Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Venezuelan independence

Emancipation process between 1810 and 1823 in Venezuela From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Venezuelan Independence was the juridical-political process that put an end to the ties between the Captaincy General of Venezuela and the Spanish Empire. It also implied the replacement of the absolute monarchy by the republic as the form of government in Venezuela.

The independence of Venezuela produced the armed conflict known as the Venezuelan War of Independence between the independence army or Patriotas ("patriots") and the royalist army or Realistas ("royalists").

On July 5, 1811, the independence declaration is signed. That day is celebrated in Venezuela as its national day. On that date formally, through the document "Acta de Declaración de Independencia", Venezuela separates from Spain. The Sociedad Patriótica composed by Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda was the pioneer in the push for Venezuela's separation from the Spanish crown.[1]

The historical period between 1810 and 1830 has been divided by Venezuelan historiography into four parts: First Republic (1810 -1812), Second Republic (1813 -1814), Third Republic (1817-1819), and Gran Colombia (1819 -1830).

Remove ads

Causes

Influential factors include the desire for power of the creole social groups that possessed social and economic status but not political, the discontent of the population due to mismanagement and the rise of taxes,[2] the introduction of the ideas of Encyclopedism, the Enlightenment, the Declaration of Independence of the United States, the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, and the reign of Joseph I of Spain.

Remove ads

Background

The first independence attempts took place in Venezuela at the end of the 18th century. The first of them tries twice in 1806 to invade the Venezuelan territory through La Vela de Coro, led by General Francisco de Miranda, with an armed expedition coming from Haiti. Their incursions ended in failures due to the religious preaching against them and the indifference of the population.

The Conjuración de los Mantuanos was a movement that broke out in Caracas in 1808. The Mantuanos, who constituted the most powerful social group of the society, led an attempt to constitute a Governing Board to govern the destiny of the Captaincy General of Venezuela as a result of the invasion of Spain by Napoleon.

Remove ads

First Republic

Summarize

Perspective

Revolution of April 19, 1810

The first republic corresponds to the period between April 19, 1810, and July 30, 1812, when the Supreme Junta of Caracas peacefully replaces the Spanish authorities.[3]

Captain General Vicente Emparan was forced to resign his post on April 19, 1810, by the cabildo of Caracas. That same afternoon the cabildo constituted itself as the Supreme Conservative Junta of the Rights of Fernando VII.

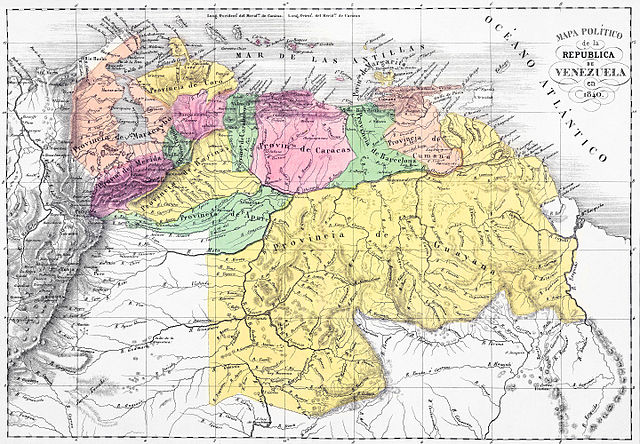

The Supreme Junta of Caracas sought the adhesion of the other provinces of the Captaincy General of Venezuela to the movement. Favorable pronouncements were given in Cumaná and Barcelona on April 27, Margarita on May 4, Barinas on May 5, Mérida on September 16, and Trujillo on October 9.[4]

Guayana spoke out on May 11 in favor of the Supreme Junta, but upon learning on June 3 of the installation in Spain of the Supreme Central and Governing Junta of Spain and the Indies, it recognized the latter as the legitimate authority and distanced itself from the Caracas revolution.[4] The Provinces of Coro and Maracaibo remained loyal to the Council of Regency.[4]

Supreme Congress of Venezuela

The character of the Supreme Junta of Caracas as "Conservative of the rights of Ferdinand VII" did not allow it to go beyond the autonomy proclaimed on April 19. For that reason, the Junta called for elections to install a Constituent Congress before which it could decline its powers and decide the future fate of the states.

The call for the Congress was made in June. It was accepted by the provinces of Caracas, Barinas, Cumaná, Barcelona, Mérida, Margarita and Trujillo; but not by the provinces of Maracaibo, Coro and Guayana.

The elections were held between October and November 1810. The electoral regulations were census-based as they gave the vote to free men, over 25 years of age (or over 21 if married) and owners of 2000 pesos in real or personal property.[5] There was no vote for women, slaves, and those lacking wealth.[5] The regulations also provided that elections were to be held in two stages: first, the voters appointed the electors of the parish; and then, these electors, meeting in an electoral assembly in the capital of the province, appointed the representatives to Congress, at the rate of one deputy for every 20,000 inhabitants.[5]

After the elections, 44 deputies were elected to Congress. The provinces were represented as follows: Caracas 24 deputies; Barinas 9; Cumaná 4; Barcelona 3; Mérida 2; Trujillo 1; Margarita 1.

The Supreme Congress of Venezuela was installed on March 2, 1811, in the house of the Count of San Javier (present "El Conde" corner in Caracas).[5] On March 5, 1811, the Supreme Junta of Caracas ceased its functions.[4]

Patriotic Society

With the founding of the Sociedad de Agricultura y Economía, it did not take long for this organization to become the main promoter of the break with Spain. Among its members were José Félix Ribas, Francisco José Ribas, Antonio Muñoz Tébar, Vicente Salias, and Miguel José Sanz. At its sessions they discussed economics, politics, civil, religious and military matters. It had up to 600 members in Caracas alone and branches in Barcelona, Barinas, Valencia and Puerto Cabello.[6] The newspaper Patriota Revolucionario, directed by Salias and Muñoz Tébar, was its informative organ since June 1811.

The incorporation of the Generalissimo Francisco de Miranda and the young Simón Bolívar, gave the society a revolutionary character. Criticism of the colonial regime, dissemination of separatist ideas, and pressure on the Congress to declare independence were the most important actions of the Patriotic Society.

Declaration of Independence

In the Supreme Congress of Venezuela there were two warring factions: the separatists and the fidelists. The separatists were in favor of Venezuela's independence, while the fidelists were loyal to King Ferdinand VII.

As the sessions of the Congress went on, the idea of independence gained followers in the heart of the Congress. Many deputies supported it with passionate pleadings, others with historical arguments.

On July 2, 1811, a motion on independence was presented in Congress.[7] On July 3, the debate began in Congress.[7] On July 5, the vote was taken.[7] Independence was approved with 40 votes in favor. Immediately, the president of the Congress, Congressman Juan Antonio Rodriguez, announced that "The absolute Independence of Venezuela [was] solemnly declared."[7]

Francisco de Miranda and other members of the Patriotic Society led a mass of people through the streets and squares of Caracas, acclaiming independence and freedom.[7] Juan Escalona, who presided over the first independence triumvirate, issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Caracas letting them know that the Congress had voted for absolute independence.[7]

The deputies agreed to call the new republic as Confederación Americana de Venezuela and appointed a commission to decide on the flag and the drafting of a constitution. The deputy Juan Germán Roscio and the secretary of the Congress, Francisco Isnardi, drafted the Act of Declaration of Independence.[7] It was approved by the deputies on July 7.[7]

On July 13, 1811, the flag of Venezuela was approved, which was based on the design made by Francisco de Miranda in 1806. On July 14, in a public and solemn act, this flag was hoisted for the first time.

On December 21, 1811, the Congress approved the Federal Constitution of the States of Venezuela of 1811.[5] On February 15, 1812, the Congress suspended its sessions and agreed to move to Valencia, designating it Federal City on March 1 that same year, when it resumed its sessions.[5]

Takeover of Valencia

On July 11, 1811, six days after the Declaration of Independence, two insurrections broke out, the asonada de la Sabana del Teque of the Canary Islanders in Caracas[8] —which was quickly brought under control—and the insurrection of Nuestra Señora de la Anunciación de la Nueva Valencia del Rey. The Mantuanos, who did not tolerate the patriots, appointed the Marquis del Toro as commander to confront the Valencian uprising, but on July 15 he was defeated. Then, Francisco de Miranda, at the age of 61, was named Commander in Chief of the Army and left with his troops for Valencia on the 19th. The actions in the streets and squares were hard-fought. Francisco de Miranda ordered to attack the strongest positions of the rebels and on July 23, the republicans took the city.

Fall of the First Republic

On March 26, 1812, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, an earthquake destroyed Caracas causing great damage and the death of about 20,000 people. That same year, Bolívar lost control of Puerto Cabello and Francisco de Miranda capitulated in San Mateo before the royalist chief Domingo Monteverde, signing an agreement that consisted in the surrender of weapons by the patriots. In exchange, the royalists would respect people and goods.

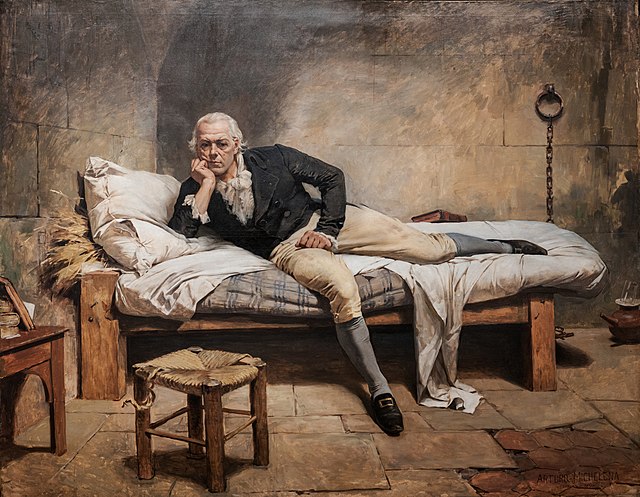

When Miranda went to embark in La Guaira, he was arrested—along with 8 other chiefs—by his former comrades, among whom was the young Simón Bolívar. The prisoners were accused of squandering public funds and then handed over to the royalists. Miranda was imprisoned in Puerto Cabello, then transferred to Puerto Rico and finally to the Arsenal de la Carraca, in Cádiz, where he died in 1816.

Remove ads

Second Republic

Summarize

Perspective

The second republic corresponds to the period between August 1813 and December 1814 and is known as the "War to the Death" period.[3][9]

Once the first Republic was over, the main political and military leaders of the Independence went into exile. Bolívar writes the Cartagena Manifesto where he analyzes the reasons for the failure of the republic and the future of the countries participating in this process, which would later form Gran Colombia. It was written in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia), on December 15, 1812. Among the political, economic, social and natural causes mentioned by Bolívar are:

- The use of the federal system, which Bolívar considers weak for the time.

- Poor administration of public revenues.

- The earthquake of Caracas of 1812.

- The impossibility of establishing a permanent army.

- The contrary influence of the Catholic Church.

On the royalist side, Monteverde, conceited by his success, refuses to hand over power to General Fernando Mijares, who arrived in Puerto Cabello from Puerto Rico and was appointed Captain General by the Regency. In breach of the agreement with Miranda, he began a repression against the patriots in order to prepare the ground for the execution of his plans to invade the Republic of New Granada, which had been declared independent from Spanish power. Knowing of his intentions, Bolívar requested his incorporation to the New Granada army and logistical support to later initiate the military operations of what is known in history as the Admirable Campaign.

On January 8, 1813, he occupied the city of Ocaña—the second in importance in Norte de Santander, after Cúcuta—after having left the free passage in the Magdalena Medio, thus obtaining the navigation between Bogotá and Cartagena. On February 16, he set sail for Cúcuta as there was danger due to the presence of Ramón Correa and his royalist forces. On his way, he defeated an enemy force that was blocking his way at La Aguada. On the 28th of the same month took place what today is known as the Battle of Cúcuta, which gave independence to this city. The Libertador requested help from the neo-Granadian government through the Cartagena Manifesto, which was conceived for the actions he had already carried out in that country.

In the first six months of 1813, the resistance of the royalists collapses. Monteverde is defeated and wounded. He withdraws to Puerto Cabello, where his soldiers depose him from command. The war continues with two parallel campaigns, unconnected but effective, one from the East, commanded by general Santiago Mariño, known as the Eastern Campaign, and another from the West, commanded by Bolívar, known as Admirable Campaign. Cumaná is liberated on August 3, 1813, by Mariño; Bolívar enters Caracas on August 6.

The reconquest of Caracas by the republicans is for historians the milestone that marks the beginning of what has been called the Second Republic. From Caracas, Bolivar proclaims "War to the Death with the extermination of the Spanish race." The Municipality of Caracas confers Bolivar the title of "El Libertador" ("The Liberator") and "General in Chief of the Republican Army". The following year he is named Supreme Chief. The military situation is complicated by the appearance of José Tomás Boves, Asturian, who organizes an army that fights on the side of the royalists and revolts the black or mestizo population against the Venezuelan whites, that is to say, those who lead the independence process. In the opinion of some historians, Boves took advantage of the social resentment existing in this group.

As of February 1814, a series of encounters between patriots and royalists took place in an area from Lago de Valencia to San Mateo in what is known as the Valles de Aragua. In the high house of the San Mateo hacienda, property of Simón Bolívar, the park was placed—the custody of which was entrusted to Captain Antonio Ricaurte and a small troop of 50 soldiers. During the royalist attack, Francisco Tomás Morales took possession of the sugar mill while one of his columns—going down the Los Cucharos row—took the "high house". The park was not captured by that column because it was prevented by its custodian, Captain Antonio Ricaurte, who upon seeing royalist troops in a position to capture that deposit set fire to the gunpowder and blew it up on March 25, 1814, with which he and those who were inside the enclosure perished. Bolivar took advantage of the momentary disorder that occurred among the attackers and launched a counterattack, with which he recaptured the "high house". The statue that immortalizes Ricaurte's heroic gesture in the "Ingenio Bolivar in San Mateo" is a work of the sculptor Lorenzo Gonzalez. In 1814, bloody battles, reprisals against the civilian population of both sides, and the siege of the cities took place. The population of Caracas, threatened by the imminent arrival of Boves, had to flee to the east. Historians mark the battle of Maturín, on December 11, 1814, as the end of the Second Republic.

Once the Admirable Campaign was finished with the entrance to Caracas, Bolivar re-opened operations against the Spanish reaction that soon made itself felt in great part of the country. From Caracas, he sent lieutenant colonels Tomás Montilla to the plains of Calabozo that were threatened by Boves and Vicente Campo Elías to pacify Valles del Tuy, where a rebellion had broken out. Boves defeated an advance guard of Montilla in the siege of Santa Catalina, after which he retreated to Caracas, and Boves entered Calabozo without opposition. In Valles del Tuy, Campo Elías arrives at Ocumare del Tuy on August 26 and in a short time achieves the pacification of the region after which he returns to Caracas. In the capital, he receives orders to go to Calabozo to support Montilla, which results in the defeat of Boves in Mosquiteros on October 14.

Bolivar goes to Valencia with Urdaneta's column where he makes a concentration of troops and divides them into 3 columns: the first commanded by Garcia de Serna to Barquisimeto against the Indian Reyes Vargas, the second led by Atanasio Girardot to Puerto Cabello by the road of Aguas Calientes, and the third by Rafael Urdaneta also to Puerto Cabello but by the road of San Esteban. García de Cerna triumphs over Reyes Vargas in Cerritos Blancos while in Puerto Cabello, Urdaneta and Girardot took the fortresses of Vigía alta, Vigía baja, and the outer town. Monteverde receives reinforcements and launches an offensive on Valencia, Bolívar waits for him in Naguanagua and on September 30, defeats him in the battle of Bárbula. The royalists are defeated again in the battle of Trincheras, on October 3. Monteverde withdraws to Puerto Cabello and Bolívar returns to Caracas after sending Urdaneta against Coro.

The defeat of the first Venezuelan Republic in 1812 left in the Libertador the deepest mark, but above all, the deepest lesson about the cardinal importance that unity had for the triumph of the revolution. "Our division and not the Spanish arms turned us to slavery," he had written in his famous Cartagena Manifesto, taking stock of those years. The Admirable Campaign began on February 28, 1813, with the Battle of Cúcuta against Colonel Ramón Correa where Field Marshal Ribas delivered the decisive blow with a bayonet charge to the center of the royalist lines.[11]

The Libertador did not forget that the first and second Republics had collapsed because the revolution had been oriented exclusively to the elimination of personal privileges or privileges of a feudal nature, and to the proscription of noble titles for the exclusive benefit of the rich Venezuelan or neo-Granadian landowners; without taking into account at all the mass of slaves or poor peasants who constituted the bulk of the pro-independence army.

"Nuestras armas, por siempre triunfales, humillaron al fiero español, del clarín a las voces marciales que oyó en sus montañas la tierra del sol. Coronó nuestras cumbres de gloria cuando Ribas la espada blandió, y a su homérico afán La Victoria con sangre opresora sus campos regó." (in Eng: "Our weapons, forever triumphant, humbled the fierce Spaniard, from the bugle to the martial voices that heard in its mountains the land of the sun. Crowned our summits of glory when Ribas brandished the sword, and to his homeric zeal La Victoria with blood of the oppressors its fields sprayed")[12]

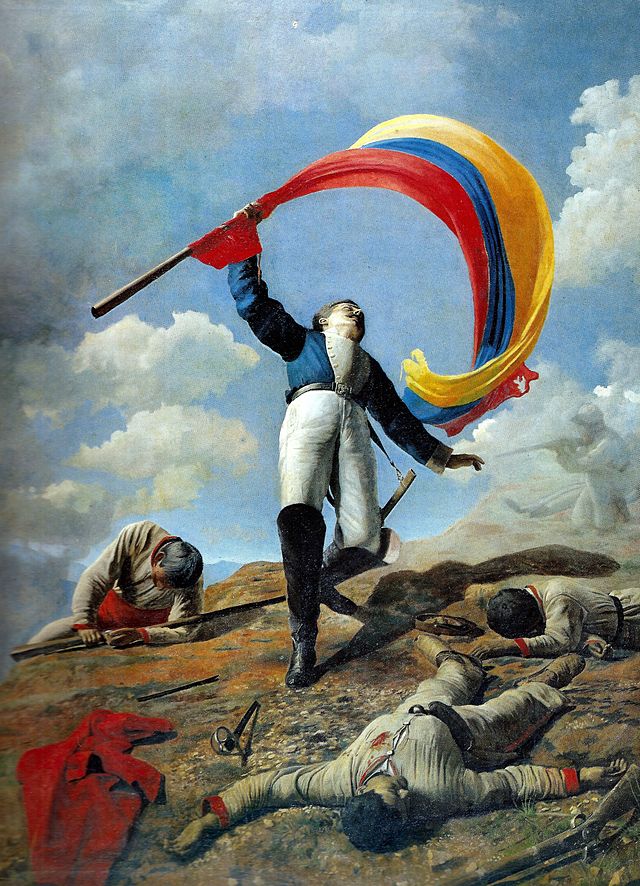

Decree of War to the Death

Colonel Atanasio Girardot joined Simón Bolívar in the so-called Admirable Campaign of the Libertador and fought gallantly at the head of several battalions that managed to occupy the cities of Trujillo and Mérida. In Bolívar's advance towards Caracas, Girardot was in charge of the rearguard from Apure, until reaching him near the city of Naguanagua, next to the hill of Bárbula, where they were to confront the royalist army commanded by Domingo Monteverde. On August 26, 1813, Bolívar personally took charge of the siege against the Puerto Cabello square. On September 16, enemy reinforcements arrived, so Bolívar decided to retreat to the town of Naguanagua. Faced with the patriot retreat, the royalist Monteverde mobilized his troops to the site of Las Trincheras, sending a column of men to take position on the heights of the Bárbula hacienda. Bolívar decided to send on September 30 the troops of Girardot, Urdaneta and D'Elhuyar, who finally managed to dislodge the royalists, but paying a high price, with the sacrifice of Colonel Girardot, who died when he was hit by a rifle bullet while trying to fix the national flag on the conquered height, during the Battle of Bárbula.

The decree of War to the Death was a declaration made by Simón Bolívar on June 15, 1813, in the Venezuelan city of Trujillo. As expressed by the Libertador, it was created as a response to several crimes and massacres carried out by Spanish soldiers after the fall of the First Republic, against thousands of republicans. The aim of the document was to change public opinion about the Venezuelan war of liberation, so that instead of being seen as a mere civil war in one of the colonies of Spain, it would be seen as an international war between two countries, Venezuela and Spain.

It proclaimed that all Spanish persons who did not actively participate in favor of independence would be killed, and that all Americans would be pardoned, even if they cooperated (passively) with the Spanish. The "War to the Death" was practiced by both sides. Thus, between 1815 and 1817, several distinguished citizens of New Granada were killed at the hands of the Spanish, and in February 1814, several Spanish prisoners were executed in Caracas and La Guaira on Bolívar's orders.

"Spaniards and Canary Islanders, count on death, even if you are indifferent, if you do not actively work for the freedom of America. Americans, count on life, even if you are guilty."

— Decree of War to the Death. June 15th, 1813

The Declaration lasted until November 26, 1820, when the Spanish general Pablo Morillo met with Bolivar to declare the war of independence as a conventional war. The independence of Venezuela was the juridical-political process with the purpose of breaking the ties that existed between the Captaincy General of Venezuela and the Spanish Empire. It also implied the replacement of the absolute monarchy by the republic as the form of government in Venezuela.

Battle of Araure

After the end of the Admirable Campaign, the republicans were campaigning against the royalists in central western Venezuela. In one of those battles, near Barquisimeto, the republicans faced the royalists led by José Ceballos on November 10. The republicans were defeated due to the lack of coordination among the army. Deeply annoyed, the Libertador ordered to merge the remains of the battalions "Aragua", "Caracas" and "Agricultores" that had participated in the battle, into a single battalion that would not be named.

Venezuela was under the control of the patriots in the middle of 1813, except for the provinces of Guayana and Maracaibo. In September 1813 the royalists received reinforcements from Cádiz extending to armed confrontations throughout the country, while the successes of the patriots continued until the end of 1813. In these encounters the Battle of Araure stands out, in which Simón Bolívar defeated José Ceballos.

On December 3, 1813, Simón Bolívar learned that the royalist forces (3500 men), under the command of Brigadier José Ceballos, had met with those of José Yáñez in the village of Araure in the State of Portuguesa; and by virtue of this, he ordered all the forces that were in El Altar and Cojedes to concur to the concentration that would take place in the town of Aguablanca. On 5 December, the Republicans marched towards Araure and camped about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) from the town, in front of the royalists, who had deployed at the entrance of the mountain of the Acarigua river; with their wings supported by woods and their front covered by a small lake, their back was protected by a forest, they also had 10 pieces of artillery.

Colonel Florencio Jiménez, commander of the Caracas, was designated as the commander of the Batallón sin nombre ("Battalion without a name.") To further humiliation, the battalion received spears instead of rifles as combat weapons. The battalion became the mockery of the republican army, until it received its chance to prove its worth again on 5 December 1813 in Araure. In the battle of Araure, the action of the nameless battalion was decisive. Armed only with spears they attacked the battalion Numancia—one of the best Spanish battalions—and managed to disorganize their cadres, forcing them to retreat.[13]

On 5 December, the Republicans pawned the action and were immediately flanked and cut off by a cavalry column; the small attacking force was virtually destroyed. Meanwhile, Bolivar deployed his divisions in battle to resume the attack. Colonel Manuel Villapol was placed on the right; Colonel Florencio Palacios in the center and Lieutenant Colonel Vicente Campo Elías, with the Barlovento battalion, on the left. The cavalry covered the 2 flanks of the device. A cavalry corps was assigned as a reserve. Before the Republican attack, Ceballos marched his cavalry against the right of the attackers, to distract and disorganize them, but Bolivar, attentive to this movement, engaged his reserve, which disorganized and put the opposing cavalry in flight.

This intervention of Bolivar allowed the break of the enemy front, action that produced great confusion inside the defensive position, with the consequent triumph of the republicans. A division was in charge of going through the battlefield, which was covered with corpses and supplies of all kinds, while Bolivar himself was in charge of the pursuit of the defeated. The Republican forces marched that day to Aparición de la Corteza, where Bolívar fixed his provisional headquarters. The Battle began at dawn and lasted approximately six hours. The royalist troops were numerically superior to the patriot troops. The patriots held 200 prisoners, four flags and numerous pieces of artillery. In this single clash, passionate and violent, more than 500 horsemen of Yáñez, the Ñaña of the llaneros, were killed. Here fought the battalion that in the past day of Barquisimeto was punished by the Libertador, denying him the name and the right to carry the flag. But so bravely behaved in action, that Bolivar told the soldiers the next day:

"Your courage has won yesterday on the battlefield, a name for your corps, and even in the midst of the fire, when I saw you triumphant, I proclaimed it of the Victor Battalion of Araure. You have taken from the enemy flags that at one time were victorious; the famous invincible call of Numancia has been won."[14]

Fall of the Second Republic

The Battle of Úrica was a tactical military action of the Venezuelan War of Independence fought in the town of Úrica in the current state of Anzoátegui on December 5, 1814, between the Venezuelan field marshal José Félix Ribas and José Tomás Boves who was recognized for his extreme cruelty, both on and off the battlefield. Rafael María Baralt describes him as cruel and bloodthirsty for the application of the law of talion with which he responded to Bolívar's actions. Boves commanded the royalists in the Battle of Úrica that had as outcome, the death of the fearsome commander. Ribas had 2,000 men for this enterprise, led by José Tadeo Monagas, Pedro Zaraza, Manuel Cedeño, Francisco Parejo and others.

Upon arriving at the site of El Areo, Ribas proceeded to the formation of 2 cavalry columns of 180 men, which received the names of Rompelíneas, with Monagas and Zaraza as commanders. After making all the preparations for the battle, the patriot detachment marched during the night of December 4 to 5, to dawn in Úrica in front of the royalists—Boves had already joined the place—deployed in 3 columns in a great savannah. The hostilities were initiated by Boves, when he went out with his column to confront the one commanded by Colonel Bermudez, who was able to reject the attack.

This initial success of the patriots allowed Ribas to place his men in line of battle and with them he charged against the royalists, who responded with intense artillery fire. At this moment, Ribas ordered the Rompelíneas columns to attack the enemy right column, which was successfully executed. When Boves realized that his column had been enveloped, he left his center precipitously and perished in the clash. The rest of the royalist forces—center and left—charged against the republican line and enveloped it, and thus obtained the victory, the casualties were numerous in both sides.

Remove ads

Third Republic

Summarize

Perspective

The third republic corresponds to the period between 1817 and December 1819, the year in which Simón Bolívar created the Gran Colombia republic. After the fall of the Second Republic, the patriot leaders took refuge in the islands of the Caribbean Sea, especially in Jamaica, Trinidad, Haiti and Curacao. From there, and with the support of those countries, especially Haiti, they resumed the struggle.

Bolivar returns to New Granada, to try to repeat the feat of the Admirable Campaign, an action that is rejected by his supporters. Feeling misunderstood in Cartagena de Indias, he decides to take the road of exile to Jamaica on May 9, 1815, encouraged by the idea of reaching the English-speaking world and convincing it of his cooperation with the ideal of Spanish-American independence. He lived in Kingston from May to December 1815, a time he dedicated to meditation and reflection on the future of the American continent in view of the situation regarding the destiny of Mexico, Central America, New Granada—including present-day Panama—Venezuela, Buenos Aires, Chile and Peru. The Letter from Jamaica is a text written by Simón Bolívar on September 6, 1815, in Kingston, in response to a letter from Henry Cullen in which he explains the reasons that caused the fall of the Second Republic in the context of the Venezuelan Independence. Although the Letter was originally addressed to Henry Cullen, it is clear that its fundamental objective was to call the attention of the most powerful liberal nation of the 19th century, Great Britain, so that it would decide to get involved in the American independence.

The Margarita situation

Around the year of 1815, General Juan Bautista Arismendi is provisional Governor of isla de Margarita. The Spanish harassment began throughout the territory of the republic, for some months he and his family live in the outskirts of La Asunción under the espionage and the pressure that the Spanish authorities maintained on the sympathizers of the patriot cause in the island. In September 1815, Arismendi is ordered to be arrested, he escapes and hides with one of his sons in the Montañas de Copey. On September 24, his wife Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi, who was pregnant, is taken hostage to subdue her husband and locked up under surveillance in the house of the Arnés family, days later she is transferred to a dungeon of the Castillo Santa Rosa in La Asunción.

It is in this dark and unlit dungeon of the fortress that Luisa's torture begins due to the mistreatment and humiliations committed by the Spanish troops, to which she never yielded. A sentry watches even her slightest movements, and she is forced to eat the ranch that they give her as her only food. Luisa remains seated night and day without moving so as not to attract the attention of the guard. One day the chaplain of the fortress, returning from his duties, passes by her door and stares at that woman in an attitude of defeat, of humiliation. Moved to compassion for her condition, he manages to get food from his own house, to suppress the sentry and to place a light to illuminate the dungeon during the night.

The military actions of General Arismendi allow him to make prisoners to several Spanish chiefs, among them commander Cobián of the fortress of Santa Rosa, for which the royalist chief Joaquín Urreiztieta proposes Arismendi to exchange those prisoners for his wife. Such an offer is not accepted and the emissary receives as an answer: "Tell the Spanish chief that without a country I don't want a wife." From that moment on, the conditions of captivity worsen and the possibility of freedom vanishes when the patriots fail in an attempt to assault the fortress. A month after her imprisonment, one night she hears a loud alarm and realizes that an assault on the barracks is being prepared. She gets hope for a triumph of her own, but at dawn, when all is calm, she hears only the wailing of the dying and wounded from the fray.

Hours later the soldiers took her out of her prison to walk her on the esplanade of the barracks, where the prisoners had been shot. Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi trembles at the idea that she is also going to be sacrificed, but she was wrong: the purpose of her executioners was for her to walk over the corpses of the shot patriots, to walk over those lifeless bodies that had had the audacity to want to free her. The spilled blood flows into the prison cistern and Luisa is forced to quench her thirst with that putrid and pestilent water mixed with the blood of her own kin. On January 26, 1816, Luisa gave birth to a baby girl who died at birth due to the conditions of childbirth in the dungeon where she was imprisoned.

During all this time she was kept incommunicado and without news of her relatives. The triumphs of the republican forces commanded by Arismendi in Margarita and by General José Antonio Páez in Apure determined that Brigadier Moxó ordered the transfer of Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi to Cadiz, for this reason she was taken again to the prison of La Guaira on November 24, 1816, and embarked on December 3. On the high seas, they are attacked by a corsair ship that seizes all the cargo and the passengers are abandoned on the island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Unable to return to Venezuela, Luisa arrives in Cadiz. She is presented before the captain general of Andalusia, who protests against the arbitrary decision of the Spanish authorities in America and gives her the category of confined, after she pays a bond and commits herself to appear monthly before the judge. During her stay in Cadiz, she refused to sign a document in which she declared her loyalty to the King of Spain and denied her husband's patriotic affiliation, to which she responded that her husband's duty was to serve his country and fight to liberate it. The exile passed without news of her mother and her husband.

When the heroine Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi was taken prisoner and the royalist chief demanded the surrender of her husband who said, "Without a country I don't want a wife," she answered, "Let my husband fulfill his duty and I will know how to fulfill mine."[15]

Expedition of Los Cayos

The expedition of Los Cayos de San Luis or simply Expedition of Los Cayos is the name given to the two invasions that the Libertador Simón Bolívar carried out from Haiti at the end of 1815 during 1816 with the purpose of liberating Venezuela from the Spanish forces. After leaving the port of Los Cayos, in the western part of Haiti, it stopped for 3 days at Beata Island south of the border between Haiti and Santo Domingo, to continue its itinerary in which the first days of April 1816 were off the southern coast of what is today the Dominican Republic; on April 19, 1816, they arrived at isla de Vieques near the coast of Puerto Rico, an event that was celebrated with artillery salvos; On April 25, they arrive at the Dutch island of Saba, 20 km (12 mi) from San Bartolomé, from where they head towards Margarita, fighting on 2 May before arriving there, the naval battle of Los Frailes in which the squadron of Luis Brión is victorious and captures the Spanish brigantine El Intrépido and the schooner Rita. On 3 May 1816, they touch Venezuelan soil on the island of Margarita, where on the 6 May, an assembly headed by General Juan Bautista Arismendi ratifies the special powers conferred to Bolívar in Los Cayos.

After this ratification, Bolívar's expeditionary forces pass to Carúpano where they finally disembark and proclaim the abolition of slavery and then continue to Ocumare de la Costa where they disembark and reach Maracay but must retreat, harassed by Morales leaving part of the park on the beach and half of his soldiers who under McGregor undertake the retreat by land through the Valles de Aragua del Este, known as the Retirada de los Seiscientos ("Retreat of the Six Hundred"). After returning to Haiti and organizing a new expedition, Bolívar set sail from the port of Jacmel and arrived at Juan Griego on December 28, 1816, and at Barcelona on the 31st where he established his headquarters and planned a campaign on Caracas with the concentration of the forces operating in Apure, Guayana and Oriente but after a series of inconveniences he abandoned the plan and moved to Guayana to take command of the operations against the royalists in the region.

In spite of the setbacks suffered by the expeditionaries and by the Libertador himself in Ocumare, the historical importance of the Expedition of Los Callos lies in the fact that it allowed Santiago Mariño, Manuel Piar and later José Francisco Bermúdez to undertake the liberation of the eastern part of the country, and MacGregor with Carlos Soublette and other leaders to definitively enter Tierra Firme, to open the way to the definitive triumph of the Republic.

Disembarking on the Coasts

The Retreat of the Six Hundred was a journey of hundreds of kilometers through territory hostile to the patriots that occurred during the Expedition of Los Cayos in 1816, fighting along the way with few weapons and ammunition. Once the retreat was over, the six hundred rejoined the eastern patriot forces under the command of Manuel Piar with renewed confidence.

The Venezuelan patriots had disembarked on the coast of Aragua and from there they divided into several columns penetrating through the jungle and reaching Maracay, but the offensive launched by Francisco Tomás Morales in response to the disembarkation pushed them back to the beaches. In the disorder that followed, the patriots embarked hastily, leaving on the beach most of the park they had, as well as 600 men under the command of Gregor MacGregor. Subsequently, General Santiago Mariño, seconded by José Francisco Bermúdez, marched on Irapa where he attacked and destroyed the garrison of Yaguaraparo. After the offensive he reached Carúpano, after the royalists had abandoned the square, on September 15 he established himself in Cariaco and from there, with the support of Juan Bautista Arismendi's squadron, he opened operations against the city of Cumaná, first-born of the American Continent.

After some successes in Maturín and in knowledge of the advance of Santiago Mariño on Cumaná and the retreat of Gregor MacGregor, General Piar arrived at Chivacoa with 700 men and from there passed to Ortiz to threaten Cumaná and serve as liaison to Mariño and MacGregor.

After several confrontations, Piar passed to the province of Guayana, where general Manuel Cedeño operated and united his forces, they advanced against the city of Angostura whose defense was held by brigadier Miguel de la Torre. Jacmel's expedition disembarked in Barcelona on December 31, 1816. Bolívar established his headquarters in the city and from there planned an offensive on Caracas that would be executed after a concentration of troops coming from the regions occupied by the patriots: Apure, Guayana and Cumaná. Bolívar executed a "diversion" along the coast of Píritu with the purpose of diverting the attention of the royalists towards Caracas while the planned concentration was being developed, but the defeat suffered in Clarines on January 9, 1817, leaves this diversion without effect, for which Bolívar returns to Barcelona. The political and strategic difficulties force Bolívar to suspend the "Barcelona Campaign", from there he leaves for Guayana where Manuel Piar was, leaving the forces of Barcelona under the command of general Pedro María Freites.

Guayana Campaign

The Guayana Campaign of 1816 -1817, was the second campaign carried out by the Venezuelan patriots in the Venezuelan War of Independence in the Guayana region after the 1811 -1812 campaign—which had ended in disaster.

The campaign was a great success for the republicans under the command of Manuel Piar with which they managed after several battles to expel all the royalists from the region with which they were left in power of a region rich in natural resources and communication facilities that served as a base to launch campaigns to other regions of the country.[16]

Los Llanos

With José Antonio Páez and in Guayana with Manuel Piar. San Félix and Angostura are liberated in 1818, giving the patriots a territory full of riches and with access to the sea through the Orinoco river. José Antonio Páez meets with Simón Bolívar, who came from Angostura to the south of the Orinoco to join the army of Apure in the campaign against Guárico.

General Páez recognized Bolívar's authority and on February 12, 1818, with the Toma de las Flecheras where the llanero lancers crossed the Apure River and jumped into the river on their horses swimming before the confused sight of the royalists and took the Spanish boats. Then in the Battle of Calabozo, Bolívar is victorious over Pablo Morillo, Paez takes charge as commander of the vanguard to pursue the Spaniards and defeats them in the Uriosa on February 15, 1818.

The Battle of Las Queseras del Medio was an important military action carried out on April 2,[note 1] falling on his pursuers and destroying the royalist cavalry fleeing back to their camp. Las Queseras was the greatest triumph of General Páez's military career, in recognition of the brilliant action, Bolívar decorates him with the Order of the Liberator the following day.

After Páez is promoted in San Juan de Payara by the Libertador to major general, he fought the Apure campaign together with Bolívar against Morillo's troops that had invaded Apure. Once the Apure campaign ended with Morillo's retreat to Calabozo, Bolívar began the Campaign for the Liberation of New Granada and Páez was assigned the functions of security and strategic reserve, to watch Morillo's movements and to cut off a possible attack by Morillo on Bolívar's forces in conjunction with the army of the east.

Congress of Angostura

On February 15, 1819, Bolívar installed the Congress of Angostura and pronounced the Discurso de Angostura which was elaborated in the context of the wars of Independence of Venezuela and Colombia.[17] The Congress brought together representatives from Venezuela, New Granada (now Colombia) and Quito (now Ecuador). The decisions initially taken were the following:

- New Granada was renamed Cundinamarca and its capital, Santa Fe renamed Bogotá. The Capital of Quito would be Quito. The Capital of Venezuela would be Caracas. The Capital of Gran Colombia would be Bogotá.

- The "Republic of Colombia" is created, which would be governed by a president. There would be a vice-president who would replace the president in his absence. (Historically, it is customary to call the Colombia of the Congress of Angostura Gran Colombia).

- The governors of the three Departments would also be called vice-presidents.

- The president and vice-president would be elected by indirect vote, but for purposes of beginning, the congress elected them as follows: President of the Republic: Simón Bolívar and Vice President: Francisco de Paula Santander. In August, Bolívar retook his task of Libertador and left for Ecuador and Peru, leaving Santander in charge of the presidency.

- Bolívar is given the title of "Libertador" and his portrait will be exhibited in the congressional session hall with the motto "Bolívar, Libertador of the Great Colombia and father of the Homeland".

On December 17, 1819, the union of Venezuela and New Granada was declared and the República de Colombia was born. Currently known as Gran Colombia. Thus culminates the Third Republic.[18]

By then, the Spanish were left with only the northern center of the country, including Caracas, Coro, Mérida, Cumaná, Barcelona and Maracaibo.

Armistice of Santa Ana

After six years of war, the Spanish general Pablo Morillo agreed to meet with Bolivar in 1820. After New Granada was liberated and the Republic of Colombia was created, Bolívar signs with the Spanish general Pablo Morillo, on 26 November 1820, an Armistice,[19] as well as a Treaty of Regularization of the War. Marshal Sucre drafted this Armistice and War Regularization Treaty, considered by Bolívar as "the most beautiful monument of piety applied to war". Captain General Pablo Morillo receives instructions from Spain on June 6, 1820, to arbitrate with Simón Bolívar a cessation of hostilities. Morillo informs Bolivar about the unilateral ceasefire of the Spanish army and the invitation to confer an agreement to regularize the war. The plenipotentiaries of both sides meet and on November 25, Bolivar and Morillo do the same. On the same 25th, the Armistice between the Republic of Colombia and Spain was signed, which suspended all military operations in sea and land in Venezuela and confined the armies of both sides to the positions they held on the day of the signing, according to the demarcation line between both.

The importance of the documents drafted by Antonio José de Sucre, in what meant his first diplomatic action, was the temporary paralyzation of the fights between the patriots and the royalists, and the end of the War to the Death initiated in 1813. The Armistice of Santa Ana allowed Bolivar to gain time to prepare the strategy for the Battle of Carabobo, which secured Venezuelan independence. The document marked a milestone in international law,[20] because Sucre set the worldwide humanitarian treatment that since then the defeated began to receive from the victors in a war. In this way he became a pioneer of human rights. The projection of the treaty was of such magnitude that Bolívar wrote in one of his letters: "(...) this treaty is worthy of Sucre's soul (...)"

The purpose of the Armistice Treaty was to suspend hostilities in order to facilitate talks between the two sides, with a view to conclude a definitive peace. This Treaty was signed for six months and obliged both armies to remain in the positions they occupied at the time of its signing.[20] The Treaty of Armistice was:

"Whereby war shall henceforth be waged between Spain and Colombia as it is waged by civilized peoples."

Pablo Morillo tells in his memoirs that when he arrived in Spain, after the embrace with Simón Bolívar and the signing of the Armistice Treaty of Santa Ana, the King of Spain called him to his presence and said:

"Explain to me how it is that you, who triumphed against the French, against the troops of Napoleon Bonaparte, arrive here defeated by savages."[21]

To which the General replied:

"Your Majesty, if you give me a Paez and 100,000 plainsmen from Apure whom you call Savages, I will lay the whole of Europe at your feet."[22]

Battle of Carabobo

When the armistice expired on April 28, 1821, both sides began a mobilization of their forces, the Spaniards had a deployment that favored a combat "in detail", defeating the patriot divisions one at a time. The patriots commanded by Bolivar, on the other hand, needed to concentrate their troops in order to obtain a single decisive battle.

The concentration of the independence troops took place in the city of San Carlos, where the armies of Bolivar, Paez and the division of Colonel Cruz Carrillo converged. The army of the east, led by José Francisco Bermúdez made a distraction maneuver advancing on Caracas, La Guaira and the Valles de Aragua that forced La Torre to send about 1000 men against him to recover the positions and secure his rear. The pro-independence army advanced from San Carlos to Tinaco covered by the advance of Colonel José Laurencio Silva, who took the royalist positions in Tinaquillo. On the 20th, the Colombian army crosses the Tinaco river and on the 23rd Bolívar reviews his forces in the Sabana de Taguanes. In the early hours of June 24, from the heights of Buenavista hill, Bolivar made a reconnaissance of the royalist position and concluded that it was impregnable from the front and from the south. Consequently, he ordered the divisions to modify their march on the left and go to the royalist right flank, which was uncovered; that is to say, Bolivar conceived a maneuver tending to overflow the enemy right wing, operation executed by the divisions of José Antonio Páez and Cedeño, while the Plaza division followed the road towards the center of the defensive position.

The Battle of Carabobo was a combat between the armies of the Great Colombia led by Simón Bolívar and that of the Kingdom of Spain led by marshal Miguel de la Torre and it occurred on June 24, 1821, in the Sabana de Carabobo. The battle resulted in a decisive victory for independence, which was crucial for the liberation of Caracas and the rest of the territory that still remained in the hands of the royalists, a fact that was definitely achieved in 1823 with the Naval Battle of Lake Maracaibo and the capture of Castillo San Felipe in Puerto Cabello. The triumph allowed Bolívar to start the Campaigns of the South while his subordinates finished the fight in Venezuela.

On June 29, Bolívar's troops entered Caracas. The white inhabitants had abandoned the city: the houses had been looted and in the streets there were only beggars and corpses.[23] Some 24,000 people left Venezuela for the Caribbean islands, the United States or Spain. Bolívar ordered the confiscation of all the possessions of those who had emigrated, including their crops.

Naval Battle of Maracaibo Lake

The Naval Battle of Lake Maracaibo also referred to as the Naval Battle of the Lake was a naval battle fought on July 24, 1823, in the waters of Lake Maracaibo in the current state of Zulia, Venezuela. It would definitively seal the Venezuelan independence from Spain being a decisive action in the naval campaigns of the Independence. The Spanish had managed to reconquer the provinces of Coro and Maracaibo, which gave them considerable territory in the west of the country.[24] The authorities of the Republic decreed a naval blockade of the coasts of the country, the entrance to Lake Maracaibo was forced by Admiral Padilla on May 8, 1823, and after several limited actions the decisive battle took place on July 24, 1823, resulting in a complete Colombian triumph. The defeat at Lake Maracaibo made Morales' position untenable and he capitulated on August 3.

Once the day was over, Admiral Padilla ordered the squadron to stay where it had fought. Shortly after, he went to the Ports of Altagracia to repair the damage to his ships. For his part, Commander Ángel Laborde went to the castle, then won the bar, touched at Puerto Cabello and with the apostadrome's archives headed for Cuba. The losses of the Republicans were 8 officers and 36 crew and troops killed, 14 of the former and 150 of the latter wounded and one officer wounded, while those of the royalists were greater, without counting the 69 officers and 368 soldiers and sailors who were taken prisoner.

In 2 hours of fierce combat the action was decided, which opened the way to negotiations with Captain General Francisco Tomás Morales; the following August 3, he was forced to surrender the rest of the royalist fleet, the square of Maracaibo, the San Carlos Castle, the San Felipe Castle in Puerto Cabello, as well as all the other sites occupied by the Spanish officers. On August 5, the last officer in the service of the King of Spain left Venezuelan territory: the freedom of Venezuela was decided.

Remove ads

Gran Colombia

This occurred between 1819 and 1830, in which Venezuela, New Granada and Ecuador were united as a single Republic called Gran Colombia. However, the dissolution of this republic had been germinating since the early days of its creation. Gran Colombia was created in 1819 by the fundamental law of the Congress of Angostura and organized by the Congress of Cúcuta, according to the Constitution of Cúcuta.

In 1827, the Gran Colombian union (to which Quito, today Ecuador, had adhered in 1823) entered into crisis and the efforts of Bolivar and some others to stop the disintegration were of no avail. In 1830, New Granada, Venezuela and Quito separated. On December 17 of that year, Bolivar died. In the Congress of Valencia were chosen the deputies who met in this city from May 6, 1830, to discuss the dissolution of Gran Colombia, with the separation of Venezuela.

Remove ads

Results

Summarize

Perspective

The independence of Venezuela was finally recognized by Spain on March 30, 1845, through a treaty of peace and friendship made between the governments of Queen Isabel II of Spain and Venezuelan President Carlos Soublette.

The equality of citizens before the law was established in the Federal Constitution of 1811.[25] Nobiliary titles and aforamientos were eliminated, laws that civilly degraded the pardos were repealed, and the right to property and security was also recognized.[25] These provisions have remained in the other constitutions passed over time in Venezuela. However, the inequality between social strata continued, although now based on the possession of wealth, rather than ethnicity.[26]

The Federal Constitution of 1811 ratified the prohibition, given on August 14, 1810, by the Supreme Junta of Caracas, to introduce black slaves into the country.[25] However, the figure of slavery was maintained until 1854 when President José Gregorio Monagas eliminated it.

Between 1821 and 1823, the expulsion of the Spaniards from Venezuelan territory was ordered. Those who had taken part in the independence movement and the elderly over 80 years of age were exempted.

Opinions on the character of the independence process are not unanimous. Some claim that the independence was an eminently political revolution, since many of its main promoters were from the local aristocracy, who would not be interested in radically changing the existing conditions of social inequality, so as not to jeopardize the hegemony to which they aspired.[26] Others think that the initial rejection of the independence process by a large part of the other social groups (pardos, Indians and blacks) gave it the nature of a social revolution, since these sectors wanted a transformation of the social and economic structure that would give rise to a more egalitarian society.[26]

Remove ads

Notes

- The accuracy of the date is disputed since although all reports indicate that the date of the military action was April 2, Paez himself quotes in his autobiography that it occurred on April 3, 1819, in the current state of Apure of Venezuela in which the independence hero, José Antonio Páez defeated more than 1000 cavalrymen of the Spanish forces accompanied by 153 lancers, being the most famous battle commanded by Páez and where the famous phrase was delivered: "¡Vuelvan Caras!" or "Turn back your faces!" (more probably: ¡Vuelvan carajo! ["Come back, damnit!"]) Source: "Lenguaje coloquial" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 April 2008.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads