resided. It was printed in 1855 in Mischmasch, a periodical he wrote and illustrated for the amusement of his family. The piece, titled "Stanza of Anglo-Saxon Poetry", reads:

Twas bryllyg, and þe slythy toves

Did gyre and gymble in þe wabe:

All mimsy were þe borogoves;

And þe mome raths outgrabe.

The stanza is printed first in faux-mediaeval lettering as a "relic of ancient Poetry" (in which þe is a form of the word the) and printed again "in modern characters".[4] The rest of the poem was written during Carroll's stay with relatives at Whitburn, near Sunderland. The story may have been partly inspired by the local Sunderland area legend of the Lambton Worm[5][6] and the tale of the Sockburn Worm.[7]

The concept of nonsense verse was not original to Carroll, who would have known of chapbooks such as The World Turned Upside Down[8] and stories such as "The Grand Panjandrum". Nonsense existed in Shakespeare's work and was well-known in the Brothers Grimm's fairytales, some of which are called lying tales or lügenmärchen.[9] Biographer Roger Lancelyn Green suggested that "Jabberwocky" was a parody of the German ballad "The Shepherd of the Giant Mountains",[10][11][12] which had been translated into English by Carroll's cousin Menella Bute Smedley in 1846.[11][13] Historian Sean B. Palmer suggests that Carroll was inspired by a section from Shakespeare's Hamlet, citing the lines: "The graves stood tenantless, and the sheeted dead / Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets" from Act I, Scene i.[14][15]

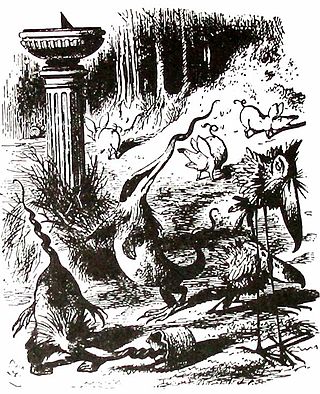

John Tenniel reluctantly agreed to illustrate the book in 1871,[16] and his illustrations are still the defining images of the poem. The illustration of the Jabberwock may reflect the contemporary Victorian obsession with natural history and the fast-evolving sciences of palaeontology and geology. Stephen Prickett notes that in the context of Darwin and Mantell's publications and vast exhibitions of dinosaurs, such as those at the Crystal Palace from 1854, it is unsurprising that Tenniel gave the Jabberwock "the leathery wings of a pterodactyl and the long scaly neck and tail of a sauropod."[16]

"Jabberwocky"

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

"Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!"

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

"And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!"

He chortled in his joy.

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

from Through the Looking-Glass, and

What Alice Found There (1871)

Many of the words in the poem are playful nonce words of Carroll's own invention, without intended explicit meaning. When Alice has finished reading the poem she gives her impressions:

"It seems very pretty," she said when she had finished it, "but it's rather hard to understand!" (You see she didn't like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn't make it out at all.) "Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don't exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that's clear, at any rate."[1]

This may reflect Carroll's intention for his readership; the poem is, after all, part of a dream. In later writings he discussed some of his lexicon, commenting that he did not know the specific meanings or sources of some of the words; the linguistic ambiguity and uncertainty throughout both the book and the poem may largely be the point.[17]

In Through the Looking-Glass, the character of Humpty Dumpty, in response to Alice's request, explains to her the non-sense words from the first stanza of the poem, but Carroll's personal commentary on several of the words differ from Humpty Dumpty's. For example, following the poem, a "rath" is described by Humpty Dumpty as "a sort of green pig".[18] Carroll's notes for the original in Mischmasch suggest a "rath" is "a species of Badger" that "lived chiefly on cheese" and had smooth white hair, long hind legs, and short horns like a stag.[19] The appendices to certain Looking Glass editions state that the creature is "a species of land turtle" that lived on swallows and oysters.[19] Later critics added their own interpretations of the lexicon, often without reference to Carroll's own contextual commentary. An extended analysis of the poem and Carroll's commentary is given in the book The Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner.

In 1868 Carroll asked his publishers, Macmillan, "Have you any means, or can you find any, for printing a page or two in the next volume of Alice in reverse?" It may be that Carroll was wanting to print the whole poem in mirror writing. Macmillan responded that it would cost a great deal more to do, and this may have dissuaded him.[19]

In the author's note to the Christmas 1896 edition of Through the Looking-Glass Carroll writes, "The new words, in the poem Jabberwocky, have given rise to some differences of opinion as to their pronunciation, so it may be well to give instructions on that point also. Pronounce 'slithy' as if it were the two words, 'sly, thee': make the 'g' hard in 'gyre' and 'gimble': and pronounce 'rath' to rhyme with 'bath'."[20]

In the Preface to The Hunting of the Snark, Carroll wrote, "[Let] me take this opportunity of answering a question that has often been asked me, how to pronounce 'slithy toves'. The 'i' in 'slithy' is long, as in 'writhe', and 'toves' is pronounced so as to rhyme with 'groves'. Again, the first "o" in "borogoves" is pronounced like the 'o' in 'borrow'. I have heard people try to give it the sound of the 'o' in 'worry'. Such is Human Perversity."[21]

Though the poem contains many nonsensical words, English syntax and poetic forms are observed, such as the quatrain verses, the general ABAB rhyme scheme and the iambic meter.[30] Linguist Peter Lucas believes the "nonsense" term is inaccurate. The poem relies on a distortion of sense rather than "non-sense", allowing the reader to infer meaning and therefore engage with narrative while lexical allusions swim under the surface of the poem.[10][31]

Marnie Parsons describes the work as a "semiotic catastrophe", arguing that the words create a discernible narrative within the structure of the poem, though the reader cannot know what they symbolise. She argues that Humpty Dumpty tries, after the recitation, to "ground" the unruly multiplicities of meaning with definitions, but cannot succeed as both the book and the poem are playgrounds for the "carnivalised aspect of language". Parsons suggests that this is mirrored in the prosody of the poem: in the tussle between the tetrameter in the first three lines of each stanza and trimeter in the last lines, such that one undercuts the other and we are left off balance, like the poem's hero.[17]

Carroll wrote many poem parodies such as "Twinkle, twinkle little bat", "You Are Old, Father William" and "How Doth the Little Crocodile?" Some have become generally better known than the originals on which they are based, and this is certainly the case with "Jabberwocky".[10] The poems' successes do not rely on any recognition or association of the poems that they parody. Lucas suggests that the original poems provide a strong container but Carroll's works are famous precisely because of their random, surreal quality.[10] Carroll's grave playfulness has been compared with that of the poet Edward Lear; there are also parallels with the work of Gerard Manley Hopkins in the frequent use of soundplay, alliteration, created-language and portmanteau. Both writers were Carroll's contemporaries.[17]

"Jabberwocky" has been translated into 65 languages.[32] The translation might be difficult because the poem holds to English syntax and many of the principal words of the poem are invented. Translators have generally dealt with them by creating equivalent words of their own. Often these are similar in spelling or sound to Carroll's while respecting the morphology of the language they are being translated into. In Frank L. Warrin's French translation, "'Twas brillig" becomes "Il brilgue". In instances like this, both the original and the invented words echo actual words of Carroll's lexicon, but not necessarily ones with similar meanings. Translators have invented words which draw on root words with meanings similar to the English roots used by Carroll. Douglas Hofstadter noted in his essay "Translations of Jabberwocky", the word 'slithy', for example, echoes the English 'slimy', 'slither', 'slippery', 'lithe' and 'sly'. A French translation that uses 'lubricilleux' for 'slithy', evokes French words like 'lubrifier' (to lubricate) to give an impression of a meaning similar to that of Carroll's word. In his exploration of the translation challenge, Hofstadter asks "what if a word does exist, but it is very intellectual-sounding and Latinate ('lubricilleux'), rather than earthy and Anglo-Saxon ('slithy')? Perhaps 'huilasse' would be better than 'lubricilleux'? Or does the Latin origin of the word 'lubricilleux' not make itself felt to a speaker of French in the way that it would if it were an English word ('lubricilious', perhaps)? ".[33]

Hofstadter also notes that it makes a great difference whether the poem is translated in isolation or as part of a translation of the novel. In the latter case the translator must, through Humpty Dumpty, supply explanations of the invented words. But, he suggests, "even in this pathologically difficult case of translation, there seems to be some rough equivalence obtainable, a kind of rough isomorphism, partly global, partly local, between the brains of all the readers".[33]

In 1967, D.G. Orlovskaya wrote a popular Russian translation of "Jabberwocky" entitled "Barmaglot" ("Бармаглот"). She translated "Barmaglot" for "Jabberwock", "Brandashmyg" for "Bandersnatch" while "myumsiki" ("мюмзики") echoes "mimsy". Full translations of "Jabberwocky" into French and German can be found in The Annotated Alice along with a discussion of why some translation decisions were made.[34] Chao Yuen Ren, a Chinese linguist, translated the poem into Chinese[35] by inventing characters to imitate what Rob Gifford of National Public Radio refers to as the "slithy toves that gyred and gimbled in the wabe of Carroll's original".[36] Satyajit Ray, a film-maker, translated the work into Bengali[37] and concrete poet Augusto de Campos created a Brazilian Portuguese version. There is also an Arabic translation[38][39] by Wael Al-Mahdi, and at least two into Croatian.[40] Multiple translations into Latin were made within the first weeks of Carroll's original publication.[41] In a 1964 article, M. L. West published two versions of the poem in Ancient Greek that exemplify the respective styles of the epic poets Homer and Nonnus.[42]

| Bulgarian (Lazar Goldman & Stefan Gechev) |

Danish 1 (Mogens Jermiin Nissen) Jabberwocky |

Danish 2 (Arne Herløv Petersen) Kloppervok |

|

|

|

| Esperanto (Marjorie Boulton) La Ĵargonbesto |

Turkish (Nihal Yeğinobalı) Ejdercenkname |

Finnish 1 (Kirsi Kunnas & Eeva-Liisa Manner, 1974) Pekoraali |

|

|

|

| Finnish 2 (Matti Rosvall, 1999) Jabberwocky[46] |

Finnish 3 (Alice Martin, 2010) Monkerias |

French (Frank L. Warrin) |

|

|

|

| Georgian (Giorgi Gokieli) ტარტალოკი |

German (Robert Scott) |

Hebrew 1 (Aharon Amir) פִּטְעוֹנִי |

|

|

|

| Hebrew 2 (Rina Litvin) גֶּבֶרִיקָא |

Icelandic (Valdimar Briem) Rausuvokkskviða |

Irish (Nicholas Williams) An Gheabairleog |

|

|

|

| Italian (Adriana Crespi) Il ciarlestrone |

Latin (Hassard H. Dodgson) Gaberbocchus |

Polish (Janusz Korwin-Mikke) Żabrołak |

|

|

|

| Portuguese 1 (Augusto de Campos, 1980) Jaguadarte[48] |

Portuguese 2 (Oliveira Ribeiro Neto, 1984) Algaravia[49] |

Portuguese 3 (Ricardo Gouveia) Blablassauro[49] |

|

|

|

| Russian (Dina Orlovskaya) |

Spanish 1 (Ulalume González de León) El Jabberwocky |

Spanish 2 (Adolfo de Alba) El Jabberwocky |

|

|

|

| Spanish 3 (Ramón Buckley, 1984) El Fablistanón |

Welsh (Selyf Roberts) Siaberwoci |

American Sign Language (ASL)

(Eric Malzkuhn, 1939) |

|

|

Due to no written language in ASL, view video to see translation of Jabberwocky. (Performed in 1994)

See this link for explanation of techniques used by Eric Malzkuhn |

According to Chesterton and Green and others, the original purpose of "Jabberwocky" was to satirise both pretentious verse and ignorant literary critics. It was designed as verse showing how not to write verse, but eventually became the subject of pedestrian translation or explanation and incorporated into classroom learning.[50] It has also been interpreted as a parody of contemporary Oxford scholarship and specifically the story of how Benjamin Jowett, the notoriously agnostic Professor of Greek at Oxford, and Master of Balliol, came to sign the Thirty-Nine Articles, as an Anglican statement of faith, to save his job.[51] The transformation of audience perception from satire to seriousness was in a large part predicted by G. K. Chesterton, who wrote in 1932, "Poor, poor, little Alice! She has not only been caught and made to do lessons; she has been forced to inflict lessons on others."[52]

It is often now cited as one of the greatest nonsense poems written in English,[3][2] the source for countless parodies and tributes. In most cases the writers have changed the nonsense words into words relating to the parodied subject, as in Frank Jacobs's "If Lewis Carroll Were a Hollywood Press Agent in the Thirties" in Mad for Better or Verse.[53] Other writers use the poem as a form, much like a sonnet, and create their own words for it as in "Strunklemiss" by Shay K. Azoulay[54] or the poem "Oh Freddled Gruntbuggly" recited by Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz in Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a 1979 book which contains numerous other references and homages to Carroll's work.[55]

Some of the words that Carroll created, such as "chortled" and "galumphing", have entered the English language and are listed in the Oxford English Dictionary. The word "jabberwocky" itself has come to refer to nonsense language.

In American Sign Language, Eric Malzkuhn invented the sign for "chortled". It unintentionally caught on and became a part of American Sign Language's lexicon as well.[57]

A song called "Beware the Jabberwock" was written for Disney's 1951 animated film Alice in Wonderland sung by Stan Freberg, but it was discarded, replaced with "'Twas Brillig", sung by the Cheshire Cat, that includes the first stanza of "Jabberwocky".

The Alice in Wonderland sculpture in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, has at its base, among other inscriptions, a line from "Jabberwocky".[58]

The British group Boeing Duveen and The Beautiful Soup released a single (1968) called "Jabberwock" based on the poem.[59] Singer and songwriter Donovan put the poem to music on his album HMS Donovan (1971).

The poem was a source of inspiration for Jan Švankmajer's 1971 short film Žvahlav aneb šatičky slaměného Huberta (released as Jabberwocky in English) and Terry Gilliam's 1977 feature film Jabberwocky.

In 1972, the American composer Sam Pottle put the poem to music.[60] The stage musical Jabberwocky (1973) by Andrew Kay, Malcolm Middleton and Peter Phillips, follows the basic plot of the poem.[61][62] Keyboardists Clive Nolan and Oliver Wakeman released a musical version Jabberwocky (1999) with the poem read in segments by Rick Wakeman.[63] British contemporary lieder group Fall in Green set the poem to music for a single release (2021) on Cornutopia Music.[64][65]

In 1978, the musical group Ambrosia included the text of Jabberwocky in the lyrics of "Moma Frog" (credited to musicians Puerta, North, Drummond, and Pack) on their debut album Ambrosia.[66]

In 1980 The Muppet Show staged a full version of "Jabberwocky" for TV viewing, with the Jabberwock and other creatures played by Muppets closely based on Tenniel's original illustrations. According to Jaques and Giddens, it distinguished itself by stressing the humor and nonsense of the poem.[67]

The Jabberwock appears in Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland (2010), voiced by Christopher Lee, and is referred to as "The Jabberwocky". An abridged version of the poem is spoken by the Mad Hatter (played by Johnny Depp).[68][69]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.