Treaty of Alcáçovas

1479 treaty between Spain and Portugal From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

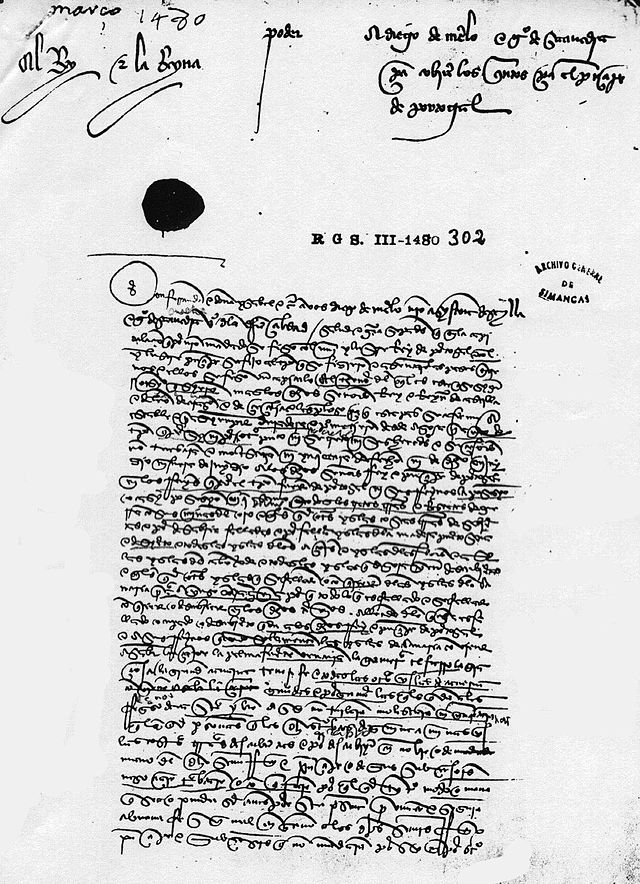

The Treaty of Alcáçovas (also known as Treaty or Peace of Alcáçovas-Toledo) was signed on 4 September 1479 between the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon on one side and Afonso V and his son, Prince John of Portugal, on the other side. It put an end to the War of the Castilian Succession, which ended with a victory of the Castilians on land[1] and a Portuguese victory on the sea.[2] [1] The four peace treaties signed at Alcáçovas reflected that outcome: Isabella was recognized as Queen of Castile while Portugal reached hegemony in the Atlantic Ocean.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

The treaty intended to regulate:

- The renunciation of Afonso V and Castilian Monarchs to the Castilian throne and Portuguese throne, respectively

- The division of the Atlantic Ocean and overseas territories into two zones of influence

- The destiny of Juana de Trastámara

- The contract of marriage between Isabella, the eldest daughter of the Catholic Monarchs, with Afonso, heir of Prince John. This was known as Tercerias de Moura, and included the payment to Portugal of a war compensation by the Catholic Monarchs in the form of marriage dowry.[3]

- The pardon of the Castilian supporters of Juana

War of the Castilian Succession

Summarize

Perspective

After the death of Henry IV in 1474, the Castilian crown was disputed between the half-sister of the king, Isabella I of Castile, married to Prince Ferdinand II of Aragon, and the king's daughter, Juana de Trastámara, popularly known as la Beltraneja – because her father was alleged to be Beltrán de la Cueva. In the subsequent civil war, Afonso V of Portugal married Juana and invaded Castile (May 1475), defending her rights.[4]

Parallel to the dynastic struggle, there was a fierce naval war between the fleets of Portugal and Castile to access and control overseas territories − especially Guinea – whose gold and slaves were the heart of the Portuguese power. The main events of this war were the indecisive[5][6] battle of Toro (1 March 1476), transformed[7] in a strategic victory by the Catholic Monarchs and the battle of Guinea[8] (1478), which granted Portugal the hegemony in the Atlantic Ocean and disputed territories.

Historian Stephen R. Bown wrote:[9]

When Ferdinand and Isabella secured their rule after the Battle of Toro on 1 March 1476- effectively eliminating the threat of Portuguese invasion but not officially ending the war- they renewed the twenty-year-old Castilian claim to their "ancient and exclusive" rights to the Canary Islands and the Guinea coast .... They encouraged Spanish merchant ships to take advantage of the political disruption and considered making direct attacks on Portuguese vessels returning from Guinea, with the objective of seizing the monopoly.... In 1478 a Spanish fleet of thirty-five caravels was intercepted by an armed Portuguese squadron. Most of the fleet was captured and taken to Lisbon. [I]n 1479 ... the two nations concluded terms for peace with the treaty of Alcáçovas, ending the struggle for the succession as well as their battle at sea.

Treaty outcomes

- Juana de Trastamara and Afonso V waived their rights to the Castilian throne in favour of the Catholic Monarchs, who gave up their claims over the throne of Portugal.

- There was a sharing of the Atlantic territories between both countries and a delimitation of the respective spheres of influence.

- With the exception of the Canary Islands, all territories and shores disputed between Portugal and Castile stayed under Portuguese control; Guinea with its gold mines, Madeira (discovered in 1419), the Azores (discovered about 1427) and Cape Verde (discovered about 1456). Portugal also won the exclusive right of conquering the Kingdom of Fez.

- Castile's rights over the Canary Islands were recognised while Portugal won the exclusive right of navigating, conquering and trading in all the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands. Thus, Portugal attained hegemony in the Atlantic not only for its known territories but also for those discovered in the future. Castile was restricted to the Canaries.

- Portugal gained a war compensation of 106,676 dobles of gold in the form of Isabella's dowry.[3]

- Both infants (Isabella and Afonso) stayed in Portugal under the regiment of Tercerias, at the village of Moura, waiting for the appropriate age. The Catholic Monarchs were responsible for all costs of maintaining the Tercerias.

- Juana had to choose between staying in Portugal and entering a religious order or marrying Prince Juan, son of the Catholic Monarchs: she chose the former.

- The Castilian supporters of Juana and Afonso were pardoned.

Possessions

Summarize

Perspective

This treaty, ratified later by the papal bull Aeterni regis in 1481, essentially gave the Portuguese free rein to continue their exploration along the African coast while guaranteeing Castilian sovereignty in the Canaries. It also prohibited Castilians from sailing to the Portuguese possessions without Portuguese licence. The Treaty of Alcáçovas, establishing Castilian and Portuguese spheres of control in the Atlantic, settled a period of open hostility, but it also laid the basis for future claims and conflict.

Portugal's rival Castile had been somewhat slower than its neighbour to begin exploring the Atlantic, and it was not until late in the fifteenth century that Castilian sailors began to compete with their western neighbours. The first contest was for control of the Canary Islands, which Castile won. It was not until the union of Aragon and Castile and the completion of the Reconquista that the larger country became fully committed to looking for new trade routes and colonies overseas. In 1492, the joint rulers of the country decided to fund Christopher Columbus' expedition that they hoped would bypass Portugal's lock on Africa and the Indian Ocean, and instead, reach Asia by travelling west over the Atlantic.

Precedent in international law

Summarize

Perspective

The Treaty of Alcáçovas was the first document to define "the field reserved for the future discoveries" of Spain and Portugal, specifically delineating "the respective rights of the two crowns over the territories of the African Continent and the Atlantic islands."[10] In this way, it can be considered a landmark in the history of colonialism. It is one of the first international documents formally outlining the principle that European powers are empowered to divide the rest of the world into "spheres of influence" and colonise the territories located within such spheres, and that any indigenous peoples living there need not be asked for consent. This remained a generally accepted principle in the ideology and practice of European powers up to the 20th century decolonization. The Treaty of Alcáçovas could be regarded as the ancestor of many later international treaties and instruments based on the same basic principle.[11] These include the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which further codified the positions of Spain and Portugal in world exploration,[12] and the resolutions of the 1884 Conference of Berlin, four centuries later, which in much the same way divided Africa into colonial spheres of influence.

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.