Uri Zvi Greenberg

Israeli poet and politician (1896–1981) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Uri Zvi Greenberg (Hebrew: אוּרִי צְבִי גְּרִינְבֵּרְג; September 22, 1896 – May 8, 1981; also spelled Uri Zvi Grinberg) was an Israeli poet, journalist and politician who wrote in Yiddish and Hebrew.[1]

Uri Zvi Greenberg | |

|---|---|

אוּרִי צְבִי גְּרִינְבֵּרְג | |

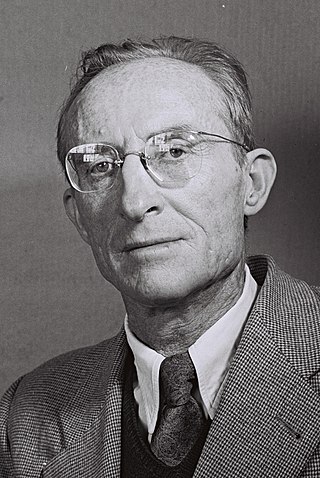

Greenberg in 1956 | |

| Faction represented in the Knesset | |

| 1949–1951 | Herut |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 September 1896 Bilyi Kamin, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 8 May 1981 (aged 84) Ramat Gan, Israel |

Widely regarded among the greatest poets in the country's history, he was awarded the Israel Prize in 1957 and the Bialik Prize in 1947, 1954 and 1977, all for his contributions to fine literature. Greenberg is considered the most significant representative of modernist Expressionism in Hebrew and Yiddish literature.

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Uri Zvi Greenberg was born in the Galician town Bilyi Kamin, in Austria-Hungary, into a prominent Hasidic family. He was raised in Lemberg (Lwów) where he received a traditional Jewish religious education.[2]

In 1915, he was drafted into the Austrian army and fought in the First World War. His experience at the fording of the Save River, where many of his comrades in arms died or were severely wounded, affected him deeply, and appeared in his future writings for years to come.[3] After returning to Lemberg, he was witness to the pogroms of November 1918.[4] Greenberg and his family miraculously escaped being shot by Polish soldiers celebrating their victory over the Ukrainians, an experience which convinced him that all Jews living in the “Kingdom of the Cross” faced physical annihilation.[3]

Greenberg moved to Warsaw in 1920, where he wrote for the radical literary publications of young Jewish poets.[5] After a brief stay in Berlin,[6] he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine (the Land of Israel) in 1923.[7]

Greenberg spent most of the 1930s in Poland, working as a Revisionist-Zionist activist, until the time when the Second World War erupted in 1939. At the outset of the war, Greenberg was able to escape and moved to Mandatory Palestine.[3] His parents and sisters remained behind and were subsequently murdered during the Holocaust.[7]

In 1950, Greenberg married Aliza, with whom he had three daughters and two sons.[1] He added "Tur-Malka" to the family name, but continued to use "Greenberg" to honor family members who were murdered in the Holocaust.[8] Greenberg was a resident of Ramat Gan.[9]

Literary career

Summarize

Perspective

Young Greenberg was encouraged to write by Shmuel Yankev Imber, a Yiddish neo-romantic poet, and Tsevi Bikeles-Shpitser, the Yiddish theater critic who edited the local newspaper Tagblat.[3] Some of his poems in Yiddish and Hebrew were published when he was 16.[10][7] His first works were published in 1912 in the Labor Zionist weekly Der yidisher arbayter (The Jewish Laborer) in Lemberg and in Hebrew in Ha-Shiloaḥ in Odessa.[5] His first book, in Yiddish, was published in Lwów while he was fighting on the Serbian front. In 1920, Greenberg moved to Warsaw, with its lively Jewish cultural scene. He was one of the founders of Di Chaliastre (literally, "the gang"), a group of young Yiddish writers that included Melech Ravitch. He also edited a Yiddish literary journal, Albatros.[11] In the wake of his iconoclastic depictions of Jesus in the second issue of Albatros, particularly his prose poem Royte epl fun veybeymer (Red Apples from the Trees of Pain). The magazine incorporated avant-garde elements both in content and typography, taking its cue from German periodicals like Die Aktion and Der Sturm.[12]

The journal was banned by the Polish censors, and in November 1922 Greenberg fled to Berlin to escape prosecution.[13] Greenberg published the last two issues of Albatros in Berlin before renouncing European society and immigrating to Palestine in December 1923.[14]

In his early days in Palestine, Greenberg wrote for Davar, one of the main newspapers of the Labour Zionist movement. His works represent a synthesis of traditional Jewish values and an individualistic lyrical approach to life and its problems; he drew on Jewish sources such as the Bible, the Talmud and the prayer book, but was also influenced by European literature.[15] In the second and third issues of Albatros, Greenberg invokes pain as a key marker of the modern era. This theme is illustrated in Royte epl fun vey beymer (Red apples from the tree of pain) and Veytikn-heym af slavisher erd (Pain-Home on Slavic Ground).[16]

In his poems and articles, he warned of the fate in store for the Jews of the Diaspora. After the Holocaust, he mourned the fact that his terrible prophecies had come true.

Political activism

Summarize

Perspective

After the 1929 Hebron massacre, he became more militant. In 1930, Greenberg joined the Revisionist camp, representing the Revisionist movement at several Zionist congresses and in Poland. With Abba Ahimeir and Yehoshua Yeivin, he founded Brit HaBirionim, a clandestine, self-declared fascist faction of the Revisionist movement which adopted an activist policy of violating British mandatory regulations. In the early 1930s, the members of Brit Habirionim group disrupted a British-sponsored census, sounded the shofar in prayer at the Western Wall despite a British prohibition, held a protest rally when a British colonial official visited Tel Aviv, and tore down Nazi flags from German offices in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.[17] When the British arrested hundreds of its members the organization effectively ceased to exist.[citation needed]

Greenberg believed that the Holocaust was a 'tragic but almost inevitable outcome of Jewish indifference to their destiny.' As early as 1923, Greenberg "envisioned and warned of the destruction of European Jewry."[18]

Scholar Dan Tamir considers Greenberg's ideology among the most prominent historical examples of "Hebrew fascism."[19]

Following Israeli independence in 1948, Greenberg joined Menachem Begin's Herut movement. In 1949, he was elected to the first Knesset. He lost his seat in the 1951 elections. After the Six-Day War he joined the Movement for Greater Israel, which advocated Israeli sovereignty over the West Bank.

Awards and recognition

- In 1947, 1954 and 1977, Greenberg was awarded the Bialik Prize for literature.[20]

- In 1957, Greenberg was awarded the Israel Prize for his contribution to literature.[21]

- In 1976, the Knesset held a special session in honor of his eightieth birthday.[22]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

In Yiddish:

- Evening Gold (פאַרנאַכטנגאָלד): collection from Grinberg’s early Neo-Romantic period.

- Mefisto (מעפיסטא): a long poem engaging with the “Faustian” world, influenced by its depictions by Oswald Spengler.

- In the Kingdom of the Cross (אין מלכות פֿון צלם): a long poem drawing on Grinberg’s experiences from the 1918 November Pogroms, intimately engaging with Christian Theology.

In Hebrew:

- A Great Terror and Moon (poetry), Hedim, 1925 (Eymah Gedolah Ve-Yareah)

- The Rising Masculinity (poetry), Sadan, 1926 (Ha-Gavrut Ha-Olah)

- A Vision of One of the Legions (poetry), Sadan, 1928 (Hazon Ehad Ha-Legionot)

- Anacreon at the Pole of Sorrow (poetry), Davar, 1928 (Anacreon Al Kotev Ha-Itzavon)

- House Dog (poetry), Hedim, 1929 (Kelev Bayit)

- A Zone of Defense and Address of the Son-of-Blood (poetry), Sadan, 1929 (Ezor Magen Ve-Ne`um Ben Ha-Dam)

- The Book of Indictment and Faith (poetry), Sadan, 1937 (Sefer Ha-Kitrug Ve-Ha-Emunah)

- From the Ruddy and the Blue (poetry), Schocken, 1950 (Min Ha-Kahlil U-Min Ha-Kahol)

- Streets of the River (poetry), Schocken, 1951 (Rehovot Ha-Nahar)

- In the Middle of the World, In the Middle of Time (poetry), Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1979 (Be-Emtza Ha-Olam, Be-Emtza Ha-Zmanim)

- Selected Poems (poetry), Schocken Books, 1979 (Mivhar Shirim)

- Complete Works of Uri Zvi Greenberg, Bialik Institute, 1991 (Col Kitvei)

- At the Hub, Bialik Institute, 2007 (Ba-'avi ha-shir)

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.