Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

Illuminated manuscript book of hours From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (French pronunciation: [tʁɛ ʁiʃz‿œʁ dy dyk də beʁi]; English: The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry[1]), or Très Riches Heures, is an illuminated manuscript that was created between c. 1412 and 1416. It is a book of hours, which is a Christian devotional book and a collection of prayers said at canonical hours. The manuscript was created for John, Duke of Berry, the brother of King Charles V of France, by Limbourg brothers Paul, Johan and Herman.[2] The book is now MS 65 in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

Consisting of a total of 206 leaves of very fine quality parchment,[2] 30 cm (12 in) in height by 21.5 cm (8+1⁄2 in) in width, the manuscript contains 66 large miniatures and 65 small. The design of the book, which is long and complex, has undergone many changes and reversals. Many artists contributed to its miniatures, calligraphy, initials, and marginal decorations, but determining their precise number and identity remains a matter of debate. Painted largely by artists from the Low Countries, often using rare and costly pigments and gold,[3] and with an unusually large number of illustrations, the book is one of the most lavish late medieval illuminated manuscripts. The work was created in the late artistic phase of the International Gothic style.

When the Limbourg brothers and their sponsor died in 1416 (possibly victims of plague) the manuscript was left unfinished. It was further added upon in the 1440s by an anonymous painter, who many art historians believe was Barthélemy d'Eyck. In 1485–1489, it was brought to its present state by the painter Jean Colombe on behalf of the Duke of Savoy. It was acquired by the Duc d'Aumale in 1856.

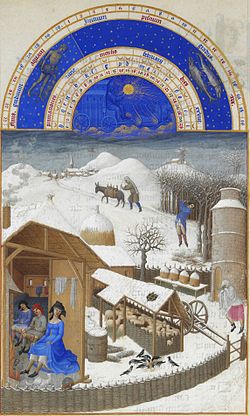

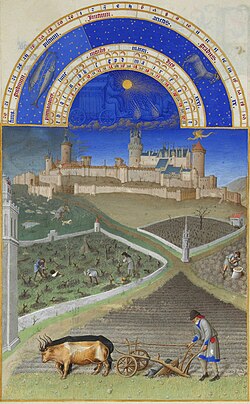

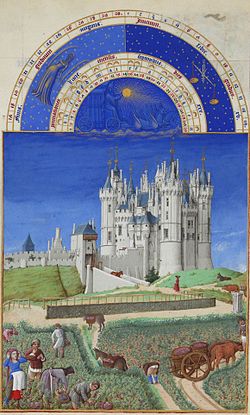

After three centuries in obscurity, the Très Riches Heures gained wide recognition in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, despite having only very limited public exposure at the Musée Condé. Its miniatures helped to shape an ideal image of the Middle Ages in the collective imagination, often being interpreted to serve political and nationalist agendas.[4] This is particularly true for the calendar images, which are the most commonly reproduced. They offer vivid representations of peasants performing agricultural work as well as aristocrats in formal attire, against a background of remarkable medieval architecture.

Historical context

Summarize

Perspective

The "Golden Age" of the book of hours in Europe took place from 1350 to 1480; the book of hours became popular in France around 1400 (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969). At this time many major French artists undertook manuscript illumination.

Duke of Berry

John, Duke of Berry, is the French prince for whom the Très Riches Heures was made. Berry was the third son of the future king of France, John the Good, and the brother and uncle of the next two kings. Little is known of Berry's education, but it is certain that he spent his adolescence among arts and literature (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). The young prince lived an extravagant life, necessitating frequent loans. He commissioned many works of art, which he amassed in his Saint Chapelle mansion. Upon Berry's death in 1416, a final inventory was done on his estate that described the incomplete and unbound gatherings of the book as the "très riches heures" ("very rich[ly decorated] hours") to distinguish it from the 15 other books of hours in Berry's collection, including the Belles Heures ("beautiful hours") and Petites Heures ("little hours") (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

Provenance

The Très Riches Heures has changed ownership many times since its creation. The gatherings were certainly in Berry's estate on his death in 1416, but after this little is clear until 1485. A good deal is known about the lengthy and messy disposal of Berry's goods to satisfy his many creditors, which was disrupted by the insanity of the king and the Burgundian and English occupation of Paris, but there are no references to the manuscript.[5] It seems to have been in Paris for much of this period, and probably earlier; some borders suggest the style of the Parisian Bedford Master's workshop, and works from the 1410s to the 1440s by the Bedford workshop — later taken over by the Dunois Master — use border designs from other pages, suggesting that the manuscript was available for copying in Paris.[5]

Duke Charles I of Savoy acquired the manuscript, probably as a gift, and commissioned Jean Colombe to complete the manuscript around 1485–1489. Sixteenth-century Flemish artists imitated the figures or entire compositions found in the calendar (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). The manuscript belonged to Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy (1480–1530), Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515 and again from 1519 to 1530.[6] She was the second wife of Charles' son in law.

After this its history is unknown until the 18th century, when it was given its present bookbinding with the arms of the Serra family of Genoa, Italy.

It was inherited from the Serras by Baron Felix de Margherita of Turin and Milan. The French Orleanist pretender, Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale, then in exile at Twickenham near London, bought it from the baron in 1856. On his return to France in 1871 Aumale placed it in his library at the Château de Chantilly, which he bequeathed to the Institut de France as the home of the Musée Condé.[7]

Recent history

When Aumale saw the manuscript in Genoa he was able to recognize it as a commission of Berry, probably because he was familiar with a set of plates of other manuscripts of Berry published in 1834, and subsidized by the government of the duke's father, King Louis Philippe I.[8] Aumale gave the German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen breakfast and a private view of the manuscript at Orleans House, just in time for a 10-page account to appear in Waagen's Galleries and Cabinets of Art in Great Britain in 1857, so beginning its rise to fame.[9] He also exhibited it in 1862 to the members of the Fine Arts Club.[10]

The connection with the "très riches heures" listed in the 1416 inventory was made by Léopold Victor Delisle of the Bibliothèque nationale de France and communicated to Aumale in 1881, before being published in 1884 in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts; it has never been seriously disputed.[11] The manuscript took pride of place in a three-part article on all of Berry's manuscripts then known, and was the only one illustrated, with four plates in heliogravure.[12] However the manuscript was called the "Grandes Heures du duc de Berry" in this, a title now given to another manuscript, based on its larger page size. The name "Heures de Chantilly" was also used in the next decades.[13]

A monograph with 65 heliogravure plates was published by Paul Durrieu in 1904, to coincide with a major exhibition of French Gothic art in Paris where it was exhibited in the form of 12 plates from the Durrieu monograph, as the terms of Aumale's bequest forbade its removal from Chantilly.[14] The work became increasingly famous, and increasingly reproduced. The first colour reproductions, using the technique of photogravure, appeared in 1940 in the French art quarterly Verve. Each issue of this lavish magazine cost three hundred francs.[15] In January 1948, the very popular American photo-magazine Life published a feature with full-page reproductions of the 12 calendar scenes, at a little larger than their actual size but at very low-quality. Catering to American sensibilities of the time, the magazine censored one of the images by retouching the genitals of the peasant in the February scene.[16] The Musée Condé decided in the 1980s, somewhat controversially, to remove the manuscript completely both from public display and scholarly access, replacing it with copies of a complete modern facsimile.[17] Michael Camille argues that this completes the logic of the reception history of a work that has almost entirely become famous through reproductions of its images, with the most famous images having been seen in the original by only a very small number of people.[4]

Artists

Summarize

Perspective

There has been much debate regarding the identity and number of artists who contributed to the Très Riches Heures.

The Limbourg brothers

In 1884, Léopold Delisle correlated the manuscript with the description of an item in an inventory drawn up after Berry's death: "several gatherings of a very rich book of hours [très riches heures], richly historiated and illuminated, that Pol [Paul] and his brothers made".[19] Delisle's resulting attribution to Paul de Limbourg and his two brothers, Jean and Herman, "has received general acceptance and also provided the manuscript with its name."[2]

The three Limbourg brothers had originally worked under the supervision of Berry's brother, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, on a Bible Moralisée and had come to work for Berry after Philip's death. By 1411, the Limbourgs were permanent members of Berry's household (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). It is also generally agreed that another of Berry's books of hours, the Belles Heures, completed between 1408 and 1409, can also be attributed to the brothers. It is thought that the Limbourg contribution to the Très Riches Heures was between about 1412 and their deaths in 1416. Documentation from 1416 was found indicating that Jean, followed by Paul and Herman, had died. Jean de Berry died later that year (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). Apart from the main campaign of illumination, the text, border decorations, and gilding were most likely executed by assistants or specialists who remain unknown.

The choice of castles in the calendar is one factor in the dating of the brothers' contribution. The Château of Bicêtre, just outside Paris, was one of Berry's grandest residences, but does not appear in the calendar. It seems likely that this was because no image had been created by October 1411, when a large mob from Paris looted it and set it on fire in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War. However the châteaux at Dourdan (April) and Étampes (July) are both shown, although Berry lost them to the Burgundians at the end of 1411, with Étampes being badly damaged in the siege.[20]

Jean Colombe

Folio 75 of the Très Riches Heures includes Duke Charles I of Savoy and his wife. The two were married in 1485 and the Duke died in 1489, implying that it was not one of the original folios. The second painter was identified by Paul Durrieu as Jean Colombe,[21] who was paid 25 gold pieces by the Duke to complete certain canonical hours (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

There were some miniatures which were incomplete and needed filling in, for example, the foreground figures and faces of the miniature illustrating the Office of the Dead, known as the Funeral of Raymond Diocrès.[22]

There are other subtle differences between the miniatures created by the Limbourgs and Colombe. Colombe chose to set large miniatures in frames of marble and gold columns. His faces are less delicate, with more pronounced features. He also used a very intense blue paint that is seen in the landscape of some miniatures. Colombe is worked in his own style without attempting to imitate that of the Limbourgs (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). In folio 75 he followed the Limbourgs by including a depiction of one of his patron's castles in the Duchy of Savoy in the landscape background.

The Intermediate Painter

The "intermediate painter", also called the Master of the Shadows, as shadows are an element of his style, is often thought to be Barthélemy van Eyck (strictly the miniaturist known as the Master of René of Anjou, who is now normally identified with the documented painter Barthélemy van Eyck)[23] who would probably have been at work in the 1440s. Other scholars put his work as early as the 1420s, though there is no documentation for this.[6] At any rate, the intermediate artist is assumed to have worked on the manuscript sometime between 1416 and 1485. Evidence from the artistic style, as well as the details of costume, suggests that the Limbourgs did not paint some of the calendar miniatures. Figures in the miniatures for January, April, May, and August are dressed in styles from 1420. The figures strolling in October are dressed in a sober fashion indicative of the mid-fifteenth century. It is known that the gatherings fell into hands of King Charles VII after Berry's death, and it is assumed that the intermediate painter is associated with his court (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

Catherine Reynolds, in an article of 2005, approached the dating of the "intermediate painter"'s work through the borrowings from it visible in the work of other Parisian illuminators, and placed it in the late 1430s or at the start of the 1440s. This is inconveniently early for what she describes as the "generally accepted" identification with Barthélemy van Eyck, and in any case she detects a number of stylistic differences between van Eyck and the "intermediate painter."[24] Jonathan Alexander sees no stylistic need to hypothesize an intermediate painter at all.[25]

Attribution of the calendar miniatures

The artists of the calendar miniatures have been identified as follows (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988):

- January: Jean

- February: Paul

- March: Paul and Colombe

- April: Jean

- May: Jean

- June: Paul, Jean, Herman, and Colombe (?)

- July: Paul

- August: Jean

- September: Paul and Colombe

- October: Paul and Colombe (?)

- November: Colombe

- December: Paul

Pognon gives the following breakdown of the main miniatures in the Calendar, using more cautious stylistic names for the artists:[26]

- January: the courtly painter

- February: the rustic painter

- March: the courtly painter (landscape) and the Master of the Shadows (figures)

- April: the courtly painter

- May: the courtly painter

- June: the rustic painter

- July: the rustic painter

- August: the courtly painter

- September: the rustic painter (landscape)? and the Master of the Shadows (figures)

- October: the Master of the Shadows

- November: Jean Colombe

- December: the Master of the Shadows

In addition Pognon identifies the "pious painter" who painted many of the religious scenes later in the book during the initial campaign. The "courtly", "rustic" and "pious" painters would probably equate to the three Limbourg brothers, or perhaps other artists in their workshop. There are alternative analyses and divisions proposed by other specialists.

Function

A breviary consists of a number of prayers and readings in a short form, generally for use by the clergy. The book of hours is a simplified form of breviary designed for use by the laity where the prayers are intended for recital at the canonical hours of the liturgical day. Canonical hours refer to the division of day and night for the purpose of prayers. The regular rhythm of reading led to the term "book of hours".(Cazelles and Rathofer 1988)

The book of hours consists of prayers and devotional exercises, freely arranged into primary, secondary and supplementary texts. Other than the calendar at the beginning, the order is random and can be customized for the recipient or region. The Hours of the Virgin were regarded as the most important, and therefore subject to the most lavish illustration. The Très Riches Heures is rare in that it includes several miracles performed before the commencement of the passion (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

Calendar gallery

Fuller descriptions are available at a University of Chicago website.[3]

- January

A New Year's Day feast including Jean de Berry - February

- March

Château de Lusignan - April

Château de Dourdan - May

Hôtel de Nesle, the Duke's Paris residence - September

Château de Saumur - October

Louvre - November

Technique

Vellum

The parchment or vellum used in the 206 folios is fine quality calfskin. All bi-folios are complete rectangles and the edges are unblemished and therefore must have been cut from the centre of skins of sufficient size. The folios measure 30 cm in height by 21.5 cm in width, although the original size was larger as evidenced by several cuts into the miniatures. The tears and natural flaws in the vellum are infrequent and almost go unnoticed (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

Illustrations

The ground colors were moistened with water and thickened with either gum Arabic or tragacanth gum. Approximately ten shades are used besides white and black. The detailed work required extremely small brushes and probably a lens (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969).

Contents

Summarize

Perspective

The contents of the book are typical of those of a book of hours, though the quantity of illumination is extremely unusual.

- The Calendar: Folios 1–13

- A generalized calendar (not specific to any year) of church feasts and saints' days, often illuminated with representations of the Labours of the Months, is a usual part of a book of hours, but the illustrations of the months in the Très Riches Heures are exceptional and innovative in their size, and the best known element of the decoration of the manuscript.[27] Up to this point any scenes of the labours had been smaller images on the same page as the calendar text,[25] though later 15th-century calendars often adopted the Limbourg's innovation of a full-page miniature, though most had smaller pages than here. They were also unprecedented in mostly showing one of the duke's castles in the background. They are filled with details of the delights and labors of the months, from the Duke's court to his peasants, a counterpart to the prayers of the hours.[28] Each illustration is surmounted with its appropriate hemisphere showing a solar chariot, the signs and degrees of the zodiac, and numbering the days of the month and the martyrological letters for the ecclesiastic lunar calendar. Each month of the calendar is allotted an opening of two pages, on the righthand page the calendar listing notable feast days and on the left the miniature. January is the largest miniature in the calendar and includes the Duke of Berry at a New Year’s Day feast (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969).

- Several of the miniatures depict the Duke, fields or castles he owned, and places he visited. This shows the personal function of the book of hours, as it is customized to suit the patron (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

- The September miniature was almost certainly painted in two phases: first, the upper section with the sky and château was painted in the middle of the fifteenth century, around 1438–1442, in the time of René d’Anjou and Yolande d’Aragon; then the lower scene of grape-picking was completed by Jean Colombe from a sketch left by his predecessor. In general, artists started with the background, then painted in the characters before finishing with their faces.

- In the foreground, it is grape-picking time. The woman in a white and red apron looks pregnant. Other young peasants are picking the purple bunches, while one of them is tasting the grapes. A further character holding a basket is walking towards a mule which is carrying two panniers. The grapes are being loaded either into the mules' panniers or into the vats on the cart pulled by two oxen.

- In the background stands the Château de Saumur with its chimneys and weathervanes decorated with golden fleurs-de-lys. It was built by Louis II d'Anjou then given to his wife Yolande d’Aragon, the mother of King René and mother-in-law of Charles VII, over whom she had a considerable sway. The presence of this château can be explained by the important role played by Yolande in the early years of the reign of Charles VII and by how much the king enjoyed staying there. On the left, behind the enceinte, stands a clock-tower, the chimneys of the kitchens and a gate leading to a drawbridge. A horse is coming out and a woman with a basket on her head is on her way in.

- In front of the château, between the vines and the moat can be seen a tilting ground surrounded by palisades, where tournaments were held.

- The architectural design of the château draws the gaze up towards the dreamily poetic volutes. The towers conceal their protective nature beneath festive trappings, redolent of fabulous adventures in the forests of Arthurian legends and suggestive of the presence of God in His creation. As François Cali put it: "These extravagant towers are a dream landscape with constellations of canopies, pinnacles, gables and arrows, with their crockets fluttering against the light."

- In the middle of the grape pickers, a character is showing his behind. This intentionally grotesque touch contrasts with the extraordinary elegance of the château. Jean Colombe's peasants lack the dignity they have in the other miniatures.

- Anatomical Zodiac Man: Folio 14

- The Anatomical Zodiac Man concludes the calendar. The twelve signs of the zodiac appear over the corresponding anatomical regions. It contains Berry's coat of arms of three fleurs-de-lis on a blue background. Such an image appears in no other book of hours, but astrology was one of Berry's interests, and several works on the subject were in Berry's library.[29] The two figures are sometimes regarded as male and (looking out at the viewer) female, but Pognon finds both "strangely hermaphrodite", and intentionally so.[30]

- Readings from the Gospels: Folios 17–19

- Prayers to the Virgin: Folios 22–25

- Fall of Man: Folio 25

- This part is represented in four stages within the same miniature. The Fall of Man is thought to have been by Jean de Limbourg and was to belong to a series of miniatures not originally intended for the Très Riches Heures.

- Hours of the Virgin Matins: Folios 26–60

- Illustrated with a cycle of the Life of the Virgin, with the page showing the Rest on the Flight to Egypt by Jean Colombe.[31]

- Psalms: Folio 61–63

- The illustrations for the psalms employ a literal interpretation of the text that is rare for the late medieval period (Manion 1995).

- The Penitential Psalms: Folio 64–71

- This section begins with the "Fall of the Angels", which bears a lot of similarity to a panel painting by a Sienese painter dating from 1340 to 1348, now at the Louvre (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969). The Limbourgs may have known this work. This miniature has been identified as not originally intended for the Très Riches Heures. The final opening has a double-page image of the Procession of Saint Gregory that surrounds the text columns, with depictions of the skyline of Rome.[32]

- Hours of the Cross: Folios 75–78

- In this section Christ is depicted as the Man of Sorrows, exhibiting wounds and surrounded by instruments of the passion. This is a common iconographic type in fourteenth-century manuscripts (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

- Hours of the Holy Ghost: Folios 79–81

- Office of the Dead: Folios 82–107

- Colombe painted all the miniatures of this section, other than “Hell”, which was painted by a Limbourg brother. “Hell” is based on a description from a thirteenth-century Irish monk Tundal (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). This miniature may not have been originally intended for the manuscript. Meiss and subsequent writers have argued that the full-page miniatures that codicological data show were inserted on single leaves were not originally designed for the Très Riches Heures (including the Anatomical Man, folio 14v; The Fall, folio 25r; the Meeting of the Magi, folio 51v; the Adoration of the Magi, folio 52r; the Presentation, folio 54v; the Fall of the Rebel Angels, folio 64v; Hell, folio 108r; the Map of Rome, folio 141v). Margaret Manion, however, has suggested that, "although the subjects are handled in an innovative manner, they fit within the context of the prayerbook and could well have been part of a developing collaborative plan."[22]

- The funeral image shows a reputed incident at the funeral of Raymond Diocres, a famous Parisian preacher, when in the middle of his Requiem Mass he was said to have lifted up his coffin lid, and announced to the congregation "I have been condemned to the just judgement of God".[33]

- Short Weekday Offices: Folios 109–140

- The Presentation of the Virgin takes place in front of Bourges Cathedral, in Berry's ducal capital (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969).

- Plan of Rome: Folio 141

- Hour of the Passion: Folio 142–157

- Masses for the Liturgical Year: Folios 158–204

- Folio 201 depicts the martyrdom of Andrew the Apostle. The Duke of Berry was born on Saint Andrew's Day, 1340; consequently this miniature was of great importance to him (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988).

Stylistic analysis

Summarize

Perspective

The Limbourg brothers had artistic freedom but worked within a framework of the religious didactic manuscript. Several artistic innovations by the Limbourg brothers can be noticed in the Très Riches Heures. In the October miniature, the study of light was momentous for Western painting (Cazelles and Rathofer 1988). People were shown reflected in the water, the earliest representation of this type of reflection known thus far. Miniature scenes had new informality, with no strong framing forms at the edges. This allowed for continuity beyond the frame of view to be vividly defined. The Limbourgs developed a more naturalistic mode of representation and developed portraiture of people and surroundings. Religious figures do not inhabit free open space and courtiers are framed by vegetation. This is reminiscent of a more classical representation (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969). Some conventions used by the Limbourgs, such as a diaper background or the portrayal of night, were influenced by artists such as Taddeo Gaddi. These conventions were transformed completely into the artist's unique interpretation (Longnon, Cazelles and Meiss 1969).

Manion offers a stylistic analysis of the psalter specifically. The psalters offer a systematic program of illuminations corresponding to the individual psalms. These images are linked together, but are not in the numerical order of the psalter. This emphasizes the idea of the abbreviated psalter, where each psalm is illustrated once (Manion 1995). The miniatures are not modeled on any specific visual or literary precedence when compared with other fourteenth century psalters. The manuscript offers a literal interpretation of the words and lacks a selection of more personal prayers. This emphasizes the didactic use of the book of hours (Manion 1995).

Restoration and exhibition

In 2023, a process of restoring the manuscript was launched with the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France. A preliminary study was carried out using ultraviolet, infrared and raking light photographs, as well as hyperspectral and microscopic imaging, in order to analyze the condition of the book but also to provide information on the stages of its creation. These initial analyses made it possible to note the poor condition of the 18th century binding. This is why the first notebooks will be unbound in order to proceed with their restoration.

This undertaking will make it possible to present these notebooks flat for the first time, and in particular the calendar folios, at a major exhibition in 2025 at the Château de Chantilly, also bringing together the other books of hours of the Duke of Berry.[34][35][36]

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.