Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Tutsi

Ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Tutsi (/ˈtʊtsi/ TUUT-see[2]), also called Watusi, Watutsi or Abatutsi (Kinyarwanda pronunciation: [ɑ.βɑ.tuː.t͡si]), are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region.[3] They are a Bantu-speaking[4] ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi (the other two being the largest Bantu ethnic group Hutu and the Pygmy group of the Twa).[5]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Historically, the Tutsi were pastoralists and filled the ranks of the warriors' caste. Before 1962, they regulated and controlled Rwandan society, which was composed of Tutsi aristocracy and Hutu commoners, utilizing a clientship structure. They occupied the dominant positions in the sharply stratified society and constituted the ruling class.[5]

Remove ads

Origins and classification

Summarize

Perspective

The historian Christopher Ehret believes that the Tutsi mainly descend from speakers of an extinct branch of South Cushitic he calls "Tale south Cushitic." The Tale southern cushites entered the Great Lakes region sometime before 800BC and were pastoralists par excellence, relying only on their livestock and conceivably growing no grains themselves; they did not even practice the hunting of wild animals, and the consumption of fish was taboo, and heavily avoided. The Tale Southern Cushitic way of life shows striking similarities to the Tutsi, who heavily rely on the milk, blood, and meat of their cattle and traditionally shun the cultivation and consumption of grains, and who look down on pottery, hunting and avoid eating fish. A number of words related to pastoralism in the Rwanda-Rundi languages are Tale Southern Cushitic loanwords, such as "Bull" "cow dung" and "lion" (a livestock predator).[6][7][8][9]

This late continuation of Southern Cushites as important pastoralists in the southern half of the lacustrine region raises the intriguing possibility that the latter-day Tutsi and Hima pastoralism, most significant in the southern half of the region, is rooted in the Southern Cushitic culture and so derived from the east rather than the north.

— Christopher Ehret, UNESCO General History of Africa: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century, [10]

The Tutsi also get a significant amount of their ancestry from the Sog Eastern Sahelians (a long-extinct Nilo-Saharan group). The Sog were agro-pastoralists who entered Rwanda and Burundi in 2,000 BC, mostly settling in southern Rwanda and to the east and west of the Ruzizi River. According to Christopher Ehret They spoke a Kir-Abbaian language which was related to Nilotic and Surmic languages (but still distinct from them). The Western Lakes Bantu languages spoken by the Tutsi have many Sog Eastern Sahelian loanwords, such as the word for cow (inka), which originally meant "Cattle camp" in the Sog language, showing their contribution to Tutsi pastoralism.[11][12][13][14]

Remove ads

Central Sudanic peoples likely form another part of the ancestry of the Tutsi. Central Sudanic farmers and herders entered Rwanda and Burundi in 3,000 BC, and some of their cultural practices have stayed on after their assimilation by the Bantu. For example, in Central Sudanic-speaking societies, women are kept away from cattle. Among the Tutsi (and the neighboring Hima people to the north), women are strictly forbidden to milk cows (especially menstruating women).[15][16][17][18]

The definition of "Tutsi" has changed through time and location. Social structures were not stable throughout Rwanda, even during colonial times under the Belgian rule. Generally, the Tutsi elite or aristocracy was distinguished from Tutsi commoners.

When the Belgian colonial administration conducted censuses, it identified the people throughout Rwanda-Burundi according to a simple classification scheme. The “Tutsi" were defined as anyone owning more than ten cows (a sign of wealth) or with the physical features of a longer thin nose, high cheekbones, and being over six feet tall, all of which are common descriptions associated with the Tutsi.

In the colonial era, the Tutsi were hypothesized to have arrived in the Great Lakes region from the Horn of Africa, in accordance with the Hamitic hypothesis.[19][20]

Remove ads

Tutsi were considered by some to be of Cushitic origin, although they do not speak a Cushitic language, and have lived in the areas where they presently inhabit for at least 400 years, leading to considerable intermarriage with the Hutu in the area. Due to the history of intermingling and intermarrying of Hutu and Tutsi, some ethnographers and historians are of the view that Hutu and Tutsi cannot be called distinct ethnic groups.[21][22][23]

Genetics

Summarize

Perspective

Y-DNA (paternal lineages)

Modern-day genetic studies of the Y-chromosome generally indicate that the Tutsi, like the Hutu, are largely of Bantu extraction (60% E1b1a, 20% B, 4% E-P2(xE1b1a)).

Paternal genetic influences associated with the Horn of Africa and North Africa are few (under 3% E1b1b-M35), and are ascribed to much earlier inhabitants who were assimilated. However, the Tutsi have considerably more haplogroup B Y-DNA paternal lineages (14.9% B) than do the Hutu (4.3% B).[24]

Autosomal DNA (overall ancestry)

In general, the Tutsi appear to share a close genetic kinship with neighboring Bantu populations, particularly the Hutu. However, it is unclear whether this similarity is primarily due to extensive genetic exchanges between these communities through intermarriage or whether it ultimately stems from common origins:

Remove ads

[...] generations of gene flow obliterated whatever clear-cut physical distinctions may have once existed between these two Bantu peoples – renowned to be height, body build, and facial features. With a spectrum of physical variation in the peoples, Belgian authorities legally mandated ethnic affiliation in the 1920s, based on economic criteria. Formal and discrete social divisions were consequently imposed upon ambiguous biological distinctions. To some extent, the permeability of these categories in the intervening decades helped to reify the biological distinctions, generating a taller elite and a shorter underclass, but with little relation to the gene pools that had existed a few centuries ago. The social categories are thus real, but there is little if any detectable genetic differentiation between Hutu and Tutsi.[25]

Height

Remove ads

Their average height is 5 feet 9 inches (175 cm), although individuals have been recorded as being taller than 7 feet (210 cm).[26][27][28]

History

Summarize

Perspective

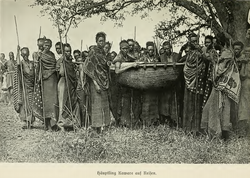

The traditional Tutsi king's palace in Nyanza (top) and Rwanda c. 1900, Tutsi Chief Kaware travelling (bottom)

Prior to the arrival of colonists, Rwanda had been ruled by a Tutsi-dominated monarchy since the 15th century.[29][30] In 1897, Germany established a presence in Rwanda with the formation of an alliance with the king, beginning the colonial era.[31] Later, Belgium took control in 1916 during World War I. Both European nations ruled through the Rwandan king and perpetuated a pro-Tutsi policy.

In Burundi, meanwhile, a ruling faction known as the ganwa emerged and quickly assumed effective control of the country's administration. The ganwa who relied on support from both Hutu and Tutsi populations to rule, were perceived within Burundi as neither Hutu nor Tutsi.[32][33]

Rwanda was ruled as a colony by Germany (from 1897 to 1916) and by Belgium (from 1922 to 1961). Both the Tutsi and Hutu had been the traditional governing elite, but both colonial powers allowed only the Tutsi to be educated and to participate in the colonial government. Such discriminatory policies engendered resentment.[citation needed]

When the Belgians took over, they believed the areas,which were formerly under German colonial control, could be better governed if they continued to identify the different populations as they had been previously identified. In the 1920s, the Belgian authorities required the population to identify with a particular ethnic group and the authorities classified them accordingly in censuses.[34][35]

In 1959, Belgium reversed its stance and allowed the majority Hutu to assume control of the government through universal elections after independence. This partly reflected internal Belgian domestic politics, in which the discrimination against the Hutu majority came to be regarded as similar to oppression within Belgium stemming from the Flemish-Walloon conflict, and the democratization and empowerment of the Hutu was seen as a just response to the Tutsi domination. Belgian policies wavered and flip-flopped considerably during this period leading up to independence of Burundi and Rwanda.[citation needed]

Independence of Rwanda and Burundi (1962)

The Hutu majority in Rwanda had revolted against the Tutsi and was able to take power. Tutsi fled and created exile communities outside Rwanda in Uganda and Tanzania.[36][37][38][39][40] Overt discrimination from the colonial period was continued by different Rwandan and Burundian governments, including identity cards that distinguished Tutsi and Hutu.

Burundian genocide (1993)

In 1993, Burundi's first democratically elected president, Melchior Ndadaye, a Hutu, was assassinated by Tutsi officers, as was the person entitled to succeed him under the constitution.[41] This sparked a genocide in Burundi between Hutu political structures and the Tutsi, in which "possibly as many as 25,000 Tutsi" – including military, civil servants and civilians[42] – were murdered by the former and "at least as many" Hutu were killed by the latter.[43][44] Since the 2000 Arusha Peace Process, today in Burundi the Tutsi minority shares power in a more or less equitable manner with the Hutu majority. Traditionally, the Tutsi had held more economic power and controlled the military.[45]

1994 genocide against the Tutsi

A similar pattern of events took place in Rwanda, but there the Hutu came to power in 1962. They in turn often oppressed the Tutsi, who fled the country. After the anti-Tutsi violence around 1959–1961, Tutsi fled in large numbers.

These exile Tutsi communities gave rise to Tutsi rebel movements. The Rwandan Patriotic Front, mostly made up of exiled Tutsi living primarily in Uganda, attacked Rwanda in 1990 with the intention of taking back the power. The RPF had experience in organized irregular warfare from the Ugandan Bush War, and got much support from the government of Uganda. The initial RPF advance was halted by the lift of French arms to the Rwandan government. Attempts at peace culminated in the Arusha Accords.

The agreement broke down after the assassination of the Rwandan and Burundian presidents, triggering a resumption of hostilities and the start of the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, in which the Hutu then in power killed an estimated 500,000–600,000 people, largely of Tutsi origin.[46][47][48][49][50][51] Victorious in the aftermath of the genocide, the Tutsi-ruled RPF came to power in July 1994.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

In the Rwanda territory, from the 15th century until 1961, the Tutsi were ruled by a king (the mwami). Belgium abolished the monarchy, following the national referendum that led to independence. By contrast, in the northwestern part of the country (predominantly Hutu), large regional landholders shared power, similar to Buganda society (in what is now Uganda).

Under their holy king, Tutsi culture traditionally revolved around administering justice and government. They were the only proprietors of cattle, and sustained themselves on their own products. Additionally, their lifestyle afforded them a lot of leisure time, which they spent cultivating the high arts of poetry, weaving and music. Due to the Tutsi's status as a dominant minority vis-a-vis the Hutu farmers and the other local inhabitants, this relationship has been likened to that between lords and serfs in feudal Europe.[52]

According to Fage (2013), the Tutsi are serologically related to Bantu and Nilotic populations. This in turn rules out a possible Cushitic origin for the founding Tutsi-Hima ruling class in the lacustrine kingdoms. However, the royal burial customs of the latter kingdoms are quite similar to those practiced by the former Cushitic Sidama states in the southern Gibe region of Ethiopia. By contrast, Bantu populations to the north of the Tutsi-Hima in the mount Kenya area such as the Agikuyu were until modern times essentially without a king (instead having a stateless age set system which they adopted from Cushitic peoples) while there were a number of Bantu kingdoms to the south of the Tutsi-Hima in Tanzania, all of which shared the Tutsi-Hima's chieftaincy pattern. Since the Cushitic Sidama kingdoms interacted with Nilotic groups, Fage thus proposes that the Tutsi may have descended from one such migrating Nilotic population. The Nilotic ancestors of the Tutsi would thereby in earlier times have served as cultural intermediaries, adopting some monarchical traditions from adjacent Cushitic kingdoms and subsequently taking those borrowed customs south with them when they first settled amongst Bantu autochthones in the Great Lakes area.[52] However, little difference can be ascertained between the cultures today of the Tutsi and Hutu; both groups speak the same Bantu language.[53] The rate of intermarriage between the two groups was traditionally very high, and relations were amicable until the 20th century. Many scholars have concluded that the determination of Tutsi was and is mainly an expression of class or caste, rather than ethnicity. Rwandans have their own language, Kinyarwanda. English, French and Swahili serve as additional official languages for different historic reasons, and are widely spoken by Rwandans as a second language.[54]

Tutsi in the Congo

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

Scholars have long recognized[citation needed] that the Tutsi presence in the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is best understood by distinguishing between two principal groups, whose histories have been significantly shaped—and often distorted—by colonial policies and later political struggles.

The Banyamulenge

The Banyamulenge are a Tutsi group that primarily resides in parts of South Kivu, specifically in the Uvira region of the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). They trace their origins mainly to Rwandan laborers and refugees who began migrating into the region during the colonial period, starting as early as 1916. This migration was a direct result of World War I, when Rwandans were brought into the area to work in the mines, agricultural fields, and other labor-intensive sectors. The Banyamulenge do not have indigenous Congolese roots, but instead, their presence in the region is the result of external migration and colonial labor practices.

The Mulenge region, which the Banyamulenge inhabit, was originally home to the Bafulero (Bafuliru) people, who were the first inhabitants of the area.[citation needed] Mulenge, a mountain and region located in Uvira, South Kivu, was named by the Bafulero people, long before the arrival of the Tutsi groups. The term "Mulenge" referred to their mountain, their region, and their cultural heritage. However, when Rwandan Tutsi groups, including the Banyamulenge, began to settle in the area, they began to adopt and later popularize the name for their own identification with the land. This adoption of the name was partly to help them define a territory that, originally, was not theirs. It was a way of self-identification in a place that was still home to the Bafulero, and later to many other ethnic groups.

Historical research and scholarly work[citation needed] show that the Banyamulenge are the descendants of Rwandan Tutsi refugees and migrants who arrived in the DRC after the Berlin Conference (1884–1885), which reshaped borders in Central Africa. While the Tutsi people have a long history in Rwanda, their arrival in the Congo occurred after the colonial period, not before. This significant point highlights that the Banyamulenge, while culturally related to Rwandan Tutsi, are not indigenous to Congo, as they began to migrate during the colonial era, in a time when the borders of modern African states were already being drawn and redefined. Their presence in the DRC was the result of migration rather than indigenous settlement, and their claim to the land must be understood in this context.

Remove ads

The Rwandan Tutsi immigrants initially began settling in the eastern DRC in the early 20th century,[citation needed] bringing with them cultural and social practices from Rwanda. However, they were not necessarily accepted by the indigenous Congolese communities. Their presence, however, was consolidated as the Rwandan refugee crisis evolved in the region, especially after the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, when large numbers of refugees fled to Congo. The Banyamulenge, as part of the Tutsi population, increasingly became a key player in the evolving ethnic and political dynamics of the region.

Although the Banyamulenge have sought to define themselves as a distinct group with ties to both the Tutsi ethnic identity and the land of South Kivu, their efforts have been met with significant tension from other Congolese groups who view their claims to land and political power with skepticism.[citation needed] Many view the Banyamulenge as foreigners rather than part of the indigenous population of the DRC. This conflict over identity and land ownership has led to persistent tension and violence in the region, contributing to the instability in the Kivu provinces and further complicated by regional politics, particularly the involvement of Rwanda in the ongoing conflict.

In summary, the Banyamulenge's origins are deeply tied to Rwandan migration into Congo during the colonial period. They are the descendants of Rwandan laborers and refugees who were brought into the region after World War I, and their presence in the region has caused significant conflict over territoriality and identity.[citation needed] The Bafulero people, the original inhabitants of Mulenge, have consistently disputed the claim that the Banyamulenge are entitled to the land. The historical context of the Banyamulenge’s presence in the DRC highlights the complexity of the conflict and the ongoing struggles over land, power, and identity that continue to shape the region today.[citation needed]

Banyarwanda in North Kivu and South Kivu

A second Tutsi presence is found among the broader Banyarwanda community in parts of North Kivu and the Kalehe region of South Kivu. This community, which includes both Tutsi and Hutu, is largely the result of multiple migratory waves from neighboring Rwanda, occurring over the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-genocide periods. In particular, the mass exodus during and after the Rwandan Genocide of 1994 is well documented and has significantly reshaped the ethnic landscape in eastern Congo.[55][56] The academic consensus holds that these migratory processes, far from being a single exogenous event, have complex historical antecedents that continue to influence regional politics.

Conflict and Contemporary Issues

Remove ads

The eastern DRC has been a hotspot of conflict for decades, involving numerous armed groups. Some of these, notably those evolving from the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) into what became known as the M23, have been led by individuals of Tutsi background. However, the portrayal of these groups solely through an ethnic lens oversimplifies the situation. Academic studies agree that the roots of the conflict lie in a mixture of colonial legacies, competition over valuable resources such as cobalt, and deep-seated political and social grievances.[57] Reports from international organizations have documented serious human rights abuses—including the recruitment of child soldiers and illegal exploitation of mineral wealth—but these are best understood within the broader framework of state fragility and international economic pressures rather than as a straightforward ethnic conflict.[58]

Notable people

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads